See also: Interactive: The Hidden Cost of a Failing Child Care System

The child care affordability crisis in the United States can be summed up in two sentences. Sixty-five percent of children younger than age 5 have all co-habiting parents in the workforce. The average annual cost to have two children in a child care center is nearly $18,000. This leaves many families to choose between spending a sizable portion of their paycheck on child care, finding less expensive—and possibly lower quality—unregulated child care, or leaving the workforce to become a full-time caregiver. This brief explores the financial toll that the latter decision places on families.

Yet the long-term cost can be much higher than these figures suggest when parents—and mothers in particular—find that expensive child care means they can barely afford to work until their children are old enough for public school. For most low-income and middle-class families, there is little government help with child care costs, but the cost of career interruptions can add up dramatically over a lifetime. Each year out of work can cost a family significantly more than three times a parent’s annual salary in lifetime income. Many low-income and middle-class families are stuck in a financial catch-22, with too little income today to afford child care that can sustain careers, raise incomes considerably, and provide a measure of financial security for the rest of their lives.

To help families calculate the financial costs of interrupting a career so a parent can become a full-time caregiver, the Center for American Progress has developed a simple, customizable interactive tool. The single most important contribution this tool makes, and the most important lesson for families using the tool, is placing these financial tradeoffs in the economic framework of opportunity costs, or costs people incur when they lose out on potential gains.

Child care is expensive, but quitting a job to avoid that expense does not make child care free. In fact, as explained later, the cost of so-called free care is much more than a parent’s lost wages. CAP’s tool calculates the monetary value of those costs in terms of potential income and retirement savings. These dollar figures are important for families and policymakers. The most important insight, however, is that any serious economic analysis of child care affordability must be rooted in opportunity costs. As trivial as this insight is in economics, CAP could not locate a tool to help families consider opportunity costs in choosing child care arrangements. The absence of such tools underscores that even with many families relying on all parents working and still feeling financially strained, American society still does not view giving families more child care choices as a serious economic issue. CAP hopes quantifying these large—and largely hidden—opportunity costs will help policymakers understand how important affordable high-quality child care is for raising family incomes and growing the economy.

The high cost of child care is well-documented. Previous research by CAP found that, for a typical middle-class family, child care costs grew by $2,300 between 2000 and 2012 while wages during the same time span remained stagnant. In all 50 states, the annual cost to enroll two children in a center exceeds median rent prices. In the majority of states, annual child care costs also exceed tuition and fees at an in-state university. Families living below the poverty line who pay for child care spend an average of 36 percent of their annual income on child care. The burden is not much easier for low-income families earning between 100 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty line, or the equivalent of $24,300 to $48,600 for a family of four who spend a sizable portion of their income on child care. With child care taking such a large bite out of earnings, it is easy to see how some parents—especially mothers in two parent families—can feel like leaving the workforce is not much of a choice.

Available data suggest that many families are opting to have a stay-at-home caregiver, usually the mother, in the face of exorbitant child care costs. A multidecade rise in mothers’ labor force participation peaked in 1999, when 23 percent of mothers did not work outside the home. However, the share of mothers not working outside the home rose to 29 percent in 2012. Child care costs also increased over the same time period. A 2015 poll commissioned by The Washington Post found that 62 percent of working mothers and 36 percent of working fathers switched to a less demanding job or stopped working altogether in order to care for children. The United States was once a leader in female labor force participation, but has fallen behind other developed countries in the past few decades. In 1990, the United States ranked sixth in female labor force participation among 22 industrialized countries. However, by 2010, the United States ranked 17th. Researchers estimate that about one-third of this difference can be attributed to family friendly policies in other countries, including child care spending by government and paid leave. This is not a symbolic issue; the increasing contributions of working mothers has been the key to stabilizing middle-class family earnings.

When parents leave the workforce, the long-term financial penalty can exceed annual child care payments, even with today’s high cost of child care. For some families, a full-time, at-home caregiver is an optimal and financially viable choice. But increasingly, single parents are the sole breadwinners and two-parent families need both incomes to make ends meet. In addition to lost wages, parents who interrupt their career earn less when they return to the workforce and those effects also reduce their retirement savings and social security benefits.

CAP research shows that workers can expect to lose up to three or four times their annual salary for each year out of the workforce. These losses add up because most parents have children when they are relatively young, so even a modest reduction in annual income can result in a very large lifetime earnings reduction over 30 years or more of work.

A woman earning the median salary for younger full-time, full-year workers—$30,253 annually in 2014—who takes five years off at age 26 for caregiving would lose $467,000 over her working career, reducing her lifetime earnings by 19 percent. A man in the same scenario—but earning the median wage for young male workers of $33,278 annually in 2014—would lose $596,000 over the course of his career and would see a 22 percent reduction in lifetime earnings.

Clearly, the U.S. child care system is broken. Not only do costs exceed what families can afford to pay, but many families also have difficulty even finding a child care program in their community. Researchers found that less than 10 percent of child care programs nationally are considered high-quality. Moreover, child care workers make dismally low wages for the difficult but important job of caring for young children during a developmentally critical period of their lives. Previous research has attempted to calculate the cost to the U.S. economy as a whole, finding that businesses lose more than $4 billion per year due to inadequate child care. But families pay a heavy cost as well. Described below are the ways in which families who opt out of the labor force bear the hidden costs of the lack of access to quality, affordable child care.

Why a child care calculator?

As high child care costs and families with all parents working have become increasingly common, new parents are frequently pushed to decide between continuing a career while paying child care costs or interrupting a career to provide care giving. There is a growing list of resources on the cost of child care in the United States, some, such as the U.S. Census Bureau’s report, “Who’s Minding the Kids,” focus on what families spend on any amount and kind of child care, while others, such as Child Care Aware of America’s report, “Parents and the High Cost of Child Care,” and the Economic Policy Institute’s report, “The Cost of Child Care in America” focus on the cost of full-time care. Those resources are extremely important for families seeking information about the cost of paying for child care, and they provide increasingly important context for policymakers. But the cost of providing full time family care is much more difficult to quantify, precisely because each person’s opportunity cost varies based on many personal factors. Helping families and policymakers understand these hidden costs is a crucial part of the conversation society needs to have about child care in America. To date, CAP has not identified a publicly available tool that calculates this cost for families.

The calculator developed by CAP begins to fill in that gap by demonstrating how interrupting a career is likely to impact families’ financial futures. Too often, policy discussions about child care treat parental choices as if they are unaffected by real life constraints. The assumption that parents who cannot afford child care can simply afford to stay home with children represents a failure to understand the fundamental economic tradeoffs families face. Moreover, this assumption is not true for single parents, who must find care in order to work and just as critically, the assumption is also not true of two-parent households when the hidden costs are counted. If interrupting a career to care for a child jeopardizes a parent’s retirement or means that a family cannot afford to send a child to college without borrowing heavily, this parental care is anything but free.

Scenarios not addressed by the calculator

It is important to note that this tool does not address three scenarios common to families: those that choose a full-time, at-home caregiver based on personal preference—as opposed to financial considerations; those that select lower-cost child care options; and those where one or both parents transition from full-time work to part time or self-employment.

Some families would prefer a stay-at-home parent, informal child care arrangements, or reduced hours even if finances were not part of the decision. But, for many families, short-term child care costs lead to arrangements that may not align with their immediate preferences or long-term interests. A resource such as this calculator is not focused on families who are making these choices independent of financial constraints. This tool focuses on the families for whom finances play a very large role in these decisions. The goal is to simplify the financially complex decision facing families and to help policymakers understand the real world tradeoffs these constrained families are locked into under the nation’s current child care system.

Some families might select informal child care arrangements or unregulated child care, that typically comes at a lower cost. This might include relatives or neighbors who are providing child care because of their relationship with the family. A subset of parents might prefer such arrangements, but the frequent use of unregulated child care is likely an indication that finances constrain choices for many families and that the nation is not providing families the tools to act in their long-term best interests.

All of these ad hoc workarounds have one thing in common: They avoid a concrete expense by trading away an uncertain cost. Some families choose lower-quality child care, which may reduce a child’s future earnings. Some families only consider jobs close to family members who can provide unpaid family care, but this constrains job opportunities and reduces earning potentials. Others provide family care themselves, even if it reduces their long-term earnings.

Calculating the cost of leaving the labor force

Economists consistently find that interrupting a career has long lasting effects on wages, even well after workers return to their career. Unfortunately, these insights have mainly informed economic and policy research. There has been little interest outside the field to help families understand the lifetime effects these decisions can have on earnings and retirement savings. The CAP child care calculator demonstrates how taking off a given number of years will affect lifetime finances. Moreover, the calculator was designed with families in mind. Such a design is a heavier lift than it may sound, and it is one reason this tool follows many of the cues of retirement calculators—which are one of the few tools for evaluating long-term financial tradeoffs consumers have experience with.

CAP estimates impact on family finances using data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, or NLSY79, using data from 1979 through 2012. We estimate the effects of experience and career interruptions on wages following a method developed in a 2005 paper by economist Christy Spivey with controls for education, demographics, and full- or part-time labor force status. This process is described in greater detail in the Methodology section of this brief.

The total lost income to households is reported in three components—a so-called rule of thumb lost wages, lost wage growth, and lost retirement assets. All figures are in today’s dollars, to control for inflation.

- The rule of thumb lost wages during a labor force absence is simply the worker’s last annual salary before taking leave multiplied by the number of years out of the labor force. This figure represents the cumulative earnings the worker would have earned had they remained in full-time work at the pre-leave salary. This calculation likely resembles the kind of calculation many parents might employ when considering the financial costs of leaving the labor force.

-

Lost wage growth reflects differences in estimated salary growth over time, after deducting employee 401(k) contributions. CAP assumes annual wage growth matches the mean effect of experience and nonexperience on real wages measured in the NLSY data assuming full-time, full-year employment, and reports the cumulative difference between the no-leave earnings profile and the leave earnings profile over time. This figure represents the additional income loss that the worker experiences after returning to the labor force full-time. The calculator deducts employee 401(k) contributions from wages, which are reflected in retirement assets.

-

Lost retirement assets includes two components, calculated based on the lost earnings and wage growth: savings from a traditional 401(k) account and Social Security. CAP assumes that 401(k) accounts yield a 4 percent annual real return until retirement, which is a conservative estimate. Users can set their 401(k) contribution rates; the calculator default is a 5 percent annual contribution from both the employer and the employee, which is chosen to match the median combined employer and employee contributions of program participants. CAP also determines Social Security benefits based on projected wages across the worker’s career and includes the difference in Social Security earnings in the retirement calculation for 15 years after retirement. Again, the assumption is conservative as life expectancies for retirees at age 65 is already longer than 15 years with today’s medical technology.

Results from this calculator also demonstrate that, for many Americans who are struggling financially, and even those in the middle class, a lack of affordable child care can be a much larger financial trap than commonly understood.

For many workers, this calculation shows the long run income gains from working significantly outweigh the cost of even very expensive child care. But because the costs of child care are concentrated in a few years, while the benefits in earnings are spread out over many years, most families simply cannot afford to pay for the child care they need to keep their careers going strong in their children’s early years. In real life, it is usually not possible to spend more than your income on child care for a period of years. Most parents who find themselves in that situation interrupt or reduce responsibilities in at least one career because they would run out of money before they could realize their long-term income gains from staying fully engaged.

Impact on families

Each family has different circumstances that will dictate the impact of time out of the workforce on their financial assets. The calculator is designed to take individual circumstances into account, including:

- Current salary

- Gender

- Age

- Age when the worker began full-time employment

- Age when the worker takes time off for child care

- Length of leave from workforce

No tool can adequately account for all individual circumstances that contribute to a family’s overall financial security when a parent leaves the workforce. This tool provides a useful figure for the hardest components to estimate in this calculation, but families should supplement this knowledge with additional information specific to their circumstances.

The lifetime cost of taking many years out of the labor force is significant, but the alternative is not free. Families must factor in the cost of care they will use, as well as the costs incurred while working—commuting costs, for example—and the additional taxes they will pay and benefits they may lose.

