Policymakers are already discussing plans to reopen the U.S. economy—even though the COVID-19 pandemic is still ravaging the United States and has killed more than 40,000 people.1 While some of the hardest-hit cities may be flattening the curve, these discussions ignore the many parts of the country that have not even come close to reaching the peak of the outbreak. For example, a large pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, was forced to shut down because of a severe coronavirus outbreak.2 Tribal communities in the Southwest are also beginning to get hit hard.3 While Congress has passed several packages to deal with both the public health crisis and the economic crisis, it is premature to think about an exit strategy before the extent of the pandemic has been realized.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was the third of these packages, providing resources and relief to the U.S. economy as the country combats the COVID-19 pandemic. The package included direct payment assistance to individuals, expanded unemployment insurance, a $500 billion fund to industries, and $350 billion for small businesses. In addition, the package allocated $150 billion to the states for relief as state and local governments face severe budget constraints.

While $150 billion will help states and localities, their needs call for much more resources. One of the major problems resulting from this pandemic is the decimation of state budgets.4 Due to social distancing and shelter-in-place ordinances, sales taxes are going to fall precipitously. States have followed the federal government and pushed their income tax deadlines to the summer, which means the income tax revenue that is normally expected in the spring will not come until the summer or fall.5 In addition, efforts to combat the outbreak and fight the spread of the virus will strain public services. These issues—coupled with the fact that many states face a balanced budget amendment—mean that an economic disaster is brewing across the country. States will have to cut services, furlough workers, or raise taxes when the economy can least afford these cuts. In fact, falling revenues have already forced states to engage in budget cuts.6

The struggles states face will have dire consequences for rural areas. Beyond some funding for rural health care and telemedicine, rural communities were practically left out of the policy debate surrounding all three federal relief packages.7 Supporting rural areas is not something that should be left only to the states; the federal government needs to directly invest in these communities. The spread of the coronavirus is a national challenge, not one that should be left to states by themselves, as the virus does not care where people live.

The coronavirus is already hitting rural America, and existing structural barriers are making the pandemic worse. Rural areas are in need of targeted relief, which has been missing in the previous COVID-19 relief packages. Policymakers must address these omissions by expanding Medicaid in the states that have not yet done so, and the federal government must increase funding to states to support Medicaid. In addition, the lack of a national stay-at-home order is slowing the response, since the virus is spreading in places that have failed to implement these orders.8 Physical distancing is effective at fighting the spread of the coronavirus.9 A national stay-at-home order would take the decision out of the hands of governors who have refused to adhere to the science.10 Policymakers cannot wait to help rural communities because delays in combating this pandemic will lead to an increase in the number of preventable deaths.

The spread of the coronavirus in rural communities

While major metropolitan cities are being hit hard and have the largest outbreaks, COVID-19 has already started to spread in rural communities. Due to the lack of health care infrastructure resulting from hospital closures and a population with a high level of chronic health issues, these communities will be less able to successfully combat the virus.11 Kaiser Health News produced a sobering map showing that the vast majority of rural counties either have no intensive care units in their hospitals or no hospitals at all.12 Yet, the problem is more than just a lack of access to health care facilities. Rural residents generally have to travel long distances to access goods and services such as local food markets and educational institutions. Transportation has always been an issue for rural communities, but it takes on a greater weight during this crisis for seniors and people with disabilities.13

