President Donald Trump recently said that the U.S. economy is “stronger than ever before” and points to his tax plan as one of the major reasons why.1 But the fact is that workers are not getting ahead in the Trump economy. Official data released in recent weeks have shown that workers’ wages are flat or even slightly down, in real terms, over the last year.2 These data fly in the face of many tax plan boosters who have claimed that the bill’s passage has already been a boon to middle-class workers.

This Friday, the U.S. Department of Commerce will release its first estimate of the nation’s economic output in the second quarter of 2018. For a number of reasons, second-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to be relatively strong. But one quarter’s GDP estimates hardly indicate that the economy is experiencing the sustained, broad-based growth that tax cut proponents promised would happen. Indeed, as the wage data show, the economy’s gains have not trickled down to regular workers. In fact, President Trump’s policies have only made it harder for them to get ahead.

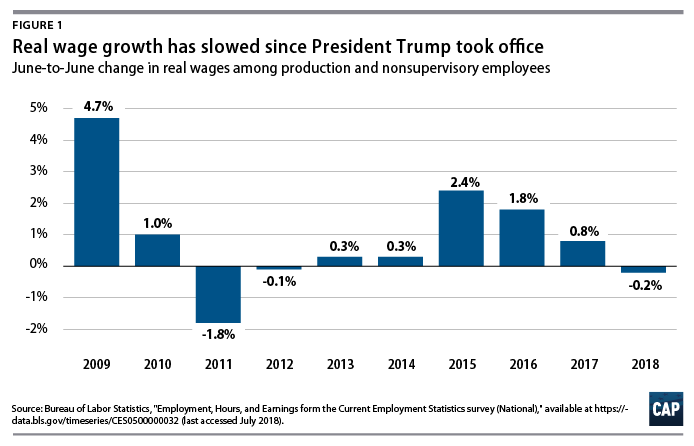

Workers’ real wages have been entirely flat over the last year

GDP growth is the biggest-picture view of the economy; it’s important for macroeconomists who focus on long-term shifts in what the U.S. economy produces. GDP, however, is only one measure of economic progress, so its effectiveness at measuring workers’ well-being is limited. In the modern economy, benefits are shared unequally. As economic benefits have gone increasingly to those at the top, overall economic growth tells us less than it once did about how the living standards of all Americans are changing. To be sure, economic growth is an important goal, but it’s naïve to ignore the growing disconnect between changes in economic output and living standards for the vast majority of workers—especially when there are much more applicable measures of how workers are faring.

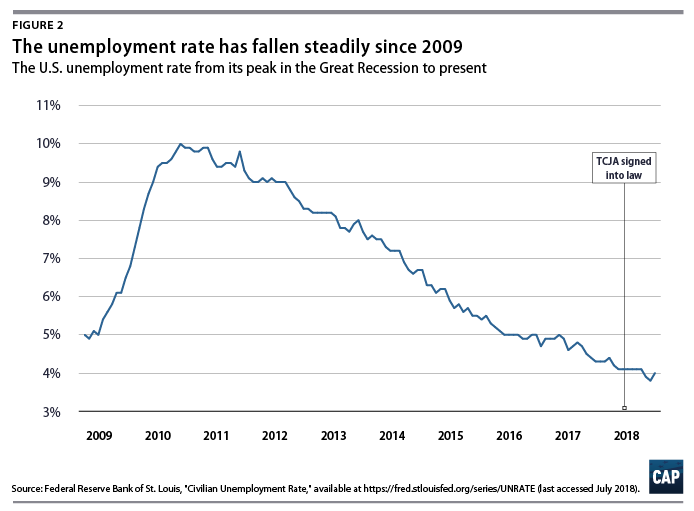

Outside of the very wealthy, virtually all working Americans’ income and standard of living is determined by wages. Unfortunately, wage growth has been at best mediocre for most of the last four decades. Since the Great Recession, nominal wage growth has been worryingly low, exceeding 2.5 percent only a handful of times through the end of 2017—growing barely faster than inflation.3 But with the unemployment rate continuing to fall, many experts predicted workers were poised to finally see gains outpace inflation this year.4

That hasn’t happened. In fact, when adjusting for inflation, wages have actually fallen this year. It’s not that wages haven’t ticked up at all—they have, in part due to increases in the minimum wage.5 But even with slightly faster nominal wage growth, workers have lost ground because inflation has picked up more than wage growth.

