On May 21, 2013, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved the bipartisan “Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013” by a vote of 13 to 5. In addition to strengthening our border and creating a sensible plan for future immigration, the bill enables the 11 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States to earn citizenship over time. Legalizing the undocumented population would lead to significant economic gains for all Americans by increasing productivity, wages, and tax revenue and by supporting the creation of new jobs through the growth in consumption and business creation.

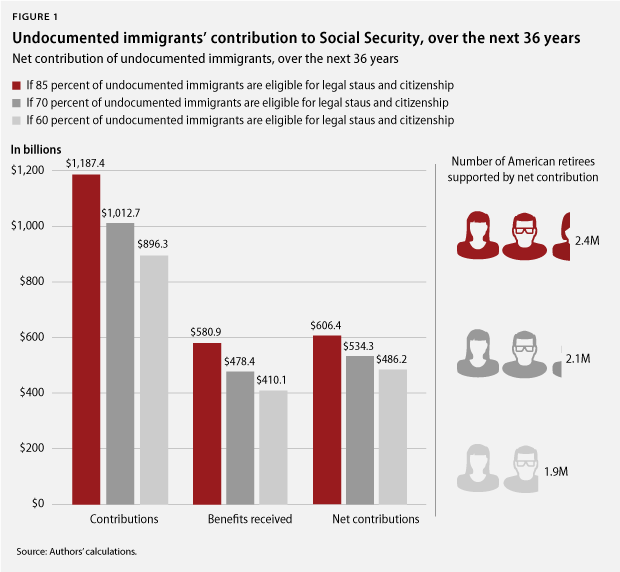

In this issue brief, we analyze the impact on the Social Security system of legalizing the undocumented population. Despite the wide body of research that details the economic gains that come with immigration reform, some lawmakers still question the long-term impact of earned legalization on social programs such as Social Security. Bringing undocumented immigrants out of the shadows and allowing them to participate fully in our economy and society will further strengthen many of our country’s social services, both in the immediate future and in the long run. The findings from this brief are clear: If undocumented immigrants acquire legal status and citizenship, they will contribute far more to the Social Security system than they will take out and will strengthen the solvency of Social Security over the next 36 years. (see Figure 1)

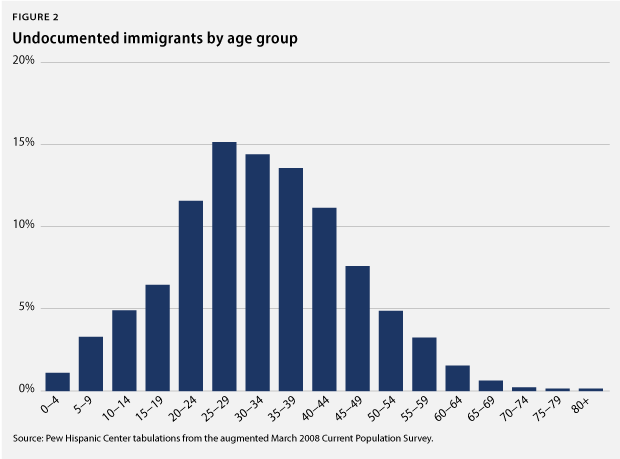

The analysis below estimates the net contribution to Social Security—taxes paid into the system minus benefits received—of formerly undocumented immigrants after legalization. This year the first of the Baby Boomers will turn 67 years old and be eligible to receive full Social Security benefits. Over the next 36 years, these Boomers will present a financial challenge to the Social Security system, which can be alleviated in part by the contributions of the relatively young undocumented immigrant population, whose adult mean age is only 36. We examine the net contributions over this 36-year time period, when Social Security will be the most affected by Boomers’ retirements. While legalized immigrants will ultimately be eligible for Social Security upon retirement, the vast majority of them will not receive any benefits until the Baby Boomer generation—and the major strain on the system—has passed.

