Authors’ note: CAP uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.”

Introduction and summary

The United States is a contradiction. Its founding principles embrace the ideals of freedom and equality, but it is a nation built on the systematic exclusion and suppression of communities of color. From the start, so many of this country’s laws and public policies, which should serve as the scaffolding that guides progress, were instead designed explicitly to prevent people of color from fully participating. Moreover, these legal constructs are not some relic of antebellum or Jim Crow past but rather remain part of the fabric of American policymaking.

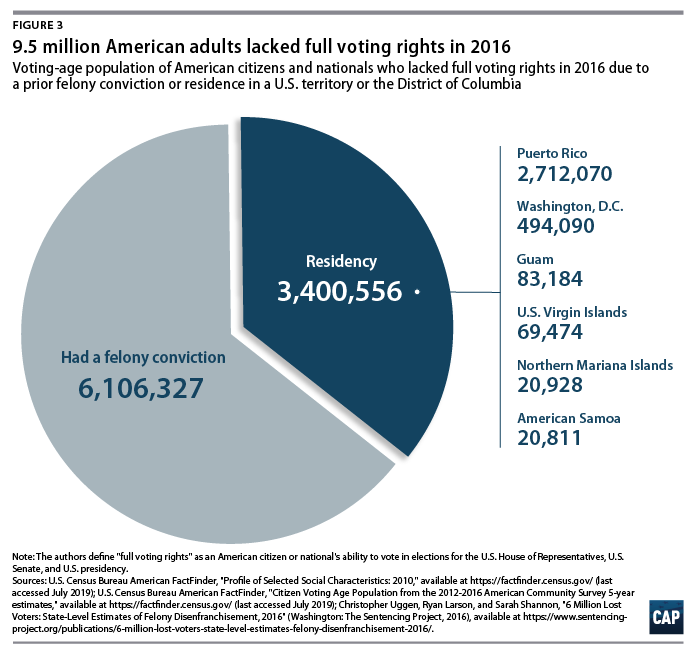

Over the centuries, even as the nation struggled to prohibit the most repugnant forms of exclusion and suppression, it neglected to uproot entrenched structural racism. The inevitable result is an American democracy that is distorted in ways that concentrate power and influence. For example, according to a new Center for American Progress analysis, in 2016, 9.5 million American adults—most of whom were people of color—lacked full voting rights.1

The inability to fully participate in the democratic process translates into a lack of political power—the power to elect candidates with shared values and the power to enact public policy priorities. As a result, people of color, especially Black people, continue to endure exclusion and discrimination in the electoral process, more than 150 years after the abolition of slavery.

This report examines how lawmakers continue to protect discriminatory policies and enact new flawed ones that preserve barriers to voting for people of color. Promoting full participation, therefore, will require intentional public policy efforts to dismantle long-standing barriers and protect the right to vote for all Americans.

Voting and citizenship were largely denied to people of color until 1870

The very first law codifying naturalization in the United States restricted national citizenship to “free white [people] … of good character.”2 While free Black men were at times permitted to vote in some states, enslaved Black people, who constituted more than 85 percent of the nation’s Black population between 1790 and 1860, were unable to vote anywhere in the United States.3 Even in states such as Pennsylvania, where Quakers preached racial tolerance, free African Americans who were legally permitted to vote rarely exercised this right for fear of retribution.4 In 1857, the infamous U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford ruled that no Black person could become a citizen of the United States and thus had no protections to exercise their right to vote.5 By 1865, virtually all white men were permitted to vote in presidential elections, whereas Black men were permitted to vote in just six states.6

In the wake of the Civil War, the United States ratified the 14th and 15th amendments—granting citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the country and prohibiting disenfranchisement based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude.7 The nation also adopted three bills called the Enforcement Acts between 1870 and 1871 that criminalized voter suppression and provided federal oversight in elections.8 These laws broke the back of the first iteration of the Ku Klux Klan and led to hundreds of arrests, indictments, and convictions for those who sought to interfere with Black citizens’ right to vote.9 By 1877—the end of the 12-year period known as Reconstruction—at least 1,510 Black Americans had held elected office on every level of government, from clerks and school superintendents to congressional representatives and U.S. senators.10

The unfulfilled promise of Reconstruction

The end of the Civil War marked an inflection point in U.S. history. The destruction of slavery as a legal institution and the passage of the 14th and 15th amendments promised to usher in a new age of American freedom and democracy. With the support of the U.S. Army and the Freedmen’s Bureau, millions of newly freed African Americans gained access to property ownership, education, and political participation for the first time. The federal government and thousands of volunteers reconstructed the Southern economy, building schools, banks, and hospitals for liberated Black families, and helped protect these families from white nationalist terrorism.11 For a time, federal officials even helped implement Special Field Order No. 15, which mandated the redistribution of roughly 400,000 acres of land confiscated from Confederate planters to newly freed Black families in 40-acre segments.