Essentially, the administration was in a position to do nothing and take credit for the continuing improvement of the economy—but that’s not what happened. A large tax cut for corporations and the wealthy put upward pressure on interest rates, making large purchases more expensive. Changes in the U.S. posture toward the Middle East have contributed to significantly higher gas prices, while the early effects of the administration’s trade shenanigans have started to drive up the price of imports.6 Each of these issues by itself is not huge, but the sum total is enough that for the second month in a row, real wages are lower today than they were a year ago.7

Specifically:

- Real average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls were exactly the same in June as they were a year ago, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).8

- Real average hourly earnings for rank-and-file employees—the roughly 80 percent of workers who are categorized as “production and nonsupervisory employees” by BLS—decreased slightly, by 0.2 percent, from last June to this June.9

- Real median weekly earnings have also decreased slightly.10 While nominal weekly median earnings rose 2 percent from the second quarter of 2017 to the second quarter of 2018, they were more than offset by inflation, which was 2.7 percent over that period.11

With reports pointing to idiosyncratic factors playing a potentially large role in the second-quarter GDP—this brief will discuss soybean exports later—it’s worth taking this figure with an extra grain of salt. It’s also worth noting that while we’re waiting for GDP data, wage data already exists—and it’s moving in the wrong direction. For regular working families, real wages are what matter.

Despite promises and PR stunts, the corporate tax cut has not boosted wages

Stagnant wages are not what the proponents of the tax cut said would happen. They predicted that corporate tax cuts would ultimately translate to higher wages for U.S. workers. The White House estimated that the corporate tax cuts would boost the average family’s wage and salary income by $4,000 after a few years.12 That’s $4,000 after adjusting for inflation, over and above any increases they would have seen over time in the absence of the tax bill. But so far, real wages are flat or slightly down since the tax bill passed.

The White House’s $4,000 promise to American families was outlandish, drawing from cherry-picked studies about the effect of corporate tax cuts on investment. It ignored other evidence, as well as features of the tax bill that disincentivize investment in the United States—including the shift to a permanently lower tax rate on foreign profits and specific provisions that reward locating investments outside of the United States.13

Most importantly, the White House’s claim was based on an increasingly tenuous connection between what workers produce, or productivity growth, and what they are paid for their work—wage growth.14 In other words, the White House based its promise on the theory that corporate tax cuts would lead to a boom of new investment, that this would make businesses much more productive, and that workers would succeed in bargaining for the gains from that increased productivity. Unfortunately, recent experience has shown that even when productivity increases, workers do not necessarily share in the gains; in fact, they have barely benefited from productivity increases in recent decades.15

But tax cut proponents have not only stuck to outlandish promises about future wage growth—they have also claimed that workers are already big winners from the tax law. White House economist Kevin Hassett has recently claimed that “wages have gone up faster than we thought” and implied that the $4,000 promise has already been fulfilled for many American families.16 The actual data on real wages belie those claims.

The wage data also expose the much-hyped corporate bonus announcements that came on the heels of the tax law’s enactment as a misleading public relations exercise. Soon after President Trump signed the tax bill into law last December, some of the large companies that lobbied for and received tax cuts issued press releases highlighting year-end bonuses and other worker benefits supposedly resulting from the tax law.17 But these press releases conveyed a highly misleading picture of the tax law’s actual impact: They pertained to only a small share, less than 5 percent, of American workers.18 And there was no reason to accept at face value the claim that the bonuses were prompted by the tax bill—in 2017, nearly 40 percent of workers received some kind of bonus.19 What’s more, the vast majority of the announcements pertained to one-time bonuses that often substitute for lasting pay raises.20 Some of the firms that announced bonuses to much fanfare actually laid off employees.21

Trump policies make it even harder for workers to secure higher wages

The sorry state of wage growth in the U.S. economy should not be news to anyone by now. But as the longest economic expansion in modern history continues through the Trump administration, economists are growing increasingly concerned about an economy that routinely delivers healthy profits to big business without raising wages for workers.22 It’s not surprising that a comprehensive, decadeslong anti-worker agenda could stack the deck in favor of corporations. And this year’s wage data have made it crystal-clear that that’s exactly what has happened. If workers can’t get a raise with an economy near full employment and 93 months of uninterrupted job growth, it’s not clear if they ever will.

Yet, in spite of campaigning as a populist who was angry about the state of American workers, President Trump has doubled down on the formula that brought this about—relentlessly chipping away at worker’s rights. Worker protections introduced under the previous administration, whether to protect workers from unscrupulous financial advice and from pay practices that cost workers billions by the administration’s own analysis, or to ensure overtime work earns overtime pay, have faced challenges.23 With worker power heavily diminished, the administration has used the courts to tip the scales even further—most prominently by appointing the deciding vote in a case designed to weaken public sector unions.24

A lack of worker power is corrosive and makes U.S. workplaces less safe and the economy less productive. Discrimination remains a barrier to a fair paycheck for virtually all Americans at some point in their lives; too many Americans face this disadvantage every day.25 In an economy where corporations assume they will get away with discriminating against pregnant or older workers, and where companies have used contracts to ban low-wage workers from seeking other opportunities, the asymmetric power in today’s workplace is an increasing burden on the economy.26

These outcomes are not the result of the invisible hand, but of a market that has been set up to favor the wealthy. There are concrete steps policymakers can take to reverse this trend, but 1 1/2 years in, this administration has consistently taken sides against workers. Until the government stops tipping the balance of power toward corporations, GDP growth is increasingly becoming just a number for most workers.

