This year marks the 40th anniversary of Supplemental Security Income. Signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1972, Supplemental Security provides basic income supplements to the elderly and to people with severe disabilities. This brief focuses on the largely unheralded role Supplemental Security has played in improving economic security and opportunity for children with severe disabilities, while at the same time reducing costly and harmful institutionalization of children.

Supplemental Security is a central pillar of our current system of family-centered care for children with severe disabilities. Other core pillars include Medicaid and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. In this system, the primary responsibility for the well-being of a disabled child rests with the child’s parents and family. Together, these supports play a fundamental role in making it possible for children with disabilities to live at home with their families and in their communities.

As detailed in this brief, Supplemental Security is an effective support for children with severe disabilities and their families. Research shows that Supplemental Security:

- Reduces costly and harmful institutionalization of children with severe disabilities by supporting family-centered care

- Reduces poverty and increases economic security by offsetting some of the extra costs and lost parental income associated with raising a child with a severe disability

- Supports work and education for parents and youth

- Reduces financial and other stressors that can adversely affect parental well-being and can lead to separation or divorce

- Serves as a critically important complement to other services provided to children with disabilities

- Provides initial disability determinations that are extensive and highly accurate

Supplemental Security should be maintained and strengthened to further increase economic security and opportunity for children and youth with disabilities. As recommended in this brief, this includes enhancing and promoting support for work and education; ensuring that the Social Security Administration has the resources it needs to conduct eligibility reviews so that Supplemental Security is limited to children who continue to meet medical eligibility criteria; and strengthening the profamily character of Supplemental Security.

Certain misguided proposals would disempower parents and put disabled children at a much greater risk of losing both a secure home environment and the opportunities for economic, social, and familial inclusion. These include cutting Supplemental Security by converting it to a block grant to states rather than a direct support to families, as well as other policies that would result in state micromanagement of parents’ decisions regarding how to care for their disabled children.

Who receives Supplemental Security Income?

Disability is a complex and evolving concept. In the most general sense, a disability is a health condition that significantly limits a person’s activity or restricts their participation when compared to individuals without a similar health condition. In the United States, about 6.6 million—or 9 percent—of school-age children have activity limitations that result from one or more chronic health conditions. Despite that being the case, only about 1.3 million—or 1.6 percent—of U.S. children receive Supplemental Security Income benefits. The vast majority of children with disabilities do not qualify for Supplemental Security either because their disabilities are not severe enough to meet the Social Security Administration’s strict standards or their families do not meet the program’s financial eligibility criteria.

Under the Social Security Administration’s definition of childhood disability, a child may qualify for Supplemental Security if she or he has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that results in marked and severe functional limitations and if she or he lives in a household with very low-income and less than $3,000 in assets. According to a 2012 Government Accountability Office report, the Social Security Administration has consistently denied a majority of children’s application for Supplemental Security over the past decade, using this stringent definition of disability.

How does the Supplemental Security help children with severe disabilities and their families?

Will Bentley, 10, lives in Covington, Kentucky, with his parents and sister. Nearly from birth, his parents knew something was wrong. He was slow in learning to speak and learned to sign so that he could communicate. He had frequent, violent seizures. An MRI eventually showed lesions on his brain. He struggles with anxiety and has memory problems. His mother Katie was forced to shut down her small business so that she could stay home with Will, whose care became a full-time job. Katie said, “I surrendered my career so that Will’s needs were met. SSI allows us to focus on what Will needs … At one time, Will was unable to do anything for himself. He could not even feed himself. Now he can read and zip his own jacket. For a parent with a child with a disability, the support that comes from SSI is a dream come true.”

Up until the 1960s, parents often placed children with severe disabilities into institutions. According to a public opinion survey conducted by the Minnesota Governor’s Council on Development Disabilities in 1962, 71 percent of the public said that people with development disabilities should be cared for in institutions rather than at home. Since then, as discussed in greater detail later in this brief, American attitudes have changed, and we have shifted away from institutional care to a system of family-centered care for children with disabilities. Under this system, we expect parents to care for children with disabilities at home, while providing them with necessary supports and services.

