For many Americans, tax time is also savings time—whether a family is working with an accountant to maximize deductions or debating how to use a tax refund.

This should not come as a surprise. The tax code encourages people to save through billions of dollars in tax incentives for homeownership, retirement, and other goals, including the Saver’s Credit, which rewards low- and moderate-income families who make contributions to retirement accounts. Yet the vast majority of benefits from retirement-tax incentives—about 80 percent—go to the top 20 percent of income earners. Some have suggested, however, that savings incentives help low- and moderate-income families increase how much they save—which generates net new savings—while higher-income earners are more likely to simply move existing savings into tax-advantaged accounts.

More can be done to help working families build wealth so that they can better deal with emergencies. In 2009 about 27 percent of all American households—more than 80 million Americans—were considered “asset poor” according to the Corporation for Enterprise Development. Asset poverty means that these households lack sufficient resources to get by at the poverty line for three months in case of job loss or other loss of income. Excluding houses, cars, and other types of assets that are not typically liquidated in a crisis, however, this number increases to 43 percent of all households. This is nearly three times the national poverty rate of 15 percent.

Similarly, roughly half of all Americans—at all income levels—would “probably not” or “certainly not” be able to come up with $2,000 in 30 days to deal with an emergency, according to a recent nationwide survey by the market research firm TNS Global. This was true not only for about three-quarters of those with incomes of less than $20,000 per year, but also for about 20 percent of respondents earning more than $100,000 annually.

In short, many Americans who may not technically be considered “in poverty” still run the risk of financial ruin. Having even small amounts of savings, however, can help families weather their crises. Without savings, families may seek out predatory loans and fall deeper into debt, or they may become more dependent on government assistance. Savings are also key to planning for the future, whether buying a house or a car, preparing for college expenses, or thinking about a secure retirement.

Tax refunds can help provide a savings opportunity—a “savable moment”—where refund money can be set aside to meet future financial needs. More than 110 million tax filers—77 percent of all American households who file taxes—received a federal income-tax refund in 2010. This includes 76 million tax filers who earned less than $50,000 a year—an average refund of more than $2,300 per filer in this income group. Many tax filers overwithhold during the year—in other words, they have more money taken out of their paychecks than is actually necessary to meet their tax liability. Some economists suggest that this is because taxpayers have not properly filled out their tax forms at work or do not adjust them as circumstances change. But taxpayers may also be attracted to receiving a refund instead of having to worry about paying their taxes in April.

For about 27 million low- and moderate-income tax filers—mostly families with children—this tax refund moment is made more attractive by policies such as the earned income tax credit, or EITC. The credit, which was first enacted in 1975 and expanded in the 1990s, provides families with modest incomes—less than $36,000 to $50,000 per year, depending on family size—with a credit ranging from $3,000 to more than $5,000. Most importantly, the earned income tax credit is refundable: If the credit is greater than the tax filer’s federal income-tax liability—the filer’s obligation to the Internal Revenue Service—the IRS refunds the difference. Since low-income tax filers may not have an income-tax liability, this can provide a sizable financial boost to these families.

Behaviorally, “mental accounting” suggests that larger, less common payments like bonuses and tax refunds are treated differently from regular, small amounts like paychecks. Tax refunds for EITC filers are a prime case. In one study of EITC recipients in two cities, 84 percent used part of the tax refund to pay off debt or cover bills. Sixty-one percent used a portion of their refunds on child-related expenses, and one-third used at least part of their refunds to purchase or repair a car. But nearly half—47 percent—also put aside part of their refund for goals such as a security deposit on an apartment, a down payment on a home, or to cover emergencies. The tax refund moment is an opportunity to put aside hundreds of dollars that may have been more difficult to save during the year.

But to make the most of tax time, savings is only half the battle. Fees for tax preparation and expensive financial products such as refund-anticipation checks—temporary holding accounts for tax-refund dollars—can take hundreds of dollars out of a working family’s tax refund. The National Consumer Law Center reported that in 2008 more than $1.5 billion in EITC payments went toward tax-preparation and refund-anticipation fees. What’s more, some tax refunds are loaded onto prepaid cards that may charge fees just to access refund dollars.

