How much is your car payment? Your mortgage? Your most recent grocery bill?

Most Americans can answer these questions. But most Americans can’t answer how much they pay for their retirement accounts—and that is a big problem.

In April 2015, the U.S. Department of Labor issued an important draft rule that would require financial advisers to act in their clients’ best interests. That’s a huge win for the middle class: The White House estimates that conflicts of interest result in retirement investors losing a combined $17 billion per year.

But we could go even further, potentially saving American families an additional $17 billion per year.* How? By directly providing investors with easy-to-use information through two simple concepts: retirement labels and retirement receipts.

Of any single financial decision that workers can make, few choices have as big an effect on their overall quality of life as how they choose to invest their retirement savings. Yet American investors do not have enough usable information to make an informed decision.

Until 2012, there was no requirement for 401(k) providers to tell investors how much they were paying in fees for their accounts. And unless you are a forensic accountant, you probably have not navigated the multiple pages detailing these expenses and determined how much you are really paying in 401(k) fees.

There is another problem. It is far too easy for most people to underestimate the power of compounding. For example, with existing 401(k) disclosures, investors can see that retirement fund option A costs 0.25 percent per year, or 25 basis points, while option B costs 1 percent per year, or 100 basis points. Current disclosures tell you that if you had $1,000 invested in option A, it would cost $2.50 in fees that year, while option B would cost $10.

But most Americans with 401(k) or IRA balances are not investing $1,000 over a single year. Rather, they are investing tens of thousands of dollars over a period of decades. So the difference in fees between these two scenarios is not really $7.50. Instead, due to compounding interest, it could be almost ten thousand times that difference by the time a worker retires.

Take, for example, a median-wage worker investing 5 percent of his income in a 401(k) starting at age 25 and receiving a 5 percent company match. By the time this worker retires, an annual fee difference of just 0.75 percent could be worth $71,000 according to research by the Center for American Progress. In other words, this worker would have to work three years longer just to cover that excess fee difference.

Simply put: Fees matter. An often-cited 2009 study by Javier Gil-Bazo and Pablo Ruiz-Verdú detailed a “negative relation between funds’ before-fee performance and the fees they charge to investors.” That is to say, higher fees do not necessarily translate to better performance. In fact, that is often not the case.

If policymakers are serious about helping the American middle class, they need to give investors information that they can actually use. That is why CAP previously proposed a retirement label that would provide a more visible, effective disclosure of fund fees to those saving for retirement. This nutrition-style label would be placed on all fund materials—whether online or on paper—and would be visible whenever individuals are choosing retirement options, including when new employees set up a 401(k)-style plan or if they roll those assets into an IRA.

A label that provides workers with consistent and straightforward fee information could help them make better-informed investment decisions as they choose retirement funds. In fact, a recent survey by the National Association of Retirement Plan Participants showed that 81 percent of 401(k) plan participants said that a standardized nutrition-style label would be useful in understanding fees.

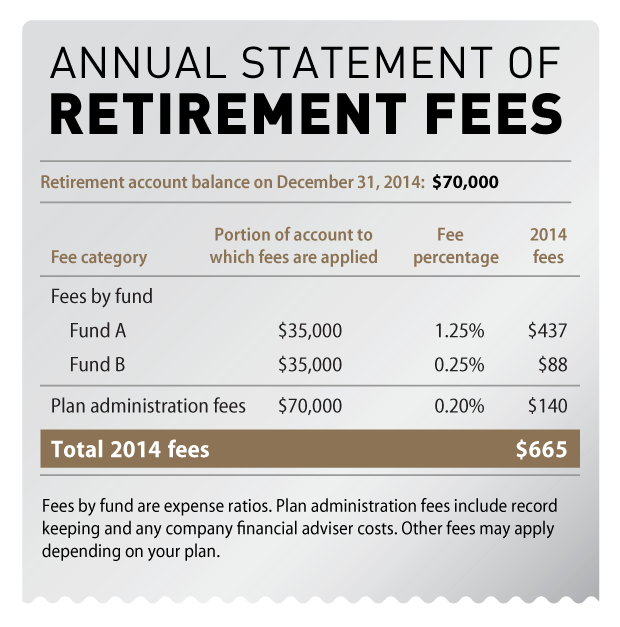

But here’s another new idea that could make a big difference for retirement savers. Financial firms should be required to send 401(k) and IRA investors a simple, easy-to-read annual receipt detailing how much investors spent that year on retirement fees, including both overall plan fees and investment-related fees. A similar, firmwide receipt should be sent to companies that manage 401(k) plans. These retirement receipts would remind workers and employers alike that their 401(k) funds are not free and arm them with facts allowing them make more-informed choices.

It is possible that retirement receipts could also include more information on comparability of fees and the performance of benchmark funds. Yet even at its most basic, the receipt could be incredibly straightforward and simply show what an individual investor paid that year in various fees.

If investors are able to more easily understand whether their fund choices are high cost or low cost, they will likely pay much closer attention to fees. After all, the average 401(k) balance was more than $72,000 at the end of 2013. So even with fees totaling 1 percent, a typical investor could receive an annual retirement receipt detailing more than $700 in fees—enough to get many peoples’ attention.

If better information through retirement labels and retirement receipts led even half of 401(k), 403(b), 457, and IRA mutual fund assets to be invested in funds that save investors 0.50 percent annually, American workers could save $17.5 billion in a single year alone.

So how do we help America’s struggling middle class? One receipt at a time.

Jennifer Erickson is the Director of Competitiveness and Economic Growth at the Center for American Progress. David Madland is the Managing Director of the Economic Policy team at the Center.

*Authors’ note: This calculation uses data from the Investment Company Institute, or ICI, on the amount of assets in U.S. retirement accounts in the fourth quarter of 2014. The ICI provides the estimated value of 401(k), IRA, 403(b), and 457 defined contribution accounts held in mutual funds as follows: $2.868 trillion in 401(k) plans, $3.546 trillion in IRAs, $456 billion in 403(b) plans, and $112 billion in 457 plans. These accounts have a total value of $6.982 trillion. Investing half the total value of 401(k), 403(b), 457, and IRA assets held in mutual funds into funds with fees 50 basis point lower than the funds in which they are currently invested would result in savings of $17.455 billion over a single year.