In the past four years, states have enacted 231 restrictions on abortion care, severely limiting women’s access to this legal and safe procedure. Under the guise of protecting women’s health, state legislatures, particularly in the South and Midwest, have been actively introducing and passing bills that are neither evidence-based nor backed by science—effectively placing politicians in the consultation room with patients. For instance, there is only one clinic where abortion care is provided in each of the following four states: Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, and South Dakota. And while the courts have not yet made final rulings on Texas’ H.B. 2, a comprehensive package of restrictive abortion laws, women’s access to abortion care in Texas has already been severely curtailed. At the same time, the number of abortion providers and locations where abortion care is available has been steadily decreasing, and fewer clinicians are willing or able to deliver abortion care due to these new restrictions.

However, states have increasingly begun to introduce legislation that protects access to abortion care and, in some cases, expands access. California has been a leader in protecting and expanding access to abortion care. In 2002, the state passed a law that allows advanced-practice clinicians, or APCs—including nurse practitioners, or NPs, certified nurse midwives, or CNMs, and physician’s assistants, or PAs—to provide medication abortions. And in 2013, after rigorous study, evaluation, coalition building, and advocacy, the legislature passed a law to allow these health care professionals to provide aspiration abortions in the first trimester as well. The law went into effect on January 1, 2014. Other states should consider following California’s example by expanding abortion access rather than restricting it.

This issue brief will provide background on the need for additional states to pass legislation and implement policies allowing APCs to provide abortion care; an overview of the new policy; and an analysis of states where such legislation should be introduced.

The need for more abortion providers

The rate of abortions performed in 2011—16.9 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44, or 1.06 million abortions total—was the lowest since 1973, when abortion became legal. However, 1.7 percent of women of reproductive age in the United States continue to have abortions each year. One out of three women will have an abortion in her lifetime. Abortion is a common procedure, but it has become more difficult to access in recent years.

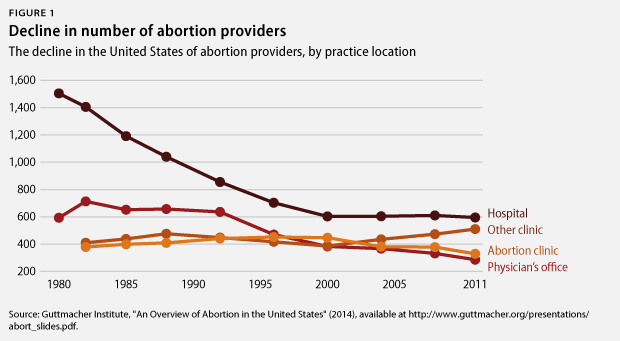

From 2010 to 2013, 54 health centers that provided abortions were shuttered or ceased to provide abortion care. As of 2011, 89 percent of U.S. counties did not have an abortion clinic, and 38 percent of American women live in these counties. In 2011, the number of abortion providers decreased by four percent from 1,793 in 2008 to 1,720. (see Figure 1) Women living in rural areas are disproportionately affected by a lack of access to abortion care. Reduced access to abortion care often results in delayed procedures, which can increase the cost of abortion care due to later-term and higher-risk procedures.

The current role of advanced-practice clinicians in providing abortion care

After the Supreme Court’s 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, multiple states passed laws that only allowed licensed physicians to provide abortion care. These laws were originally introduced and passed in order to protect women from unlicensed providers. However, this was also before there was a large number of APCs providing care and before their roles were codified into state law across the country. In the years since these restrictions were implemented, the number of APCs has increased, creating a group of potential abortion providers that continues to grow.

In 2013, there were 205,000 licensed NPs and 93,098 PAs nationwide. There were also 11,192 CNMs in 2014. APCs are geographically dispersed across the United States and many play a role in providing care to underserved populations. For example, grantees of the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s Health Center Program serve poor, uninsured, and rural patients in their clinics, and 14.6 percent of their full-time medical employees are APCs who make 36.6 percent of the clinical visits. APCs also have a prominent role in family planning services, making up 66 percent of the full-time clinical service providers in health centers that receive Title X family planning funding. Given their experience caring for the patients most in need, expanding APCs’ practice to include abortion could alleviate many of the constraints that American women face in accessing abortion providers.

