Introduction and summary

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law in 2010, President Barack Obama achieved the most significant overhaul of the U.S. health care system since Medicare and Medicaid were enacted in 1965, expanding coverage to 20 million additional people and improving the quality of coverage for many more.1 While conversations about how to achieve universal health coverage have persisted for generations, calls to pass universal coverage legislation have intensified in recent years. Many people in the United States still lack affordable health coverage with benefits tailored to meet their needs, a reality that has been exacerbated by the Trump administration’s policies attacking health care. People in the United States are also increasingly championing additional reforms to rein in costs, improve quality of care, and make health care more affordable. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has exposed failures in the U.S. health care system and underscored the urgent need to rebuild a more equitable health care system that works for everyone. As Congress and the public continue conversations about how to achieve universal health coverage—and as the United States looks to rebuild and reform the health care system in light of a crisis that has laid bare its many weaknesses2—it is also critical for lawmakers to consider the extent to which new proposals cover a frequently threatened area of care: reproductive health.

Most other developed countries have achieved universal coverage, and U.S. policymakers and advocates have frequently drawn on these existing models for their own universal health care proposals. It is worth noting that the designs of universal coverage systems in other countries vary, particularly when it comes to the role of private insurance.3 The frequently discussed single-payer system, for example, involves the federal government as the primary payer of health care. In England, the National Health Service oversees the country’s health insurance system as well as owns and operates hospitals. According to a Commonwealth Fund report, 11 percent of the English population buys supplementary private insurance for more rapid access to care.4 In Canada, provinces and territories administer health insurance programs locally, and private insurance covers services excluded from government programs for two-thirds of the population.5 Other international health systems rely on heavily regulated private insurance. In Germany, more than 100 competing nonprofit health plans provide coverage to 86 percent of the population, while 11 percent of the population opts out of this coverage for substitutive private health insurance.6 In Switzerland, people are required to purchase private insurance through regional health insurance marketplaces.7

The Center for American Progress has developed a plan to achieve universal coverage that also has the potential to expand access to reproductive health care. The proposal—Medicare Extra for All, referred to as Medicare Extra in this report—would be available to all lawfully present individuals in the United States and include important improvements to the current Medicare program, such as an out-of-pocket limit; dental, vision, and hearing coverage; and an integrated drug benefit.8 In addition, employers could choose to continue to sponsor their own health plans. Employees would have the option to choose between Medicare Extra and the plan offered by their employer, while people enrolled in the Federal Employees Health Benefits program, Medicare, TRICARE, or Veterans Affairs medical care could decide to opt into Medicare Extra or remain on their current plan. Importantly, reproductive health care would be more strongly embedded into the reformed health system envisioned by Medicare Extra. Health care proposals recently introduced in Congress—including Medicare for America,9 which is based on the Medicare Extra framework—are bold steps toward advancing access to reproductive health care and aim to reverse many years of attacks on family planning services and providers.

Decades of unnecessary, burdensome policies have resulted in barriers that make accessing reproductive health care difficult, if not impossible. With the United States being home to 68 million women ages 13 to 44, it is important for the federal government to ensure that reproductive health services are both accessible and affordable.10 All health care proposals under consideration should offer comprehensive coverage that not only protects and expands these services but also integrates them into any health system transformation. This report details the scope of current federal coverage as well as recent attacks on reproductive health care and access. Additionally, the report discusses how universal health coverage proposals such as Medicare Extra as well as bills currently under consideration in Congress can meet the shortfall in access to reproductive health care and strengthen coverage of these important services.

