This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

The employment report for March, released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS, on Friday, brought a cautiously upbeat labor market back down to earth. Even as many other economic indicators have been slowing, the labor market had been showing strong progress in 2015. But in March, well, not so much. In fact, not only was the data for March disappointing—the unemployment rate was flat at 5.5 percent and the economy added just 126,000 jobs—but the news for the prior two months ended up being not nearly as rosy as previously thought. The U.S. economy created 69,000 fewer jobs in January and February than originally reported. That said, the overall trend in job creation remains fairly strong, but given all the slack in the labor market, markets can be forgiven for questioning the Federal Reserve’s claims of impending rate hikes.

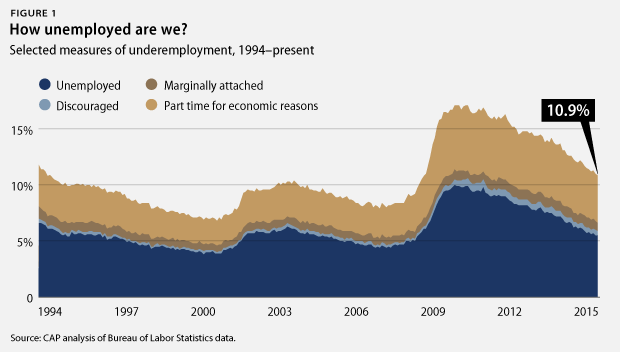

Let’s take a minute to talk about slack in the labor market. Even as the topline unemployment rate was unchanged, the broadest measure of underemployment actually fell marginally in March. This is pretty much what economics nerds have been discussing and watching for months; we are going to see a lot of people hired who aren’t showing up in the headline unemployment rate. The challenge for the Fed—and everyone watching the Fed—is that we simply don’t have much experience predicting what happens when we put the underemployed to work. There are a series of rules you can use to forecast Fed behavior in a normal world of inflation and unemployment, but those rules weren’t devised to deal with such a large share of the slack in labor markets represented by the underemployed.

Over the past year, we have seen both the official unemployment rate and the gap between the official rate and broader measures that include the underemployed come down significantly. We have also seen anemic wage growth and little evidence of inflation. In other words, we are still well below the economy’s potential. The big change over the past year has been the other headwinds the U.S. economy faces, mostly from abroad.

Global commodity prices remain low—which is great for Americans in the short-term, especially at the gas pump, but is a worrying indicator that the world economy is not operating at capacity. Big increases in supply make it harder to separate out the effects of supply and demand in oil markets, but prices for basics such as agricultural products and iron ore also point to weaker global demand. These are just a few of the reasons the U.S. dollar is appreciating, making U.S. exports less competitive and driving down demand for U.S. factory production.

In response to this softening of global demand, central banks around the world—most importantly in Europe—are starting to do what they’re supposed to do and lower rates to raise demand. But with Japan, Europe, and China all pursuing stimulus, due to weak economies, it’s tough to make the case that inflation is an imminent risk and that the Federal Reserve needs to tighten policy at this moment.

Moreover, if you are as worried about deflation as inflation, then it’s probably not the right time for the Fed to tighten policy—even more so with the gridlock in Washington pushing U.S. fiscal policy in a more contractionary direction for the foreseeable future. That being the case, this month’s weak jobs report may actually be good news for the U.S. economy in the longer term, as it underlines the downside risks we face. To those of us concerned about long-run potential gross domestic product and the short-run risk of deflation, anything that jolts the Fed into another rethink of policy is welcomed news.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center for American Progress.