At the same time, some progress has already been made to make tax time a better wealth-building opportunity for working families. In recent years the Internal Revenue Service has made it possible for consumers to automatically split tax refunds into multiple bank accounts, and it has gone after some of the most nefarious and costly tax-refund loans. Pilot programs across the country have also demonstrated that matching incentives and creative messaging can help increase savings rates.

Congress should build upon these initiatives to help working families save at tax time. First, tax reform should create a stronger savings incentive—a refundable, matching Saver’s Credit—and make it available to more low- and moderate-income families. Congress should also make sure that savings opportunities—such as savings bonds and safe, affordable accounts—are available to all tax filers, and it should support free and low-cost tax-preparation opportunities such as Volunteer Income Tax Assistance sites, which saved families receiving the earned income tax credit an estimated $90 million in tax-preparation fees in 2011.

Other government actors should also take action. The Internal Revenue Service and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should continue to monitor financial products targeted to consumers with tax refunds, such as refund-anticipation checks and prepaid cards. And state lawmakers should consider whether asset tests, which force agencies to comb through all financial aspects of potential public beneficiaries’ lives—from bank accounts to the values of used cars to life insurance policies to, in some cases, prepaid burial plots—are discouraging families from saving because saving would threaten their access to public assistance. Encouraging savings could actually reduce dependency.

This issue brief looks at some of the problems low-income families face in building wealth at tax time, the pilot programs and policy developments that have been able to potentially increase savings, and current proposals to make tax-time savings more popular and effective.

Problems

The Saver’s Credit has limited reach

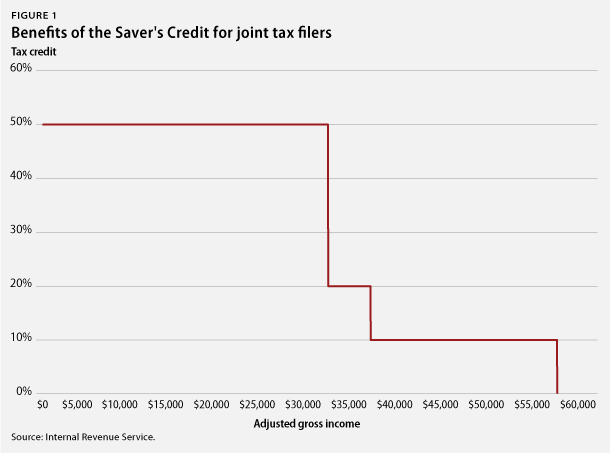

To encourage savings by low-income families, Congress passed the Saver’s Credit in 2001, which rewards saving in employer-sponsored retirement plans like 401(k)s as well as Individual Retirement Accounts, or IRAs. For single filers earning less than $28,750 and joint filers earning less than $57,500 in 2012, the Saver’s Credit is a tax credit of up to 50 percent of the amount saved, with a maximum of up to $2,000 in savings.

In 2010 more than 91 million tax filers reported annual incomes of less than $50,000. Only 6.1 million tax filers claimed the Saver’s Credit—a small fraction of all low- and moderate-income tax filers. One of the main obstacles to broader reach is that the credit is nonrefundable. Unlike the earned income tax credit, the Saver’s Credit cannot exceed the tax filer’s federal tax obligation. As a result, tax filers who pay little or no federal income tax—such as many low-income workers—are generally not able to benefit from it. The credit also only applies to contributions for certain types of retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s and IRAs. Low-income savers may not be familiar with or have access to these accounts. And as income increases, the credit drops off very quickly: It starts at 50 percent for the lowest-income filers, before phasing down to 20 percent for joint filers earning more than $34,500 and 10 percent for joint filers earning more than $37,500. (see Figure 1)

The Office of Management and Budget estimates that the Saver’s Credit cost the government slightly more than $1 billion in foregone revenue in 2011. This is a tiny fraction of an estimated $142 billion in retirement-tax expenditures—dollars that would otherwise be taxed but are not because of credits in the tax code. The vast majority of retirement-tax expenditures help higher-income earners, who also benefit more from tax-advantaged saving because higher tax brackets reduce tax liability more for each dollar saved.

