This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

The employment situation report, released Friday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS, tells the same story we have seen for much of 2014; the recovery has gathered steam, and job growth has accelerated, but not nearly fast enough to produce wage growth for most Americans. In October, the top line unemployment rate edged down slightly, to 5.8 percent, and we added 214,000 jobs. Beneath the top line numbers, we are seeing much more strength in hiring than we have throughout the recovery starting in 2009. However, all those added jobs are still not enough to generate the wage growth that Americans have been missing for years.

Looking at the past few months, we are starting to see hiring and the overall health of the labor market pick up for everyone. The two broadest measures of labor-market health—the employment-to-population ratio and the U6 measure of unemployment, which is the broadest measure of unemployed and underemployed workers—continue to improve significantly. Over the past year, we have seen the employment-to-population ratio rise by a full percentage point, from 58.2 percent a year ago to 59.2 percent in October. Meanwhile, U6 has declined significantly from 13.7 percent a year ago to 11.5 in October, and we have made particularly impressive progress over the past few months. Including October’s 0.3 percentage point decline, the most comprehensive measure of unemployment fell from 12.2 percent in July to 11.5 percent in October.

The employment picture for subgroups such as African Americans and Latinos held steady last month, which is better news than it seems. Subgroup measures are more volatile, and these groups experienced major employment gains in September. The fact that both groups held on to these gains—with Hispanic unemployment declining from 6.9 percent to 6.8 percent—is excellent news considering that the rate was 7.8 percent as recently as July and 9 percent a year ago. African Americans also experienced a modest decline in unemployment rates this month, falling from 11 percent to 10.9 percent, but again the picture is much more promising if we look over a longer time horizon. The unemployment rate for African Americans was 13 percent a year ago, so even though the rate is still far too high, October’s gain represents important progress. The experience of African Americans and Latinos is especially important, as these groups tend to be younger and have more volatile employment statistics, so continued progress here confirms that employment growth is robust.

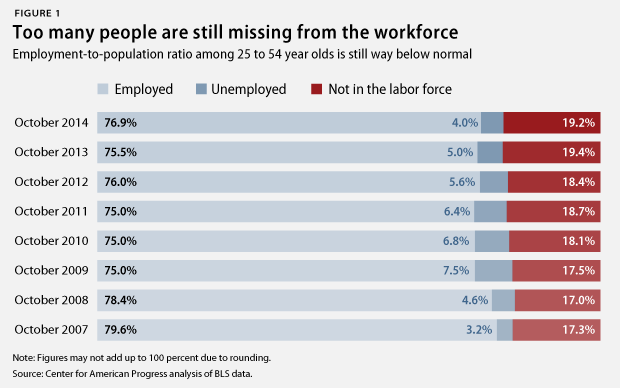

Unfortunately, almost all of the good news in the employment picture comes in the form of gains from the recent past. Even when looking only at prime-working aged Americans, the labor force is still considerably underutilized in historical context. In October 2007, nearly 80 percent of Americans between the ages of 25 and 54 we employed; today, that number is just below 77 percent.

If you’re concerned about inflation, this decline to 77 percent is great news, because this slack in the labor market is restraining wage and compensation growth. If you’re concerned about your paycheck, this isn’t great news, because this slack in the labor market is restraining wage and compensation growth.

Even with 3.8 million jobs added, and 1 million fewer Americans working part time for economic reasons—including another 76,000 in October—there remains little indication of wage pressure. We also saw the share of very short-term unemployed Americans, those off the job for five weeks or less, increase in October, another sign that the labor market is returning to normal levels of health.

The signs of a healthy labor market are everywhere, just not in wages.

The question is how much longer we will need the economy to keep performing this well before we shake off the hangover from the Great Recession and see the employment growth that is finally reaching all Americans translate into wage growth that reaches all Americans.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center for American Progress.