It is no secret that annual appropriations bills are often used as a vehicle for moving through discrete legislative measures unrelated to funding the government. Because appropriations bills are often considered to be “must pass” pieces of legislation, packaging nonfunding policy provisions into these bills can be an effective way to ensure passage of measures that might not pass if submitted through the regular legislative process in the House and Senate.

The use of appropriations riders to enact policy changes, however, has reached new heights in the area of firearms. Beginning in the late 1970s and accelerating over the past decade, Congress, at the behest of the National Rifle Association, or NRA, and others in the gun lobby, began incrementally chipping away at the federal government’s ability to enforce the gun laws and protect the public from gun crime. The NRA freely admits its role in ensuring that firearms-related legislation is tacked onto budget bills, explaining that doing so is “the legislative version of catching a ride on the only train out of town.”

Inserting policy directives in spending bills bypasses the traditional process, which allows for more careful review and scrutiny of proposed legislation. Appropriations bills are intended to allocate funding to government agencies to ensure that they are capable of fulfilling their missions and performing essential functions. But the gun riders directed at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF, do exactly the opposite and instead impede the agency’s ability to function and interfere with law-enforcement efforts to curb gun-related crime by creating policy roadblocks in service to the gun lobby. As a group, the riders have limited how ATF can collect and share information to detect illegal gun trafficking, how it can regulate firearms sellers, and how it partners with federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

The Obama administration has, at times, recognized the problematic nature of such policy-directed appropriations riders. In May 2012 President Barack Obama threatened to veto the appropriations bill to fund the Department of Commerce, the Department of Justice, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation, and other related agencies for fiscal year 2013—in part because of the inclusion of this type of policy rider. The president specifically mentioned a rider aimed at ATF that sought to prohibit the agency from requiring firearms dealers in four border states to report the sale of multiple rifles or shotguns to a single individual—a new policy that had been implemented to assist law enforcement fighting illegal gun trafficking along the border with Mexico. Calling such riders “problematic policy and language riders that have no place in a spending bill,” the Obama administration stated that it “strongly oppose[d]” this type of rider.

The tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, last December, coming on the heels of a string of other recent mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado, and Tucson, Arizona, has proven to be a wake-up call to the American people that the issue of gun violence in this country must be addressed. The president and many members of Congress have taken up this charge for the first time in many years. Outside Capitol Hill, it’s evident that a serious and comprehensive discussion about how to prevent gun violence in our communities has begun, both on questions of legislation and executive action. Thus far, the debate has focused primarily on major legislative proposals such as universal background checks, a renewed assault weapons ban, and increased penalties for gun traffickers. These measures are critically important to reducing gun violence, but the discussion should not end here. As examined in detail below, there are more than a dozen appropriations riders passed each year, typically without any discussion or debate, which significantly limit the federal government’s ability to regulate the firearms industry and fight gun-related crime. These riders jeopardize public safety and and threaten to undermine any new legislation that Congress may pass to reduce gun violence.

Among other things, these riders:

- Limit ATF’s ability to manage its own data in a modern and efficient manner, and strip the agency of autonomy and its ability to make independent decisions

- Interfere with the disclosure and use of data crucial to law enforcement and gun-trafficking research

- Frustrate efforts to regulate and oversee firearms dealers

- Stifle public health research into gun-related injuries and fatalities

As President Obama stated in January 2013 while unveiling his proposals to reduce gun violence:

While there is no law or set of laws that can prevent every senseless act of violence completely, no piece of legislation that will prevent every tragedy, every act of evil, if there is even one thing we can do to reduce this violence, if there is even one life that can be saved, then we’ve got an obligation to try.

In the discussion that follows, we call on President Obama to remove all of the unnecessary and dangerous riders from the fiscal year 2014 appropriations bill he will submit to Congress. Removing these riders has the potential to free the ATF and other federal agencies to use their substantial knowledge and expertise to protect our communities from future gun-related tragedies. In his first budget proposal to Congress since the Newtown shooting, we urge the president to introduce a clean budget that strips each of the riders described in detail below from his FY 2014 budget. The president can lead with a clean budget, but ultimately Congress must act. Therefore, we call on Congress to have an open debate about the unnecessary and dangerous restrictions contained within this set of policy riders.

Limits on ATF management and operations

Unlike other federal law enforcement agencies that are afforded a high level of organizational autonomy and given wide latitude to develop programs and systems to facilitate their mission, ATF’s activities are tightly controlled by Congress. Over the years, Congress has imposed numerous restrictions on how ATF manages its data, whether or how it acts to fulfill its duties under various laws, and its ability to delegate any of its functions to other agencies or departments.

Data management

Since 1979 the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has been prohibited from creating a centralized database of gun sales records already in its possession. While federal firearms licensees are required to keep records of every firearm sale they engage in and to provide this information to ATF upon request—for example, to assist police by tracing a gun found at a crime scene—ATF is not permitted to consolidate that information into a centralized database that could be easily accessed by law enforcement when a gun is recovered at a crime scene. ATF is also restricted from putting records of gun sales obtained when dealers go out of business into an electronic, searchable database. ATF receives an average of 1.3 million records from out-of-business dealers each month, and it is forced to keep these records in boxes in warehouses or on microfiche.

A centralized database containing this type of data bears no resemblance to a registry of gun purchases as the gun lobby claims. Creating such a registry, or even maintaining data for approved gun background checks indefinitely, is expressly prohibited by the Brady Act, which created the firearm background check system. Instead, these riders restrict how ATF accesses records it is already entitled to access and maintains records already in its possession. Because there is no centralized electronic database of gun records already in its possession, when a gun is found at a crime scene, ATF is forced to go through a complicated and time-consuming process to try to determine the gun’s owner. ATF agents must sift through hundreds of thousands of paper records, make numerous phone calls to the manufacturer and retail dealer that first sold the weapon, and rely on records kept by federally licensed firearms dealers to attempt to identify the weapon’s owner. Using this antiquated and inefficient system, a firearms trace can take days, or even weeks, thereby frustrating criminal investigations. Considering that ATF conducted more than 333,445 firearms traces in 2012, the amount of time, effort, and resources that could have been saved had ATF been able to simply search its own records is truly staggering.

Since 2004 Congress has included another gun rider—one of the so-called Tiahrt Amendments, after their chief proponent, former Rep. Todd Tiahrt (R-KS)—to the appropriations bill that directly impedes law enforcement’s ability to identify straw purchasers—a person who buys a gun for someone who can’t legally purchase a gun—and criminal gun-trafficking networks. Pursuant to this rider, the FBI may only retain records of individuals who successfully passed the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, or NICS, for 24 hours.

The destruction of these records means that federal law enforcement is deprived of the opportunity to recognize patterns in apparently legal gun sales that suggest straw purchasing and gun trafficking. Federally licensed gun dealers, for example, are required to report to ATF when an individual purchases more than two firearms in a five-day period because such sales raise a red flag that the individual may be engaging in straw purchases or gun trafficking. But straw purchasers can easily evade detection and bypass this reporting requirement by purchasing smaller quantities of guns from multiple dealers, knowing that law enforcement will not be able to track these purchases because the federal background check records will be almost immediately destroyed. The destruction of these records within 24 hours also deprives ATF of the opportunity to proactively identify corrupt gun dealers who falsify their records to enable straw purchases. Instead, ATF is not alerted to criminal activity engaged in by licensed gun sellers until after crimes are committed and the guns used in those crimes are traced back to the corrupt dealer—by that time it is too late to prevent harm to public safety.

When the National Instant Criminal Background Check System was first created, the FBI was permitted to keep records of individuals who passed a background check for six months so the system could be audited to ensure that it was not being used for unauthorized purposes, and to enable other quality control checks. The FBI subsequently revised the applicable regulation to shorten the permissible retention period to 90 days. These multimonth retention periods were upheld by federal courts as consistent with the prohibition in the Brady Act on creating a registry of firearms. Congress should remove this rider and allow the FBI to revert to the three-month retention period to give law enforcement the opportunity to mine these data for indications of criminal activity and ensure that the background check system is functioning properly and not being misused.

The practical result of these appropriations riders intended to prevent a speculative and unfounded fear of widespread firearms confiscation is to impede law enforcement investigations into violent criminal activity and needlessly waste already limited ATF resources. Each of these riders should be stripped from the FY 2014 appropriations bill so our federal law enforcement agencies can take the steps necessary to modernize their data collection and management systems and pursue criminal investigations more efficiently.

Basic operations

Congress has also imposed riders that strip away ATF’s autonomy as an agency and impose arbitrary restraints and conditions on its activities. The most drastic of these measures is a rider first added in 1994 that prevents ATF from transferring any of its “functions, missions or activities” to another agency or department. As a consequence the Department of Justice is prohibited from moving certain law enforcement functions of ATF to the FBI, where there are more resources and a more developed leadership structure. Such shuffling of responsibilities among subordinate entities is routine at other agencies and in the corporate world, yet the Department of Justice is denied the opportunity to engage in this basic management practice, even in the face of repeated criticism from Congress about inefficiencies and mistakes at ATF. ATF faces serious challenges to its ability to effectively fulfill its mission—including Congress’ failure to approve a permanent director for the past six years—yet is prohibited from taking steps to address these challenges in any meaningful way. Instead of giving flexibility to federal agencies to cooperate, share resources, and work together more efficiently, with this rider Congress has instead frozen in place ATF’s ability to partner with and seek aid from other federal law enforcement agencies.

Limits on the disclosure and use of trace data

In 2004 a set of appropriations riders collectively known as the “Tiahrt Amendments” were tacked onto the Department of Justice appropriations bill. Among other things, these riders drastically limited the ability of ATF and other law-enforcement agencies to use and disseminate trace data—data that links guns found at crime scenes to a manufacturer, the dealer that originally sold it, and possibly the identity of the owner.

The Tiahrt trace data rider barred ATF from disclosing any trace data to the public, shielded trace data from subpoena in civil actions, and provided that these data are inadmissible in evidence. In their original form, the riders also limited the access of law-enforcement agencies to data related only to a particular criminal investigation and pertaining only to their geographic jurisdiction, which prevented police from obtaining batch data that could help identify straw purchasers, problematic gun dealers, and illegal gun traffickers operating across state lines.

These provisions were introduced at the behest of the NRA in large part to shield the firearms industry from lawsuits that municipalities had begun to file alleging negligent practices that allowed guns to end up in the hands of criminals. Tiahrt himself acknowledged what motived him to pursue these riders, explaining, “I wanted to make sure I was fulfilling the needs of my friends who are firearms dealers.”

These riders limiting access to and use of trace data proved to be a danger to public safety. Research conducted by a team at the Johns Hopkins University analyzed the impact of these appropriations riders on the diversion of guns to criminals by one of the nation’s leading suppliers of guns used in crimes, Badger Guns & Ammo in Milwaukee. According to ATF data, in 1999 Badger Guns & Ammo had the highest number of sales of guns that were later recovered at a crime scene. The Johns Hopkins research found that, following the passage of the Tiahrt Amendments, the number of guns sold by Badger Guns that were later discovered at a crime scene increased by 203 percent. The study’s authors attributed this increase to the riders, stating that these provisions “prompted a dramatic increase in the flow of guns to criminals from a gun dealer whose practices have frequently been of concern to law enforcement and public safety advocates.”

After campaigns by hundreds of mayors and police chiefs, some of the worst gun-trace data restrictions have been amended. ATF is now permitted to release annual statistical reports containing aggregate trace data and law-enforcement agencies are free to receive trace data regardless of whether the data requested pertains to a particular investigation or the geographic jurisdiction of the agency asking. Yet the remaining restrictions on the disclosure of trace data continue to pose significant obstacles to law enforcement and efforts to stop corrupt gun dealers from illegally selling weapons to criminals and gun traffickers. The prohibition against using trace data in civil proceedings means that evidence of a gun dealer’s frequent sale of guns that end up at crime scenes—a strong indicator of malfeasance by the dealer—may not be used in a state or local proceeding to revoke the dealer’s license. Additionally, the limitation on ATF’s ability to release any but the most aggregated trace data to the public means that criminal justice researchers are unable to put their substantial expertise to use identifying complicated interstate and international gun-trafficking patterns.

Oversight of gun sellers and gun manufacturers

One of the most important functions of ATF is to regulate and oversee the firearms industry. ATF is the licensing body for firearms dealers and is responsible for ensuring that federally licensed firearms dealers comply with the laws and regulations that govern their businesses. This work is vitally important, as incompetent or unscrupulous gun dealers create an opportunity for guns to be diverted out of the lawful stream of commerce and into the hands of dangerous individuals and criminal gun-trafficking networks. Once again, Congress has interfered with ATF’s ability to fulfill its mission by enacting riders to the appropriations bill that dilute its power over licensed gun dealers.

Oversight of federal firearms licensees

ATF’s primary tool to ensure compliance with federal laws and regulations is to conduct regular inspections of federally licensed firearms dealers. Yet current resource limitations make it impossible to regularly inspect the roughly 60,000 gun dealers in the United States. With only around 600 inspectors available to conduct these inspections—inspectors who must divide their time between prospective dealers, explosives retailers, and active gun dealers—the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives is currently only able to inspect licensed gun dealers about once every five years.

One of the most important parts of an ATF inspection of a federally licensed firearms dealer is an inventory check to ensure that the dealer can account for every gun that has passed through its doors. In the event that dealers cannot account for large numbers of guns that should be in their inventory, a red flag is raised to the ATF that illegal guns sales may be occurring. Additionally, guns reported as lost or stolen end up at crimes scenes in large numbers, indicating that this is a common way for guns to be diverted into criminal hands. One way to fill the gap in the infrequent inspections is to require gun dealers to regularly check their inventory against their sales to ensure that all guns are accounted for. Because licensed gun dealers are required under federal law to report lost or stolen guns to the ATF, keeping an inventory would be an effective way of ensuring that missing guns are promptly identified and reported to law enforcement.

The utility of requiring gun dealers to keep an inventory was recognized in the late 1990s when research revealed that a small fraction of gun dealers were the first sellers of the majority of guns recovered at crime scenes. As a follow-up to this research, ATF began focusing inspections on these problematic dealers and found rampant illegalities, including missing guns, noncompliant record-keeping, and hundreds of firearm sales to prohibited purchasers. In response, the Clinton administration proposed requiring gun sellers to keep an updated inventory to ensure that each firearm was properly accounted for.

In 2004 the NRA and others in the gun lobby shut down these efforts to rein in the problem of gun dealers failing to maintain control of their inventories by including a provision in the package of Tiahrt amendments that specifically prohibits ATF from requiring dealers to conduct an annual inventory. A business practice that is routine and uncontroversial in nearly every other retail market, including the retail market for explosives, which is also overseen by ATF, is banned by the federal government in the context of the sale of one of the most dangerous consumer products.

This is not an idle concern. During the inspections that ATF is able to conduct with its limited resources, tens of thousands of guns are discovered to be lost or stolen each year. In 2011 ATF discovered that nearly 18,500 guns were unaccounted for during the course of 13,100 firearms compliance inspections. In 2012 the inspection of just one gun dealer revealed that 997 guns were unaccounted for and an additional 93 guns had not been logged in as inventory, a sign of illegal sales. Guns lost or stolen from dealer inventories have been found at high-profile shootings, such as the Washington, D.C.-area sniper shootings in 2002. One of the guns used in that string of murders disappeared from the inventory of Bull’s Eye Shooter Supply in Tacoma, Washington, which had lost track of 238 guns over a three-year period. Additionally, Riverview Sales, the gun dealer from which the Newtown shooter’s mother legally purchased the guns used in that attack, has a history of losing track of weapons in its inventory and gun thefts by employees and customers. ATF has commenced proceedings to revoke its federal firearms license.

The NRA argues that requiring licensed gun dealers to maintain an inventory would be unduly burdensome on law-abiding dealers. But maintaining accurate inventory records is a routine business practice in nearly every other retail industry and any burden on lawful dealers—who are likely already keeping these records as part of a good business practice—is outweighed by the benefit to public safety of quickly identifying missing guns and reporting them to law enforcement. An inventory requirement would also serve as a deterrent to gun dealers tempted to break the law by selling guns to criminals, as well as an incentive to law-abiding firearms dealers to ensure that they are in full control of their dangerous inventory.

Congress has also imposed another limitation on ATF’s ability to regulate gun dealers via appropriations rider. Since 2004 ATF has been prevented from denying or refusing to renew a gun dealer’s license for “lack of business activity.” This means that, despite the requirement under federal law that a gun dealer be “engage[d] in the business” of selling guns, any individual may obtain a federal firearms license, regardless of the size of their business or the frequency with which they sell guns. This has the effect of undermining the licensing requirements and creating a glut in the licensee population, which makes it harder to regulate. ATF should be given the discretion and autonomy to enforce the federal laws as it deems appropriate and this kind of policy decision should be left to the agency, not made in a vacuum by Congress during budget negotiations.

Regulation of firearms

In addition to regulating federal firearms licensees, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives also has the authority to enact regulations to facilitate the enforcement of other federal firearms laws, including the Gun Control Act, the National Firearms Act, and the Arms Export Control Act. Congress has once again cut the agency off at the knees in its attempts to do so, enacting even more appropriations riders that limit the agency’s ability to function and impose policy decisions that are better left to the agency to make.

This can be seen in the fact that since 1996 ATF has been banned from changing the definition of what firearms constitute “curios or relics.” Under current federal regulations, curios or relics are defined as firearms “which are of special interest to collectors by reason of some quality other than is associated with firearms intended for sporting use or as offensive or defensive weapons.” Any firearm that was manufactured at least 50 years ago qualifies as a curio or relic, as well as others of museum interest or that are otherwise rare or novel. Curio and relic firearms occupy a unique place in the federal firearms licensing scheme. Individuals can obtain a collectors firearms license from ATF that allows them to buy and sell curio and relic firearms in interstate commerce—particularly online—without going through the federal firearms licensing procedure and without the requirement of a national instant background check. Constraining ATF’s ability to evaluate the guns receiving curio or relic classification and requiring that the current definition remains unchanged means that there are dangerous, serviceable weapons in our communities, including some semiautomatic military surplus rifles manufactured only 50 years ago, which are subject to far less stringent regulations than comparable modern weapons. These are not merely antique guns that are locked away in display cases—modern semiautomatic rifles such as the SKS and Dragunov SVD currently qualify as curios and relics. What’s more, so-called curio and relic guns have been used in crimes in the United States. Case in point: In 2011 a teenager in New Mexico was charged with murdering his father by shooting him with a “Russian war rifle from 1936.”

This rider is also particularly problematic because the overuse of the curio and relic classification has led to circumvention of the ban on the importation of assault rifles enacted by President George H.W. Bush. While attracting less attention than the federal assault weapons ban, the 1989 ban on the importation of “non-sporting purpose” firearms is still in force and is intended to block the importation of assault rifles. A curio and relic classification means that assault rifles of particular makes and models—even those manufactured in the last several years—are exempt from the ban.

Another example of congressional overstepping in the area of firearms regulation is a series of riders that limit the ability of various government agencies to regulate the international trade in firearms. Congress has imposed bans on denying applications to import curio or relic firearms and certain models of shotguns. These prohibitions limit ATF’s ability to minimize the risk of certain dangerous, serviceable weapons entering the United States and potentially ending up the in the hands of criminals. Congress has also imposed a ban on requiring an export license for exporting certain firearms and accessories to Canada, a measure designed to facilitate hunting between the two nations. But here again, regardless of the intent of these appropriations riders, policy decisions such as these are best left for the experts at ATF and other agencies to make after careful study and consideration, not imposed by Congress during the budget process at the urging of the gun lobby.