Potential savers have a “leaky bucket,” and may have disincentives to save

Having a tax refund is one thing, but committing it toward saving is another. This is known as the “leaky bucket” problem: With a large refund, it may be tempting to spend the money rather than put a portion of it aside. Knowing that a windfall is coming, tax filers may have already decided to use their tax refunds for a specific purpose, such as paying off debt or taking care of pressing household needs. Looking at planned and actual uses of low-income families’ tax refunds, researchers found that 69 percent of tax filers intended to save a portion of their refunds when they filed their taxes, but only 47 percent actually reported doing so six months later. Pressing financial needs may threaten a savings goal.

Moreover, many states create a disincentive to save by disqualifying people from welfare benefits or food assistance if they exceed certain “asset limits.” If a tax refund is saved rather than spent, in some cases it may trigger these limits, which restrict how much public-benefit recipients can have in their bank accounts as well as other types of holdings, including vehicles, property, and even burial plots. This means that while spending a tax refund has no penalty, potentially saving part of it in a bank account for future needs can threaten access to benefits. Policies vary widely across states and programs, but even when these limits do not apply—or are very high—the belief that families are punished for having savings can discourage public-benefit recipients from putting tax refunds into a bank account.

Even maximized refunds can be eroded by fees

The National Consumer Law Center estimated that of the $49 billion in earned income tax credits in 2008, more than $1.5 billion went toward refund-anticipation and tax-preparation fees. In other words, 3 percent of EITC dollars—government funds designed to help cash-strapped families make ends meet—went directly into tax preparers’ pockets, not to the recipients. Nearly $1 billion went to tax-preparation fees alone. Refund-anticipation loans and refund-anticipation checks may give consumers access to their expected tax-refund dollars faster than they would otherwise be available, but at a high cost. In 2008 the typical refund-anticipation loan cost about $65—in addition to tax-preparation fees—to receive cash one to two weeks before the refund would arrive from the Internal Revenue Service. Some, however, could cost more than $100. For tax filers without bank accounts, a refund-anticipation check offers a temporary account for receiving tax refunds that is faster than waiting for a paper check, and automatically deducts tax-preparation fees, at the cost of $30 or more. But for tax filers with bank accounts, refund-anticipation checks deliver refunds no faster than they would otherwise be directly deposited.

In 2010 the average tax refund for filers earning between $10,000 and $50,000 was more than $2,500. Overall, $300 or more of the tax refund could go to these fees—while low-income filers using free options such as Volunteer Income Tax Assistance sites or Free File software could receive their refunds in one to two weeks by direct deposit. Yet roughly 20 million tax filers in 2008 used a refund-anticipation loan or refund-anticipation check, including roughly half of all filers claiming the earned income tax credit. In fact, a 2008 Government Accountability Office report found that the refund-anticipation loan market was so lucrative that in some cases, car dealers and shoe stores would offer tax-preparation services in order to make the loans and encourage the tax filers to use their loan proceeds to buy goods.

Refund-anticipation checks still exist today, but recent actions by banking regulators and the Internal Revenue Service have greatly cracked down on banks offering refund-anticipation loans. But some nonbank actors, such as check cashers and payday lenders, are starting to offer these services. And some tax preparers have found another opportunity to gain revenue from low-income families’ tax refunds—high-cost prepaid cards. Prepaid cards can be a valuable alternative to bank accounts, since they generally cannot be overspent and are an effective substitute for cash. While innovative, some card offers may be far better than others that have high initial opening or monthly maintenance fees.

Progress

The Internal Revenue Service has taken steps to make savings easier

In 2007 the Internal Revenue Service made available a new tool to facilitate savings through Form 8888, which enables a tax refund to be split into multiple accounts. This change addresses the “leaky bucket” issue, in which a taxpayer might intend to save part of a tax refund but end up spending the entire refund instead. A tax filer receiving a $1,000 refund, for example, can have $500 automatically deposited in a checking account and the other $500 deposited in a savings account. Prior to this change, the same taxpayer would have to choose one account or the other in which to deposit the entire amount.

