Fortunately for the millions of Americans who purchase health insurance coverage on their own, the nongroup market has proven resilient against the Trump administration’s numerous attempts to sabotage the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1 Enrollment has declined only modestly; insurers plan to expand their offerings again in 2021; and the ACA’s rebate program has returned billions of dollars in overcharged premiums to policyholders.

COVID-19 presents a new test for the nongroup market, which includes individual plans in the ACA marketplace as well as ACA-compliant plans sold outside it and noncompliant forms of coverage, such as short-term plans. Through new analysis of insurance companies’ rate filings for 2021, the authors find that insurers appear poised to weather the disruption and uncertainty stemming from the pandemic. Despite some experts’ concerns early in the pandemic that costs related to the coronavirus could upend insurance markets, insurers report that their 2020 expenditures are on track to be lower than in typical years due to delayed elective procedures.2 Insurers expect to increase premiums only modestly in 2021 coverage.

Given the massive job losses from the pandemic-driven economic recession, the nongroup market and the financial assistance that the ACA makes possible are playing a vital role in helping Americans stay insured amid the ongoing public health crisis. This issue brief provides an overview of the ACA marketplaces, including their enrollment levels, financial stability, and levels of insurer participation. It also describes the effects that COVID-19 could have on insurers and enrollment in the nongroup market and provides policy recommendations to strengthen the nongroup market for both consumers and insurers.

Background on the ACA marketplaces

Individuals and families who do not receive health coverage directly from their employer or through public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid may seek coverage in the nongroup, or individual, market. The ACA marketplaces provide a platform where people seeking nongroup market coverage can “shop” for comprehensive coverage that best fits their needs. Nationally, nearly 9 in 10 marketplace enrollees receive financial assistance toward their coverage.3 The ACA sought to make nongroup coverage more affordable by offering premium tax credits to consumers with household incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and cost-sharing reductions (CSR) to beneficiaries with incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of the FPL.4 Individuals can also seek nongroup coverage outside the marketplace, meaning they can purchase coverage directly from insurers or brokers that may or may not comply with the ACA’s rules, such as requirements that basic benefits are covered or bans on varying premiums by gender or health status.

The ACA marketplaces have endured numerous attempts to undermine their stability. One of the first big disruptions was Congress’ December 2014 defunding of the risk corridor program, an ACA program that was intended to smooth insurance companies’ adjustment to the new market rules.5 The risk corridor program discouraged insurers from setting premiums too high by redistributing funding from insurers that set their premiums too high to insurers that set their premiums too low6 as insurers adjusted their rates in the early years of the ACA. This past spring, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government must honor its risk corridor payment obligations.7

During the Trump administration, the individual market has faced an intense onslaught of attacks. In December 2017, after multiple legislative attempts to “repeal and replace” the ACA as a whole, Congress passed a tax bill that zeroed out the individual mandate.8 The individual mandate required all Americans to obtain health coverage or face a financial penalty, and, by encouraging healthy people to stay insured, balanced the risk pool and lowered costs.

The Trump administration has also used its executive authority to expand and promote the use of short-term, limited-duration insurance. Short-term plans, which are only loosely regulated, can discriminate against people with preexisting conditions in coverage and pricing.9 Companies that sell short-term plans often deceive consumers into believing that such plans provide comprehensive coverage at a lower cost, but these plans—often referred to as “junk plans”— frequently lack coverage for basic care such as contraception, hospital stays, and prescription drugs and can place a dollar limit on benefits.10 According to a recent report by the House Energy and Commerce Committee, enrollment in short-term plans from the nine largest U.S. insurance carriers increased by 600,000 people in 2019—the first full year in which the Trump administration’s rules expanded their availability.11 The report concludes that “these plans are simply a bad deal for consumers.”

The gravest threat to the marketplaces at present is the ongoing Texas v. California lawsuit, supported by the Trump administration, which could eliminate financial assistance for marketplace coverage and leave 23 million Americans uninsured.12 The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to hear the case this fall and issue a ruling in 2021.13 Repeal of the ACA would eliminate the financial assistance that the majority of people in the nongroup market receive and roll back vital consumer protections, such as the guarantee that plans cover essential health benefits—including mental health and prescription drugs—and the ban on discriminating against people with preexisting conditions.