Access to reproductive health care in America

The fractured nature of the U.S. health insurance system means that access to reproductive health care depends on whether a person has insurance coverage and if that coverage is obtained through Medicaid, an individual insurance plan, employer-sponsored private insurance, or another program. Following the implementation of the ACA, more than 20 million Americans gained coverage, and the uninsured rate reached an all-time low for people of all races, ethnicities, incomes, and education levels.11 The ACA greatly benefited certain groups that have historically experienced disparate access to health care: Latinos saw the highest increase in coverage of every racial and ethnic group, while Blacks, Asians, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives also gained coverage at higher rates than white people.12 However, inequities in coverage persist: In 2017, 19.9 percent of Latinas and 13.7 percent of Black women were uninsured, compared with 8.0 percent of white women.13

In addition to reducing the national uninsured rate, the ACA sought to improve the quality of coverage offered. The individual and small-group market, in particular, has historically not offered standardized benefits across states and insurance companies, which has resulted in people paying more out of pocket or being denied coverage for certain services.14 The ACA addressed this problem by requiring most health plans to cover a defined set of women’s preventive services—including birth control, well-woman visits, and screenings for cervical cancer, HIV, and interpersonal and domestic violence, among other services—without cost-sharing, such as copays and coinsurance, which patients pay when visiting providers or picking up prescriptions.15 As a result, 61.4 million women currently have access to these preventive services with no out-of-pocket costs,16 and women have saved $1.4 billion per year on birth control alone.17 Additionally, the ACA required that individual and small-group plans cover 10 broad categories of services, known as essential health benefits (EHBs), including maternity and newborn care.18 Indeed, 8.7 million women are estimated to have benefited from maternity coverage following implementation of the ACA.19 While abortion cannot be listed as an EHB under law, states can require abortion coverage and insurers can elect to include abortion and abortion-related services in their plans.20 Research has found that in the absence of state prohibitions on abortion coverage, most private insurers elect to cover abortion without restrictions: Data from 2011 found that 90 percent of employer-sponsored insurance plans, a market where states are generally unable to impose restrictions that limit abortion coverage, covered abortion services.21

Medicaid, the federal health care program that serves low-income Americans, has historically been a key source of coverage for reproductive health care. The program provides access to a wide range of reproductive health and pregnancy-related services, such as contraceptives, maternity care, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and breast and cervical cancer screening, with no or low cost-sharing.22 Medicaid covers around 25 million adult women, two-thirds of whom are ages 19 to 49.23 It is the largest source of public funding for family planning, accounting for 75 percent of all public funds spent on family planning services and supplies.24 Additionally, the program finances almost half of all births in the United States.25 However, Medicaid has not been made available to all people with low incomes due to categorical eligibility requirements, including disability status, citizenship requirements, and the requirement to be a caretaker of a dependent child.26 Under the ACA, states have the option to expand Medicaid eligibility. The people covered in the program as a result of Medicaid expansion are entitled to the benefits afforded under EHBs and women’s preventive services, including birth control.27

The ACA also made significant strides in prohibiting discrimination in the health care system, particularly against women and LGBTQ people, ultimately increasing access to reproductive health services. Specifically, the ACA prohibits individual and small-group health plans from engaging in gender rating, which is the practice of charging women more than men for the same coverage.28 Additionally, the ACA prohibits most plans from denying coverage or charging people more for preexisting conditions.29 In the past, insurers routinely considered breast cancer, irregular periods, and even pregnancy to be preexisting conditions.30 Moreover, Section 1557 of the ACA—also known as the Health Care Rights Law—prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, race, national origin, age, and disability. The Obama administration interpreted the Section 1557 statute to prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity, sex stereotyping, and pregnancy, including termination of pregnancy.31

Another vital program, Title X, is the nation’s only domestic family planning program. It serves more than 4 million low-income and uninsured women and men each year, providing services such as birth control, HIV and STI testing and treatment, and cervical and breast cancer screenings.32 The program is of particular importance to uninsured individuals, including those who do not qualify for financial assistance to purchase private insurance and those who do not qualify for Medicaid due to citizenship requirements, as well as individuals who live in nonexpansion states and have fallen into the Medicaid coverage gap.33 Furthermore, many people who do have health insurance have come to rely on the confidential, high-quality care available at Title X family planning health centers for a number of reasons: They may face a dearth of providers in their geographic areas;34 other health centers may not accept their health insurance due to low Medicaid payment rates;35 or patients may simply prefer to access care from a reproductive health expert.