Since 2010 Form 8888 has allowed tax filers to use part of their refund to buy U.S. savings bonds in $50 denominations as well. This is not the first time the IRS has promoted savings bonds: From 1962 to 1968 tax refunds were available either as a check or as a savings bond. As of January 2012 this is the only remaining way to buy paper savings bonds; the U.S. Treasury now almost exclusively sells them electronically. Yet savings bonds remain attractive to some consumers who may not have a bank account or home Internet access, leading to controversy over the move away from paper bonds.

The IRS has also helped rein in high-cost refund-anticipation loans. Tax preparers making these loans face some risk that a portion of the tax refund will be garnished to pay for outstanding federal debts. In the early 1990s and again from 1999 onward, the IRS provided a “debt indicator” that helped tax preparers identify if refunds were likely to be recaptured. Starting in the late 2000s, banking regulators informed sponsoring banks that the loans were too risky, and in 2011 an IRS administrative change eliminating this indicator made it difficult for tax preparers to determine the risk of these loans. As a result, refund-anticipation loans have largely disappeared from mainstream banking actors, although some nonbanks continue to make these loans.

Public and private actors have demonstrated new ways to boost savings

Several pilot programs around the country have looked at the role of matching funds as a behavioral “nudge” and more popular alternative to tax credits. Matching funds are more concrete than credits—and demonstrations have shown that they may help boost savings by low- and moderate-income families at tax time.

In 2005 14,000 low-income tax filers at H&R Block offices in the St. Louis metropolitan area were randomly offered a matching contribution if they opened an Express IRA—the retirement savings account that H&R Block marketed at the time. Of those who were offered no match at all, 3 percent still decided to open an account and save. Of those who were offered a 20 percent match, 8 percent opened an account, and of those who were offered a 50 percent match, 14 percent opened an account. In other words, the match made tax filers between two and five times as likely to save. Amounts saved also increased dramatically in the presence of a match, with savers offered a match contributing four to eight times as much as those not offered a match.

In 2008 New York City launched SaveNYC, a pilot program in collaboration with select free Volunteer Income Tax Assistance sites, which matched 50 cents of every dollar saved, up to a maximum of $500 in matching funds—provided that the savings was not touched for one year. Roughly 9 percent of eligible tax filers participated from 2008 to 2010, even though matching dollars were limited. Over this three-year period, more than 2,200 people chose to open savings accounts through SaveNYC, collectively saving more than $1.7 million. Eighty-one percent kept their savings for the full year, yielding a total of $2.3 million in savings, including matching funds. In 2010, with support from the U.S. Social Innovation Fund, the pilot program was expanded to Newark, New Jersey; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and San Antonio, Texas, under the name SaveUSA. The evaluation is still underway, but during its first year, 73 percent of participants across the four cities were able to open a savings account and keep their savings untouched.

A new savings pilot program called Refund2Savings also looks at the role of messaging and behavioral defaults. Researchers at Duke University and Washington University in St. Louis teamed up with tax preparer Intuit to test the potential for marketing savings through split refunds. Launched in 2012, the Refund2Savings demonstration reached more than 80,000 low-income tax filers who used Intuit’s TurboTax Free File software.

After completing their tax returns, filers saw a motivational prompt, such as “Would you like to save for a rainy day?” After the prompt, they may also have viewed a suggested tax refund divided up into checking and savings amounts, such as 75 percent in checking and 25 percent in savings, or vice versa. Those behind the pilot program hope to reveal how likely tax filers are to save based on different default amounts and savings messages. While official findings have not yet been released, providing a default savings suggestion has shown greater savings than the study’s control group, in which no motivational prompt or savings suggestion was given. In its 2013 pilot, Refund2Savings will also be offering savings bonds as an alternative to accounts.