But lawmakers’ commitment to protecting the constitutional and human rights of Black citizens did not last. Widespread support for Reconstruction faded by the 1870s, and the election of President Rutherford B. Hayes signaled the impending end of the era. The death of Reconstruction fueled resurgence of white nationalist violence, occupational segregation, and racial discrimination designed to trap Black Americans in a semipermanent status of second-class citizenship. The cornerstone of these efforts was the systematic disenfranchisement and suppression of Black voters.

Lawmakers continued to exclude and suppress Americans of color even after the 14th and 15th amendments

Reconstruction offered people of color a glimpse at what American democracy could be. But the visionary moment soon passed and was replaced by nearly a century of brutal suppression and disenfranchisement. Even as the nation became more diverse, and increased attention was given to expanding voting rights, the systematic exclusion of people of color from electoral participation helped ensure that the nation’s democratic institutions and policies would remain racially homogenous.

After Reconstruction, white nationalists waged a campaign of terror to suppress Black voters and seize control of Southern state legislatures

In 1877, the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops from former Confederate states marked the death of Reconstruction and the birth of the Jim Crow era.12 In subsequent decades, Southern states would adopt numerous measures to codify the exclusion and suppression of Black people. Many states simultaneously criminalized low-income Black residents by making vagrancy illegal and prohibited people with convictions from voting.13 While the 13th Amendment prohibited slavery, it also provided an exception for crime. The exception permitted convict leasing, a system that allowed Southern states to lease prisoners for free labor. This set the stage for many states to pass laws, known as “Black Codes,” which only applied to Black people. Once they were convicted under these laws, Black people were leased out to do various jobs.14

During this time period, states also adopted poll taxes and English literacy tests for voting, which required Americans to pay a fee and answer a sometimes endless series of challenging and confusing civics and citizenship questions in order to vote.15 White residents—even those who were low income and illiterate—were conveniently exempted from literacy tests thanks to “grandfather clauses,” which allowed anyone who was eligible to vote prior to the 15th Amendment, along with their descendants, to vote in elections.16 These and other Jim Crow laws made it virtually impossible for otherwise eligible Black citizens to participate in Southern elections.17

The systematic exclusion and suppression of voters of color during this period was not limited to Southern states

In the West, U.S. states routinely adopted measures to undermine democratic participation among communities of color. Oregon, for instance, entered the Union prior to the Civil War with a constitution that explicitly disenfranchised Black and Chinese people.18 After the war, the state’s lawmakers rejected the 15th Amendment and went on to deny suffrage to most people of color until the mid-20th century.19 In fact, Oregon did not ratify the 15th Amendment until 1959—almost 90 years after federal certification.20

On the federal level, the progress made during Reconstruction was followed by decades of policy decisions that limited or completely restricted suffrage for people of color. For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act explicitly prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming American citizens.21 During this period, the United States also acquired multiple overseas territories, such as Puerto Rico and Guam, but denied full suffrage to the territories’ predominantly nonwhite residents.22 While the Chinese Exclusion Act would ultimately be repealed in 1943, 3.4 million otherwise eligible Americans living in U.S. territories—namely Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa—continue to lack full voting rights to this day.23

The civil rights movement dismantled many obstacles to electoral participation

In 1954, Black activists launched the American civil rights movement to ensure that all Americans, regardless of race, could exercise the rights and protections guaranteed to them in the U.S. Constitution.24 Movement leaders and participants risked life and limb in a decades-long struggle against discrimination, segregation, and voter suppression.25 Through nonviolent protest, civil disobedience, litigation, education, and determination, they succeeded in dismantling many of the institutions that had oppressed people of color since the end of Reconstruction.26 Among the many landmark legislative victories of the civil rights movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) and its subsequent amendments ushered in a new era of democratic participation.

