U.S. economic growth in the third quarter of 2013 plowed forward at 2.8 percent, though the surge was driven almost entirely by an accumulation of inventories, which added 0.8 points to the headline growth rate, according to new data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Underlying noninventory growth remained steady and too slow at just a 2 percent rate.

This release of data on U.S. gross domestic product, or GDP—the sum total of all goods and services produced by workers and equipment in the United States—reports on the overall progress of the U.S. household, business-investment, and trading sectors of the economy. But the big news in today’s report is the rapidly shrinking economic contribution of the public sector, which is driving not only trend U.S. economic growth lower but also our potential for future growth.

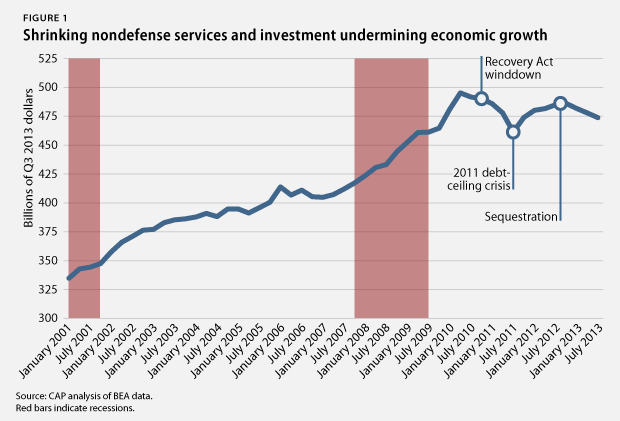

Today’s numbers look back to where the U.S. economic recovery was in September 2013—before conservative lawmakers shut down the federal government and threatened financial default in October over health care reform, but at the peak of their nearly three-year crusade forcing sharp cuts in public spending since Republicans took control of the House of Representatives in 2011. The result has been a sharp contraction in economic contributions from spending on public services and investment, which shrank 1.7 percent at the federal level after shrinking 1.6 percent in the second quarter. Federal nondefense discretionary spending—which the October government shutdown impacted the most—in the nine months through September had already decreased 2.5 percent after inflation.

Since the end of 2010, shrinking overall government investment and public services have subtracted on average nearly 0.5 percentage points from the U.S. growth rate—or about $195 billion in total, according to today’s data. This damage compounds atop costs that Macroeconomic Advisers estimates at 0.3 percentage points of growth per year and 900,000 lost jobs from economic uncertainty due to political obstruction.

Public spending and investment are not merely a matter of Keynesian “ditch-digging” to temporarily boost demand in the economy—they have a critical impact on the economy’s supply-side growth too. Federal Reserve economists estimate in recent research that current supply-side growth is running about 7 percent below the trajectory prior to 2007. A significant portion of this damage to U.S. economic prospects was due to the weakness in aggregate demand—the spending by households, businesses, and government.

During the shutdown, many Americans relearned how government plays a fundamental role in a vibrant economy—supplying critical services on which businesses and investors rely, maintaining a competitive modern infrastructure, and fueling innovations in medicine and other fields of technology. Normally, one might expect the demand for public services to grow proportionate with population and the size of the economy—as it basically did throughout the economic expansion in the 2000s and the first phase of the Great Recession. (See Figure 1) But then the Recovery Act and related stimuli started winding down in December 2010, with 80 percent or more of the spending expiring. Things went downhill fast in 2011 and after—plunging first with the 2011 debt-ceiling standoff and bending down again as political stalemate failed to stop the sequester.

The continued political drive for spending cuts does not portend well for the United States’ ongoing efforts to recover from the Great Recession and to retool growth for a more globally competitive and broadly prosperous economy. This is not a partisan conclusion: In a recent statement, the Business Roundtable called on Congress to replace sequestration’s crude automatic spending cuts with smarter policymaking that does not risk growth. Last year, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce warned that sequestration would “wreak havoc” on the U.S. industrial base and national economic security. Nonresidential business investment slowed to 1.6 percent this quarter from 4.7 percent the previous quarter, according to today’s seasonally adjusted data.

Congress could eliminate this fierce headwind on economic recovery today with the flick of its gavel by replacing future sequester cuts with a growth-oriented approach to managing U.S. financial sustainability.

Adam S. Hersh is an Economist at the Center for American Progress.