Tax preparers have an interest in these types of activities because they ultimately add value for clients who have a number of tax filing options. Intuit has expressed interest in the Refund2Savings pilot program because it is “a unique opportunity to build savings while filing a tax return, making saving easier and, in turn, generating customer satisfaction and loyalty.” Helping working families save at tax time can be attractive to both the preparer and the client.

Common-sense Saver’s Credit reforms have been proposed

Recognizing the limitations of the Saver’s Credit, President Barack Obama’s 2011 budget included a proposal to expand the credit to more low- and moderate-income families. The proposal would increase eligibility to joint filers earning as much as $85,000, and would convert the current nonrefundable credit into a refundable credit.

Along similar lines, the Aspen Institute’s Initiative on Financial Security recently proposed the Freedom Savings Credit. The Freedom Credit would also extend the Saver’s Credit to joint filers earning up to $85,000, make it refundable, and eliminate the “cliffs” in the existing credit so that a much larger share of tax filers would be able to receive the maximum amount of savings. Most importantly, the newly refundable credit would be automatically deposited into the tax filer’s retirement account—effectively turning the credit into a matching fund. This credit would build opportunity for sizable retirement savings; matching the savings of an individual putting aside $13 per week, over 30 years the portfolio could grow to as much as $150,000 based on a target-date investment strategy. The annual cost to the government of the Freedom Savings Credit is approximately $3 billion.

The New America Foundation has taken a somewhat more ambitious approach. Its Financial Security Credit proposal would provide a dollar-for-dollar government match on savings up to $500 for low- and moderate-income tax filers. Most notably, the match would be available to savings vehicles other than retirement accounts. The match would include tax-advantaged education savings accounts such as Section 529 higher-education plans and Coverdell accounts, as well as U.S. savings bonds and certificates of deposit, or CDs. Savers would also be able to open an account directly on the tax form if they do not already have one.

Under the Financial Security Credit proposal, the match would be available to tax filers earning up to 120 percent of the earned income tax credit’s eligibility level—for example, approximately $44,000 in 2012 for a single parent with one child, or $56,000 for a married couple with two children. By rewarding a wide range of savings behaviors, the proposal would facilitate savings for different life goals at an estimated cost to the government of $4 billion per year.

Members of Congress have been receptive to the idea of Saver’s Credit reform. In 2008 Sen. Robert Menendez (D-NJ) introduced the Saver’s Bonus Act (S. 3372), which largely follows the Financial Security Credit proposal. And in 2012 Rep. Richard Neal (D-MA) proposed a version of the Freedom Savings Credit, entitled the Savings for American Families’ Future Act (H.R. 6472). Unfortunately, neither of these bills made it out of committee.

All of these proposals have a modest cost in the overall government framework of more than $140 billion in annual tax expenditures for retirement savings. They address the existing Saver’s Credit’s limitations and build on research that shows how to generate new savings—not just transitions from one type of account to another.

Recommendations

Pilot programs by local governments and tax preparers have made it easier for some working families to save at tax time through matching incentives and behavioral nudges. The Internal Revenue Service has also played an important role by enabling automatic refund splitting and greatly reducing the presence of costly refund-anticipation loans. But making tax-time savings work effectively for more low- and moderate-income families will require additional action by Congress and the executive branch.

1. As part of tax reform, Congress should convert the Saver’s Credit into a refundable credit that is deposited directly to the tax filer’s account

As a refundable credit, the Saver’s Credit would reach low-income workers who would otherwise be unable to claim the credit because they may not have a tax liability. And depositing the credit into the tax filer’s account reduces the possibility of leakage and effectively matches the tax filer’s savings. This not only encourages working families to save—whether at tax time or throughout the year—but it also allows savings contributions to increase more quickly.

A proposal to make the Saver’s Credit refundable was included in President Obama’s fiscal year 2011 budget. The president’s budget proposal also recommended extending the credit to joint tax filers who earn up to $85,000 per year and eliminating cliffs in the credit as it currently stands so that more tax filers would be able to receive the maximum match. These changes would cost the government approximately $3 billion per year out of the more than $140 billion in tax expenditures for retirement—a modest investment.