Supplemental Security serves as a central pillar of family-centered care. The modest income supplements provided by the program help families with very limited incomes and resources in the following ways:

- Provides basic necessities to care for a child with a disability at home instead of in an institution or another, more restrictive setting

- Meets the additional costs of raising a child with a physical or mental disability

- Replaces some of the family income lost when a parent (or parents) must stay home or reduce their hours to care for the child

- Assists in providing disabled children with a stable, secure home environment and the opportunity for integration into community life, including school as children and work as adults

For children who apply for Supplemental Security and are found eligible by Social Security Administration disability examiners, the income supplement that the program provides is modest. The maximum monthly supplement in 2012 is $698, an amount that amounts to about three-quarters of the monthly poverty threshold for an individual. Between one-third and one-half of children with severe disabilities receiving Supplemental Security have family incomes below the federal poverty line. It should be noted that, as with the poverty line, the Supplemental Security benefit has been adjusted for inflation over time but not for the increase in mainstream living standards.

For many families with a disabled child, Supplemental Security acts as a work support. In December 2010, despite near-record-high unemployment, some 41 percent of children receiving Supplemental Security lived with an employed parent. Just a decade earlier, when the unemployment rate was half of the current rate, most children receiving Supplemental Security lived with an employed parent. For disabled children living with a working parent, the supplemental income amount is reduced by about half of parents’ earnings (or nearly all of other income). Reducing the benefit by half, rather than all, of parents’ earnings helps limit the extent to which work is penalized as a result of means-testing.

A record of success

Supplemental Security replaced a patchwork of existing federal-state programs of aid to the aged, blind, and disabled. In his signing statement, President Nixon noted that people receiving benefits under these programs were “subject to great inequities and considerable red tape inherent in the present system of varying State programs with different benefits, eligibility standards, and rules.” A federal study of Supplemental Security’s implementation found that “the quality of life of the aged and disabled who are poor has improved greatly since they were transferred to [Supplemental Security] from former state programs.”

“My family would literally be homeless without SSI. I am the mother of Tyler and Noah, 5-year-old autistic twins. Both have severe symptoms—one is nonverbal and engages in typical autism behaviors like flapping his arms, spinning, and throwing tantrums; the other is verbal but has severe anxiety, intestinal problems, and sensory problems. Raising not one but two children with a severe disability took a toll on our marriage. I am now separated from my husband and right now our only dependable sources of income are food stamps and SSI. I want to work, but jobs with the flexibility I need to provide for my sons are hard to come by … SSI makes it possible for me to put a roof over my family’s head in the meantime.” —Rhonda Roberts, Eglin, Texas

Based on research examining how the program works for children with severe disabilities, we know that Supplemental Security:

- Reduces the costly and harmful institutionalization of children with disabilities: As recently as the 1960s, school-age children with disabilities commonly lived in institutions. With the passage of Supplemental Security, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and other landmark legislation, the number of children with disabilities living in institutions has steadily declined in the years since. In 2010 only about 1,000 children and youth (ages 0–21) with intellectual or developmental disabilities lived in state institutions. Institutional care is extremely costly. In 2010 the average monthly cost of state-institutional care was $16,200—more than 27 times the average Supplemental Security monthly benefit amount for a disabled child that year.

- Reduces poverty and increases economic security: Supplement Security increases the economic security of families caring for disabled children. Economists Mark Duggan and Melissa Schettini Kearney found that once families with disabled children start receiving Supplemental Security, their overall household income increases by 20 percent on average, and the likelihood of having income below the federal poverty line decreases by about 11 percent. At the same time, the amount of household income derived from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families declines.

