The U.S. government taxes the worldwide income of U.S. multinational corporations, but profits earned overseas are not actually subject to tax until a company repatriates them or brings them home. To avoid double taxation when “deferred” earnings are repatriated and taxed, companies receive a credit for any foreign taxes already paid on them. For obvious reasons, multinationals have a strong incentive to keep their profits offshore for as long as possible, and they very creatively use tax-law loopholes to avoid repatriation and taxation.

How exactly do they do this? Basically, multinationals use a variety of business transactions and accounting schemes that enable them to take advantage of loopholes in the laws that govern the taxation of U.S. companies’ foreign-sourced income. These tactics have the effect of shifting income to foreign countries—preferably to low-tax countries. Sometimes the U.S. company actually merges with a foreign company—perhaps even with its own subsidiary—and moves its headquarters out of the United States. This is referred to as a corporate “inversion.” Most of these tactics are accomplished on the books—through accounting transactions or stock purchases, for example—and may not actually involve people, products, or machinery moving across borders. While there may be nontax reasons for some of these profit-shifting activities, they are often simply a paper transaction made in an attempt to avoid U.S. taxation.

From 2009 to 2013, the corporate tax represented only 6.6 percent to 9.9 percent of total federal tax receipts. The ability of multinational corporations to defer U.S. taxes on their foreign earnings is a big reason why corporate tax receipts are so low.

Repatriation holiday proposal

Recently, an idea has resurfaced to allow multinationals a “repatriation holiday.” This idea, which was last carried out in 2004, gives multinationals a short window of time to bring home their foreign earnings at an extremely low tax rate.

Proponents say that a repatriation holiday would let everybody win: The federal government would get a big chunk of tax revenue and the foreign earnings would come home, where they would increase domestic investment and employment. Proponents also argue that there are huge amounts of deferred foreign earnings “trapped” overseas and that U.S. multinationals cannot afford to bring them home because the United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the world.

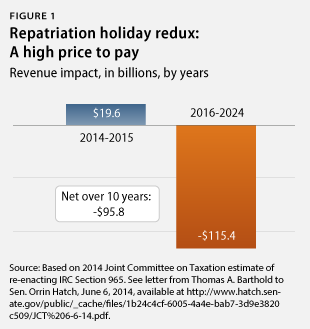

According to a Joint Committee on Taxation, or JCT, estimate, however, a repatriation holiday would cost the U.S. government $36.7 billion in lost tax revenue over five years and $95.8 billion over 10 years. The projections were made at the request of Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT), who asked the JCT to estimate the revenue impact of a re-enactment of Internal Revenue Code Section 965, the 2004 repatriation holiday. While JCT found that the provision raised revenue in the first two years, it said this would be followed by eight years of substantial revenue losses. This is in part because a significant portion of the foreign profits repatriated during a short holiday period consists of profits that eventually would have been repatriated anyway. This means they would have been taxed at normal corporate rates. In addition, research strongly suggests that allowing a second repatriation holiday will lead taxpayers to delay repatriation of earnings after the holiday window closes in anticipation of yet another holiday in a future year.

Furthermore, the last repatriation holiday was not followed by a significant increase in domestic investment among the corporations that took advantage of it. On these grounds, therefore, the proposal’s revenue loss clearly is not worth it.

Deferred earnings of U.S. multinationals not “trapped” overseas

Companies can use deferred profits to accomplish their business goals in the United States without repatriating and paying taxes on them. The funds that are supposedly sitting in foreign accounts can be—and often are—deposited in U.S. bank accounts. The company that owns them cannot spend them directly on itself, but it can invest them in U.S. Treasury bonds or in other U.S. corporations without being required to pay taxes on them. In addition, U.S. banks will gladly make loans to a U.S. company with large deferred earnings accounts because they know the company can repatriate the funds later, if necessary, to pay off the loans. In this manner, the company can effectively access its foreign earnings for any purpose in the United States without paying tax on them until later.

According to the White House and the Department of the Treasury, when all types of taxes and tax-related factors are taken into account, the effective tax rate on U.S. corporations is in line with that of our major competitors. While it’s true that the U.S. statutory corporate tax rate of 35 percent is the highest among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, there are many factors that affect what taxes corporations actually pay and what impact the taxes have on those corporations’ investment incentives. Depending on how these factors are incorporated into a more comprehensive measure, the effective tax rate on U.S. corporations will be somewhat above or below the average, but it will not be way out of line.

Alexandra Thornton is the Director of Tax Policy on the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress.