Politicians, it seems, always crave credit for the creation of new jobs in their communities; but in a free market economy, governments play only a partial role when it comes to determining where businesses locate and who they hire. Still, in today’s headline-focused media culture, short-term political optics often outweigh reality, and elected officials spend considerable time and effort to spur economic development—especially at the state and local levels.

In many places, the economic development game plan consists of offering incentives to a select number of firms based on a narrow set of criteria, such as industry type or employment levels, instead of ensuring robust investment in education, workforce training, infrastructure, and other essential public goods. While state and local tax incentives for small to midsize companies have tripled since 1990, efforts have increasingly shifted toward moonshot strategies—massive proposals aimed at luring extremely large corporations that hold the promise of significant jobs and investment, but which often come at an extremely high per-job cost.1 Examples of the strategy abound, including semiconductor manufacturer GlobalFoundries in New York; the Boeing Corporation in Washington and South Carolina; foreign automakers in southern states; and, more recently, the electronics manufacturer Foxconn Technology Group in Wisconsin as well as Amazon in its yet-to-be-determined second headquarters (HQ2) location.

Unfortunately, elected officials, fixated on short-term political interests, promoted the positives of these incentives—jobs and economic growth—while minimizing or ignoring the downsides—financial and opportunity costs. Their decision to do so is completely rational. The announcement of a deal between a government and a company typically includes the promise of jobs retained or created and millions of dollars in new investment. These benefits are a politician’s dream because they create immediate positive headlines. In fact, one public finance expert calls it the “ribbon-cutting syndrome.”2 Meanwhile, any negatives, such as companies failing to deliver on their promises, come to light much later and often receive less attention. And in some cases, companies even started construction on a new facility while still pursuing incentives to locate there.3

A recent case in point: then-presidential candidate Donald Trump initially criticized United Technologies Corporation for its announced plan to move one of its Carrier manufacturing facilities from Indiana to Mexico, insisting that “they have to pay a consequence.”4 Following Trump’s election, the consequence ended up being a deal negotiated by then-Indiana Gov. and Vice President-elect Mike Pence—on behalf of the president-elect—giving United Technologies $7 million in state tax breaks over the course of a decade.5 In return, the company would only move about two-thirds of the 2,100 jobs originally planned and keep the plant open.6 The deal garnered positive headlines for the incoming administration, such as “Carrier to keep about 1,000 U.S. factory jobs in deal with Trump.”7

Ironically, the deal hammered out to keep the Carrier plant in Indiana was quite the change from what Trump said on the campaign trail, where he railed against corporate giveaways. During a visit to Wilkes-Barres, he said, “Here’s a low-interest loan if you stay in Pennsylvania. Here’s a zero-interest loan. You don’t have to pay. Here’s a this. Here’s a tax abatement of any kind you want. We’ll help your employees. It doesn’t work, folks. That’s not what they need. They have money.”8

Trump was not wrong when he said that the strategy “doesn’t work.” In May 2017, despite the tax breaks, Carrier’s Indianapolis plant notified the state of Indiana of its intention to lay off 630 employees during the second half of the year.9

In order to receive a total of $5 million in job retention tax credits, $1 million in training tax credits, and $1 million in capital investment tax credits, Carrier must keep at least 1,069 full-time employees, provide training for at least 900 of them, and make a minimum of $16 million in investments for up to 10 years.10 Former employees argue that hundreds of the jobs that remain are administrative and engineering office positions that were never going to be relocated.11 Carrier’s CEO also indicated that the investments would go toward automation technology that would further reduce the number of jobs.12

Thrust into the 2016 campaign as an issue emblematic of offshoring quality jobs, Carrier received an inordinate amount of attention and the president-elect received political benefits, but the deal did not turn out to be in the best interest of workers. Most other economic development incentive deals happen with far less scrutiny, abetted by underappreciation of their true costs and overall impacts.

Underlying the commonly held misperception of the utility and necessity of incentives are implicit and explicit beliefs that incentives are consequential to firms’ location decisions, that benefits always outweigh costs, that incentives are the best economic development strategy, and that competition amongst locales is inherently good. Survey respondents have indicated that they view governors who secured private investments with incentives more favorably than governors who secured private investments without them.13 This issue brief confronts several overlapping misunderstandings, using examples in order to show the limits of incentives—in essence, providing a reality check.

Reality 1: Economic development incentives often are not crucial to where firms locate

Firms looking to locate or relocate often overemphasize the impact that subsidies have on their decisions. They have good reason to do this since exaggerating the impact might encourage a state or local government to offer a more robust incentives package.

The reality is businesses place far more weight on other considerations. For example, in its request for proposal for HQ2, Amazon mentions incentives as part of “key preferences and decision drivers.” However, it also emphasizes real estate and siting availability; a talented workforce and education pipeline; sufficient infrastructure for workers commuting as well as for national and international travelers; and a community with a high quality of life.14 When ruling out Detroit, the Amazon executive leading the search blamed the absence of a regional transportation network and an insufficient number of workers prepared to take the influx of jobs—not its insufficient tax breaks.15 Minneapolis-St. Paul heard similar concerns about hiring and recruitment.16 It is no coincidence that places that possess these desirable characteristics, such as the Washington metro area, New York, Boston, and Los Angeles, are among the finalists for a top-tier technology conglomerate.17

In 2015, ConAgra Foods moved its headquarters from Omaha to Chicago. Nebraska offered $28.5 million in incentives, which was more than twice Illinois’ $13-million offer.18 In explaining the move, ConAgra CEO Sean Connolly did not mention the role of incentives but instead pointed to “strategic needs of [the] business” and the fact that its new downtown location would put it at “the heart of one of the world’s business capitals.”19

The failure to do strategic economic development has subjected nearly every community and state to a zero-sum game of providing company-specific incentives in seemingly haphazard ways.20 Distribution and logistics warehouses frequently receive economic development subsidies. The accountability nonprofit Good Jobs First tracks the subsidy packages that Amazon has received for its fulfillment and data centers, which now total nearly $1.4 billion nationally.21

Supply chain facilities have limited geographic flexibility. In other words, if a company needs a regional distribution center to serve the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area, one would expect the distribution center to locate in the metro area. However, the company could consider dozens of location options in a variety of cities within the region, making it possible to extract incentives out of local governments and choose a high bidder.

The amount businesses pay in state and local taxes is far less than what they typically imply. Two studies estimate that businesses’ state and local taxes account for less than 2 percent of the total costs of doing business, on average, nationally.22 Other costs, such as wages and benefits, are far more substantial, so it makes sense that the impact of reducing a specific business’s tax burden has only modest effects on location decisions.23

The use of property tax incentives in Texas provides compelling evidence—based on dozens of examples—that locational decisions are not highly correlated with economic subsidies. A unique Texas law grants school districts substantial power to subsidize a business’s taxes on new property. Because the state has no income tax, in 2015, property taxes comprised 42.0 percent of Texas’ state and local revenues, far exceeding the national average of 31.1 percent.24 That year, nearly 54 percent of the state’s property taxes were levied by school districts, so reducing school-funding property taxes for businesses has become a ubiquitous tool for economic development.25

Under the Texas Economic Development Act, also known as Chapter 313 of the state’s tax code, school districts have a unique role that allows them to determine the outcome of a business’s application to the state comptroller for incentives, permitting local governments to reduce businesses’ property tax liabilities in exchange for building or expanding property and creating jobs.26 Companies can entice school districts to approve applications by agreeing to supplemental payments—essentially payments in lieu of tax (PILTs or PILOTs)—to the district out of the business’s tax benefits.27 Unlike property taxes, supplemental payments are not part of state school aid formulas, making them, in effect, fiscal transfers from the state government to the company, meaning that the school districts have little incentive to exercise caution in their usage.