Since the ACA was signed into law in 2010, the breadth and scope of coverage for reproductive health services and the number of people who regularly access these services have increased dramatically, despite repeated attempts by conservative actors to impede these important health programs. However, disparities in access and coverage remain, with low-income women, women of color, young women, and immigrant women facing continued barriers to equal access.

Attacks on reproductive health care

Despite recent advancements, the ability to access comprehensive reproductive health services has not been realized for all. A prime example is abortion coverage, which is frequently carved out of health coverage proposals and laws. Since 1976—three years after the U.S. Supreme Court decided in favor of Roe v. Wade—Congress quickly moved to enact the Hyde Amendment to prohibit abortion coverage under certain health programs.36 This annual appropriations amendment continues to restrict federal Medicaid dollars from funding abortion services today, limiting access to reproductive care for low-income women and women of color—the populations most likely to benefit from the Medicaid program due to systemic racism, poverty, and sexism, which create barriers to accessing private insurance plans. Indeed, in 2018, 30.7 percent of Black women and 27 percent of Latinas ages 15 to 44 were enrolled in Medicaid, compared with 15.5 percent of white women in that age range.37 These restrictions also preclude abortion coverage for Native Americans, federal employees, military personnel, people in federal detention, and residents of Washington, D.C., among others.38

Under the Trump administration, attacks on reproductive health care—particularly abortion-related services and birth control—have increased to unprecedented levels. These recent attacks include but are not limited to:

- Attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Conservatives have long desired to dismantle and repeal the ACA writ large. In the latest attack, a group of conservative attorneys general are arguing in Texas v. United States that the ACA’s individual mandate is unconstitutional following the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017—and therefore, that the entire ACA is no longer valid.39 A decision from the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the case and the Supreme Court’s decision to hear it in the upcoming term have created uncertainty about the future of the ACA and the guaranteed benefits and protections the law affords.40 Additionally, the Trump administration has promulgated regulations to expand access to limited health plans. These include association health plans that do not have to cover EHBs and short-term plans that are not required to comply with EHBs; do not cover women’s preventive services; and are permitted to engage in discriminatory pricing, among other practices.41

- Attempts to undermine the ACA’s birth control benefit. The Trump administration and various organizations have actively undermined the ACA’s requirement that most health care plans cover birth control. In November 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) finalized rules that seek to exempt a broad swath of employers, universities, and insurers from adhering to the ACA’s birth control requirement if they claim a religious or moral objection.42 Although the rules were initially enjoined nationwide by lower courts, the Trump administration and various religious institutions appealed their cases to the U.S. Supreme Court. In July 2020, the court ruled to uphold the rules, paving the way for people’s access to birth control to be effectively stripped away.43 However, the Pennsylvania attorney general has vowed to continue the litigation, leaving the future of the rules uncertain.44

- Attempts to limit abortion coverage provided in the ACA marketplaces. The administration issued a final federal regulation in December 2019 that could have led private insurers nationwide to eliminate abortion coverage from their health plans. The rule required insurers to send consumers a separate bill for abortion services, which could dramatically increase administrative and operational costs for insurers and lead to significant confusion among consumers.45 However, a federal district court found that the rule violated both the ACA and the Administrative Procedure Act and issued a nationwide injunction, temporarily blocking the rule from going into effect.46

- Attempts to eliminate ACA nondiscrimination protections. In 2016, the Obama administration issued a final rule on the Health Care Rights Law that interpreted sex discrimination as inclusive of discrimination on the basis of gender identity, sex stereotyping, and termination of pregnancy.47 In June 2020, the HHS’ Office for Civil Rights issued its own final rule reinterpreting Section 1557 to, among other provisions, eliminate protections against discrimination based on gender identity and termination of pregnancy.48 The validity of this rule is thrown further into question by a recent Supreme Court decision, handed down just days after the final rule was issued, in a Title VII employment discrimination case in which the court found that employment discrimination on the basis of sex also extended to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.49