We estimate the net contributions of legalized immigrants under three scenarios. The first scenario assumes that 85 percent of the undocumented population will be eligible to apply for legal status and citizenship; the second assumes 70 percent will be eligible to apply; and the third assumes only 60 percent will be eligible to apply. We conduct this analysis across three different scenarios to illustrate how the net contribution to the Social Security system would be substantially reduced if the number of people eligible for legal status and citizenship were curtailed.

The evidence is clear that the newly legalized will have a positive effect on the solvency of the Social Security system. As these three scenarios illustrate, as fewer undocumented immigrants are eligible to apply for legalization and citizenship, the gains to Social Security solvency decline dramatically. On top of the many other positive impacts of bringing the undocumented out of the shadows, these results indicate that providing legal status and a pathway to citizenship to the 11 million undocumented immigrants currently in this country would have a sizeable impact on the ability to provide full pensions to the Baby Boomers in the years to come.

Current state and financial strains of Social Security

Social Security is a vital system in which all Americans have a vested interest. Across the country, more than 37 million retired workers currently receive and rely upon Social Security benefits to sustain their financial security. These benefits account for 34 percent of the income for the U.S. population ages 65 and older. Currently, the Social Security Administration’s income (tax revenues and interest on investments) is more than able to cover the costs of benefits paid out. But the Social Security trustees expect that the system will face financial challenges over the next few decades, as the U.S. population ages and as the largest generation in America’s history, the Baby Boomers, retires and starts drawing benefits.

This year the first of the Baby Boomers—those who were born between 1946 and 1964—will turn 67 and be eligible to receive full Social Security retirement benefits. The last of the Baby Boomers will not turn 67 until 2031, meaning that the Boomers will be collecting benefits for roughly the next 36 years, from 2013 through 2049 (assuming that, on average, people receive benefits for 18 years). The retirement of Baby Boomers over the next few decades explains why the number of workers paying Social Security taxes per beneficiary will fall from a ratio of 2.8 workers to beneficiary in 2013 to 2.1 workers by 2050.

Although the Social Security system will face mounting financial strains over the coming decades, the financial problems will largely cease growing as Baby Boomers exit the system and stop collecting benefits. In other words, just as demographic changes are creating financial instability for the system, demographic changes too will be a large part of the solution: As Baby Boomers die, the system will begin to stabilize. To be sure, there are policies that could relieve the financial burden brought on by the retirement of Boomers—revenues could be increased and/or benefit levels could be lowered. But our country does not need to wait until Boomers exit the system to see relief, and there are ways to alleviate some of the financial pressure without altering the system. Right now there are millions of undocumented workers in our country who are contributing far less into the system than they otherwise could.

In the following sections, we examine the current contributions of unauthorized immigrants into the Social Security system and their potential future contributions and benefits received after legalization to illustrate the positive effect of legalization on the long-term solvency of the system.

Current contributions of undocumented immigrants to Social Security

The Social Security Administration has long identified the positive contributions undocumented immigrants have made to Social Security. Although undocumented immigrants are not legally allowed to work in the United States, roughly 3 million of the 8 million undocumented workers in the United States pay Social Security taxes. In 2010 alone the Social Security Administration estimates that a net $12 billion was paid in taxes on the earnings of undocumented workers.

These workers pay payroll taxes by either using someone else’s Social Security card or by using a false name and Social Security number. Often, the information a given worker uses does not match the Social Security Administration’s database of names and corresponding Social Security numbers. The Social Security Administration needs to know who is paying how much in taxes in order to calculate the level of benefits a worker will receive upon retirement. When a mismatch occurs, the administration cannot credit these taxes to any worker, so it holds the information on the tax contribution in a separate file—called the Earnings Suspense File—until the discrepancy is resolved. To be clear, some of the information in this file is the result of contributions by legally authorized workers who end up drawing benefits. If a person gets married and changes his or her name but fails to notify the administration, for example, then there may be a mismatch in the system, and the taxes paid by this worker are not credited to him or her until the mismatch is rectified.