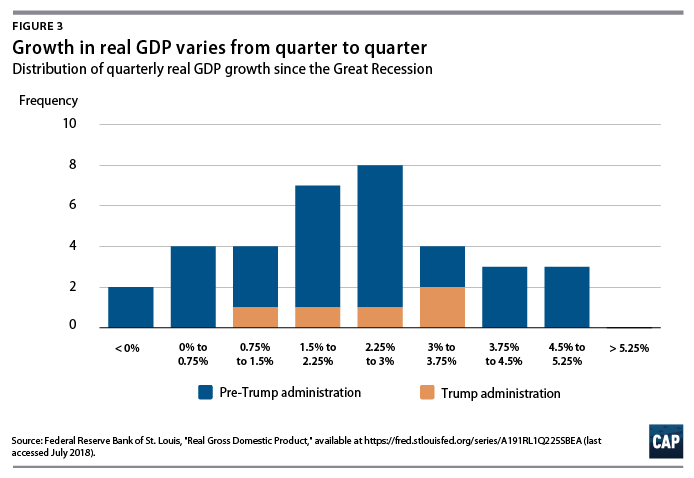

Context around second-quarter GDP tells a consistent story, regardless of how one number comes out

It is critical to put one quarter’s GDP estimate in context. While mainstream public and private forecasters project that the U.S. economy will grow about 2 percent per year over a long-term horizon, the Trump administration claimed that its policies would boost economic growth to 3 percent over the long-term. During the 2016 campaign, Trump even promised sustained 4 percent growth or higher.27 If GDP growth reaches those levels for one quarter, it by no means indicates that growth will continue at that level in perpetuity.28 In fact, since 2009, GDP grew faster than 3 percent during 10 quarters, including four quarters of growth above 4 percent. In the third quarter of 2014, it grew at 5.2 percent.29 None of these strong quarters portended a permanently higher growth path.

In fact, this quarter’s GDP will probably be boosted by a number of factors that likely will not be sustained—especially not under the policies proposed by President Trump and other conservatives. GDP growth in 2018 will be boosted by the bipartisan agreement to increase government spending, as purchases by the government add directly to GDP—but both President Trump and House Republican budgets propose to reduce spending. The tax bill is providing a near-term boost in demand. But in an economy where the Federal Reserve is raising rates, the demand boost is likely to be dampened—and will ultimately wear off. And, of course, the bill was financed with nearly $2 trillion of higher deficits, which will create pressure on government services and investments over the long term.30 This quarter’s GDP growth numbers may also be inflated by a sharp surge in soybean exports, caused by buyers of U.S. soybeans apparently stocking up in anticipation of escalating trade tariffs. One economist has estimated that the “soybean surge” will add 0.6 percent to the GDP growth rate for the second quarter. But that effect will quickly reverse itself in future measurement periods.31

To date, there is scant evidence that the tax law has produced the boom in business investment that its sponsors predicted. Indicators of new investment—such as private nonresidential fixed investment and manufacturers’ new orders of capital goods—have risen modestly but are still below their levels from only a few years ago.32 Instead of investing their tax cuts, large corporations are simply passing the tax cut windfall to their shareholders in the form of stock buybacks. By buying back their shares, firms pay out cash to shareholders rather than investing it in equipment, their workforce, or research and development. Since the tax law was enacted, firms have announced more than $600 billion of buybacks and cash distributions to shareholders are on pace to reach $1 trillion this year—a record pace.33

As the Trump administration and proponents in Congress predicted, the tax cut is not paying for itself. The Congressional Budget Office projects the tax law to increase deficits by $1.9 trillion over the next decade.34 In fact, this month, the Trump administration revised its projections for the coming fiscal year and now projects the deficit to exceed $1 trillion—double its original projection.35 Tax revenue from corporations has plummeted—not surprising given the massive corporate tax cuts contained in the law.36

Conclusion

GDP is not a measure of Americans’ well-being, let alone that of middle- or working-class families. While GDP measures overall output, it does not reveal who benefits from expanding output. For example, GDP is one-third bigger in real terms than it was in 2000, but real median household income is only barely above where it was at that point.37 The gains have accrued disproportionately to high earners and owners of capital—America’s rich, in other words. The flat real wages that U.S. workers have experienced over the past year signal that workers are not getting a larger share of the economic pie.

Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center for American Progress. Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center.