Marketplace enrollment has been steady, despite sabotage

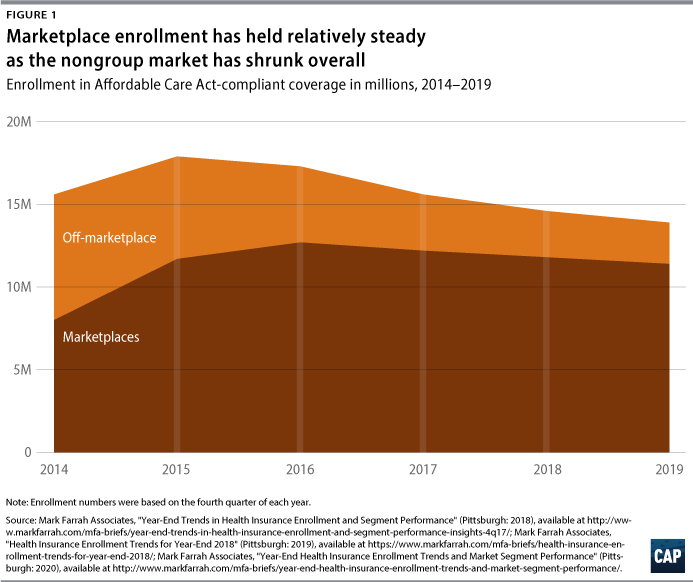

Since the ACA’s major coverage reforms went into effect in 2014, the nongroup market has grown substantially from the approximately 11 million total beneficiaries enrolled prior to the ACA.14 Although total enrollment in ACA-compliant individual plans has dropped since its peak in 2015—falling 22 percent from 17.9 million in December 2015 to 13.9 million as of December 2019—most of the shrinkage has occurred in the segment outside the ACA’s marketplaces.15 Over that same period, marketplace enrollment has decreased only modestly by around 10 percent, from 12.68 million to 11.41 million.16

Unsubsidized enrollment both outside and within the marketplace has fallen due to a number of factors, including migration to short-term plans, less outreach to the uninsured, and the zeroing out of the individual mandate penalty.17 Outside the marketplaces, enrollment in ACA-compliant individual market plans for comprehensive coverage has dropped by around 46 percent, from roughly 4.62 million people in 2016 to 2.49 million people in 2019. In addition, more than 1 million people are covered by individual plans that are not ACA-compliant, including grandfathered, pre-ACA plans and short-term plans.18 (see Figure 1)

The nongroup market is financially sustainable

Insurers’ financial performance in the individual market has improved and become less volatile over time. One useful indicator of market stability is the insurance plans’ medical loss ratios (MLRs). Starting in 2012, the ACA required individual market insurers to spend a minimum share of premium dollars on claims for medical care and quality improvement and provide rebates to the policyholders of any difference.19 In the individual market, the MLR threshold is 80 percent, meaning that insurers cannot devote an average of more than 20 percent of premium dollars to administrative costs or profits over a three-year-period.

Insurance carriers initially underestimated costs in the first couple years after the launch of the ACA’s marketplaces and market reforms as they adjusted to the new rules governing rates, benefits, and consumer protections. After paying out nearly $400 million to individual market enrollees in the first year of the program, the annual individual market MLR rebates ranged from $103 million to $238 million from 2013 to 2018.20 As insurers raised premiums in later years to catch up with higher medical claims, they eventually overshot. In 2019, the total rebates—based on plans’ loss ratios average over plan years 2016 to 2018—shot up to nearly $770 million, which was paid out to 8.9 million enrollees in the individual market.21

The rebate payments to be disbursed this year, based on claims costs from 2017 to 2019, are expected to be even greater according to the average MLR of 77 percent over the time period. Across millions of enrollees with average premiums of $600 per month, the 3 percentage point difference from the 80 percent MLR threshold amounts to approximately $2 billion to be returned to around 4.7 million individual market enrollees this year.22 In 2021 and beyond, MLR rebates could be even higher, depending on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and whether insurers receive federal funding that is past due from the ACA’s risk corridor program.23

The MLR provision has prevented insurers from capturing excessive profits through overcharging premiums, pressuring them to instead keep premiums flat or reduce them.24 Despite unexpected changes in the nongroup market’s policy environment, insurers have become more skilled over time at setting premium rates to hit the MLR target of 80 percent. Insurance plans’ loss ratios for the nongroup market during the 2019 calendar year collectively hit the mark almost exactly, at 79 percent, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.25 This is precisely what the MLR program was designed to do: hold insurers accountable and protect health insurance for consumers.