Policymakers should also consider what types of accounts should be eligible for the Saver’s Credit. Some have proposed expanding eligibility for the credit to include not only retirement accounts but also education savings in Section 529 higher-education plans, Coverdell accounts, savings bonds and CDs. They argue that retirement is not an attractive savings goal for low-income families and that savings for other life goals may be more appealing. But regardless of whether a converted Saver’s Credit can be used only for retirement accounts or for broader savings opportunities, reforming the credit will make savings more attractive to millions of low- and moderate-income families.

2. Consumers should have access to a savings vehicle at tax time even if they do not already have a savings account

Consumers expecting a tax refund should have the ability to automatically save a portion of their refund before they have an opportunity to spend it. Tax filers who already have checking and savings accounts can automatically split their refunds. And some tax preparers, such as Volunteer Income Tax Assistance sites, may have banks or credit unions on hand to open new savings accounts for filers who may not have them. But not all tax filers currently have the ability to open an account.

The Internal Revenue Service has enabled tax filers to purchase U.S. savings bonds at tax time, and it should continue to do so. Savings bonds are attractive to consumers who may not have or want other savings vehicles. But other types of accounts should be made available to consumers at tax time as well. One possible approach, as advocated by the New America Foundation as part of their Financial Security Credit proposal, would be for the Treasury Department to allow banks to competitively bid for the opportunity to offer savings accounts for tax refunds. All savings and investment vehicles that may receive federal tax refunds must be safe and affordable for consumers.

3. Congress should support free and low-cost tax preparation services, such as Volunteer Income Tax Assistance sites

The president’s budget for fiscal year 2013 recommended appropriating $12 million to matching grants for these nonprofit tax preparation sites, which prepare millions of tax returns for filers with an average adjusted gross income of $21,000. Given that low-income tax filers may lose several hundred dollars of their refunds to tax-preparation fees, these volunteer-staffed sites help consumers keep their maximum refund—dollars that can then be either saved or spent.

Other opportunities can also reduce the costs of tax preparation. An improved online free-file program could also help broaden outreach to working families. As demonstrated by the Refund2Savings pilot, this may present a low-cost savings opportunity. Paid preparers, too, may wish to seek out lower-cost opportunities. All tax preparers have an important role to play in building financial stability at tax time, but a balance must be struck between reasonable tax-preparation costs and fees and practices that ultimately erode the value of the tax refund.

4. The IRS and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should continue to monitor tax-refund financial products such as refund-anticipation checks and prepaid cards

While high-cost refund-anticipation loans have largely disappeared from the landscape as a result of IRS actions and the activity of banking regulators, refund-anticipation checks remain a very expensive way to receive a refund. Moreover, prepaid cards that receive government payments must already meet many stringent requirements, but some cards may still have high fees depending on how the card is used. Again, dollars that are not directed toward fees can be better spent on necessities or saved for a rainy day.

5. Federal and state lawmakers should ensure that asset limits in state programs do not threaten small amounts of savings

In some states, holding as little as $1,000 in savings can disqualify someone from receiving public benefits. While this may seem like an attempt to steer benefits toward the truly needy, it also discourages those receiving public assistance from attempting to save and move out of poverty. State human-services agencies must remain aware of the power of asset limits to discourage savings. Even after policies change, perceptions may remain, as public assistance recipients continue to believe that their benefits are threatened if they attempt to save money.

Conclusion

Tax time presents an opportunity for low- and moderate-income families to put a portion of their tax refunds toward emergencies and save it for future goals. While the current Saver’s Credit seeks to reward savings, its limitations mean that many of the families intended to benefit from the credit ultimately do not. But innovations by the Internal Revenue Service, like Form 8888, have made it easier for families to save, and cracking down on refund-anticipation loans has helped millions of families keep more of their tax refunds.

When Congress considers tax reform, it should look to facilitate tax expenditures that can ultimately change behavior, such as matched savings for working families. Stronger supports for tax-time savings can make American households more financially capable to deal with emergencies and plan for the future.

Joe Valenti is the Director of Asset Building at the Center for American Progress.