- Attempts to undermine the nation’s only federal family planning program, Title X. The Trump administration has also taken aim at family planning providers, undermining the integrity of the program. In March 2019, the Trump administration finalized its domestic gag rule that would bar Title X grantees from referring patients to abortion providers; allow providers participating in the program to withhold information and counseling regarding abortion; and require the physical separation of abortion services from all other health services.50 Grantees that do not comply risk losing their federal funding.51 Given that abortion already cannot be covered by Title X funds, the rule ultimately affects people’s ability to access reproductive health supplies, such as contraceptives and lifesaving preventive services such as cervical cancer screenings, HIV testing, and diabetes screenings. While litigation challenging the rules is pending, the rules are currently being implemented nationwide. As a result, dozens of Title X grantees—including the largest recipient, Planned Parenthood—have left the program’s network, and the network’s capacity has been reduced by Currently, more than 1.6 million women may be unable to access vital family planning services as a result of the new rules.52

- Targeting family planning providers in Medicaid. In addition to implementing a targeted attack against family planning providers in the Title X program, the Trump administration has targeted providers in the Medicaid program. The Medicaid statute outlines clear protections for people accessing family planning services and supplies, including a “free choice of provider” provision stipulating that a woman must be able to obtain family planning services with the provider of her choice without limitation.53 Unfortunately, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) rescinded 2016 guidance reaffirming this provision,54 and in January 2020, approved a Section 1115 waiver filed by Texas that will permit the state to exclude family planning providers from its Medicaid program.55 This policy change comes in addition to CMS allowing several states to impose work requirements and signaling that it will approve waivers to transform states’ Medicaid programs from entitlement programs to block grants or per capita caps.56 Each of these policies undermines the integrity of the Medicaid program and could limit enrollees’ access to the providers and services they want and need.

All of these policies and actions deliberately target reproductive health care and seek to exclude family planning services and providers from essential health care programs. While no one bill would solve all of the barriers impeding true access to reproductive health services—which include targeted abortion provider laws,57 family planning provider deserts,58 limits to providers’ scope of practice,59 and the stigma associated with reproductive health care60—universal coverage proposals, such as Medicare Extra, have the potential to expand reproductive health services beyond current and historical levels.

How Medicare Extra addresses reproductive health care

Medicare Extra is an enhanced Medicare plan that would be available to all lawfully present individuals in the United States. Employers could choose to sponsor Medicare Extra, and employees could choose Medicare Extra over employer-sponsored private insurance. Specifically, individuals with coverage through employer-sponsored insurance, the Federal Employees Health Benefits program, Medicare, TRICARE, or Veterans Affairs medical care could decide to either opt into Medicare Extra or remain on their current plans.61 The proposal would automatically enroll certain populations into the newly created program, including uninsured individuals, Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollees, and individuals who purchased insurance through the marketplace, as well as newborns and people who are 65 or older. People eligible for the Indian Health Service could also supplement their coverage with Medicare Extra. The framework also considers efforts toward comprehensive immigration reform, and coverage would be available to all lawfully present individuals.62

A study CAP commissioned from Avalere Health, an independent consulting firm that specializes in modeling health policy proposals, found that Medicare Extra would achieve universal coverage within three years by covering 35 million uninsured individuals.63 While 121 million employees are projected to choose to retain their current plans, Avalere estimates that 18 million employees would switch to Medicare Extra and an additional 9 million employees of small businesses that choose not to offer their own coverage would enroll in Medicare Extra.64

In addition to increasing coverage nationwide, Medicare Extra includes benefits that would enhance health care access, including access to reproductive care.65 These include:

- Benefits such as maternity, newborn, and reproductive health care. Medicare Extra would provide comprehensive benefits, including maternity, newborn, and reproductive health care as well as primary and free preventive care. Additionally, Medicare Extra would include other important services for people of reproductive age, such as coverage of prescription drugs and medical devices. The program would maintain coverage of the early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services benefit for young people, which is currently available to Medicaid recipients under the age of 21.

- Prohibition against discrimination. Medicare Extra would only allow premiums to vary based on age and health status, prohibiting adjustments based on preexisting conditions, such as pregnancy or gender and gender identity.

- Increased provider access. Individuals enrolled in Medicare Extra would have a free choice of provider, preserving the protection contained in the Medicaid statute. Additionally, the reimbursement rates that some providers would receive would increase and, as a result, the availability of providers for certain populations would increase due to expanded network participation in those communities. Medicare Extra would offer reimbursement rates that are higher than current Medicaid and Medicare rates—a key consideration for the family planning providers that serve more people with low-incomes who are enrolled in public insurance programs.66

- Lower out-of-pocket costs. Medicare Extra would reduce out-of-pocket costs, increasing access to coverage generally and reproductive health services specifically. It is estimated that Medicare Extra enrollees who were previously enrolled in Medicare, employer-sponsored insurance, or the individual market would all have lower premiums, and people who remain covered by their employer-sponsored insurance would also see lower premiums.67 Medicare Extra premiums would vary by income: Families with incomes up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) would pay no premiums; for families with incomes between 150 and 500 percent of the FPL, premiums would range from 0 to 10 percent of their income; and for families with incomes of 500 percent of the FPL or greater, premiums would be capped at 10 percent of income.68 Medicare Extra would also negotiate the prices of prescription drugs, medical devices, and durable medical equipment in order to lower costs and expand access.

Medicare Extra would achieve universal coverage while maintaining employees’ choice of plan. It presents a framework under which details can be adjusted as necessary for legislation but enshrines access to comprehensive reproductive health benefits. People who have historically been neglected in the health care system—including people of reproductive age, people of color, and people with low incomes—would be among the communities to benefit most from these coverage expansions, cost reductions, and comprehensive benefits.