Proponents believe that Chapter 313 is a critical tool for economic development, echoing a common argument: Forgone taxes are worth it because they create new revenues that the government never would have collected without subsidies.28

Since Chapter 313 established a standardized process for receiving this incentive, Nathan Jensen, a University of Texas at Austin professor, analyzed businesses’ applications for school property tax relief. His findings suggest that just 15 percent of participating firms needed the incentives in order to make an investment in Texas. Furthermore, many of the other firms were uncharacteristically open that incentives were not a necessity. The author cites instances in which companies applied for incentives after completing a project and asserts that both school districts and the comptroller’s office were aware of the program’s widespread ineffectiveness.29

Reality 2: Benefits from incentive deals may not live up to the promises

Decades of stagnant wages and the disappearance of good jobs have put tremendous pressure on millions of working families across the country.30 Voters frequently cite the economy as their top election issue, so elected officials look for ways to be responsive to those concerns.31

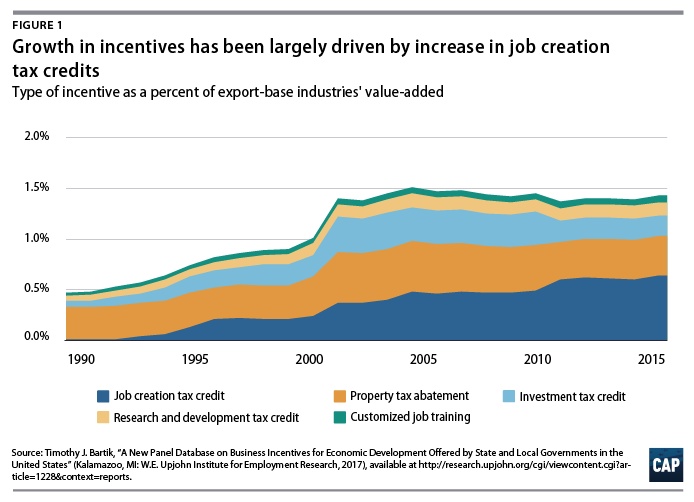

Creating good-paying jobs is a difficult task, so it is enticing to simply trade away some tax revenue in exchange for the addition or preservation of jobs—whether it be 10 or 1,000 jobs. Incentives as a share of value-added increased substantially in the late 1990s and early 2000s, primarily due to the increase of job creation tax credits.32

However, some local officials have begun resisting the temptation. For example, Mayor Sam Liccardo of San Jose, California, says that subsidies are “a bad deal for city taxpayers.”33 The administration of the nation’s tenth-largest city would rather focus on the workforce, citing a statistic that only 5 percent of job growth in Santa Clara County—which includes San Jose—comes from “move in” businesses.34 Similarly, in San Antonio, the nation’s seventh-largest city, the mayor and county judge wrote to Amazon declining to participate in its HQ2 search, saying, “blindly giving away the farm isn’t our style.”35

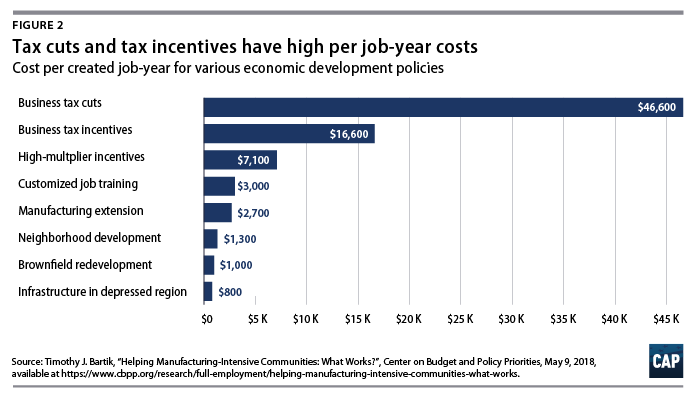

The academic literature tends to reinforce these mayors’ approaches. Incentives, while better targeted than broad tax cuts, are not particularly cost-effective, and research questions what, if any, impact incentive programs have on overall economic activity.36 According to one study, on a per job-year created basis, business tax incentives cost an average of $16,600 across more than 100 manufacturing-intensive high-population local labor markets.37 Neighborhood development, brownfield redevelopment, infrastructure investment, and customized job training strategies had substantially lower costs per job-year, making them a far better use of resources. The author of the study, labor economist Timothy J. Bartik, wrote, “I find no evidence that job growth in these areas is significantly spurred by cutting business taxes or increasing business tax incentives.”38 Other findings reach a similar conclusion. One evaluation of the Kansas City region discovered that there was no statistically significant difference in new job creation between companies that received incentives from the Promoting Employment Across Kansas (PEAK) initiative and those that did not.39