- Supports and encourages work and education for parents and disabled youth: As mentioned above, Supplemental Security plays an important role as a work- and education-support program for parents of disabled children and for youth with disabilities. Although many parents of severely disabled children need to limit employment to focus on their children’s daily needs, Duggan and Kearney have found that receiving Supplemental Security does not reduce parental employment. Duggan and Kearney also found that the average earnings of households with children receiving Supplemental Security were about twice as high as the average earnings of households with children receiving Temporary Assistance to Needy Families benefits. As discussed later in greater detail, this is due in part to the incentives Supplemental Security provides for employment and education.

- Complements other services and supports provided to children with disabilities: The income support provided by Supplemental Security is a critical complement to other programs providing health insurance, supportive services, and health insurance. In addition to special health care needs, which often receive the greatest attention in discussions of how best to support children with disabilities, these children also have other basic needs that must be met, including food, shelter, and education. As the Committee on Childhood Disability explained in a 1996 report requested by Congress, one of the strengths of Supplemental Security is that it empowers parents to make decisions about how best to meet these needs. Social science research suggests that empowering parents in this way improves child well-being. According to distinguished policy researcher Greg Duncan, who has synthesized research in this area, “The weight of the evidence from research suggests that increases in income for poor families are causally related to improvements in children’s outcomes.”

- Assesses eligibility using a thorough and highly accurate disability determination process: Disability examiners follow what the Social Security Administration calls the “whole child approach,” relying on an array of sources to assess eligibility for benefits—such as medical records, school records, teacher and parent assessments, and prescribed treatment and medications. According to a 2012 Government Accountability Office report on Supplemental Security for disabled children, disability examiners generally relied on four to five sources as support for their decisions in 2010, with the most frequent source being the opinion of a treating medical provider. This thorough review ensures that the initial disability determination process is highly reliable: The Social Security Administration’s Office of Quality Performance reports a net accuracy rate of more than 97 percent. As we discuss in greater detail later in this brief, however, timely reviews of children’s disability status—known as continuing disability reviews—are critical to ensuring that disabled children receive benefits only for the period during which they remain eligible. The Social Security Administration needs adequate administrative funding to eliminate the current backlog of continuing disability reviews and to perform timely reviews going forward.

Recommendations for strengthening Supplemental Security program for children with disabilities

As discussed earlier, Supplemental Security is tremendously effective. It can and should be strengthened in a number of ways to further increase economic security and opportunity for children with disabilities and their families. Let’s turn to these recommended program improvements now.

Enhance and promote work and education incentives

As currently structured, Supplemental Security contains an array of incentives for beneficiaries to pursue employment and education, including:

- The first $85 plus half of all remaining monthly earnings do not reduce Supplemental Security monthly benefits.

- For beneficiaries under age 22 who are regularly attending school, all earnings up to $1,640 per month (and a yearly maximum of $6,600) do not reduce Supplemental Security benefits.

- In most states, Medicaid coverage is continued if the child ceases to receive Supplemental Security due to earned income, so long as certain criteria are met.

- Young people can continue receiving Supplemental Security up to age 22 while they finish school and transition into special vocational rehabilitation programs.

Research by economic and policy researchers David Wittenberg and Pamela Loprest indicates that the vast majority of young people with disabilities receiving Supplemental Security may be unaware of the ways in which the program supports work and education. The researchers say that greater awareness about the program’s work and education supports could be achieved through enhanced and targeted outreach by the Social Security Administration, as well as individualized benefit counseling for disabled youth that would explain how the program can support their work and educational goals.

Improved outreach and counseling would be most logically achieved through existing structures such as the Work Incentives Planning and Assistance program and the Protection and Advocacy for Beneficiaries of Social Security program, both established as part of the Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999. Congress, however, has failed to reauthorize either the Work Incentives Planning and Assistance program or the Protection and Advocacy for Beneficiaries of Social Security program, leaving the future of these successful programs in doubt. Congress should act quickly to reauthorize both programs and ensure their full funding so that Supplemental Security beneficiaries—especially transition-age youth—have access to benefits counseling and support before and while they try work.