The Earnings Suspense File, while not actually a fund of money, represents in part how much undocumented immigrants have contributed over the years. But these same immigrants will never be credited for these contributions—nor receive benefits from them—since they are barred from receiving Social Security. It is estimated that the file contains information on roughly $1 trillion worth of tax contributions.

Future contributions of undocumented immigrants

Undocumented immigrants have already made significant contributions to the Social Security system and in doing so have improved its solvency. But with only 3 million of the 8 million unauthorized workers paying Social Security taxes, undocumented immigrants collectively are contributing far below their potential. Immigration reform would lead to greater contributions to the Social Security system for two primary reasons.

First, providing legal status and an earned pathway to citizenship would bring workers out of the underground economy and allow them to work legally and contribute to the Social Security system. Currently, only 37 percent of undocumented workers pay Social Security payroll taxes. This means that the United States stands to see millions of additional workers going “on the books” and contributing to the system through payroll taxes if undocumented immigrants are able to work legally.

Second, undocumented workers’ wages increase after legalization, and so too will the taxes paid on their earnings. Research by the Department of Labor concluded that providing legal status to undocumented immigrants increased their earnings by 15 percent. Further research has found that becoming a citizen brings an additional 10 percent increase in earnings.

Increased contributions by all American workersIt is not only the undocumented that would contribute more to the system as a result of comprehensive immigration reform; native-born Americans would also contribute more. Previous research has shown that the earnings of native-born workers will increase if undocumented immigrants are provided legal status and citizenship. Nationally, the cumulative increase in all Americans’ earnings would increase by $470 billion over the next 10 years. Similarly, economists have found that the wages of native-born workers increase by 0.6 percent as new immigrants enter the country. Immigration reform would therefore also increase all Americans’ contributions to Social Security due to increased earnings. (While we have not added the increased contributions from native-born workers to our calculations of the net contributions of legalized immigrants, it is important to note that our estimates would be even higher if these figures were added.)

Long-term net contributions of legalized immigrants

Providing legal status and citizenship to the undocumented population will no doubt allow these aspiring Americans to collect benefits upon retirement—similar to any other American who works and pays into the system for 10 years. But this does not necessarily mean that undocumented immigrants will be a drain on the system. Policymakers should focus less on whether this population will eventually collect benefits and instead place their attention on when these individuals will retire.

According to the Pew Research Center, the average age of adult undocumented immigrants is 36 years old, and for the whole population it is even younger. This means that most undocumented immigrants will be working and paying into the system for more than 30 years before they can receive full retirement benefits. To be sure, there are some undocumented immigrants who will reach the age of retirement before all of the Baby Boomers have passed through the system. But this is only a small percentage of the total population. The vast majority will be paying into the system, rather than taking from it, during the period of greatest strain.

In our analysis, we projected the earnings of the undocumented population over the next 36 years and estimated their net contributions to the system for each age group if they acquire legal status and citizenship under three scenarios. In this way, we include even those who will be receiving benefits within the timeframe of our analysis to make the most accurate assessment of net benefits possible.

The first scenario assumes that 85 percent of the 10.6 million undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States before December 31, 2011, are eligible to apply for legalization and citizenship. Under the Senate Gang of 8’s bill, and likely any immigration reform, there are limiting criteria such as criminal convictions that make some individuals ineligible to complete the pathway to earned citizenship. We use an 85 percent eligibility rate in this first—and most realistic—scenario to account for the fact that some individuals may be ineligible to apply for legal status and citizenship.

Other issues, especially future amendments to the immigration bill, could end up restricting eligibility for legalization even further. When the Gang of 8’s bill went through the mark-up process in the Senate Judiciary Committee, there were amendments that, if passed, would bar many undocumented immigrants from applying for legal status and citizenship. One amendment, for example, would prohibit an undocumented immigrant from receiving legal status if his or her income was below 400 percent of the federal poverty line. This amendment would ultimately limit the number of people who would be eligible to apply for legal status and citizenship.