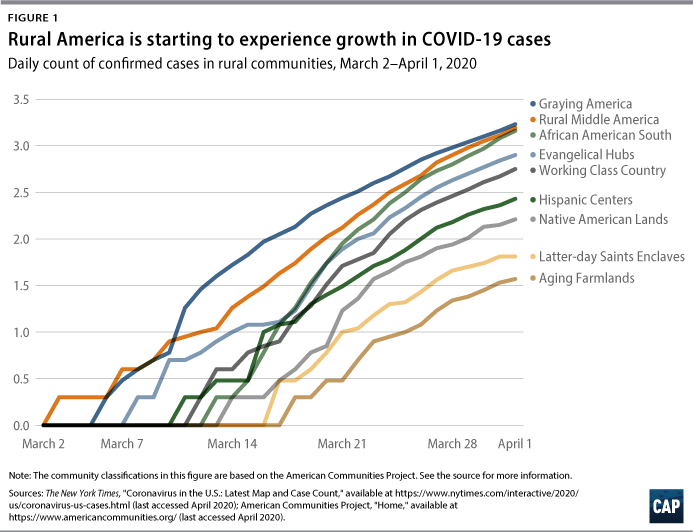

There are concerns that the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 are underreported. The extent of the spread is unknown, since there are likely people who were not tested but who contracted COVID-19 or people who died due to complications from the disease.14 Figure 1 demonstrates the rapid increase of cases that occurred in March 2020.

As seen in Figure 1, Graying America communities are rural areas that have a high prevalence of aging retirees. They are located in recreation-dependent counties predominantly in the western part of the country. These areas have seen a lot of tourism, which has helped boost their economies but has now led to a rise in COVID-19 cases.15 The African American South is a collection of counties synonymous with the so-called Black Belt region of the United States, a series of counties running from the Mississippi Delta, past the Carolinas, and up to Virginia. This area has persistent poverty, low educational attainment, and high uninsured rates.16 These factors make individuals in the region more susceptible to public health crises, and the data now bear this out.17

There were very few reported COVID-19 cases in rural areas during the first two weeks of March. Then, the number of cases started to rise, especially in three rural community categories: Graying America, Rural Middle America, and Evangelical Hubs. However, in the African American South, cases did not begin to rise until mid-March. Cases in this region then proceeded to surpass those in Evangelical Hubs and then caught up to those in Graying America and Rural Middle America by the end of the month. Graying America had its first case on March 6 and, as of April 1, had 1,690 cases. The African American South had its first outbreak on March 10 and, as of April 1, had 1,452 cases. Rural Middle America had its first case on March 2 and, as of April 1, had 1,545 cases. Evangelical Hubs also had their first case on March 6 and, as of April 1, had 802 cases.