The VRA provided the federal government and civil rights leaders with the authority and the tools needed to break the grip of Jim Crow and ensure that all Americans could exercise the fundamental right to vote. Among other things, the VRA prohibited any practice or procedure that denied or limited a citizen’s right to vote because of their race, color, or membership to a language minority group.27 One of the most critical provision was Section 5, which prevented jurisdictions with an established history of discriminatory anti-minority election practices from enacting unfair voting policies.28 Under Section 5, these jurisdictions were required to seek permission from the U.S. Department of Justice or a federal court before making any changes to election processes or their voting procedures.29

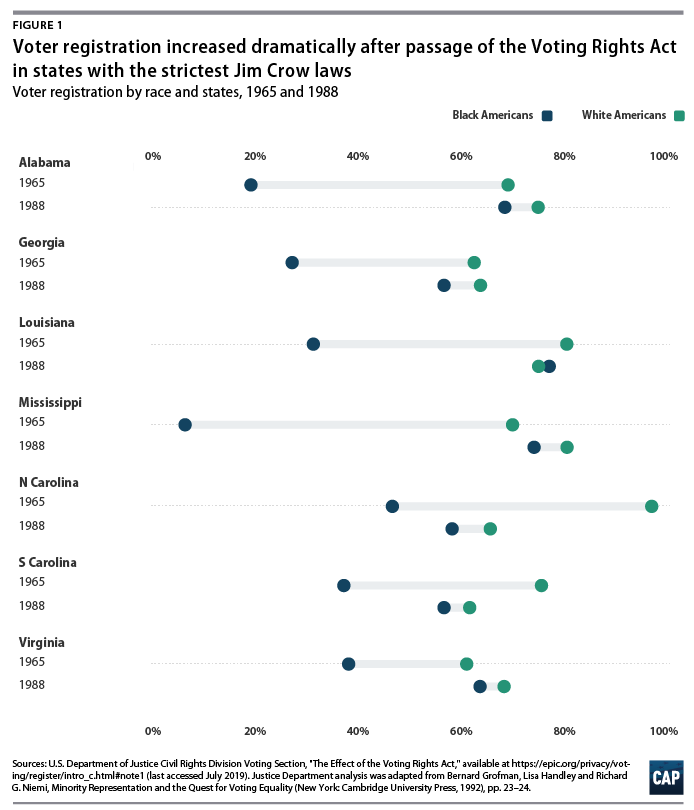

The VRA expanded access to the ballot box for hundreds of thousands of voters of color. From 1965 through 1988 alone, the number of Black citizens registered to vote in places such as Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana more than doubled.30 (Figure 1) Mississippi experienced a more than tenfold increase in Black voter registration during this period.31 Increased access to voting translated into more Black legislators across all levels of government. In just one decade—1970 to 1980—the total number of Black elected officials in the United States tripled, from just 1,469 to 4,912.32

The VRA’s unprecedented expansion in voting rights was bolstered by subsequent amendments. The law’s 1975 and 1992 amendments, for instance, protected language minorities and required certain jurisdictions to provide translated voting materials to prevent discrimination against Americans with limited English proficiency (LEP).33 Today, jurisdictions are covered if, among other things, the LEP population is greater than 10,000 or constitutes more than 5 percent of all voting-age citizens.34 This helped expand access to the ballot box for countless Asian American, Latinx, and Native American voters with LEP.35 These amendments were an important step forward along the path to full participation in American democracy.

But the VRA did not fully succeed in ripping out the roots of structural racism in American democracy. Across the country, federal and state lawmakers continued to attempt to curtail voting rights among communities of color. They also began developing innovative new strategies for voter suppression.36 For instance, in 2011 and 2012 alone, lawmakers in California, Florida, Illinois Michigan, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, and South Carolina introduced bills that would make it more difficult to register to vote by curbing registration drives.37 American citizens with prior felony convictions and those who live in Washington, D.C., and the U.S. territories also remained largely excluded from democratic participation, even after the passage of the VRA. Despite these limitations, the VRA remains one of the biggest voting rights victories in American history due to its unprecedented expansion of the franchise and elimination of many structural barriers to democracy.

The United States has experienced a resurgence of voter suppression

In 2012, the national voter turnout rate among Black citizens exceeded that of white citizens for the first time in American history.38 But this was quickly followed by two devastating U.S. Supreme Court rulings that eliminated core voting rights protections and threatened to undo decades of progress toward a vibrant democracy.39 These rulings, combined with the continued existence of decades-old voter suppression and disenfranchisement policies, threaten the fundamental right to vote for millions of Americans.

The U.S. Supreme Court gave states the green light to suppress voters of color

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act by declaring the formula used to determine covered jurisdictions unconstitutional.40 Without a coverage formula, Section 5 is essentially unenforceable, meaning that states with a history of overt white supremacy and voter suppression can once again manipulate their voting policies and procedures without first seeking approval from federal officials.

