Introduction and summary

A flurry of recent news stories highlights the scourge of tax dodging by wealthy individuals and large corporations.

Some of the stories have involved brazen criminal tax evasion on a shocking scale, including revelations that Paul Manafort, President Donald Trump’s former campaign chair, managed to hide more than $30 million of income that came from clients in Ukraine; he used a byzantine network of shell corporations and secret offshore bank accounts.1 Despite a conspicuously extravagant lifestyle, Manafort was only caught after being swept up in an investigation of Ukraine’s deposed leader.2

Other news reports chronicled sophisticated techniques used by extraordinarily wealthy people to defeat the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), including the story of Georg Schaeffler, a billionaire who allegedly used a complex series of transactions to avoid taxes on billions of dollars of income from loan cancellations. When the IRS challenged him, he litigated the agency into submission.3 There were the Wall Street banks and hedge funds that, according to U.S. Senate investigators, used financial derivatives to shelter $34 billion in investors’ profits from ordinary tax rates.4 And then there is the Trump family, which allegedly engaged in outright fraud to dodge some $500 million in taxes when transferring wealth between generations.5

Other shocking stories highlight the tactics that large, multinational corporations employ to report their profits in corporate-friendly tax havens instead of in the United States.6

These stories, which are just the tip of the iceberg, have a common thread running through them: When it comes to policing tax compliance among wealthy individuals and corporations, the IRS is badly outgunned.

As IRS researchers highlighted in a recent report, is that the United States lost an average of nearly $400 billion per year in unpaid taxes from 2011 to 2013. Moreover, over the past decade, Congress has made the problem much worse. It has given the IRS new responsibilities while sharply cutting the agency’s budget. The IRS has lost more than one-third of its enforcement personnel.

The tax system relies on voluntary compliance. The good news is that the overwhelming majority of Americans are honest and in fact view paying taxes as a civic duty and patriotic.7 But when some taxpayers cheat and get away with it, it undermines other Americans’ faith in the integrity and fairness of the system. It makes them feel like “chumps.”8 Moreover, awareness that other people are cheating can make people more likely themselves to cheat. Not only is tax evasion often linked to corruption and other crimes,9 but it also erodes confidence in U.S. institutions in general.

The bulk of revenue losses from tax noncompliance, and the broader problem of aggressive tax avoidance, is from high-income individuals and multinational corporations. These wealthy individuals and entities have opportunities to avoid taxes that are not available to ordinary workers, for whom taxes are withheld directly and automatically from every paycheck. Consequently, the weakening of tax enforcement increases inequality. It also shortchanges the federal government, draining revenue needed for critical services and investments.

This report assesses the problem of tax evasion and avoidance. It explains how the IRS lacks resources, as well as misdirects the resources it does have, and suggests ways to improve tax enforcement and ensure that policymakers can better address the issue.

The United States loses hundreds of billions of dollars each year to unpaid taxes

The most systematic effort to measure the amount of revenue that the United States loses every year in unpaid taxes is the Tax Gap report produced periodically by the National Research Program (NRP) of the IRS. The tax gap results from both intentional evasion—people cheating on their taxes—and unintentional noncompliance. The report’s estimates are based primarily on samples of tax returns selected for audit, with additional adjustments.10 The tax gap analysis is a major undertaking, with results not published until several years after the years studied. In September 2019, the IRS published its most recent estimates for the period of 2011 to 2013.

From 2011 to 2013, the United States lost $381 billion in revenue annually due to tax evasion and noncompliance

The Tax Gap report found that the United States lost an average of $381 billion in unpaid taxes annually during that period. The average annual gross tax gap—the amount of taxes that taxpayers failed to pay voluntarily and on time—was $441 billion. IRS enforcement actions and late payments brought in $60 billion per year, resulting in a net tax gap of $381 billion.

