Countervailing forces continue to hold back the recovery, particularly the ugly mess of “management by crisis” that characterizes current federal fiscal policy. Two separate issues stand out:

Congress is also unable to do its job because a right-wing minority wants to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which was passed by a majority of Congress and upheld by the Supreme Court. Congress is thus unable to pass a budget as the conservative majority in the House bends to the will of this radical minority, and it is unwilling to pay the bills it has already racked up by unconditionally raising the federal debt ceiling, which the federal government will reach some time in October.

The result is tremendous uncertainty over whether the federal government will stay open beyond September 30—the end of the federal government’s fiscal year—which bills will be paid when, which programs will continue in the future, and which contracts will be extended. Households that rely on government checks, such as Social Security and Medicare recipients, may postpone their spending decisions. Businesses counting on government contracts to build roads, schools, or bridges may delay hiring and investing in new equipment. And financial markets could extract a risk premium in the form of higher interest rates on government debt if this uncertainty continues. Other interest rates on mortgages and business loans, for instance, could follow suit since all interest rates are tied to the interest rates on government debt. Higher interest rates would lead to less consumption and less investments, slowing the recovery further.

Congress appears to have lost sight of what is important to millions of Americans: more good, well-paying jobs that allow employees to take care of their families, stay out of debt, and save for their future. Congress needs to pass a budget that enhances rather than hurts growth. And it needs to own up to its past spending decisions and raise the debt ceiling without conditions and delay. American families have suffered enough during and after the Great Recession to see their economic fortunes become the pawns in a political game of chicken.

1. The economy continues to grow slowly. Gross domestic product, or GDP, increased in the second quarter of 2013 at an inflation-adjusted annual rate of 2.5 percent. Domestic consumption increased by an annual rate of 1.8 percent, housing spending substantially grew by 12.9 percent, and business investment accelerated by 4.4 percent. Exports increased by 8.6 percent in the first quarter, but government spending shrank again by 0.9 percent, slowing overall growth.

The U.S. economy was 9.2 percent larger in June 2013 than in June 2009 (in inflation-adjusted terms), when the recovery started. On average, however, the economy has expanded by 19.1 percent—more than twice as fast—during the first four years of a recovery, in recoveries that lasted at least four years. Fiscal austerity abroad and at home is hurting economic growth. Policy solutions should therefore aim to ease the strain of U.S. fiscal austerity on the economy and replace across-the-board spending cuts with a fiscal policy approach that can actually enhance rather than slow economic growth, while also reducing long-term deficits.

2. The moderate labor-market recovery continues in its fourth year. There were 5.6 million more jobs in June 2013 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery officially started, and the private sector added 6.3 million jobs during this period. The loss of more than 678,000 state and local government jobs explains the difference between the net gain of all jobs and the private-sector gain in this period. Budget cuts reduced the number of teachers, bus drivers, firefighters, and police officers, among others. Job creation should be a top policy priority since private-sector job growth is still too weak to quickly overcome other job losses and rapidly lower the unemployment rate. A reorientation of tax and spending policies to strengthen economic growth rather than a blind obsession with deficit reduction at all costs could create millions of jobs that America’s middle class desperately needs.

3. Some communities continue to struggle disproportionately from unemployment. The unemployment rate stood at 7.3 percent in June 2013. The African American unemployment rate was 13 percent in June 2013, the Hispanic unemployment rate was 9.3 percent, and the white unemployment rate was 6.4 percent. Meanwhile, youth unemployment stood at 22.7 percent. The unemployment rate for people without a high school diploma ticked up to 11.3 percent, compared to 7.6 percent for those with a high school degree, 6.1 percent for those with some college education, and 3.5 percent for those with a college degree. Population groups with higher unemployment rates have struggled disproportionately more amid the weak labor market than white workers, older workers, and workers with more education. Policymakers should heed the recommendations in All-In Nation—a new book from the Center for American Progress and PolicyLink—on building a strong and diverse workforce that draws from all communities.

4. The rich continue to pull away from most Americans. Incomes of households in the 95th percentile—those with incomes of $191,000 in 2012, the most recent year for which data are available—were more than nine times the incomes of households in the 20th percentile, whose incomes were $20,599. This is the largest gap between the top 5 percent and the bottom 20 percent of households since the U.S. Census Bureau started keeping record in 1967. Median inflation-adjusted household income stood at $51,017 in 2012, its lowest level in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1995. And the poverty rate remains high, at 15 percent in 2012, as the economic slump continues to take a massive toll on the most vulnerable citizens.

5. Poverty stays high. The poverty rate remained flat at 15 percent in 2012, the most recent year for which data are available. The African American poverty rate was 27.2 percent, the Hispanic poverty rate was 25.6 percent, and the white rate was 9.7 percent. The poverty rate for children under the age of 18 stood at 21.8 percent. More than one-third of African American children—37.9 percent—lived in poverty in 2012, compared to 33.8 percent of Hispanic children and 12.3 percent of white children. The prolonged economic slump, following an exceptionally weak labor market before the crisis, has taken a massive toll on our country’s most vulnerable citizens.

6. Employer-sponsored benefits disappear. The share of people with employer-sponsored health insurance dropped from 59.8 percent in 2007 to 54.9 percent in 2012, the most recent year for which data are available. The share of private-sector workers who participated in a retirement plan at work fell to 39.2 percent in 2011, down from 42 percent in 2007. Families now have less economic security than in the past due to fewer employment-based benefits, which requires that they have more private savings to make up the difference.