The response to Shelby in many formerly covered jurisdictions was swift and predictable. In North Carolina, for instance, lawmakers rushed to impose a strict voter ID requirement. According to the state NAACP, which filed suit against the ID requirement, the law permitted “only those types of photo ID disproportionately held by whites and excluded those disproportionately held by African Americans.”41 The law threatened to suppress thousands of Black voters and was eliminated only after a federal court ruled that North Carolina sought to “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”42 But North Carolina was not alone. Multiple formerly covered jurisdictions have used their new freedoms to enact strict voter ID laws, close polling places, and limit access to early voting.43

The wave of voter suppression laws enacted after Shelby v. Holder was not restricted to formerly covered jurisdictions. In North Dakota, for instance, lawmakers adopted a strict voter ID law targeting Native American voters. The law—which was in place for the 2018 midterm elections—contained a provision requiring citizens to present an ID with a valid residential street address in order to vote.44 But many Native American voters living on reservations had no residential street address to put on an ID card.45 In fact, almost 1 in 5 otherwise eligible Native American voters was affected by this law.46 In response, the Native American Rights Fund, four tribes, and multiple community organizations rushed to coordinate the provision of tribal documents containing residential street addresses so that every eligible citizen would be able to cast a ballot on election day.47 Today, in this new era of voter suppression, states are adapting old tactics to make it more difficult for people of color to vote.

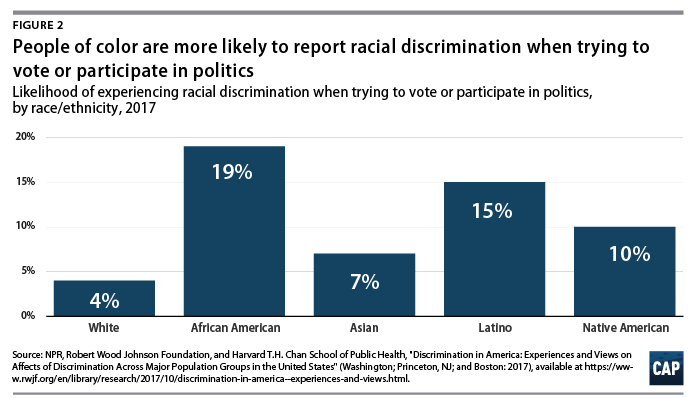

In 2017 alone, Native Americans, Latinos, and African Americans were two, three, and four times, respectively, more likely than their white counterparts to report experiencing racial discrimination when trying to vote or participate in politics.48 (see Figure 2)

Millions of Americans of color remain structurally excluded from American democracy

While the country’s progress is indisputable, people of color still continue to lack full voting rights in America.

Felony disenfranchisement was one of the most powerful tools for denying the vote to Black citizens during the Jim Crow era. Despite the many achievements of the VRA, this discriminatory policy has been allowed to persist and expand across the country for decades. Notably, the war on drugs targeted people of color for arrest and incarceration, magnifying the effects of felony disenfranchisement nationwide.49 For democracy to work, citizens—including those who have made past mistakes, paid their debt to society, and now lead productive lives—must be allowed to vote and fully participate in the electoral process. But in 2016 alone, 6.1 million Americans, most of whom are people of color, were unable to cast their ballots on election day due to a felony conviction.50

The denial of full suffrage for residents of Washington, D.C., and the U.S. territories has also gone largely unaddressed in recent history. Each election year, millions of American service members, diplomats, and expatriates living abroad vote in their home states using absentee ballots.51 But American adults living in Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa continue to lack full voting rights. Washington residents serve in the military and pay federal taxes, but they have just a single presidential electoral vote and no voting power on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives or U.S. Senate.52 Americans in the territories have even less representation: They are not afforded presidential electoral votes. In 2016, 3.4 million Americans—most of whom are people of color—were unable to cast a ballot due to their residency in Washington, D.C., or a U.S. territory.53

Felony disenfranchisement and the denial of suffrage to Washington, D.C., residents and Americans in the U.S. territories is the result of lawmakers’ failure to fully uproot entrenched structural racism. Together, these policies affected 9.5 million Americans in 2016—more than the total number of eligible voters in Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, Rhode Island, Montana, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Maine, and Idaho combined.54 Collectively, these 12 states—most of which are predominantly white—have 17 voting members in the House of Representatives, 24 senators, and 41 electoral college votes. Citizens with prior felony convictions and those residing in Washington, D.C., or the territories are no less American. But, as a result of discriminatory policies, they have far less political power to elect candidates with shared values and policy priorities in America’s democracy. Thus, these predominantly nonwhite Americans continue to endure exclusion, discrimination, and exploitation more than 150 years after the abolition of slavery.