Needless to say, $381 billion is a lot of revenue for the U.S. government to forgo every year. From 2011 to 2013, it was about one-seventh of “true” total tax liability; in other words, for every $7 in taxes owed, about $1 in taxes went unpaid, even after enforcement.11

To put that in context, $381 billion was more than half of what the federal government spent annually on national defense from 2011 to 2013. It was significantly more than what the government spent to provide health care for more than 50 million Americans through Medicaid.12 And it was more than the United States spent on all mandatory income security programs—including nutrition assistance, Supplemental Security Income, unemployment compensation, family support and foster care, and refundable tax credits—combined.13

In terms of what the United States could have invested in but did not, $381 billion is about six times what it would cost to provide universally affordable quality child care in the United States.14 It is about 19 times what it would have cost to end homelessness in America, according to one estimate.15 And it is more than twice what it would cost to rebuild America’s infrastructure under House Democrats’ new plan.16

Furthermore, the tax gap is likely even larger now. If compliance rates have held constant since the 2011–2013 period, the net revenue loss in 2019 would have been $574 billion.17 And as discussed below, substantial cuts to IRS enforcement resources have also likely widened the tax gap.

The biggest portion of the tax gap is business owners underreporting their income

There are three forms of tax noncompliance: nonfiling, underreporting, and nonpayment. Underreporting is by far the biggest problem, responsible for 80 percent of the gross tax gap.

Components of the tax gap, 2011–201318

Nonfiling refers to tax returns that are not filed on time and the tax owed on those returns that is not paid on time. It equaled $39 billion in lost tax revenue.

Underreporting refers to tax returns that are filed on time but that understate the amount of tax owed. It equaled $352 billion in lost tax revenue.

Underpayment refers to taxes that are reported on returns but that are not paid on time. It equaled $50 billion in lost tax revenue.

The total gross tax gap, then, was $441 billion.

Enforced and other late payments recouped $60 billion in unpaid taxes.

The total net tax gap, then, was $381 billion.

The largest single component of the tax gap is underreporting of business income on individual tax returns, which accounts for $110 billion per year in lost revenue before enforcement. That type of income represents the profits of business entities such as partnerships, S-corporations, limited liability companies (LLCs), and sole proprietorships, which do not pay corporate income tax. Instead, their owners report their share of the businesses’ profits on their individual tax returns. In addition to the $110 billion in income tax, owners of such businesses also failed to pay in a timely manner $45 billion per year in self-employment tax.

Individuals underreported $57 billion in tax on nonbusiness income as well. Misreporting of tax credits accounted for $42 billion of the gross tax gap, and other types of income tax misreporting—such as exemptions and deductions—accounted for $36 billion in lost tax revenue.19

The corporate income tax gap before enforcement was $37 billion annually. As discussed below, however, this figure is likely an underestimate, and it does not reflect the larger problem of international corporate tax avoidance.

Virtually all wage income of workers is properly reported, but this is not the case for other forms of income

