This issue brief contains a correction.

The National Institutes of Health, or NIH, headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, is the agency tasked with leading the federal government’s efforts in biomedical research. As part of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIH is the largest funder of biomedical research in the world. In fiscal year 2013, 92 percent of the agency’s $29.1 billion in budget authority supported research programs and centers, training programs, research and development contracts, and other research awards. The remaining 8 percent covered research management and support and other administrative costs such as buildings and facilities management.

The agency has historically enjoyed a great deal of bipartisan support, and as a result, NIH has seen its funding increase significantly over the past several decades. This support has enabled NIH to form the foundation of America’s biomedical research sector, which leads the world in research spending and innovation. NIH funding has fared well relative to other discretionary programs, even as the federal government began reducing discretionary spending in FY 2011.

These funding figures, however, obscure a critical factor that affects America’s capacity to continue leading the world in biomedical research—inflation. The cost of conducting biomedical research is increasing faster than the cost of other goods and services in the economy. As a result, although much was made of the partial rollback of sequestration in FY 2014 and FY 2015 under the Murray-Ryan budget deal, this partial relief ultimately will do little to stem the trend in recent years of rapidly diminishing purchasing power for biomedical research funding dollars.

Under sequestration in FY 2013, NIH awarded 722 fewer grants than in FY 2012. The steadily declining budget allocations for NIH from FY 2010 through FY 2013 contributed, in part, to the steady decline in grant-application success rates, which decreased each year during this period and fell to an all-time low of 16.8 percent in FY 2013. Aside from the very real impact that this reduction in grants is having on the lives of researchers who are unable to pursue their livelihoods, the impact on society at large will not be felt to a large extent either today or tomorrow, but it will absolutely be felt over the next decade or two. In order to put NIH funding back on track, significant new investments must be made in the coming years to cement the federal government’s commitment to biomedical innovation.

What is NIH?

The National Institutes of Health, which traces its roots back to 1887, has touched every aspect of American health and wellness, while simultaneously facilitating innovation in the private sector. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, life expectancy at birth in the United States increased from 57 years in 1929 to 78 years in 2008. NIH’s work has contributed immensely to the increase in life expectancy and overall wellness in America, partly through research dedicated to preventing and treating illnesses that once contributed significantly to untimely death among children and working-age adults. Data from The New England Journal of Medicine on causes of death in America highlight the stark differences in life and death in America over the past 100-plus years. Whereas in 1900 the top three causes of death in America were influenza, tuberculosis, and gastrointestinal infections, the impact of those illnesses on mortality in 2010 was almost nonexistent. The development of a vaccine in the early 1980s safe enough for infants to combat the flu strain Haemophilus influenzae type b resulted from NIH-funded research.

NIH-funded researchers are close to the creation of a universal flu vaccine—one that would provide protection from multiple flu strains, as opposed to a specified vaccine for each year. As antibiotics proved effective at combating tuberculosis during the mid-20th century, strains of the disease began developing resistance to the drugs. This development has led NIH to support research to develop new drugs to counteract antibiotic-resistant forms of the disease. And while cancer is the second-leading cause of death in America today, death rates from cancer have fallen significantly, due in part to NIH-supported efforts. According to the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, NIH-funded research “has played a role in every major cancer prevention, detection, and treatment advance” over the past several decades.

In pursuit of its mission to “seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability,” the agency’s mission statement states the following four goals:

- “To foster fundamental creative discoveries, innovative research strategies, and their applications as a basis for ultimately protecting and improving health …”

- “To develop, maintain, and renew scientific human and physical resources that will ensure the Nation’s capability to prevent disease …”

- “To expand the knowledge base in medical and associated sciences in order to enhance the Nation’s economic well-being and ensure a continued high return on the public investment in research …”

- “To exemplify and promote the highest level of scientific integrity, public accountability, and social responsibility in the conduct of science.”

What are the economic benefits of NIH funding?

The economic benefits of NIH research and innovation are manifold: NIH research supports and promotes economic activity in the private sector through the development of new techniques and technology, while also preventing the societal loss of economic activity through the treatment and eradication of life-threatening illnesses. A 2001 National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER, study found a “rate of return to public sector research as measured by its effect on the private sector” to be as high as 30 percent. This return on investment is not only attributable to private industry’s ability to utilize and build upon publically financed basic research but also to its utilization of new “technological capabilities, such as genome sequencing machines and high resolution imagers.”

Moreover, the NBER study found that of the 21 drugs with the highest therapeutic impact on society introduced between 1965 and 1992, 14 resulted from key enabling discoveries funded by public research. An economic model co-produced by the University of Chicago and the NBER estimated that the “social value” of increases in longevity and health improvements totaled $95 trillion between 1970 and 2000.