Defining urban and rural communities

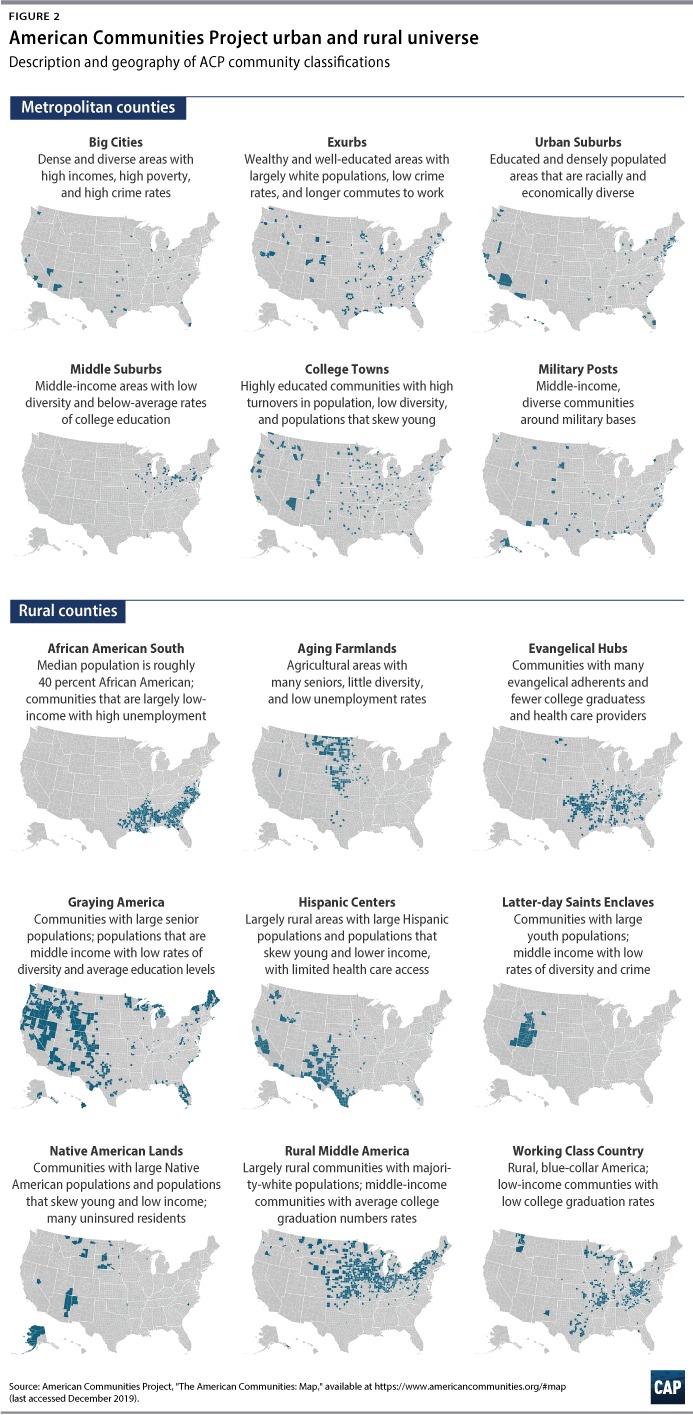

Using a detailed breakdown of rurality, a recent Center for American Progress issue brief outlined what has happened in rural communities since the Great Recession.18 One takeaway was that while rural communities have continued to struggle since the Great Recession, some have seen modest growth. This breakdown of rurality provides a more precise analysis of the labor market dynamics occurring in rural communities. Now, it is possible to provide even further precision on what is happening in urban and rural communities using a new classification system: the American Communities Project (ACP).19 A project from George Washington University, the ACP created a typology of counties that incorporates demographic and socioeconomic data.