With rapidly increasing demands for cloud computing and online storage, many large tech corporations are establishing data centers throughout the country, and state and local governments are willing to pay them to do so. Data centers are essentially racks of servers that require little more than land, tons of cheap energy, and just a few workers. Still, Apple received $213 million for a 50-employee data center in Iowa; Facebook will receive $150 million for a Utah data center with fewer than 50 employees; and Google has taken advantage of property tax exemptions for its facilities in Oklahoma.40

With rapidly increasing demands for cloud computing and online storage, many large tech corporations are establishing data centers throughout the country, and state and local governments are willing to pay them to do so. Data centers are essentially racks of servers that require little more than land, tons of cheap energy, and just a few workers. Still, Apple received $213 million for a 50-employee data center in Iowa; Facebook will receive $150 million for a Utah data center with fewer than 50 employees; and Google has taken advantage of property tax exemptions for its facilities in Oklahoma.40

The economic development commitments that state and local governments make to companies can last decades. Wisconsin has committed to giving refundable tax credits to Foxconn until 2033.41 The Michigan Economic Growth Authority’s (MEGA) tax credits have a remaining liability of $7 billion lasting until 2030.42 As of 2015, 95 percent of the Michigan Economic Development Corporation’s outstanding tax credits targeted maintaining current jobs at credit-receiving companies.43

Incentives are frequently front-loaded, which can add considerable risk for governments.44 It is unlikely that the involved elected officials will stay in office for the entirety of the commitments they made. Moreover, it is uncertain that the company will still be in business. The average S&P 500 company stays in business fewer than 20 years, and the typical company has a lifespan of 10 years, regardless of sector.45 Even with due diligence, the idea that a government may use taxpayer dollars to subsidize a company that may not exist by the time its expected incentives run out—much less by when the promised benefits are realized—should give taxpayers serious concerns. This was exactly the case involving a Pennsylvania plant to build Volkswagen Rabbits in 1978. After winning a national competition by promising tens of millions of dollars in state incentives, Pennsylvania saw Volkswagen close its factory less than a decade later following insufficient U.S. demand for the car.46

Investments in infrastructure or human capital do not leave with a company.

Similarly, in January 2018, consumer product company Kimberly-Clark announced plans to close two manufacturing facilities in Wisconsin.47 The announcement was part of Kimberly-Clark’s 2018 Global Restructuring Program, which aims to cease production at 10 manufacturing facilities, exit low-margin markets, and lay off up to 5,500 workers in order to save several billion dollars.48 Confronting the loss of 600 jobs in their state, Gov. Scott Walker (R) and some Wisconsin state legislators offered the company the same level of incentives as Foxconn, including subsidizing wages by 17 percent and capital improvements by 15 percent.49 The estimated per job per year subsidy is $15,000 to $19,000, an amount that is far more expensive than $2,500 per job per year—the average incentive amount for other deals.50 The enabling legislation passed the state Assembly but never received a vote in the state Senate.51

Perhaps there has been a realization that after one large company receives a deal, a state legislator or city council member will be forced to make decisions about where to draw the line for others. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon told investors that he would work to get the winning location of the HQ2 contest in order to give his company the same benefits as Amazon.52 This puts elected officials in the position of determining whether JPMorgan Chase and other companies should receive subsidies on par with Amazon.

When a company relocates after receiving subsidies, it is difficult, sometimes impossible, for a government to claw back those incentives. Investments in infrastructure or human capital do not leave with a company. These public goods stay with places and workers for the long term, enabling other companies to make use of them in their business models.

Incentives are subject to “the law of the hammer,” that is to say, if the only tool one has is a hammer, everything begins to look like a nail. Even though they have other options for economic development, state and local governments want to bring jobs and investment to their communities and see company-specific incentives as an easy and conventional solution. However, if used incorrectly, much like a hammer, these types of subsidies run the risk of long-term damage.