In order to analyze the impact that limiting the number of people who acquire legal status and citizenship would have on the net contribution of legalized immigrants to Social Security, we conducted our analysis under two additional scenarios. The second assumed that only 70 percent of the undocumented population would be eligible to earn citizenship, and the third scenario used a 60 percent eligibility rate.

Across all three scenarios, we determined that over the next 36 years, undocumented immigrants would contribute far more into the system than they would take out. But the net contribution declines as fewer immigrants are able to earn legal status and citizenship. These findings suggest that undocumented immigrants have the greatest positive impact on Social Security when the largest share possible of the undocumented population is able to come forward.

Under the first scenario, $1.2 trillion in Social Security taxes would be paid on the earnings of undocumented workers, while only $580.9 billion would be received in benefits. This leads to a net positive contribution of $606.4 billion over 36 years. Under the second scenario, $1 trillion in Social Security taxes would be paid on the earnings of undocumented workers, while only $478.4 billion would be received in benefits. This leads to a net positive contribution of $534.3 billion. Under the third scenario, $896.3 billion in Social Security taxes would be paid on undocumented workers’ earnings, while only $410.1 billion would be received in benefits, leading to a net positive contribution of $486.2 billion. If the more than $1 trillion already contributed to the Earnings Suspense File is added to the total contribution of the undocumented to the Social Security system, under the first scenario, the net contribution would be closer to between $1.6 trillion and $1.7 trillion.

Legalized immigrants would provide immediate relief to the Social Security system

Our analysis shows that undocumented immigrants would provide a significant net positive contribution to Social Security over the next 36 years, but legalization and citizenship would also alleviate much of the system’s fiscal burdens in the short term as well.

Our analysis estimates, for example, that the undocumented would contribute $22.2 billion in 2014 alone, reducing the projected gap between benefits paid and taxes received by more than 37 percent. And over the next 10 years, the net contributions would reduce this difference by 30 percent.

But these 10-year gains are not the peak of the undocumented immigrants’ contribution. As undocumented immigrants acquire citizenship and younger immigrants come of age and join the workforce, the net contributions made by the undocumented population will increase and continue to fund the retirement benefits of millions of Americans.

Currently, native-born beneficiaries who are ages 67 and older on average receive $13,994 in benefits each year. The $606.4 billion net contribution made by undocumented workers under the first scenario would fund a lifetime of Social Security benefits for 2.4 million native-born Americans. This is more than 6.5 percent of the 37 million Americans drawing Social Security retirement benefits. Under the second scenario, the net contribution would fund 2.1 million native-born Americans, or 5.7 percent of retired beneficiaries. And under the third scenario, the net contribution would fund the lifetime Social Security benefits for 1.9 million native-born Americans, or 5.1 percent of the 37 million Americans drawing retirement benefits.

What would the undocumented population’s contribution be in the absence

of immigration reform?The Social Security Administration estimates that 37 percent of undocumented workers currently pay into the Social Security system. In the absence of immigration reform, we could expect a similar rate of undocumented immigrants to continue to pay into the system. And since the unauthorized are barred from collecting Social Security, the benefits paid out would be nil. We can also calculate how much the undocumented would pay in taxes over the next 36 years in the absence of immigration reform. We found that the taxes paid on the earnings of undocumented immigrants, were they denied legal status and citizenship, would be $462.2 billion over the next 36 years. This is just a small share of the potential $1.2 trillion that could be contributed to the system over the next 36 years under immigration reform and significantly less than their net contribution under all three scenarios.