In addition, Supplemental Security’s work and education incentives should be further strengthened to more effectively support transition-age youth who are pursuing education or trying to obtain stable employment. The Social Security Administration’s innovative Youth in Transition Demonstration Initiative has provided extra supports to youth receiving Supplemental Security or Social Security Disability Income in seven local sites in the 2000s. Early results from a random assignment evaluation of the initiative suggest that some of the sites—particularly those providing fairly intensive employment services—have been successful at increasing the share of disabled youth with employment and earnings. Interestingly, these sites were successful at increasing employment at the same time that they modestly increased the amount of Supplemental Security received (for disabled youth who received extra supports compared to those who did not), in part due to demonstration rules that allowed them to earn more before losing benefits or having their benefits reduced.

Any consideration of ways to improve outcomes for youth receiving Supplemental Security—as well as youth who are terminated from Supplemental Security when they turn 18 and are reviewed under the adult disability standard—also needs to account for the dismal economic context in which young working- and middle-class people in general currently find themselves. The real average hourly wages of high-school graduates fell by 10 percent between 2000 and 2011. While the expansion of benefit programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit have helped to offset declining real wages for adults with children, youth under age 25 are ineligible for the tax credit unless they themselves have a child. This makes little sense, particularly for young people with disabilities struggling to obtain decent employment.

Expand access to vocational education and vocational rehabilitation for transition-age youth

State-run vocational education and rehabilitation programs offer tremendous value, providing individuals with disabilities training, skill development, and work experience. Simple commonsense reforms would enable transition-age youth with disabilities to enroll in such programs and prevent them from falling into a gap in services between high school and the adult world of work. For instance, enrollment in vocational education/rehabilitation programs is currently restricted to people with disabilities age 18 or older. Rather than exclude disabled children under age 18 from these programs, federal policy should promote a seamless transition from special education to vocational programs.

Additionally, many youth with disabilities currently spend significant periods of time on wait lists before receiving vocational education and rehabilitation services. Increased investment is urgently needed so that vocational education and rehabilitation programs’ capacity can more closely match the needs of the population.

Support and enhance innovation for improving employment and other outcomes for youth with disabilities

In addition to the Youth in Transition Demonstration Initiative described earlier, another demonstration effort, the PROMISE program—Promoting Readiness of Minors in SSI—was recently established to fund and evaluate pilot projects that aim to improve outcomes for youth who receive Supplemental Security and their families. Other recent pilot programs include the Opening Doors to the Future Project and the Transitional Employment Training Demonstration, both of which explore how to most effectively support improved outcomes for youth, through a more integrated, holistic approach to transition support.

Support should continue for these and other demonstration initiatives. As they demonstrate successful methods and/or reforms to Supplemental Security and other programs that support youth with disabilities, said successes should be incorporated into the relevant programs and scaled up for national impact with input from the disability community, as well as the disability advocacy community.

Provide the Social Security Administration with adequate funding to conduct timely continuing disability reviews

The Social Security Administration is required by law to conduct periodic continuing disability reviews to ensure that only those individuals who remain eligible for Supplemental Security continue to receive benefits. Congress has for a decade, however, failed to provide the Social Security Administration with the funding it needs to perform these reviews on a timely basis. Disability reviews are highly cost-effective, yielding an estimated $10 or more in savings for every $1 spent in conducting the review. Additional Social Security Administration program integrity funds were appropriated in 2011, representing a step in the right direction. Additional and ongoing targeted funding—at levels closer to those provided in the years 1996 to 2002—is needed, however, so that the agency can fulfill its statutory obligations in conducting on-time reviews where required.