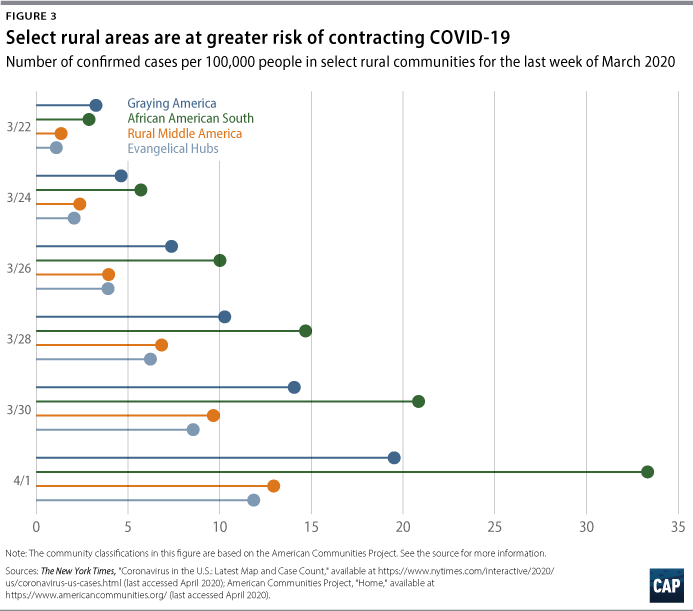

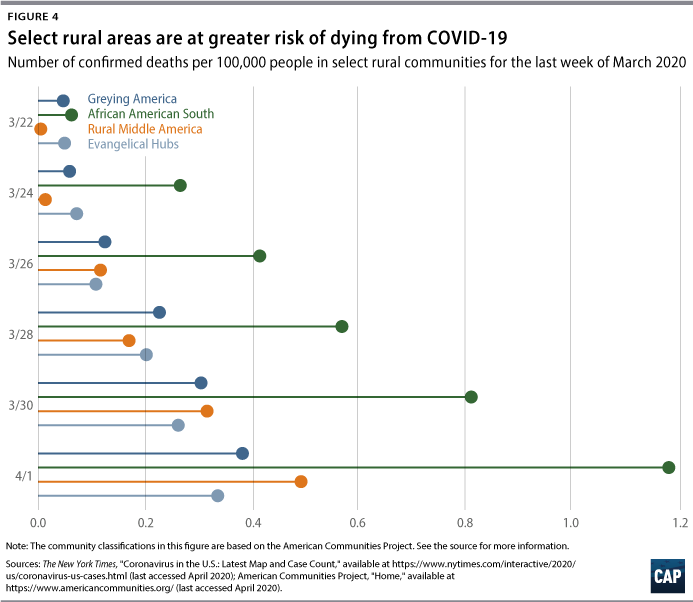

Figures 2 and 3 show that African Americans in rural southern communities are more likely to contract the virus and to have a higher death rate. In fact, while Graying America has more confirmed cases than the African American South, as of April 2, there were more than twice as many deaths—53 compared with 24—in the African American South. A number of these counties are in states that refuse to expand Medicaid, especially those communities in the South such as the African American South and Evangelical Hubs.20 The communities are in states that also have lower public expenditures on programs that support low- to middle-income residents.21 Due to the lack of government resources, these numbers are only going to grow and translate into more preventable deaths. Now that the virus has reached them, these communities will need funds and resources to fight the epidemic.

Even when states get money, some towns are left behind

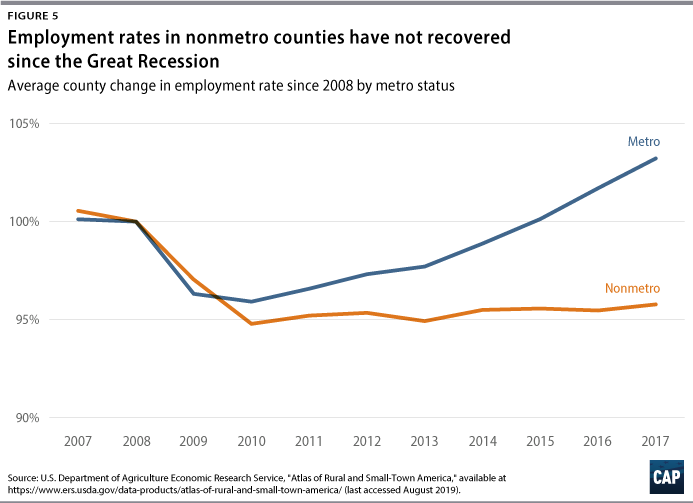

Funding for rural communities comes from a variety of sources, both federal and state. The CARES Act allocates $150 billion to the states and about $30 billion to localities, but this leaves many localities without the help they need. The $30 billion designated to localities will go only to cities with populations of at least 500,000 people. Given the fact that the $150 billion is already not enough for state budgets,22 rural communities are going to be at a disadvantage in accessing these resources. These communities have already been bypassed for needed resources even when they have applied for emergency funding.23 Small towns are already at a disadvantage when competing for grants since large cities have teams dedicated to securing funding. Meanwhile, in small towns, mayors are often responsible for securing grants while also having a day job. This pandemic is only going to exacerbate this inequality. Rural towns have been left behind in past economic recoveries—none more so than after the Great Recession. (see Figure 4)

Policymakers need to find a way to provide resources to rural communities if they want to avoid a repeat of the lackluster recovery from the Great Recession. Rural communities are going to be especially hard hit from this pandemic because of the lack of infrastructure, dwindling health care resources, and an aging population and higher prevalence of people with disabilities—all factors that highlight how these communities are in need of immediate support.24 In addition, some rural localities do not have a large enough tax base to match the level of services needed.

