This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS, today added to the evidence that the U.S. economy continues uninterrupted along a path of recovery, albeit a moderate path. U.S. employers add 209,000 new jobs in July, and the unemployment rate was basically unchanged at 6.2 percent. Revisions to older data showed the U.S. economy averaging job growth of 245,000 jobs per month for the past three months.

But today’s report also indicates both how far the recovery still has to go and the particular challenges posed by a job market creating a preponderance of low-paying, low-quality jobs. Both the quality and quantity of new jobs being created in the economy are weighing on inclusivity of the growth that is taking place.

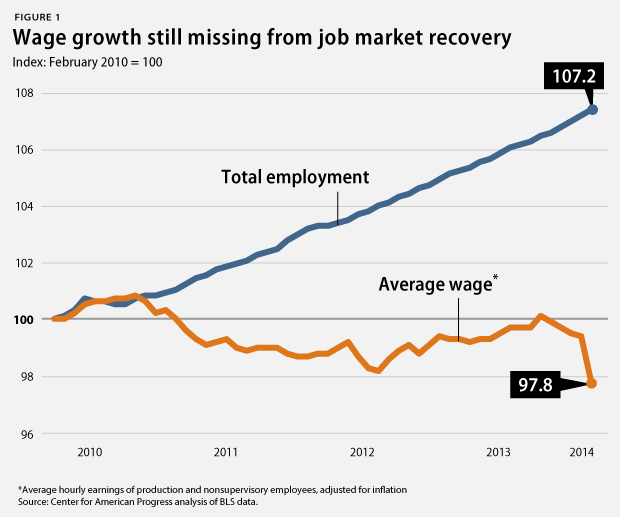

According to today’s report, the average wage for so called production and nonsupervisory workers—nonmanagerial wages—increased by just 4 cents in July to $20.61, not accounting for inflation. This measure tracks closely to the median wage and the average wage for the bottom 90 percent of income earners—broadly, the wage health of the U.S. middle class. In real terms, average middle-class wages now stand 2.2 percent below their level at the start of the labor-market recovery in February 2010, despite the economy steadily adding jobs. (see Figure 1)

Stagnant wages for U.S. workers stem from the kinds of jobs employers are creating, the still elevated level of unemployment, and policy choices that are standing in the way of broader employment creation and rights at work that raise wages.

For the economy overall, elevated unemployment remains a central problem. The July employment report shows that nearly 9.7 million job seekers are still out of work—3.2 million of whom have been out of work for 27 weeks or more. The share of the overall population employed stood at 59 percent in July, or basically unchanged over the past year and far from prerecession employment levels.

Key demographic groups continued experiencing disproportionately high unemployment in July. Unemployment for African Americans, however, moved against the trend, rising by 0.7 percentage points to 11.4 percent. The unemployment rate for Latinos held steady at 7.8 percent. Women, with an overall unemployment rate below the national average, saw unemployment increase by 0.4 percentage points in July.

The number of people working part time for economic reasons—because they cannot get enough hours—declined by 33,000 workers. But still, 7.5 million employees would like to be working and earning more, and a further 2.2 million individuals are marginally attached to the labor force—although they are not officially counted as unemployed looking for work.

Steady job growth drew more people out from the woodwork to look for jobs as the labor force expanded by 329,000 people, and 141,000 individuals re-entered the labor force in July. The financial squeeze faced by many retirement-age workers is also drawing people back into the labor force. For people 65 years and older, labor-force participation rose to 18.3 percent in July, up from an average of 15.4 percent in 2006, prior to the recession.

For the long-term unemployed, the probability of finding new employment has improved. However, their job prospects still remain below the prerecession level, according to new research from Federal Reserve economists Tomaz Canjer and David Ratner. The long-term unemployed still are only slightly more likely to transition to a new job than to exit the labor force altogether, their research shows. The share of workers who voluntarily left jobs in July remained basically unchanged, according to today’s BLS numbers.

Employers added jobs broadly across different sectors of the economy in July, with few gazelle industries bounding ahead of the herd. Beside from employment in manufacturing—which surged back with 28,000 new jobs added—the automotive industry and other transportation manufacturers accounted for more than two-thirds of these jobs. Employers in typically low-wage sectors, such as retail trade and accommodation, food service, and other leisure industries, added 27,000 and 21,000 new jobs, respectively, or together roughly one-fourth of overall private-sector job creation.

Two notable industries registered weaker than expected job creation: temporary help services and health care. Temp work, often a harbinger of future permanent hiring, grew by less than 9,000 jobs in July. Health care—which averaged more than 20,000 new jobs per month even during the Great Recession—added just 7,000 jobs in July.

Overall, the job market continues moving in a more positive direction. But millions of Americans still find themselves left in the lurch, and millions more are wondering what happened to their share of the economic pie.

Adam S. Hersh is a Senior Economist at the Center for American Progress.