7. Family wealth losses still linger. In June 2013 total family wealth was down $1.5 trillion (in 2013 dollars) from March 2007, its previous peak. Homeowners on average own only 49.8 percent of their homes—compared to the long-term average of 61 percent before the Great Recession—with the rest owed to banks. Homeowners’ massive debt slows household-spending growth, as households still have little collateral for banks to loosen their lending standards and households spend less than they otherwise would on new homes and other big-ticket items.

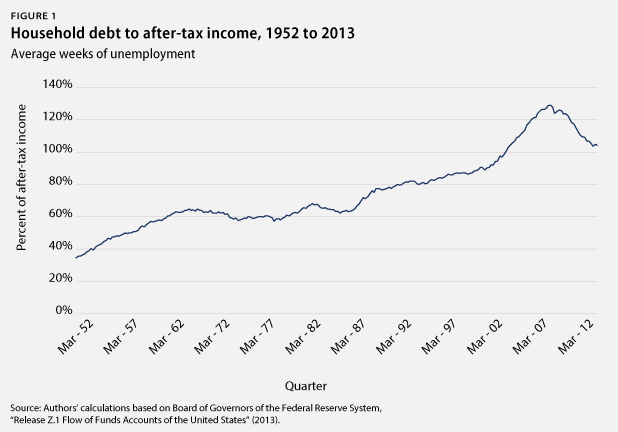

8. Household debt is still high. Household debt equaled 104.3 percent of after-tax income in June 2013, down from a peak of 129.5 percent in December 2007. Household debt has hovered around 105 percent of after-tax income for one year now. That is, the unprecedented deleveraging—debt decline—trend that marked the Great Recession has stopped. A return to debt growth outpacing income growth, which was the case prior to the start of the Great Recession in 2007, from already-high debt levels could eventually slow economic growth again. This would be especially true if interest rates also rise from historically low levels due to a change in the Federal Reserve’s policies and crowd out household spending on other items.

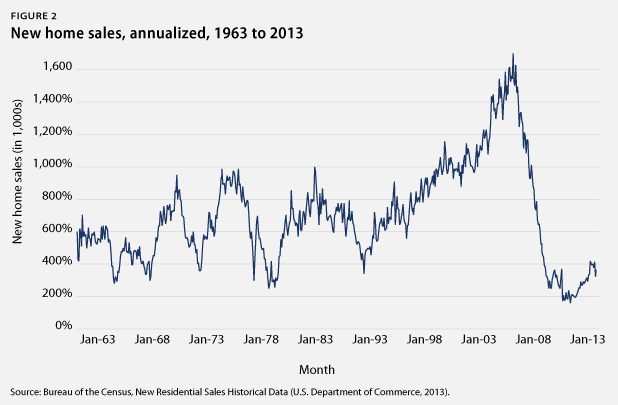

9. The housing market continues to recover from historic lows. New home sales amounted to an annual rate of 421,000 in August 2013—a 12.6 percent increase from the 374,000 homes sold in August 2012 but well below the historical average of 698,000 homes sold before the Great Recession. The median new-home price in August 2013 held steady from one year earlier. Existing-home sales were up by 13.2 percent in August 2013 from one year earlier, and the median price for existing homes was up by 14.7 percent during the same period. Home sales have to go a lot further, given that homeownership in the United States stood at 65 percent in the second quarter of 2013, down from 68.2 percent before the recession. The current homeownership rates are similar to those recorded in 1995, well before the most recent housing bubble started. Though the housing-market recovery started later than the wider economic recovery—and started out at a record low—lately the housing market has been growing rapidly and contributing a much-needed boost to economic progress. As such, there is still plenty of room for the housing market to provide more stimulation to the economy more broadly. The fledgling housing recovery could gain further strength if policymakers support economic growth and job creation at the same time.

10. Corporate profits stay high near pre-crisis peaks. Inflation-adjusted corporate profits were 84.5 percent larger in June 2013 than in June 2009, when the economic recovery started. The after-tax corporate-profit rate—profits to total assets—stood at 3.2 percent in June 2013, nearing the previous peak after-tax profit rate of 3.3 percent that occurred prior to the Great Recession.

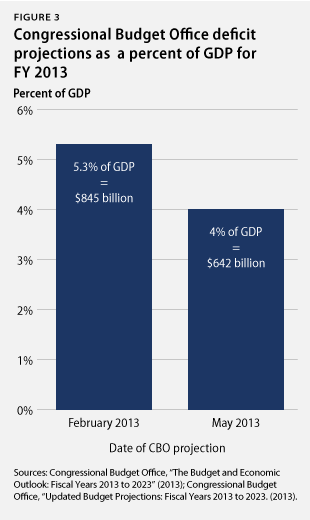

11. The outlook for budget deficits improves. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, estimated in May 2013 that the federal government will have a deficit—the difference between taxes and spending—of 4 percent of GDP for fiscal year 2013, which runs from October 1, 2012, to September 30, 2013. This deficit projection is down from 7 percent in FY 2012. This projected deficit for FY 2013 is better than what CBO predicted in February 2013, when it estimated a deficit of 5.3 percent of GDP for FY 2013. This improvement follows larger-than-expected tax collections, an improving economy, and slower health care inflation, among other factors. The estimated deficit for FY 2013 is much smaller than it was in previous years due to a number of measures that policymakers have already taken to slow spending growth and raise a little more revenue than was expected just last year. The improving fiscal outlook generates breathing room for policymakers to focus their attention on long-term growth and job creation in addition to long-term deficit reduction.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor in the Department of Public Policy and Public Affairs at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Sam Ungar is a Research Assistant at the Center.