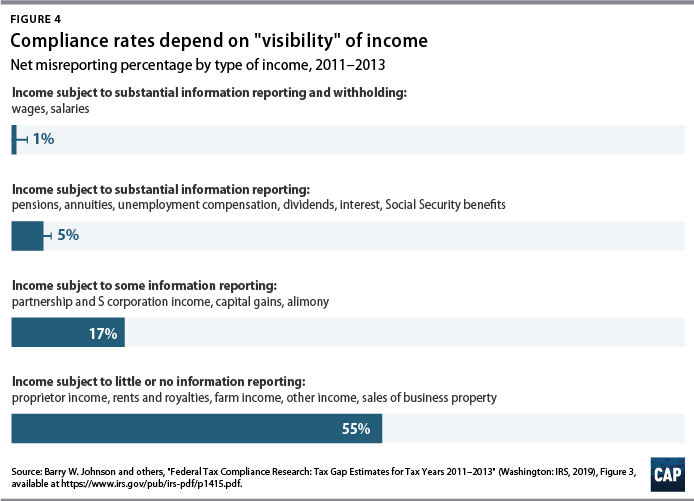

One of the most striking aspects of the Tax Gap report is the widely varying noncompliance rates for different types of income. Virtually all wage and salary income is properly reported; only 1 percent is not.20 Wages are subject to both third-party information reporting and withholding. Employers are obligated to file information returns—W-2s—with the government reflecting the amount of wages paid to each employee and provide identical copies to employees. As a result, it is next to impossible for regular workers to misreport wage income without the IRS knowing about it. Wage income is also subject to withholding, meaning that employers set aside a portion of employees’ paychecks for income and payroll taxes and remit it directly to the IRS on a quarterly basis. The IRS is said to have high “visibility” into the forms of income, such as wages, that have both third-party information reporting and withholding.

By contrast, there are much higher rates of noncompliance for forms of income into which the IRS has little visibility—usually business and capital income. Income from passthrough entities such as partnerships and S-corporations has a net misreporting percentage of 11 percent, not including payroll tax. Farm income and nonfarm business proprietor income have misreporting rates of 62 percent and 56 percent, respectively. Capital gains—received through the sale of assets such as stocks, business interests, and real estate—have a misreporting percentage of 23 percent.21

High-income taxpayers are primarily responsible for the tax gap

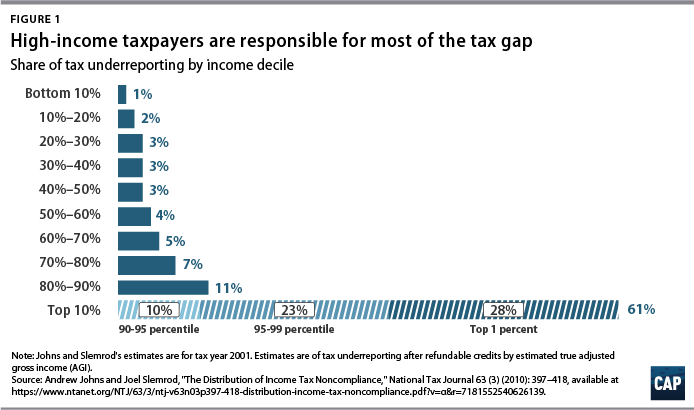

The Tax Gap report does not estimate the distribution of the tax gap—or how much tax noncompliance by low-, middle-, and high-income Americans costs the government. But researchers have derived such estimates from the IRS’ findings. In 2010, tax economists Andrew Johns and Joel Slemrod found that the highest-income 10 percent of taxpayers are responsible for 61 percent of tax underreporting.22 More recently, Lawrence Summers, a distinguished senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and former secretary of the Treasury, and Natasha Sarin, assistant professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania and finance professor at the Wharton School, estimated that the highest-income taxpayers are responsible for an even greater share of the tax gap, with the top 1 percent responsible for roughly 70 percent of underreporting.23

One of the main reasons that high-income taxpayers account for such a large share of the tax gap is that they receive more income of the types that the IRS has difficulty monitoring.24 The vast majority of low- and middle-income taxpayers’ income derives from sources that have strong third-party information reporting, such as wages and Social Security benefits. But high-income taxpayers are much more likely to receive income that requires weaker information reporting and no withholding, such as partnership income or capital gains. High-income taxpayers also have the resources to hire professionals to create sophisticated tax avoidance or evasion schemes.25

The official tax gap estimates are only part of the story

The IRS’ official tax gap estimates do not tell the entire story when it comes to tax evasion or the distinct but related issue of aggressive tax avoidance. In fact, the problem is much bigger, for at least several reasons:

- Offshore tax evasion. The IRS’ tax gap estimates omit a large share of cross-border activity.26 The tax gap theoretically includes unreported income from assets hidden offshore, but the audits that form the basis of the IRS’ tax gap estimates rarely catch that type of evasion. Though the United States has taken several important steps over the past decade to combat offshore evasion, the problem undoubtedly persists. Researchers estimate that Americans hold $1.2 trillion in offshore financial assets,27 and while it is unknown how much of this wealth is undeclared, there is much anecdotal evidence that suggests Americans are continuing to hide assets offshore. Paul Manafort, for example, hid $75 million in offshore accounts until he was caught.28