Universal coverage proposals in the 116th Congress

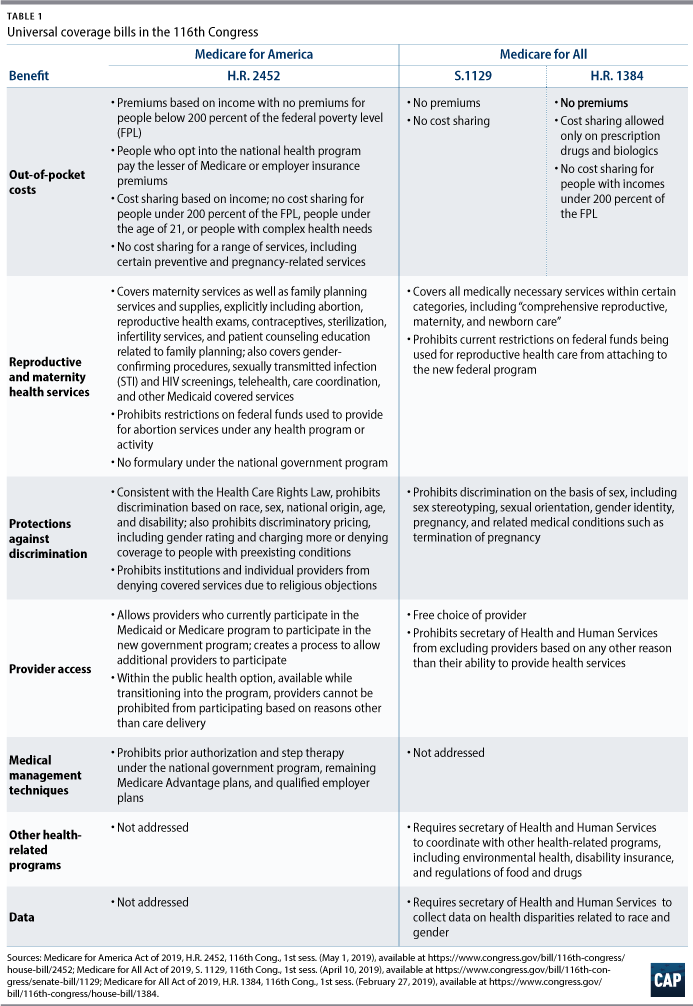

As noted above, there is proposed legislation currently in Congress that utilizes CAP’s Medicare Extra framework to create a national government health program. The following section examines proposals for federal programs through the lens of expanding reproductive health access, comparing Medicare for America with two other bills currently in Congress.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) have introduced bills in the Senate and House, respectively—both titled the Medicare for All Act of 2019—that seek to create a single-payer system with a national government-run health program.69 Reps. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) and Jane Schakowsky’s (D-IL) Medicare for America legislation, which uses CAP’s Medicare Extra framework, would also create a government-run national health program. However, this legislation maintains the existing Medicare program and the employer-sponsored insurance program.70 Individuals who have employer-sponsored insurance could remain covered by their current plan or enroll in the national health insurance program.71 Eligibility for each of the proposals would be limited to U.S. residents, as defined by the secretary of Health and Human Services, but Medicare for America requires the secretary’s definition to include lawfully present immigrants and immigrants eligible for emergency Medicaid services.

The Medicare for America and the Medicare for All legislative proposals are designed differently, including in the extent to which they maintain people’s current health care plans, and will subsequently have varying impacts on reproductive health access. Yet despite these differences, each of the proposed bills has the potential to significantly expand coverage of reproductive health services.

Medicare for America provides coverage for family planning services and supplies, explicitly covering abortion, gender-affirming treatment, wigs for medical care, and infertility treatment, among other services. It would allow federal funds to be used to cover abortion.72 The legislation allows income-related cost-sharing but does not allow cost-sharing for certain services, including preventive services, pregnancy-related services, and services for people living with HIV.73 Medicare for America would allow providers who currently participate in the Medicaid or Medicare programs to participate in the new government program and creates a process allowing additional providers to participate as well.74 Furthermore, Medicare for America would prohibit the government program, and the transitional public option, from excluding providers for reasons other than their ability to deliver covered services. As described above, this practice has in the past few years resulted in family planning providers being excluded from Title X and Medicaid programs.75 Finally, the legislation seeks to maintain the ACA’s Health Care Rights Law prohibiting discrimination based on sex, race, national origin, age, and disability, as well as maintain prohibitions against gender rating, discriminatory pricing, and exclusions based on preexisting conditions.76

Medicare for All would require coverage of “comprehensive reproductive, maternity, and newborn care”; maintain a prohibition against cost-sharing on preventive drugs; and prohibit current restrictions on federal funds that are used for reproductive health care.77 Additionally, both Medicare for All proposals guarantee coverage for all U.S. residents, as defined by the HHS secretary. Both the Senate and House bills also ensure that participants enrolled in the government program have a free choice of provider and prohibit the government from excluding qualified providers.78 The bills expand the ACA’s Health Care Rights Law to include explicit prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of sex—including sex stereotyping, sexual orientation, gender identity, pregnancy, and related medical conditions, including termination of pregnancy.79 The Senate’s Medicare for All bill has no cost-sharing except for prescription drugs and biologics,80 while the House’s Medicare for All bill would not impose cost-sharing on covered benefits.81

In short, both the Medicare for America and the Medicare for All bills could greatly expand access to reproductive health services. Each of the bills would eliminate or reduce the applicability of federal restrictions on abortion coverage and, at a minimum, maintain current coverage of contraceptives and prohibitions against gender discrimination. The bills would also expand coverage to more people and reduce out-of-pocket spending, thereby increasing access to reproductive health services.

Conclusion

Reproductive health care is, and should be treated as, health care—meaning that it should be embedded in the health care system with meaningful access for all. True bodily autonomy can never be achieved unless people are able to access the services they want and need without limitations or barriers. A move to universal coverage would mark the first time that reproductive health care has been truly embedded into the health care system and would eliminate many limitations on reproductive health care. Medicare Extra, in particular, offers an opportunity to achieve universal coverage and improve access to reproductive care while maintaining a pathway for millions of people to choose to maintain their current coverage.

About the authors

Jamille Fields Allsbrook is the director of women’s health and rights with the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress.

Osub Ahmed is a senior policy analyst for women’s health and rights at the Center.