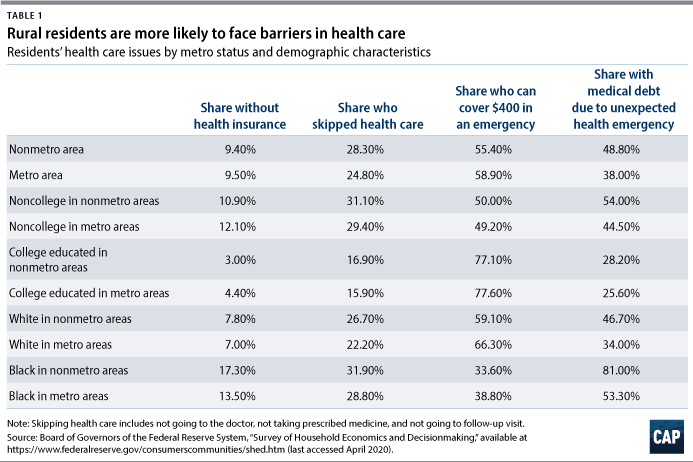

In addition to budget difficulties, many in rural communities will struggle with the public health aspect of this pandemic. People in rural areas are already more likely to skip health care and to have medical debt due to an unexpected health emergency. Rural residents are more likely to not seek medical care until it is too late, partially due to a lack of nearby health facilities.25 They tend to only seek care when health issues become a serious emergency, leading to large medical expenses. These trends are true across race and educational attainment. It is particularly a concern for both African Americans and noncollege-educated individuals in rural communities. (see Table 1)

This troubling reality will make it difficult for these communities to fight the spread of the coronavirus if people do not immediately seek medical help when they experience symptoms. Seeking medical care is difficult because of the many closures of rural hospitals and emergency centers.26 And the lack of Medicaid expansion has been detrimental to many rural communities, particularly in southern states.27 Moreover, the availability of testing for COVID-19 in rural areas has fallen far behind that of urban areas, although steps have been taken to close this gap.28

Preventing the collapse of small-town America is crucial now that policymakers and scholars are recognizing the importance of place-based policies for revitalizing communities and reversing decades of regional divergence.29 Telling rural residents to move to opportunity in urban areas is no longer a viable strategy because urban wage premiums over rural areas no longer exist.30

Policy recommendations

Even though Congress and the Trump administration have put together several packages amounting to more than $3 trillion to help stabilize the economy and combat the coronavirus, there is still more to be done, and policymakers are discussing further measures.31 Additional spending for states and localities—spending that is sizable, flexible, and able to cover programmatic shortfalls—must be a part of a future bill so that these areas can continue to provide necessary services and ensure effective functioning of government.32 Spending for rural areas also needs to be a part of the bill. The following are four recommendations to help rural areas fight this epidemic:

- First, rural areas need help strengthening and expanding their health care infrastructure. The first thing that states can do, if they haven’t already, is expand Medicaid. Medicaid expansion has been responsible for saving thousands of lives and has helped with lowering medical debt—something that has plagued many rural residents, especially African Americans.33 Medicaid expansion would also help with rural hospitals’ financial solvency through lower levels of uncompensated care. In addition, the state attorneys general leading the California v. Texas case must withdraw their participation so that those with health insurance can get and keep the medical help they will need if they get infected.34

- Second, to counteract states’ falling revenues, the federal government must build on earlier COVID-19 response legislation. The second package increased the federal government’s share of Medicaid payments—the Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentages—by 6.2 percentage points for the duration of public health emergencies. Congress must raise the share increase to at least 10 percentage points for both traditional and expansion Medicaid. This aid must be extended for the duration of any future recession—not simply for the current public health emergency. Moreover, this type of relief should also be automatically pegged to increases in state unemployment rates, which will ensure continued aid during future economic downturns.

- Third, policymakers need to implement a national stay-at-home policy to curb the outbreak. Physical distancing can limit the outbreak and, along with massive testing, allow for the suppression of transmission.35 The reluctance of certain states to impose these orders and moves to prematurely lift them provide justification for a national policy.

- Finally, policymakers can create dedicated funding streams for micropolitan areas and small towns with populations below 50,000. These are the areas that have been struggling with rural hospital closures and other infrastructure issues such as the lack of broadband access.36 This will help with the problem of small communities having to compete with larger municipalities for scarce federal and state resources.

Conclusion

Policymakers have pushed three packages through Congress to tackle the coronavirus pandemic. Unfortunately, these packages have failed to provide sufficient resources to support African Americans,37 people with disabilities,38 and state and local governments.39 Rural communities have also been left behind and must be a part of the policy debate. Providing resources to rural areas is one pathway to help the many communities of color and people with disabilities fight back against the coronavirus.40

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.