From an economic policy perspective, pre-tax income is the measure of the economic effect of additional family income on gross domestic product, or GDP. However, when families are making these decisions themselves, their marginal tax rates will have significant effects on the lifetime earnings differences, especially for high-income families or families who currently qualify for means-tested benefits. Determining a family’s effective marginal tax rate would require much more information than this calculator collects, but it is an important component of the child care tradeoff families should consider in addition to information presented in this calculator.

The hypothetical examples below highlight the projected impact on workers in specific scenarios. It is important to note that these are projections based on average effects of a simplified model, which cannot predict each individual’s actual career and earnings path. There are a host of important factors beyond the scope of this simple tool that impact individual earnings. It is also important to note that this tool provides a much more accurate characterization of the effects of career interruptions on earnings than families today have to work with.

Examples

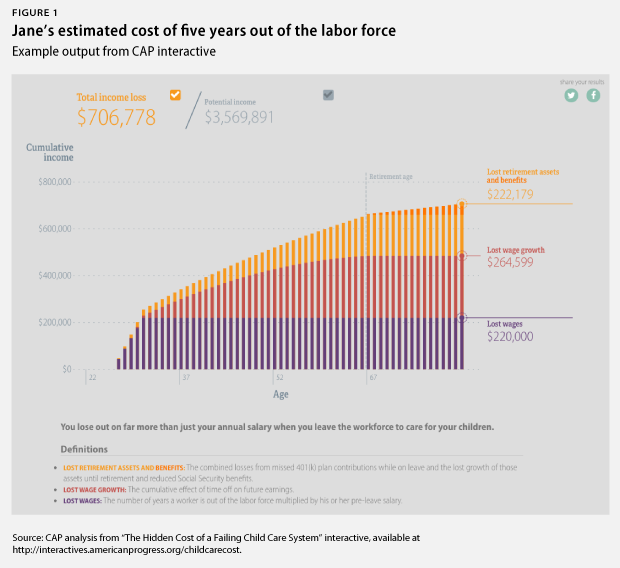

Jane is a middle-class worker with a job as a first-grade teacher. As a relatively new teacher, her salary is at the 25th percentile for elementary school teachers in the United States and she earns $44,000 annually. She has a baby when she is 26 years old, the average age of a first-time mother in the United States. Jane is deciding whether to leave the workforce until her child enters kindergarten or remain in the labor force and find child care.

During the five years that Jane is out of the labor force, she will lose her $44,000 salary each year, so a simple estimate of the opportunity cost of caring for her child until kindergarten is $220,000. This number, however, misses the totality of what Jane might lose; this is what the calculator is designed to capture. A five-year career interruption means Jane will lose out on an estimated $265,000 in lifetime wage growth, plus another $222,000 in retirement benefits.35 In fact, we estimate that taking five years off will cost her nearly $707,000, in today’s dollars, over her lifetime—or roughly 3.2 times as much as her lost wages alone.