Reality 3: Subsidies may result in diminished public services

Advocates often fail to give the complete context around a potential deal and exclude public costs, potential displacement of existing firms, and opportunity costs of using resources in other productive ways. Granted, some economic development deals undoubtedly do have measurable positive benefits in terms of jobs and increased investment. Proponents commonly frame a deal in terms of benefits that would not or could not happen in its absence. In some ways, it is a trickle-down strategy at the local level—financial incentives targeted toward a single company with the promise that the community and its residents will benefit from the job creation and investment that follow.

Recently, Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) defended Maryland’s incentives legislation for Amazon’s HQ2—Promoting ext-Raordinary Innovation in Maryland’s Economy (PRIME) Act of 2018—saying, “We’re actually letting the corporation keep some of its future revenues that we’re not getting now in taxes if they create all these jobs.”53

However, the more relevant consideration is, what are the costs of the agreement relative to the gains? Any financial incentives will be derived from government revenues and, ultimately, from taxpayers. Since state and local governments must balance their budgets, financing a new deal, at least in the short term, must take the form of increased taxes on others, reduced spending on other priorities, or a combination of the two.

Despite a strengthening national economy, states have not been improving their fiscal stability. In 2017, 21 states had less in their reserves—frequently referred to as a “rainy day fund”—compared with 2008. Since 2010, more states have seen a downgrade in their bond rating than have seen an upgrade.54 Binding commitments to subsidize jobs and capital investments may be feasible now, but in the event of an economic downturn, states will have less revenue, potentially forcing legislators to cut other spending priorities in order to meet contractual obligations to companies.

Proponents often cite studies, prepared by hired economic consulting firms, which estimate additional economic activity and new jobs that would occur solely because of a new project. In the case of Amazon HQ2 in Maryland’s Montgomery County, just outside of Washington, D.C., one such study predicted that the project would have an economic impact of $17 billion annually while supporting more than 100,000 jobs and hundreds of millions in state and county tax revenues.55

Montgomery County, one of the wealthiest, densest, and most populous counties in the nation, already faces a fiscal year 2018 budget shortfall of $120 million despite a strong national and local economy.56 If Amazon put HQ2 in Maryland, it would mean at least 50,000 additional workers in Montgomery County—an increase of 10 percent—and an additional 300,000 to 1 million residents in the region over the next decade or so.57

Many of those workers and their families would choose to reside near the new headquarters, and tens of thousands of additional people would commute to and from the county daily. This would expand the tax base, leading to new revenues, but also result in new social costs, including pressures on the school system, affordable housing, and transportation networks. Marc Elrich, the Democratic nominee for Montgomery county executive, supports Maryland’s $8.5 billion Amazon plan but admits that “schools is the thing where we’re going to need help.”58

If public spending fails to match the needs of a growing population, there is substantial risk of deteriorating essential public services that would have negative impacts on all new and existing county residents, but especially on low-income households that are disproportionately in communities of color.59 Examples highlighting such a scenario are evident elsewhere. Wisconsin’s Legislative Fiscal Bureau, for instance, projects that the state will have to divert up to $90 million of its funding for local roadwork to pay for construction related to Foxconn.60

Amazon’s 50,000 projected employees would make up less than 1.5 percent of the 3.4 million people in the current Washington metro area labor force.61 Furthermore, there is no information about how many HQ2 employees would be existing metro area residents. An employer such as Amazon is looking for highly qualified employees with specific skills. Even if some potential employees are local, companies may look to hire from elsewhere, often encouraged by financial incentives for nonlocal employees. For example, Washington’s proposal for Amazon HQ2 offers new hiring credits of up to $10,000 per employee. If the employee is a new hire from outside of the district, Amazon is eligible for an additional subsidy of up to $5,000 against corporate franchise tax liabilities.62 When in-migrants take some of the jobs created as part of an incentive deal, it diminishes the per capita growth effects.63

Montgomery County and Washington are only two of 20 finalists for Amazon HQ2, but they are by no means unique in their characteristics. Other finalist locations, many of which are the most thriving metropolitan areas in the country, already struggle with rapid and uneven growth, furthering inequality and income segregation.64 These growing cities are already constrained by an inability to raise sufficient revenues to provide public services. It is not clear how Amazon, or any company receiving economic development subsidies, would improve their fiscal situations.