Conduct further research to explore the value of outreach to families with disabled children

As discussed earlier, raising children with disabilities can translate into considerable hardship for families. In addition to financial and material hardship, parents often experience adverse health consequences, stress, and psychological distress. Sociologist Dennis Hogan has found that rates of divorce and separation are much higher for couples who give birth to children with disabilities than for other parents. The Social Security

Administration should fund research and possibly demonstration projects aimed at testing family-strengthening supports and/or determining whether and how Supplemental Security helps ease these burdens. If it does, targeted program outreach to families in hospital and clinical settings may be warranted. Research might also consider potential changes to the program to further support parental well-being and family stability.

Modernize Supplemental Security asset limits

As previously noted, individuals with disabilities must meet stringent financial eligibility requirements in order to qualify for Supplemental Security. When the program was enacted in 1972, disabled people with counted assets of more than $1,500 (for an individual) or $2,250 (for a couple or a child living with a parent) were excluded from coverage. These asset limits have barely moved since then—last increased in 1989—and today are just $2,000 and $3,000, respectively. If the limits had been adjusted annually for inflation since 1974, today they would be nearly $7,000 and $10,500, respectively. Supplemental Security’s extremely low asset limits are counterproductive and leave families unable to maintain precautionary savings for repairing a broken water heater, leaky roof, or other urgent, unforeseeable expenses. The asset limit should be increased to $10,000 and indexed for annual inflation to realign the asset policies with intended levels.

In addition, a sensible regulatory reform should be made to ensure that disabled children don’t lose Supplemental Security just because their families are in the process of losing their homes. As it stands now, the Social Security Administration does not count a home that a child’s family is living in toward the asset limits but does count the value of “nonresident property” as a resource. Disabled children whose families are forced to leave their homes during a foreclosure often end up losing Supplemental Security because it is treated as nonresident property. An exception should be made for properties in foreclosure.

Parents’ unemployment insurance and worker’s compensation benefits should be treated no differently than the earnings that they replace

As already noted, under current program rules, $85 plus half of a parent’s earnings are disregarded in determining whether a disabled child is eligible for Supplemental Security, as well as the amount of the supplement. If a parent is laid off, however, and receives unemployment insurance, there is no similar disregard. When a parent’s unemployment benefits are fully counted, the disabled child may end up being over the program’s income limit even though their overall income has fallen. As a result, the harm of parental unemployment may be compounded by the loss of Supplemental Security. The same rules also apply to worker’s compensation. In 1995 the National Commission on Childhood Disability, an advisory body established by Congress, recommended treating these benefits as earned income so that children with severe disabilities do not lose Supplemental Security when their parents become injured on the job or laid off. Congress has yet to act on this recommendation. Unemployment insurance and worker’s compensation are earned benefits that should be treated no differently from the earnings they are intended to replace.

Conclusion

Supplemental Security is an effective support for children with severe disabilities and their parents. It increases economic security by offsetting some of the extra costs and loss of parental income that accompany the responsibility of raising a child with a severe disability—without having negative effects on parental employment. Supplemental Security should be maintained and strengthened to further increase economic security and opportunity for children and youth with disabilities and to ensure the continued success of family-centered care.

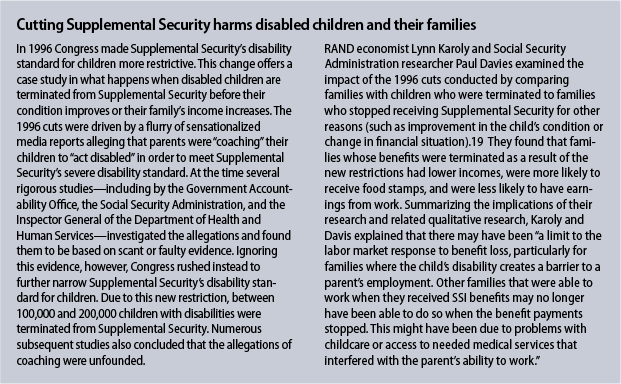

Rebecca Vallas is a staff attorney at Community Legal Services. Shawn Fremstad is a senior research associate at the Center for Economic Policy Research and a consultant to several national nonprofits on federal policy issues.