Insurance company earnings reports suggest that firms remain financially strong, and so far in 2020, deferred care has boosted companies’ profits and driven down medical loss ratios.26 For example, UnitedHealth reported that its earnings for the second quarter of 2020 were “substantially higher than anticipated” due to the pandemic.27 UnitedHealth said that deferred care contributed toward a large drop in medical care as a share of premiums—70.2 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared with 83.1 percent in the second quarter of 2019. Similarly, Cigna reported a medical care ratio of 70.5 percent due to “significantly lower medical utilization” during 2020’s second quarter, compared with 81.6 percent in the second quarter of 2019.28

Insurer participation in the nongroup market is stable

Another signal of insurance companies’ growing confidence in the nongroup market is their decision to participate in the ACA marketplaces. In the first couple of years after the marketplaces’ launch, some newcomers to the market—including most of the ACA-created Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans, known as CO-OPs—exited after a rocky start.29 However, issuer participation in the nongroup market has stabilized in recent years, and some insurers are expanding their participation. Cigna expanded its presence in 10 states this year;30 insurance giant UnitedHealthcare, which greatly reduced its marketplace footprint in 2016,31 has discussed reentering multiple states in 2021,32 including Maryland33 and Washington state34; and Oscar Health has said it will add four new states in 2021.35

Every county in the United States has been served in the ACA marketplaces by at least one insurer every year.36 The number of issuers active in the marketplaces has bounced back in the past few years, with an average of 4.5 per state this year, compared with 4.0 per state in 2019 and 3.5 per state in 2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.37 In 2020, about 88 percent of consumers in states served by the federal HealthCare.gov enrollment platform had a choice among two or more insurers, up from 80 percent the previous year.38

The effects of COVID-19 on the nongroup market

The timing of the COVID-19 pandemic poses a challenge for insurers in the nongroup market, who will need to lock in premiums for 2021 coverage amid the rapidly changing situation and major unknowns about medical spending in the near future. The first U.S. coronavirus case was confirmed in January; the Northeast was hard-hit in April; and the virus is now raging in other areas of the country.39 Meanwhile, the rate calendar for the individual market typically requires that plans calculate premium rates for the next calendar year each spring, file proposed rate changes with state and federal regulators by early summer, and finalize rates in late summer or early fall, weeks ahead of the annual open enrollment period.40

Initially, some observers expressed concern that the pandemic would overwhelm the nation’s health care system and that the surge in medical expenditures from COVID-19 testing, treatment, and patients’ long-term recovery would later cause premiums to skyrocket.41 Depending on the extent of infections in the United States, the claims costs for COVID-19 could potentially be quite large. In an “extreme” scenario—in which 60 percent of the U.S. population is infected—the costs of COVID-19 treatment could range from about 4 percent to 18 percent of baseline costs, according to estimates by the Society of Actuaries.42 A Brookings Institution research paper estimates that treatment in the 60 percent scenario would cost 9.6 percent of baseline expenditures, or $313 billion.43 Costs would be far lower under scenarios in which the virus is better contained.

The COVID-19 relief packages that Congress passed in the spring require insurers to cover testing for the virus without cost sharing.44 While these measures limit patients’ out-of-pocket costs for testing for COVID-19, they do not cap the prices that providers can charge insurers for administering these tests. In addition, many insurers have committed to waiving patient cost sharing for treatment of COVID-19.45

The pandemic has, however, suppressed other types of health care utilization.46 Many medical and dental offices temporarily shuttered or reduced their operations, and hospitals have canceled elective and other nonemergent procedures to conserve supplies of personal protective equipment and empty their beds in anticipation of admitting COVID-19 patients.47 In addition, patients have delayed or canceled their appointments in order to social distance or because of the cost.48

Preliminary information suggests that the crisis’ net effect on overall health spending will be largely a wash and could even drive a net decrease in health expenditures this year. HCA, the Nashville-based hospital chain, reported that admissions were down by 13 percent in the first half of 2020 but still posted $1.1 billion in net profit.49 A Brookings Institution analysis of health care expenditures found that “on average, COVID-19 may actually reduce insurers’ claims spending on net rather than increase it.”50

Experts predict that not all care postponed during the pandemic will ultimately occur. The Society of Actuaries has developed simulations of the effect of the pandemic on health care expenditures relative to a typical year, underpinned by these assumptions:51

Each month in which a high level of social distancing is enforced leads to an approximate 4% decline in projected annual insured health care costs relative to the baseline “No COVID” scenario. Around 40% to 60% of this decline, however, is expected to be recouped at a later date when social distancing is relaxed, allowing patients and physicians to reschedule some of the services that had previously been deferred.

Premiums in 2021

The costs of testing, treatment, and wide-scale administration once a vaccine is ultimately approved are a major source of uncertainty for insurers. Another big unknown is to what extent the elective procedures delayed in 2020 may result in a surge in 2021 or later. Yet preliminary rate filings show that insurers expect that these countervailing factors will largely cancel each other out over time. Among the 19 states that had made their initial 2021 rate filings public as of August 13, insurers attributed, on average, 0.7 percentage points of their 1.4 percent requested rate increases to COVID-19.52 This estimate is largely consistent with the findings in the Kaiser Family Foundation’s report on the effects of COVID-19 on premiums.53 The analysis found that most insurers expect the pandemic to push up premiums only modestly, with half of insurers reporting a COVID-19 impact of 1 to 4 percentage points.