- “Legal” tax avoidance. Because the tax gap is estimated as the difference between what taxpayers pay and what they lawfully owe, the revenue losses from lawful measures taken to avoid taxes are not included. Most tax avoidance behavior is perfectly legal and even intended—for example, when an individual contributes money to an individual retirement account to lower her tax bill and get the benefit of tax deferral. But since tax law is complex and ever evolving, there are large gray areas between legal tax avoidance and illegal tax evasion. An entire industry of accountants, lawyers, and other professionals advise wealthy individuals and businesses on these gray areas. Many of the murkiest areas involve valuation of assets or services. For example, the tax code requires owners of S-corporations who run the business or work for it to pay themselves “reasonable compensation.”29 That rule is intended to ensure that these owners pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on the share of their income that derives from their labor. But they frequently lowball that number, paying themselves mostly in the form of profits that are not subject to Social Security or Medicare taxes.30 In the unlikely event that the business owner is audited, the IRS may challenge whether the compensation is in fact “reasonable” and seek to adjust it—but in practice, the IRS is especially overmatched in such fact-intensive inquiries. Since the IRS’ tax gap estimates are based on the results of audits, they exclude a great deal of aggressive tax-minimizing behavior that walks the fine line between avoidance and evasion.

- Corporate profit shifting. The biggest form of “legal” tax avoidance not included in the tax gap estimates is corporate profit shifting. Many global corporations structure their internal transactions to report as much of their profits in tax haven countries as they can get away with—and as little as possible in the United States. These corporate tax avoidance strategies are distinct from criminal tax evasion, but they exploit vast legal and factual gray areas. Corporations commonly locate intangible assets—such as copyrights or patents, which exist only on paper—in jurisdictions where they pay little or no tax on the profits generated from them.31 Economist and CAP Senior Fellow Kimberly Clausing estimates that the United States is losing about $60 billion per year from corporate profit shifting.32

- Passthrough business noncompliance and the new loophole. Passthrough businesses such as partnerships and S-corporations do not pay taxes on their profits. Instead, their profits “pass through” to their owners, who are required to report their share of the profits on their personal tax returns. But a recent study by Treasury Department and academic economists found that 30 percent of income reported on partnership tax returns—amounting to $200 billion in 2011, the year studied—cannot be unambiguously matched with the ultimate owners who should be reporting the income. “Partnership ownership is not only concentrated [among high-income earners], but also opaque,” the authors found.33 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that audits of passthrough businesses have been ineffective at locating income.34 Congress overhauled partnership audit procedures in 2015, which will hopefully improve enforcement. Unfortunately, the major federal tax legislation enacted in 2017 carved out a new 20 percent deduction for certain passthrough business income. Tax experts across the spectrum warned that creating such sharp and largely arbitrary distinctions in the treatment of income would open the door to new avoidance schemes—another gray area that will stretch the IRS’ enforcement and litigation resources.35

- Informal economy. The tax gap estimates also do not include unreported income from informal, underground, and criminal activities that is especially difficult for the IRS to detect.36

- Time lag and methodological challenges. The IRS’ latest tax gap report covers tax years 2011 to 2013, a time when IRS budget cuts were only beginning to take effect. Former IRS researcher Kim Bloomquist notes that the agency’s method in estimating the corporate tax gap fails to account for the recent “precipitous decline” in the number and thoroughness of audits of large corporations.37 In fact, the IRS’ estimates of the corporate tax gap from 2011 to 2013 are based on the results of audits from several years earlier. Fewer and lighter audits may have swelled the corporate tax gap by the time of the 2011–2013 period, and corporate audit coverage has declined even further since then. Though Congress has given the IRS some additional enforcement tools, it seems very likely that the steep decline of audit coverage and the winnowing of IRS personnel have had a negative effect on tax compliance.38

The IRS cannot adequately enforce the tax code given current resources and priorities

The magnitude of the tax gap is largely the result of policy choices. Congress has failed to give the IRS the resources and tools the agency needs to ensure better tax compliance. The IRS is auditing fewer taxpayers, with the steepest declines in audit coverage occurring for the tax returns of high-income individuals and corporations. When the IRS does examine taxpayers with substantial legal resources at their disposal, the agency is badly overmatched.

