As Congress digs into its fall legislative agenda, one important item of business it faces is which expiring tax provisions to extend and for how long. The release of federal poverty data this week is a reminder of the need to prioritize provisions that will help America’s working families struggling to get into or remain a member of the middle class.

Most of the expiring tax provisions expired at the end of 2014 and need to be extended before January 2016, when the 2015 return filing season begins. Several other provisions will expire in the next couple of years, including improvements to existing provisions that benefit low- and middle-income working families.

The logical approach to all of the expiring tax provisions would be to make permanent any that have both proven effective and been extended a number of times as a result. So far, the Senate has managed to sidestep this question. In July, the Senate Committee on Finance approved a bill that extends many already expired provisions for two years.

The House of Representatives, on the other hand, has passed bills that make selected expiring provisions permanent. Unfortunately, these bills strongly favor businesses at the expense of working families. The House voted to make permanent two expiring provisions that have obvious benefits for corporations and other businesses: the Research and Experimentation Tax Credit—more commonly referred to as the research and development, or R&D, credit—and Section 179 expensing. And now it looks like more business breaks may be coming, with the House Committee on Ways and Means marking up bills today that would make permanent three additional business tax breaks—bonus depreciation; the Subpart F exception for active-financing income; and the controlled foreign corporation, or CFC, look-through rule—that would cost an additional $345.6 billion over 10 years.

The R&D credit and Section 179 expensing

The R&D credit provides businesses a tax credit for increased investments in research and development over and above a base amount determined by averaging a firm’s research spending over the preceding three or four years, depending upon which method is used to calculate the credit. Its supporters, largely manufacturers, hail its economic effect and say it is needed in order to offset the high costs of R&D investments, which have spillover benefits for the economy—most directly, in the form of more jobs. But some studies have questioned whether the credit actually provides a significant incentive for companies to increase research spending and hiring beyond what they would have spent without the credit. While the R&D credit expired at the end of 2014, the House bill would not only make it permanent—it would expand the credit significantly, increasing its cost to the federal government by $72.6 billion compared to a permanent extension of the existing credit.

Section 179 expensing allows businesses to deduct the full cost of purchasing business equipment—such as large vehicles and machinery—in the year it was purchased rather than the normal tax treatment of deducting an asset’s cost ratably over its useful life. Because the deduction amount is capped, the provision has limited value for large businesses. In 2009, Congress increased the value of the deduction on a temporary basis—from $25,000 to $500,000 per qualifying depreciable property—as part of legislation responding to the Great Recession. Although it expired at the end of 2014, the provision allowing the larger deduction had been extended several times previously. Earlier this year, the House passed a bill that would make the $500,000 deduction permanent.

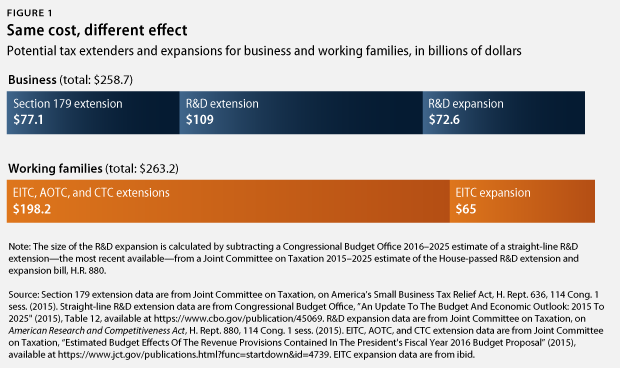

While both the R&D credit and Section 179 expensing have some merit as policy options, out of the more than 50 tax provisions set to expire, the House has cherry-picked these two for permanent extension while leaving untouched important provisions designed to help low- and middle-income families that the economic recovery has left behind. Moreover, the House has offered no plan to pay for the permanent extensions and expansions of either the R&D credit or Section 179 expensing, which, taken together, would cost the federal government $258.6 billion over 10 years. At the same time, Congress contends that budget deficits require them to slash spending on critical programs—such as affordable housing and infrastructure—to historically low levels. Clearly, Congress is out of balance in its priorities regarding expiring tax provisions.

Fortunately, Congress has great options available to protect tax provisions for struggling Americans. For roughly the same amount of money as the R&D credit and Section 179 extensions, Congress could permanently extend the 2009 temporary expansions of three tax provisions that benefit working families and their children.

The EITC, CTC, and AOTC

In 2009, Congress made temporary changes to the existing Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, and the Child Tax Credit, or CTC. It also enacted a temporary new tax credit for higher education called the American Opportunity Tax Credit, or AOTC. The EITC rewards low-income workers who have children with a refundable tax credit based on their income level and number of children. The 2009 law expanded EITC benefits for married couples and families with three or more children. Under the CTC, taxpayers may claim a partially refundable credit of $1,000 per child, and the 2009 bill expanded this benefit to very low-income families. The AOTC—which modifies the existing Hope credit still in law—helps defray the costs of higher education for more middle-income families than the Hope credit does and provides a larger amount of money, which can be claimed over all four years of a typical postsecondary education.

These 2009 expansions helped lift an additional 1.8 million Americans out of poverty and provided needed support for higher education, but they are all due to expire in 2017 unless Congress takes action. A further expansion of the EITC that was not included in 2009 but enjoys broad bipartisan support would make the credit available to childless workers.

Permanent extension of the 2009 modifications to the EITC and the CTC—as well as the creation of the AOTC and the expansion of the EITC to childless workers—would cost $263 billion over 10 years. This is roughly the same cost as the two permanent extensions the House has proposed for businesses.

An extensive body of research shows that the EITC is one of the most successful anti-poverty programs in U.S. history. The EITC and the similarly designed CTC increase workforce participation, work hours, and earnings, as well as decrease poverty. The AOTC is helping claimants from low- and middle-income families—83 percent of whom have adjusted gross incomes at or below $100,000 per year—afford college following an extended period of soaring tuition costs. Together, these provisions provide incentives to work, support for working parents, and greater opportunity for higher education. In fact, the refundable tax credits for working families have been so successful that the Center for American Progress has recommended building upon their success and expanding the CTC for low- and moderate-income workers with very young children. By contrast, corporations that make at least $250 million per year claim more than 83 percent of R&D tax credits.

Conclusion

The U.S. tax code is already skewed toward corporations and the wealthy. If Congress permanently extends and expands the R&D tax credit and Section 179 expensing for businesses, at a minimum, it should simultaneously extend and expand the 2009 provisions of the EITC, CTC, and AOTC for working families. Ideally, it should pay for all these provisions through reform elsewhere in the tax code. This could include repealing the carried interest loophole—which enables hedge fund managers to pay a lower capital gains tax rate on their ordinary income—and repealing the stepped-up basis rule that enables wealthy individuals to pass enormous amounts of capital income to heirs free of income tax. These changes would make the tax code fairer and ensure that everyone—not just a wealthy few—benefits from an improved economy.

Alexandra Thornton is the Senior Director of Tax Policy on the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Samuel Rubinstein was an intern with the Center and is currently studying economics at Brown University.