The vast majority of NIH funding supports research conducted in universities and the private sector through the NIH Office of Extramural Research, or OER. In FY 2013, roughly 81 percent of the NIH budget funded extramural research through research grants, research training, and research and development contracts. This funding is awarded through roughly 50,000 competitive grants and supports more than 300,000 researchers in universities and research institutions around the world. OER supports research programs such as Vanderbilt University’s AIDS Clinical Trials Unit and the Accelerating Medicines Partnership, a public-private partnership between the NIH, the Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, private industry, and non-profit organizations to “speed up the search for treatments for some of the world’s most devastating diseases—Alzheimer’s, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.”

The Intramural Research Program, or IRP, comprises all of the in-house research conducted at the 27 institutes and centers that make up NIH and funds a staff of more than 4,000 postdoctoral fellows and 1,200 principal investigators. The basic research discoveries of the IRP have, in turn, led to applied public and private research that has resulted in tangible benefits in the lives of everyday Americans. For example, NIH research efforts that deciphered the human genetic code have “led to greater understanding of genetically based diseases, to better antidepressants, and to drugs specially designed to target proteins involved in particular disease processes.”

In FY 2014, NIH will begin funding the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies, or BRAIN, Initiative, aimed at advancing our understanding of the human brain to develop innovative treatments and drugs to address neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and depression. Additionally, NIH is developing the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements, or ENCODE, project, which to date has enabled NIH researchers to link more than 80 percent of the human genome to specific biological functions, which will ultimately lead to better prevention and treatment of illness.

What are the historical trends in NIH funding?

The history of funding for the National Institutes of Health and recent trends in the agency’s funding obscure a critical component in the financing of biomedical research: The cost of conducting biomedical research, as measured by the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index, or BRDPI, has increased significantly over the past several decades. The BRDPI, which measures inflation in the biomedical research sector, is tracked annually by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The index tracks the changes in prices of the inputs required to conduct biomedical research, including labor, supplies, and equipment. As is the case with inflation generally, in the same way that a dollar does not purchase as many eggs or sticks of butter as it previously would, the purchasing power of biomedical research funding also declines over time. However, the cost of conducting biomedical research has increased much faster than inflation generally. From 1950—the earliest year for which the BRDPI is available—to 2010, the cost of biomedical research increased 14 times over, whereas overall inflation increased roughly seven-and-a-half times over. As a result of inflation in the biomedical research sector, viewing NIH funding simply through the lens of nominal dollars or relative to the overall budget and gross domestic product, or GDP, distorts the true impact of NIH funding dollars.

The past several decades have witnessed a consistently increasing federal commitment to biomedical research, as evidenced by NIH’s steadily increasing budget. From FY 1977 through FY 2010, NIH funding, adjusted for BRDPI inflation, increased by an average annual rate of 2.9 percent. In the eight years between the beginning of President Bill Clinton’s second term in FY 1998 through the end of President George W. Bush’s first term in FY 2005, NIH funding more than doubled, from $13.7 billion to $28.6 billion. NIH funding has also increased significantly as a percentage of GDP. In 1950, NIH funding accounted for just 0.02 percent of GDP, while in FY 2013, it accounted for 0.18 percent. NIH funding in BRDPI inflation-adjusted figures and as a percentage of GDP peaked in FY 2003. FY 2003 was also a peak year for NIH funding as a share of the nondefense discretionary budget, when it reached a high of 6.9 percent.

NIH funding relative to BRDPI inflation, GDP, and the nondefense discretionary budget peaked in FY 2003, but since then has not fared well in real terms. While in nominal terms NIH’s funding grew by 15 percent between FY 2003 and FY 2010, that growth did not keep pace with overall inflation—meaning that the purchasing power of NIH funding decreased over that time. When adjusted for inflation, NIH funding decreased by 1.5 percent between FY 2003 and FY 2010. Moreover, when adjusted specifically for BRDPI inflation, NIH funding over that period decreased significantly by 11.4 percent.

In FY 2010, Congress embarked on a course of damaging austerity, ultimately resulting in sequestration in FY 2013. During this time period, nominal funding decreased by 6.7 percent. The effects were further exacerbated by the continually rising cost of biomedical research, which increased by 6.2 percent. The combined effect of austerity budget cuts and the increasing cost of biomedical research meant that between FY 2010 and FY 2013, NIH funding in BRDPI-adjusted terms decreased by 12.1 percent. Although President Barack Obama’s FY 2015 budget request calls for a slight nominal increase of 0.7 percent over FY 2014, it is expected to be too small to keep up with biomedical research inflation. This means that if Congress funds NIH at the level requested by the president, NIH’s purchasing power will decline yet again.

Where does NIH funding go from here?

The effects of the past decade of declining purchasing power for NIH funding will be felt over time because scientific discovery is cumulative. Just as research and development investments today will pay off down the road, missed opportunities in research and development support will be negatively magnified in the long run. That means that simply rolling back sequestration cuts will be insufficient to get NIH funding back on its historical BRDPI-adjusted funding track. Rather, new federal investments in NIH, over and above what was cut in sequestration, will need to be made in the coming years.