Conclusion

As the immigration debate moves forward, policymakers should keep in mind the economic benefits of providing an earned pathway toward legal status and citizenship for undocumented immigrants. If undocumented immigrants acquire this status, they will pay hundreds of billions of dollars more in Social Security taxes than they will receive in benefits over the next 36 years. These large net contributions will fund the retirement benefits of millions of Americans and a sizeable share of retirees, decades before the majority of undocumented immigrants ever collect a penny in benefits. Moreover, these reforms would improve the financial stability of the Social Security system during the very period in which it is expected to be the most strained. Our analysis also finds that limiting the number of undocumented immigrants able to acquire legal status and citizenship would significantly reduce their contribution to the solvency of the Social Security system and to the well-being of all Americans.

Adriana Kugler is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and full professor of public policy at Georgetown University. Robert Lynch is a Senior Fellow at the Center and the Everett E. Nuttle professor of economics at Washington College. Patrick Oakford is a Research Assistant at the Center in the Economic and Immigration Policy departments.

This study was made possible by the generous support of the JBP Foundation. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the JBP Foundation.

The authors would like to thank Philip E. Wolgin and the Immigration Policy team for all of their insight and helpful comments.

Appendix

Methodology

The calculations in this report draw upon the following data sets: the March 2012 Current Population Survey, or CPS; Pew Research Center’s estimates on the age profile of the undocumented immigrant population; and the Migration Policy Institute’s estimates on the age profile of undocumented immigrants who came to the United States before the age of 16.

Social Security contributions

For each age cohort, we estimate the cumulative Social Security contributions they will make from age 18 until they reach the age of 67. We applied the standard 12.4 percent Social Security tax rate to the estimated earnings for each cohort, which were calculated using the March 2012 CPS. Based on previous studies, we assumed that legalization would increase the earnings of undocumented immigrants by 15 percent and that the acquisition of citizenship would result in an addition 10 percent increase. We adjusted average earnings each year by an annual 1.13 percent wage increase as estimated by the Social Security trustees.

Under the Gang of 8’s bill, the DREAMers—undocumented immigrants who entered the country before the age of 16 and who have met a series of requirements such as graduating from high school or having a GED—are put on a faster pathway to citizenship. This means they would experience the 10 percent increase in their earnings sooner than those on the 13-year pathway to citizenship and subsequently contribute more to Social Security sooner. In our estimates, we therefore calculated the DREAMers’ future contributions separately from the larger undocumented immigrant population. After calculating each age cohort and the DREAMers’ contribution to Social Security over the next 36 years, we summed each age group to come to a total contribution for the population.

Social Security pension benefits

Similar to the calculations of contributions, we utilized the March 2012 CPS data to estimate benefits received for each age cohort by identifying the average benefit received by noncitizen immigrants who have been in the United States for the same number of years that a respective age cohort will work and would have lived legally in the United States before reaching the age of 67. We assumed that individuals will collect benefits for 18 years, which is the average length of time for which retirees collect pensions.

In practice, the Social Security Administration uses a detailed formula to calculate each retiree’s benefits. First, a beneficiary’s earnings over the 35 years in which they earned the most are indexed to account for changes in average wages in the country across those 35 years. Then the administration finds an average of the indexed earnings and applies a formula to this average to arrive at the monthly retirement benefits.

Our methodology captures the end result of the Social Security Administration’s formula by looking at the average Social Security benefit received by noncitizen immigrants in a given age cohort. We adjusted the average benefits received by each age cohort by the same annual 1.13 percent wage increase that we applied to the contribution side. Our methodology slightly overstates the benefits received because the Social Security Administration does not increase benefits received by the same amount in which real wages rise. When one compares our estimate of benefits received to the estimated amount of benefits received under a method that applies the Social Security Administration’s benefits formula to the undocumented population, the numbers are nearly identical. Under the first scenario, for example, we estimated that $580.9 billion would be received in benefits; under the Social Security Administration’s benefits formula, the benefits received under the same scenario would have been $575.4 billion. Our methodology therefore provides a more conservative estimate of the net contribution, given that it is likely overstating the benefits received.