Enduring and emerging threats to voting rights are a constant reminder of how far America needs to go to ensure full access to American democracy

In recent years, policymakers have tested the limits of how far they can go to prevent people of color from voting. Discriminatory voter purges, modern-day poll taxes, and the revocation of citizenship threaten to upend American democracy.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court again gave voter suppression its stamp of approval when it ruled in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute that states were permitted to throw eligible Americans off their voter rolls—also known as purging—just because they decided to skip some elections.55 The ruling upheld Ohio’s decision to purge 846,000 disproportionately Black voters from its rolls for infrequent voting over a six-year period.56 The court’s Husted decision opens the door to remove millions of Americans of color on voter rolls.

The 24th Amendment banned poll taxes from being used to prevent citizens from voting.57 But earlier this year, Florida enacted a modern-day poll tax that disproportionately targets the state’s Black residents.58 The previous year, Florida voters had cast their ballots in favor of amending the state’s constitution to restore voting rights to U.S. citizens with prior felony convictions.59 This change would return suffrage to 1.4 million Floridians, including 1 in 5 Black residents.60 However, Republican legislators in Tallahassee, led by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), circumvented voters’ wishes by imposing new financial restrictions—such as fees unrelated to citizens’ sentences—for individuals with prior felony convictions to vote.61 These restrictions are eerily similar to the poll tax system pioneered by the state 130 years earlier.62 Like those of the Jim Crow era, modern-day poll taxes target Black residents and present a barrier to voting.

The 14th Amendment guarantees American citizenship for all people born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.63 But just last year—150 years after the ratification of the 14th Amendment—President Donald Trump announced his intention to craft an executive order revoking the citizenship of any American with an undocumented parent.64 This announcement was unsurprising: President Trump has spent much of his first term in office attempting to prohibit Muslims from entering the United States; separating children of color from their parents and placing them in cages along the southern border; and trying to undermine the asylum process for women of color fleeing domestic violence.65 While such a threat is racist, xenophobic, and constitutionally dubious, it stokes fear in millions of Americans of color. These recent examples serve as a critical reminder that some of the most powerful lawmakers in the so-called land of the free remain committed to limiting full access to American democracy.

Conclusion

A successful democracy requires the full participation of its citizens. However, despite legal and policy advancements that have extended the right to vote, the United States continues to conjure the ghosts of an ugly past by employing new voter suppression tactics that target people of color. Remaining vigilant against these efforts and rejecting any and all remnants recalling the racist past is not an option.

To that end, federal lawmakers should fully restore Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Furthermore, they should enact new laws to prevent foreign powers from targeting voters of color for disinformation campaigns.

State lawmakers should immediately repeal any and all felony disenfranchisement, strict voter ID, modern-day poll tax, and discriminatory voter purge policies. They should also pass new laws to prevent unnecessary poll closures and ensure that all Americans, regardless of English proficiency, can participate in elections.

These measures are not a panacea, nor are they exhaustive, but instead represent critical steps in ensuring that all Americans—no matter their race, color, or creed—can fully participate in U.S. democracy.

About the authors

Danyelle Solomon is the vice president of Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Connor Maxwell is a policy analyst for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center.

Abril Castro is a research assistant for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center.

Methodology

The authors used several sources to generate estimates for the total number of American citizens and nationals who lacked full voting rights in 2016. First, the authors defined “full voting rights” as American citizens’ or nationals’ ability to cast ballots in U.S. House, U.S. Senate, and presidential elections. To determine the citizen voting-age population (CVAP) in Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, the authors utilized the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2012–2016 American Community Survey’s (ACS) five-year estimates. The ACS does not produce reliable CVAP estimates for Guam, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, or the Northern Mariana Islands. Therefore, the authors utilized demographic profiles from the 2010 decennial census. CVAP estimates were calculated by applying estimates for the percentage of American citizens and nationals in each of these territories to the territories’ voting-age population. The authors recognize that precision is limited by the possibility that citizenship and nationality may not be evenly distributed across all age groups in these territories.

Finally, the total number of Americans disenfranchised due to felony convictions comes from the Sentencing Project report “6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016.”66