Hampering public health research

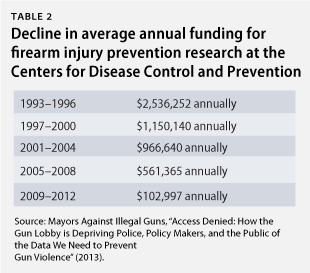

Congressional stifling of federal activities regarding firearms through the vehicle of appropriations riders extends beyond law-enforcement agencies and affects public health and research as well. Congress has essentially silenced any federal public health research into firearms injuries by inserting language into the appropriations bill prohibiting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health from spending any funds to “advocate or promote gun control.” Proponents of these riders, chief among them the NRA, argue that gun violence is a law-enforcement issue and research institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should not be participating in policy debates. Mayors Against Illegal Guns recently issued a report conducting an in-depth analysis of how these riders and other measures have strangled nearly all federal research into firearms. While these riders are not an overt ban on studying firearms injuries or deaths, it has been perceived by the agencies as a threat that any such research will result in a loss of funding and has therefore had a chilling effect. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding for firearms injury prevention research has fallen 95 percent since this appropriations language was added—from an average of $2.5 million annually between 1993 and 1996, to around $100,000 annually in 2012. Without the benefit of up-to-date public health research into gun violence and gun-related injuries and deaths, legislators and policymakers are left to guess which proposals will be most effective at addressing these issues.

As part of his comprehensive plan to address gun violence, President Obama recognized the importance of public health research on gun violence and condemned the congressional actions attempting to limit it. He asserted that such research is not, in fact, advocacy and is not prohibited by any appropriations language. The administration has directed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to recommence research into the causes and prevention of gun violence. This is a good start toward freeing public health research institutions to devote attention to gun violence, however, these riders must be stricken from the appropriations bill to remove any doubt that this type of research constitutes a permissible use of funding. It is also worth noting that these riders are unnecessary and duplicitous, as these and other federal research institutions are already prohibited from engaging in political advocacy under the Hatch Act.

Permanently hamstringing federal action on guns

Not only has the NRA succeeded in adding these provisions into appropriations bills, in many cases they have succeeded in including language that gives the provisions future effect beyond the period for which funds are being appropriated. Typically, because appropriation legislation provides funding for a particular fiscal year, the presumption is that the provisions contained in these bills apply only to that year and are not intended to be permanent. But if Congress uses so-called “words of futurity” that indicate the intent to make the provision permanent, it will be considered permanent law.

Some of the appropriations riders discussed above have been made permanent using such futurity language, such as the prohibition on creating an electronic database of gun sales records and the requirement that records from national instant background checks be destroyed within 24 hours. The campaign to make these riders permanent continues even in the midst of the debate over other gun-related legislative measures. The continuing resolution being debated during the week of March 11, 2013, to fund the government through the end of this fiscal year includes language making permanent the riders prohibiting ATF from requiring gun dealers to keep an inventory, restricting ATF’s ability to change the definition of curio and relic firearms, preventing ATF from denying or revoking a federal firearms license for lack of business activity, and an additional rider that requires ATF to include a disclaimer on the conclusions that may be drawn from trace data in any report. For those riders that have been made permanent, it will not be sufficient to simply omit them from future appropriations bills. Instead, affirmative language will be needed in the FY 2014 bill to override the future effect of many of the riders included in prior budgets.

Conclusion

On many occasions the leadership of the NRA has claimed to support vigorous enforcement of the gun laws on the books. By way of illustration, during his recent testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Wayne LaPierre, CEO and executive vice president of the NRA, said, “We support enforcing the federal gun laws on the books 100 percent of the time against drug dealers with the guns, gangs with guns, felons with guns. That—that works.” Despite this rhetoric, no organization has done more to inhibit the law-enforcement functions of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and other federal agencies than the NRA. No other area of federal law enforcement suffers from so many legislative barriers to action. It’s time to start with a clean slate. It’s time for President Obama to lead by delivering to Congress a budget that removes these unnecessary and dangerous riders and cancels the future effect of riders included in prior budgets.

Winnie Stachelberg is the Executive Vice President for External Affairs at the Center for American Progress. Arkadi Gerney is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Chelsea Parsons is the Associate Director of Crime and Firearms Policy at the Center.