Moreover, there also appears to be a connection between tax incentives and inequality. Out of a sample of the largest U.S. cities and counties, the magazine Governing found that the 100 places with the highest inequality, measured by the Gini index, had the highest median tax abatement per capita.65 The analysis did not conclude that incentives worsen inequality, but results suggest that incentives frequently go to desirable employers such as those with name recognition or those in high-paying sectors. Based on data between 2008 and 2014, Good Jobs First found that large companies with at least 100 employees got 80 to 96 percent of the incentive dollars, but these firms account for less than two-thirds of private sector employment.66

The inequality is apparent in Sparks, Nevada. Following the arrival of Tesla’s battery factory in 2014, property values and rents have boomed, pushing many people whose fortunes fall outside of the margins of Tesla’s impact toward housing insecurity. The city has been unable to assist its residents. Its revenue growth has barely kept up with inflation, even as population growth tests the limits of its existing resources.67

Every dollar that goes to subsidizing an incentive-seeking company is a dollar that cannot be used to mitigate the costs of its impacts.

Seattle, home to Amazon since the company’s beginning, provides a lesson in how a city adapts to an influx of workers with high-paying jobs. The city has struggled to confront the effects of its growth.68 To underscore the city’s challenge, Seattle planned on taxing larger employers in order to address the lack of affordable housing and the rise in homelessness, which has increased 44 percent between 2015 and 2017.69 Under the city’s Employee Hours Tax, businesses with annual gross revenues of $20 million or more would pay an annual tax of 14 cents per Seattle-based employee per hour: up to $275 a year.70 After Seattle passed its large employer tax, the local business community—including Amazon and Starbucks—organized an effort to put a repeal initiative on the ballot during this November’s election. Instead of permitting a months-long campaign, Seattle’s council voted to repeal the tax, bringing the city back to square one on dealing with its housing issues.71

Silicon Valley cities have begun to discuss implementing their own employee headcount taxes targeted at the largest tech companies. Lenny Siegel, mayor of Mountain View, California—home to Google—cites the disparity between growth of jobs and lack of public improvements, saying, “These are all job-rich cities, where employment has been growing rapidly, and housing and transportation have not.”72

No matter the location or the firm, there is an inescapable dichotomy: Every dollar that goes to subsidizing an incentive-seeking company is a dollar that cannot be used to mitigate the costs of its impacts. The source of the funding matters immensely. One model predicts that if a state gives away 1 percent of its personal income by cutting education spending, per capita income statewide would decrease 4.4 percent.73 Urbanist Richard Florida succinctly describes the trade-off between incentives and public services: “They say publicly we want a sustainable community, a community with transit and affordable housing. How do you get that community if you don’t pay taxes?”74

Reality 4: Governments competing for businesses by providing incentives is often a zero-sum game

Competition is often considered a virtue in political economics. For businesses, it drives innovation and creates efficiencies, allowing more to be produced at a lower cost. For nonfederal governments, it forces policymakers to make decisions in order to generate the amount of revenue necessary to provide an optimal level of public services desired by the typical resident. This is the basis of the Tiebout model, which hypothesizes that people vote with their feet, deciding where to live in part based on their desire for public services and their willingness to pay for them.75 Firms make similar decisions, valuing things such as infrastructure, workforce, and natural resources, based on industries and business models. If state or local governments want to be attractive to certain types of businesses, such as tech companies or small businesses, then they should set public policies to reflect those goals.

Offering incentives deal by deal or passing legislation narrowly written for a single company in order to win a competition is bad tax policy. In one survey of economists, only 5 percent of respondents agreed that the country “as a whole benefits when cities or states compete with each other by giving tax incentives to firms to locate operations in their jurisdictions.”76 If governments want to encourage certain kinds of commerce, they should not spend tax revenues on businesses that are the largest or most well-known. Instead, public officials should set broader policies that allow more businesses to benefit.