A handful of carriers have requested large increases to potentially cover testing expenses.54 Among them are:

- Oscar Health, which attributes 7.4 percentage points of its requested 19.1 percent rate increase in New York to COVID-19.55 The insurer’s 2021 forecast assumes a 13 percent net increase in enrollment, “pent-up demand” equivalent to 20 percent to 70 percent of services deferred early in 2020, and ”the introduction of a vaccination in the 2021 plan year” administered to 90 percent of its members, as well as antibody testing of all its enrollees.

- Meridian Health Plan of Michigan noted a gross 8.5 percentage point increase to “reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated secondary effects,” although countervailing factors pushed its net requested increase down to 2.7 percent.56

- Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island added 2.5 percent to its requested premiums “to reflect the expected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting items such as the level of delivered services, population mix and extra costs due to the pandemic.”57

- Denver Health Medical Plan of Colorado explained, “A number of emergency regulations have been introduced in 2020 related to COVID-19…these have all been considered in the development of the 2021 rates and incorporated in the projected impact of COVID-19 of 6.4 percent.”58 The insurer is nonetheless reducing its average premiums by 4.4 percent on net.

Many carriers have not requested unusually large rate hikes or are including a disclaimer requesting the right to modify their 2021 filings later this summer based on new information. Still others did not mention COVID-19 at all in their actuarial memorandums accompanying the rate filings.59 Among those requesting little or no rate increase for 2021 are:

- The Capital District Physicians Health Plan in New York, which expects the pandemic to generate a 3.75 percent net reduction in expenditures in 2020, mirrored by a 3.75 percent increase in 2021.60 The insurer explains its belief that “over the course of this time period the net impact will be zero.” Its estimate assumes no second wave of the virus in late 2021, allowing the health care system to “return to full capacity” in 2021.

- McLaren Health Plan of Michigan says that it has “chosen not to make an adjustment to the 2021 premium rates” due to “substantial uncertainty regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on setting premium rates, including whether the pandemic will increase or decrease costs in 2021.”61

- Celtic requested that it be able to work with Tennessee’s insurance regulator to update “pricing assumptions regarding the impact of COVID-19” and resubmit rates based on new information on the science of the virus and the policy response.62

- The Maryland Insurance Administration reports that, so far, “[o]nly one of the carriers in one market elected to adjust 2021 costs due to the COVID-19 pandemic in their initial filings for any market citing uncertainty.”63 Nevertheless, “[a]ll carriers reserved the right to revisit the impact of COVID-19 as more data emerges.”

Rising unemployment is driving enrollment in the nongroup market

The economic contraction caused by the pandemic is expected to drive workers and their family members who lose job-based coverage to marketplace coverage. According to a recent report from Families USA, an estimated 5.4 million workers became uninsured due to job loss between February and May.64

Many more could lose job-based coverage as the pandemic continues. Millions of people are expected to become eligible for or enroll in marketplace plans over the coming months. A May analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that 8.4 million people who lost their jobs will be eligible for financial assistance in the marketplaces.65 Actual enrollment in the nongroup market can be expected to increase by 4.3 million this year, according to the Urban Institute’s simulation of coverage changes in an economy with 15 percent unemployment.66

Without particular changes in life circumstances, people can enroll in marketplace coverage only during the annual open enrollment period. The open enrollment period for 2020 marketplace coverage ended in December 2019 in most states and later in the winter for others. Outside of that window, special enrollment periods (SEP) are available to people with a qualifying life event, such as giving birth or adopting a child, getting married, aging off a parent’s plan, or moving. The most common qualifying event is the loss of health coverage, which could occur due to job loss, getting divorced, becoming ineligible for Medicaid, or other reasons.67

The SEP enrollment process requires that potential enrollees provide documentation of eligibility, which can be cumbersome under normal circumstances and prohibitively burdensome during the pandemic.68 In order to extend coverage to as many people as possible during the pandemic, most of the state-based marketplaces have offered SEPs with broad eligibility for the uninsured.69 These COVID-19 SEPs have resulted in at least 300,000 additional Americans enrolling since March across eight states.70 (Enrollment data were not available for the four other states with COVID-19 SEPs.)

The federal government has so far refused to create a COVID-19 SEP for the 38 states that use the HealthCare.gov enrollment platform operated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), despite calls by state officials for them to do so.71 CMS recently issued a report stating that 188,000 more people have enrolled in policies via “traditional” SEPs through HealthCare.gov this year than have in other years.72 However, a simple extrapolation of the SEP activity among the state-based exchanges marketplaces shows that HealthCare.gov would likely have enrolled an additional 440,000 to 640,000 Americans if it had offered a 60-day SEP with minimal eligibility restrictions.73

While the impact of this atypical SEP enrollment on the nongroup market’s risk pool, 2021 premiums, and net enrollment is still in question, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute report that in their discussions with insurers about the impact of COVID-19, “insurers were confident about the ability of their plans to absorb higher enrollment.”74 It is possible that SEP enrollees in 2020 could lower average risk in the nongroup pool. In Maryland and Rhode Island, more than half of individuals enrolling through the states’ COVID-19 SEPs were under the age of 35.75 By comparison, people under age 35 accounted for only one-quarter of HealthCare.gov open enrollment sign-ups.76

As people who lose their job-based coverage sign up for marketplace plans, however, others who are enrolled in the marketplaces may transfer to Medicaid instead as their incomes fall.

Policies to strengthen the nongroup market for consumers and insurers

Given the great uncertainties about 2021, policymakers should consider ways to encourage insurers to remain in the market and ensure that consumers face fair prices for coronavirus-related care. In the longer term, the nongroup market can be strengthened through administrative changes and legislation to improve the affordability and accessibility of marketplace coverage for America’s low-income and middle-class families, including those facing the loss of job-based coverage. The federal government and states should take the following steps.

Open a federal SEP during the coronavirus crisis

Given the unique circumstances of a global pandemic and widespread job loss, the federal government should offer an opportunity for Americans to enroll in health coverage outside of the open enrollment period. Like actions taken by most of the states that operate their own marketplace, the federal government should open a COVID-19 SEP with broad eligibility to allow Americans to obtain comprehensive coverage and financial assistance.77

Provide flexibility on rate filings for 2021

To maximize insurer participation, competition, and consumer choice in the marketplaces, CMS and states should provide flexibility from the traditional rate filing schedule. Insurers should be allowed to revise rates closer to open enrollment—instead of being forced to commit by mid-summer or earlier—because the spread of COVID-19, innovations in treatment, and the policy environment are all rapidly changing.

Prevent manufacturers and providers from price gouging for COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccination

No drug manufacturer, health care supplier, laboratory, or provider—including hospitals and physicians—should be allowed to gain profits due to the pandemic. While the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provide protection to many patients against out-of-pocket costs, unchecked high prices charged to insurers could come back to hurt consumers in the form of higher premiums later on. Congress should set limits on what can be charged for COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccines.78

Limit the availability of short-term health insurance and other junk plans

The Trump administration rolled back consumer protections on short-term insurance, allowing plans to be offered for up to one year and renewed indefinitely. These looser rules on duration, combined with short-term plans’ ability to deny coverage and set rates based on preexisting conditions, give insurance companies more opportunities to cherry-pick healthier people and draw them away from the comprehensive coverage risk pool. The next administration should restore the limits on short-term plans, which would not only reduce the chance that consumers mistake them for comprehensive coverage but also strengthen the ACA-compliant risk pool and lower premiums for comprehensive coverage.79

Enhance the ACA

The ACA led to a historic expansion of health insurance, yet millions of Americans still remain uninsured or underinsured. In late June, the House passed H.R. 1425, an act to enhance the Affordable Care Act.80 The Democrat-sponsored bill, which picked up a few Republican votes in the House but will not be taken up by the Senate, would bolster the nongroup market by expanding the subsidies available to low- and middle-income families and dedicating more funding for outreach to the uninsured.

Meanwhile, states that have not yet created reinsurance programs through the ACA should do so to support the nongroup market during the pandemic and beyond.81 By offsetting unusually large claims costs, reinsurance both reduces risk for participating insurers and can lower premiums for consumers.

Conclusion

The nongroup market has withstood many disruptions since the introduction of the ACA’s rating rules and marketplaces. Many of the attempts to undermine the legislation have been political; the ACA repeal lawsuit, for example, remains the biggest threat to the nongroup market. While the COVID-19 pandemic presents a new challenge to the U.S. health care system, the general stability of enrollment, insurers’ financial outlook, and insurers’ expectations for 2021 suggest that the market will remain a reliable source for comprehensive coverage for years to come.

Emily Gee is the heath economist for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. Charles Gaba is a health care analyst and the founder of and editor for ACASignups.net. Nicole Rapfogel is a research assistant for Health Policy at the Center.

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Center for American Progress.