Beyond abortion services, some policymakers have suggested that expanding APCs’ scope of practice could help fill the shortage of primary care providers in rural America. Research suggests that the quality of care provided by APCs is on par with or, in some circumstances, better than care from a physician. Expanding APCs’ scope of practice could also potentially reduce the cost of primary care as their billing rates for visits and medical procedures are usually lower than the rates of physicians. While these findings and recommendations address the lack of primary care providers, rural areas also have limited abortion resources. If expanded scopes of practice for APCs could improve the primary health care available in rural areas, they could also improve the availability of abortion services for this underserved population.

Determining who can and cannot provide abortion care

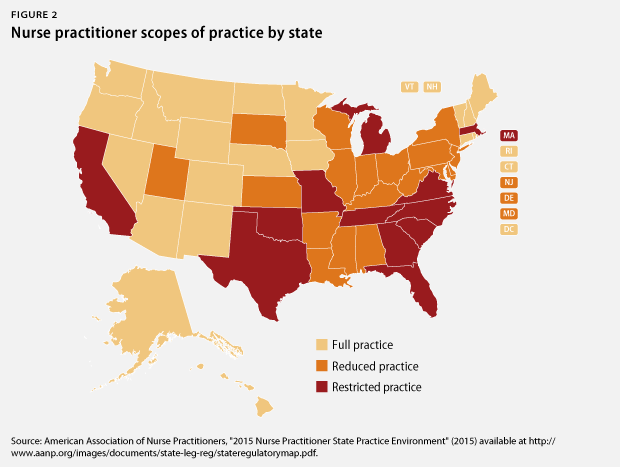

Scopes of practice define what types of care APCs, physicians, and other health care professionals can legally provide. They are defined and enforced by state legislatures and licensing boards through state practice acts. Professional organizations help clarify and define which procedures, practices, and competencies should be included in each profession’s scope of practice. While national professional organizations, such as the American Academy for Nurses Practitioners, share the same recommended competencies and standards with all states, scopes of practice for APCs vary widely from state to state. In some states, such as Massachusetts and California, NPs have restrictive practice acts and are required to have the supervision of a physician. However, in many rural states, such as Wyoming and Idaho, NPs have full practice authority to provide the health care outlined in their practice acts without supervision by another health care provider. (see Figure 2)

Scope of practice types

Full practice: NPs evaluate patients; make diagnoses; order and interpret tests; initiate and manage treatment; and prescribe medications without a physician or other health professional’s supervision.

Reduced practice: Some components of full practice can only be carried out by NPs under a collaborative agreement with another health professional, usually a medical doctor.

Restricted practice: Most or all components of full practice can only be carried out by NPs under a collaborative agreement with another health professional, usually a medical doctor.

Scopes of practice can be updated and revised by state licensing boards—for example, boards of nursing—through rulemaking and other administrative processes such as rulings by state attorneys general or state judicial rulings. These processes have been very successful in expanding medication abortion privileges for APCs. However, after analyzing the potential options to change the scopes of practice for abortion care in California, advocates determined that passing legislation would provide APC’s with “long-lasting legal protection and a secure environment in which to enter the aspiration abortion workforce.”

Scopes of practice can be updated and revised by state licensing boards—for example, boards of nursing—through rulemaking and other administrative processes such as rulings by state attorneys general or state judicial rulings. These processes have been very successful in expanding medication abortion privileges for APCs. However, after analyzing the potential options to change the scopes of practice for abortion care in California, advocates determined that passing legislation would provide APC’s with “long-lasting legal protection and a secure environment in which to enter the aspiration abortion workforce.”

The California example

California is the first and only state to successfully pass narrowly focused legislation adding first-trimester aspiration abortions to APC scopes of practice. More than 10 years ago, a committed group of academics, policy professionals, and advocates began an effort to expand abortion access for women in California. At the time, only physicians were allowed to perform aspiration abortions, and women in rural and underserved urban areas had inadequate access to abortion care as evidenced by more women requiring later abortions.

In order to prove that APCs could safely provide first-trimester aspiration abortions, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, or UCSF, conducted a multiyear, prospective, scientifically rigorous study in which APCs were trained and evaluated by physicians. APCs who participated in the study were required to have been practicing for at least 12 months and have three or more months’ experience in providing medication abortions. To prove competency, APCs needed to complete at least 40 procedures. The study conclusively showed that complication rates as a result of the procedure were equivalent for both physicians and APCs. This critical research provided the key findings that supported legislative change and could be used by other states in efforts to expand abortion care.