The failure to do strategic economic development has subjected nearly every U.S. community and state to a zero-sum game of providing company-specific incentives in seemingly haphazard ways.77 Evan Mast of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research has studied the relationship between the geographic density of New York state’s industrial development agencies and the level of competition. Mast’s research shows that when there is a higher concentration of development agencies who can offer incentives in a given area, there are greater probabilities that a company receives incentives and that those incentives are larger.78

The belief that local governments must participate in this contest to catalyze job creation might well be misplaced. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the arrival of a new Amazon fulfillment center does not add to net private sector employment in a county.79 Between 2015 and 2017, Amazon opened at least 32 new fulfillment centers across the country.80 It is plausible that local jobs just shifted from other sectors to warehousing, but wages for jobs in the sector did not increase. A worker previously employed in a different occupation, such as retail sales, may not necessarily see a wage boost by taking a warehouse job; in 2017, the median companywide Amazon compensation was $28,446.81

Much of the information companies need to make location decisions is publicly available. With Amazon’s list of preferences in hand, the finalists were mostly predictable. The key information the company lacked was the types and levels of incentives the cities and states were willing to provide as well as what real estate would be made available.82 Combined with its more than 330 active distribution facilities—including fulfillment centers—Amazon is gathering a uniquely robust level of information about these places for potential future locations.83

Reality 5: Transparency and evaluation of incentives are minimal

Lastly, competitive deals for targeted incentives frequently happen through opaque processes, and governments may never plainly disclose total tax expenditures. States can set their own transparency measures, but there is considerable variation among states and even among programs in the same state.84 States carry out little, if any, evaluation of a tax expenditure’s effectiveness at achieving its stated goals.85 Taxpayers would not accept a comparable lack of transparency on infrastructure or education spending from a public entity; they should have the same expectations when it comes to incentive agreements.

There have been some efforts to improve information-sharing requirements, but they have been inadequate. In 2015, the Governmental Accountability Standards Board (GASB), the accounting standard-setting organization for state and local governments, updated its rules so that governments must disclose tax abatements, including types and amounts.86 GASB does not, however, require disclosure of the quantity of agreements, the recipients’ names, or estimates of future lost revenues.87

This closed-off and opaque process has been noteworthy as cities and counties have submitted their HQ2 bids to Amazon. Some governments—such as the state of Rhode Island and the cities of Chicago and Charlotte, North Carolina—refused to make public the information that they gave to Amazon in their proposals, even after open records requests.88 Montgomery County did comply with a request for its proposal but redacted every single line of the document.89 Officials fear they would put themselves at a competitive disadvantage with other governments if they were to reveal information that they consider akin to a “trade secret.”90

Some states and cities went as far as submitting their bids through outside organizations and chambers of commerce, exempting entire proposals from any public scrutiny.91 Some question whether the activities of regional economic development corporations are sufficient to satisfy the private benefit doctrine that prevents nonprofits from making decisions whose benefits to nonpublic entities are more than incidental.92 Of the 20 finalists, only Newark, New Jersey’s $7 billion bid was fully disclosed. The rest withheld some or all information about what the city or state offered Amazon.93

Conclusion

Economic development incentive deals frequently occur under the radar. Perhaps there will be a story in the local news when they involve an employer of community importance; but several recent high-profile relocation efforts have attracted immense amounts of national attention for a trivial amount of jobs in the context of the entire U.S. economy.

However, 50,000 jobs—or even 10,000 jobs—would have noticeable impacts to the economy at the local and regional levels, and companies closely follow public sentiment. Media reporting has suggested that companies have adapted their strategies to appear cognizant of criticisms such as impacts on housing and narrow geographic benefits.94 It seems that some companies have learned their lesson, but this does not change the fundamental reality that, far too often, economic development incentives are irrelevant to decision-making, fail to meet promised results, take away from existing or potential public services, lead to zero-sum competition among governments, and lack appropriate oversight. Until taxpayers demand accountability from elected officials who condone opaque and non-targeted deals, it is clear that we, as citizens, have not learned our lesson.

Andrew Schwartz is a policy analyst for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress.