Young Americans today are confronted by an unemployment crisis unlike any we have seen in recent times. To say that these Americans are having a difficult time entering today’s labor market is an understatement. As recent reports have documented, the unemployment crisis facing young Americans takes many forms, including high school students who are having a harder time finding afterschool jobs, twenty-somethings who are increasingly stuck in unpaid internships instead of paying jobs, and college graduates who are settling for low-wage, low-skill jobs such as waiting tables or serving coffee.

While each of these is evidence of the troubles facing young workers, none lays out the full scope of the nation’s youth-unemployment crisis. The reality is that youth unemployment is a much bigger problem than lawmakers have acknowledged. According to our analysis, there are more than 10 million Americans under the age of 25 who are currently unable to find full-time work—a number greater than the population of New York City, a city of about 8 million people.

As we have written before, America’s youth-unemployment crisis will have serious, enduring costs for individuals, society, businesses, and all levels of government. At 16.2 percent, the unemployment rate among Americans ages 16 to 24 is more than twice the unemployment rate for people of all ages. These young people are facing significantly higher rates of unemployment than any other age group, as Figure 1 below shows.

Some of the negative impacts of high youth unemployment are already clear: Young people are increasingly failing to make payments on their student loans, delaying saving for retirement, and moving back home with their parents. Other consequences will be felt long into the future. According to our analysis, a young person who experiences a six-month period of unemployment can expect to miss out on at least $45,000 in wages—about $23,000 for the period of unemployment and an additional $22,000 in lagging wages over the next decade due to their time spent unemployed.

Businesses will consequently suffer from reduced consumer demand, and taxpayers will feel the impact in the form of lost revenues, greater demand for more government-provided services such as health care, increased crime, and more welfare payments. There is no question that lawmakers must enact broad job-creation measures to reduce overall unemployment and get our economy back on track. But because youth unemployment is disproportionately high and its consequences especially long lasting, any such measures should emphasize getting young people back to work.

In order for lawmakers to craft policies to do so, it is important to understand the different categories of young people that make up America’s unemployed youth. A high school student in need of a part-time job is in a very different position than a college graduate stuck in an unpaid internship, and this variation in circumstances will likely require different policy approaches to get both young Americans back to work.

In this brief we analyze data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey and find that there are 10.6 million Americans under the age of 25 who are not fully employed—more people than live in the most-populated city in the country. Specifically, this brief will explore the two groups of people who make up America’s young unemployed demographic:

- 2.5 million teens ages 16 to 19 who are either out of work or underemployed

- 8.2 million young adults ages 20 to 24 who are either out of work or underemployed

Finally, this brief will explore the challenges facing young college graduates, who are experiencing high unemployment, low-quality jobs, and declining wages.

2.5 million teens are out of work or underemployed

There are 2.5 million Americans ages 16 to 19 who are out of work or underemployed. This group includes teens who are employed part time when they would rather be working full time, teens who are enrolled in school while actively seeking employment, and teens who are neither working nor enrolled in school. (see Figure 2)

Of these 2.5 million teenagers, nearly 300,000 are employed part time but are seeking full-time work. This means that they want a full-time job, but are not working full time because their employer cut back their hours or they could only find part-time work. This group is not included in the official unemployment rate, but because they are not working to the full extent that they desire, it is also an indicator of just how difficult the labor market is for teens today.

Another 728,000 teenagers are enrolled in school but are unemployed and actively seeking employment. Members of this group could include a 16-year-old high school student looking for an afterschool job at the mall, or a 19-year-old single mother who needs a full-time job during the day while attending community college at night. Unemployment is clearly a problem for the latter because she would need to provide for her family while also bolstering her education credentials, but it is also a problem for the former because afterschool jobs can play an important role in teens’ development. More than just providing teens with spending money, afterschool jobs can also help teens develop soft skills such as interacting with co-workers and time management, along with helping them explore career options.

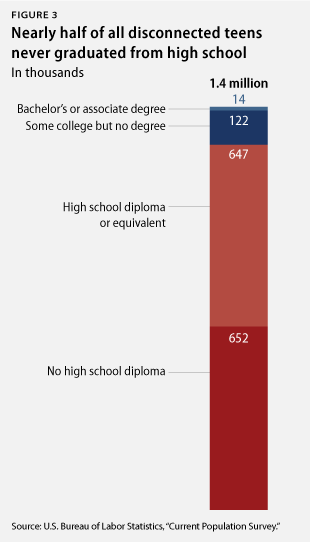

Finally, 1.4 million teens encompass a group that social scientists sometimes refer to as “disconnected,” which means they are neither enrolled in school nor working. This group is particularly worrisome because these teens are not accumulating human capital in the form of either education or work experience, the loss of which will hinder their employment opportunities, social mobility, and income in the future. Without school or work, research has demonstrated that teens are more likely to become involved in crime and to rely on public assistance and government health care.

About half of disconnected teens have dropped out of high school without making the transition to a job. Another half have completed high school but have not been able to translate their education into work or further schooling. These facts suggest that addressing unemployment among teens may require efforts to keep teens in school, as well as measures to improve the transition from high school to employment and training.

Most of America’s disconnected teens are white, but black and Latino youth are overrepresented compared to their share of the youth population. Black teens, for example, make up 15 percent of the total population of Americans ages 16 to 19, but are 20 percent of disconnected teens. The fact that young black and Latino Americans are disproportionately affected by unemployment is also reflected in the higher unemployment rates for those groups: Black and Latino teens are unemployed at rates of 36 percent and 28 percent, respectively, while white teens are unemployed at a rate of 21 percent.

8.2 million workers ages 20 to 24 are out of work or underemployed

There are 8.2 million young adults ages 20 to 24 who can’t find full-time employment, including 4.1 million who are disconnected from both work and school and another 3.6 million who are working part time when they want to work full time.

As with teens ages 16 to 19, the largest group of unemployed young adults are disconnected. This includes both those young adults who are unemployed and searching for a job, as well as those who have dropped out of the labor force, many of whom have given up their employment search even though they want a job. Again, these are 4 million young adults who are not engaged in any sort of activity to develop their human capital; they are not gaining education in school, nor are they learning skills or getting experience through work. Failure to build these skills as a young adult is likely to seriously hinder their ability to join America’s middle class in the future and contribute to the economy as productive workers and taxpayers.

The majority of these disconnected young adults do not have a college education. Nearly 1 million have not graduated from high school, while 1.9 million have a high school diploma. Another 790,000 have dropped out of college without gaining a degree, which places these young adults in a perilous financial situation if they took out student loans to pay for their education—researchers have found that borrowers who drop out of college are four times more likely than graduates to default on their student loans.

As with disconnected teens, disconnected young adults are primarily white, with black and Latino youth overrepresented relative to their shares of the youth population. Black youth make up 16 percent of Americans ages 20 to 24, but they are 23 percent of disconnected young adults. And Latino youth make up 21 percent of Americans age 20 to 24, but they are also 23 percent of disconnected young adults.

College graduates are underemployed and in debt

A college degree has long been viewed as the ticket to a good job and social mobility, but many recent college graduates are finding that their investments in education are not paying off. It is true that young people with a bachelor’s degree are more likely to find a job than their less-educated peers, but recent graduates today suffer from high unemployment rates, declining wages, lower-quality jobs, and few opportunities for advancement. At the same time, student debt in America has ballooned to more than $1 trillion, and one in four student-loan borrowers is delinquent on their loans.

In addition, unemployment rates among college graduates under the age of 30 are high relative to older college graduates. The unemployment rate for the youngest college graduates is 7.4 percent—twice the unemployment rate for college graduates in their 30s and early 40s, who experience an unemployment rate of 3.4 percent.

Moreover, the quality of the jobs available to recent college graduates today is much lower than in the past. In a new analysis, the Economic Policy Institute found that real wages for young college graduates have declined by 8.5 percent since 2000, and the share of young college graduates receiving employer-provided health insurance or pensions has also dropped in recent years.

Underemployment remains a persistent challenge for young college graduates today, as many are working jobs that don’t require a college degree. A study by the Center for College Affordability and Productivity found that half of all college graduates are working a job that the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests requires less than a four-year degree such as retail salespeople, cashiers, and restaurant servers. More than one in three are working a job that requires no more than a high school diploma, including taxi drivers and parking-lot attendants. And the authors of the study suggest that younger college graduates are more likely than older college graduates to be working a job that doesn’t require a college degree.

We have not estimated exactly how many of today’s recent college graduates are underemployed given their level of education. But it is clear that even after a young American walks across a stage to collect a diploma, he or she will not be spared the impacts of the dismal job market. And even as he or she struggles to find full-time work commensurate with that college degree, he or she faces an average student-debt burden of more than $25,000. This combination of underemployment and college debt is a dangerous one—it puts young graduates at risk of poor credit ratings, wage garnishment, and failing to save adequately for retirement. It also forces the government to spend money recovering defaulted loans, and the resulting reduced consumer demand due to lower wages and less income to spend throughout the economy can severely hold back economic recovery.

Conclusion

Four years after the official end of the Great Recession, the pace of job creation remains too slow, and too many Americans are out of work. The slow economic recovery has hit America’s youngest workers especially hard, and while the unemployment rate has fallen from its peak, more than 10 million young people under the age of 25 are not fully employed.

This brief provides policymakers with a detailed understanding of just who these young Americans are so that they can begin to develop and enact smart, targeted policy interventions to put these young Americans back to work and address the youth-unemployment crisis head on. We have long argued that policymakers must do more to create jobs and hasten the pace of our economic recovery. Our country needs broad-based job-creation measures, but targeted policies to address youth unemployment are especially crucial. Due to the severity and long-term economic costs—$20 billion in lost wages alone—of high youth unemployment, the United States can ill afford to let an entire generation of young people lose out on the earnings, wealth building, experience, and skills development that come from working.

Sarah Ayres is a Policy Analyst in the Economic Policy department at the Center for American Progress.