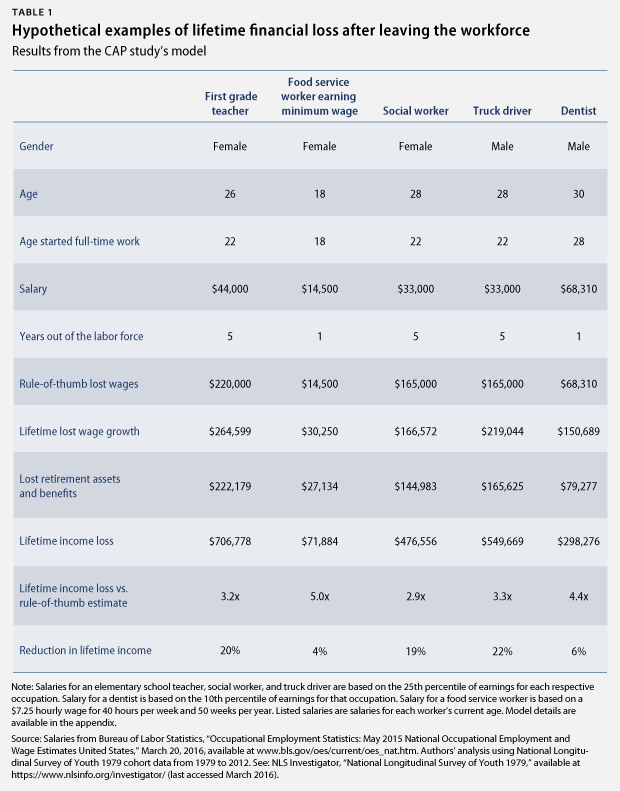

Table 1 provides additional illustrative examples. While financial loss varies by worker, in each case the lifetime income loss is much higher than just earnings lost. In fact, these workers lose between two and four times their annual salary when they leave the workforce.

Though the numbers are quite large, they align with what is understood about personal finances. Income losses are largest for high earners who take many years off. Less obviously, but still intuitively: having a child later reduces the lifetime cost of career interruptions. Someone who works from age 25 to age 67 and takes two years off at age 30, for example, would see his or her wages reduced for 35 years, but taking two years off at age 40 means wages are only reduced for 25 years. The other important driver is Social Security benefits, which replace a larger fraction of a low-income worker’s income. This is one reason that the ratio of lifetime income loss to lost wages is highest for low-income workers.

These hypothetical scenarios are akin to the decisions facing real families every day, and the stakes are much higher than policymakers often assume. Middle-class families make few decisions worth hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of their lifetime, yet today families make this decision without a common framework for understanding the full effects of child care decisions—assuming they have the resources to afford the high cost of child care in the short term at all. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, defines affordable child care as constituting no more than 10 percent of household income.37 In the scenarios above, the nearly $18,000 price tag for two children in a child care center exceeds what most of these workers can reasonably afford with 10 percent of their income. Many low-income and middle-class families are stuck in a financial catch-22, with too little income today to increase their incomes in the future.

The policy solution

Most families cannot absorb the high cost of child care while maintaining their careers, nor can most parents afford to leave the labor force. The likely result of this financial strain on families today is an underinvestment in high-quality child care—the very type of child care that will produce benefits to all Americans for decades to come. The United States should follow the lead of other industrialized countries and make child care assistance and other family-friendly policies the norm. A study commissioned by the Department of Labor estimated that if strengthening work-family policies to match other advanced economies resulted in similar levels of women’s labor force participation, the United States would see an additional 5 million women in the labor force and $500 billion in increased GDP. Today, women consistently earn the majority of college degrees, while also remaining more likely to interrupt a career. The costs of these interruptions to families and the U.S. economy, therefore, are set to rise even further over time.

Earlier this year The Center for American Progress proposed a High-Quality Child Care Tax Credit that would help parents afford high-quality child care.40 The tax credit provides up to $14,000 per child for families earning up to 400 percent of the poverty level, or $97,000 annually for a family of four. Families contribute between 2 percent and 12 percent of their income on a sliding scale. The credit would be advanced during the year so that families have resources upfront to pay for child care, rather than wait until their tax return the following year. To ensure that low-income families can benefit from the program, the tax credit would be refundable.

Conclusion

Affordable, high-quality child care is a pressing financial issue for families and the U.S. economy. It is also an issue that politicians frequently shrink from due to the perception that these programs are unaffordable—even when the lack of these programs can be many times more expensive. When parents do not have the resources to afford high-quality child care, families pay in the short term and pay even more in the long term. Society also pays in the long term, in the form of increased financial stress in families, slower economic growth, lower labor force participation—especially among women, and fewer qualified workers. It is time to make investments that pay off for two generations by making high-quality child care affordable for all. Ample research shows the future workforce benefits from early investments in education. But these investments also create meaningful choices for parents, give parents the opportunity to make financial decisions that pay off in the short and long term, and provide real economic security for working families.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at American Progress. Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the Economic Policy team at American Progress. Katie Hamm is the Senior Director of Early Childhood Policy at American Progress.

The Methodology section is included in the PDF version of this report.