Once the study was completed, legislation was drafted and introduced in the California State Assembly. It did not pass out of committee on the first attempt, but after advocates gained the support of multiple professional associations, reproductive justice and health organizations, and community and legal groups, the bill, A.B. 154, passed, and the governor signed it into law in 2013. The legislation removes the physician-only restriction for first-trimester aspiration abortions and allows APCs to perform this procedure if they complete the competency-based training used in the UCSF study and have a current license to practice.

In addition to increasing the number of clinicians providing aspiration abortions, this legislation paves the way for abortion to be reintegrated into primary care clinics and community health centers in California, therefore increasing the number of locations where women can access abortion care. These positive results could also be seen in additional states that pass similar legislation and where unnecessary funding and building-code restrictions have not been passed. At many clinics in states where only physicians perform aspiration abortions, abortions are usually only provided on certain days of the week based on physician availability. Abortion protestors and those visiting the clinic are typically very familiar with the clinic schedule. In California, by eliminating physician-only restrictions that limited when aspiration abortions could be provided, this legislation also reduced stigma for women attending these clinics.

The current state landscape

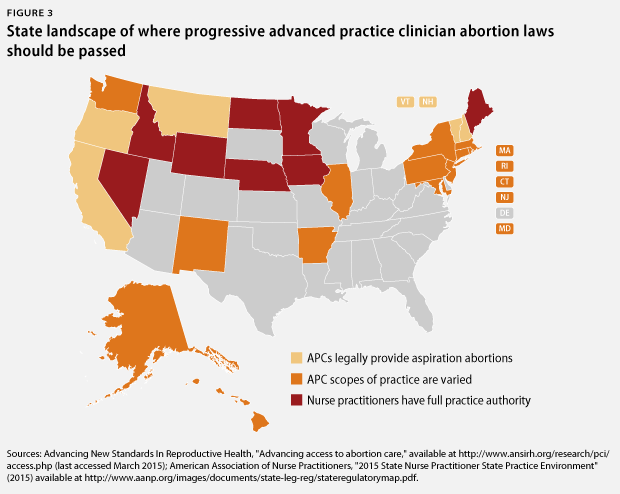

Currently, other than California, APCs only provide aspiration abortions in four states: Oregon, Montana, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Taking into consideration their legislatures, gubernatorial composition, and, in some cases, the regulatory environment regarding medication abortion, several states could potentially pass legislation expanding scopes of practice, thus allowing APCs to provide aspiration abortions in the first trimester. These states include:

- Alaska

- Hawaii

- Washington state

- New Mexico

- Illinois

- New York

- Massachusetts

- Connecticut

- New Jersey

- Maryland

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

Additionally, there are eight states that have full practice authority for NPs but currently have laws that only allow physicians to provide medication abortions and aspiration abortions. These states, where legislation or administrative policy changes could increase the number of abortion providers, include:

- Nevada

- Idaho

- Wyoming

- North Dakota

- Nebraska

- Minnesota

- Iowa

- Maine

States that are not listed above are unlikely candidates to pass this type of legislation in the near future based on their limited scopes of practice for APCs, the composition of their state legislatures and governor’s offices, and/or the regulatory environment for medication abortion.

More than 14 million women of reproductive age live in states where APCs possess varied scopes of practice, government bodies might be more amenable to legislation that would expand abortion care privileges for APCs, and nearly 50,000 NPs and CNMs are licensed to practice. In the states where advanced-practice nurses have full practice authority, there are more than 8,000 NPs and CNMs and 3.3 million women of reproductive age. Abortion rates vary widely between states and not every APC will sign up to receive additional training to provide aspiration abortions, but it is clear that millions of women seeking abortions in these states would be positively affected by laws that allow APCs to provide aspiration abortions.

Conclusion

Abortion remains a very common medical procedure in the United States, yet women experience delays in accessing abortions due to reductions in the number of providers and clinics offering abortion care. In addition, abortion has become an isolated service and is often not included in general women’s health care, leading to further stigmatization of the procedure and of the women who obtain abortions. One way to combat limited access and to reduce stigma is expanding access to abortion care by allowing more clinicians to provide this procedure. State legislatures should pass laws similar to California’s A.B. 154 in order to reduce waiting periods and improve access to abortion care.

Donna Barry is the Director of the Women’s Health and Rights Program at American Progress. Julia Rugg is an Intern with the Women’s Health and Rights Program at the Center.