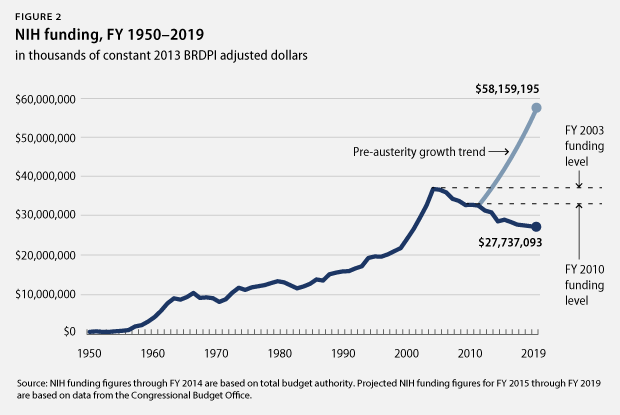

From FY 1950 through FY 2010, NIH funding grew at an average annual rate of 6.4 percent in BRDPI-adjusted figures. If instead of enacting austerity the federal government had continued to increase NIH funding along the same historical growth trend, NIH would have been funded at $42.6 billion in FY 2014, as opposed to the current BRDPI-adjusted funding figure of $29.6 billion. Extending this historical growth trend out to FY 2019, NIH funding in BRDPI-adjusted figures would equal $58.2 billion. Under sequestration, if NIH funding comprises the same share of nondefense discretionary spending as it does in FY 2014—6.1 percent—NIH funding in FY 2019 would be only $27.7 billion after adjusting for the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index.

As long as the spending caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 remain in place, it would be unrealistic to envision putting NIH funding back onto this long-term growth trend without crowding out other discretionary spending priorities. Yet even far more conservative scenarios would require significant increases in NIH funding in order to keep pace with the cost of biomedical research into the future. For example, the FY 2003 allocation for NIH represented a high watermark of bipartisan commitment to biomedical research that amounted to $37.5 billion in 2013 BRDPI-adjusted dollars.

Maintaining this level of spending through FY 2019 would require significantly higher funding levels than are currently projected under sequestration:

- Translating the FY 2003 funding level into nominal FY 2014 dollars would equal $38.2 billion—26.7 percent higher than the FY 2014 funding level of $30.1 billion.

- Translating the FY 2003 funding level into nominal FY 2019 dollars would equal $43.9 billion—35.1 percent higher than the FY 2019 projected funding level of $32.5 billion.

Maintaining an even more conservative funding level from FY 2010—the last fiscal year before austerity—would still require significantly higher funding levels than are currently projected under sequestration:

- Translating the FY 2010 funding level into nominal FY 2014 dollars would equal $33.8 billion—12.2 percent higher than the FY 2014 funding level of $30.1 billion.

- Translating the FY 2010 funding level into nominal FY 2019 dollars would equal $38.8 billion—19.6 percent higher than the FY 2019 projected funding level of $32.5 billion.

The impact of this research and development deficit will be immense in future years. The cumulative nature of biomedical research investment is such that every dollar invested today must be viewed through the lens of a considerably long time horizon. Many breakthroughs are the result of painstaking research that takes place over the course of years and decades. For example, 30 years of research elapsed between the key enabling discovery for the antidepressant Prozac and its introduction to the market. And 21 years elapsed between the key enabling discovery for the ovarian cancer drug Nolvadex and its introduction to the market. Therefore, the choice between more or less NIH funding today can mean the difference between whether or not scientists make a critical breakthrough several decades from now.

Congress failing to, at the very least, keep NIH funding on pace with the rising cost of biomedical research could result in less funding for researchers such as Anindya Dutta and others seeking breakthroughs in the treatment of diseases such as muscular dystrophy. Or it could mean the end of groundbreaking HIV research by Yuntao Wu of George Mason University.

Conclusion

NIH-funded biomedical research has played a critical role in improving the physical and mental health of Americans, which in turn has yielded significant societal economic benefits. The agency’s myriad successes—both in developing its own in-house research advancements and also spurring innovation and economic activity in the private sector—have engendered consistent levels of bipartisan support that have resulted in steadily increasing funding throughout the latter half of the 20th century. This federal funding has turned NIH into the cornerstone of an American biomedical research sector that leads the world in investment and innovation. The decisions of the past decade, however, have begun to threaten America’s pre-eminence in biomedical research. As NIH budgets began stagnating after 2003 and declining in 2010, the costs of conducting biomedical research continued to rapidly increase. As such, the lost purchasing power that NIH has experienced over the past decade cannot be undone by simply repealing sequestration. Rather, in order to secure America’s position as the global leader in biomedical research for the foreseeable future, Congress must pursue significant new investments above and beyond repealing sequestration.

Kwame Boadi is a Policy Analyst with the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress.

Author’s note: Inflation-adjusted and BRDPI-adjusted figures are in constant 2013 dollars. For purposes of consistency, historical budget comparisons omit the 1976 transition quarter.