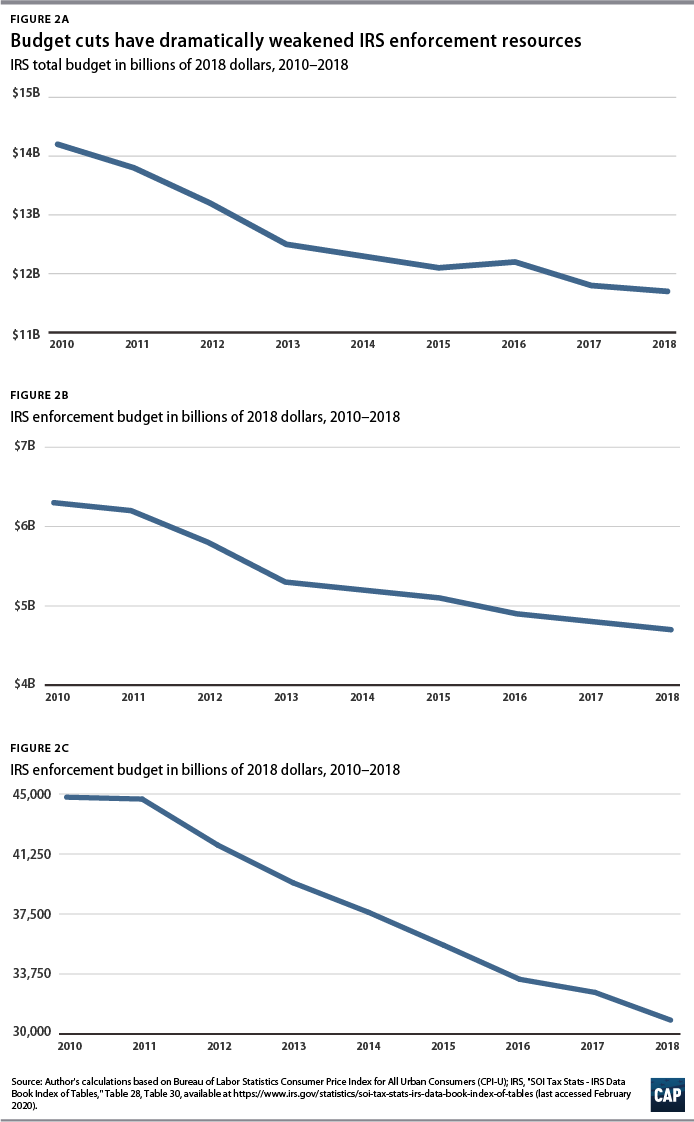

Congress made substantial cuts to the IRS’ budgets over the past decade, at a time when the agency’s responsibilities grew. IRS funding peaked in fiscal year 2010 at $14.2 billion in 2018 dollars, but by fiscal year 2018, it had been cut by 17 percent in real terms.39 Had the IRS’ budget been held constant, adjusting for inflation, the agency would have received $14 billion more in funding.40

The enforcement functions of the IRS saw the steepest cuts in funding, with examinations and collections cut by 33 percent and investigations cut by 28 percent. These cuts hit at a time when the IRS’ workforce was aging and many of its experienced personnel were retiring. From 2010 to 2018, the IRS lost 48 percent of its revenue officers, 41 percent of its tax technicians, and 35 percent of its revenue agents.41 All told, the IRS has lost about 14,000 of its enforcement employees since 2010—a drop from about 45,000 to 31,000.42

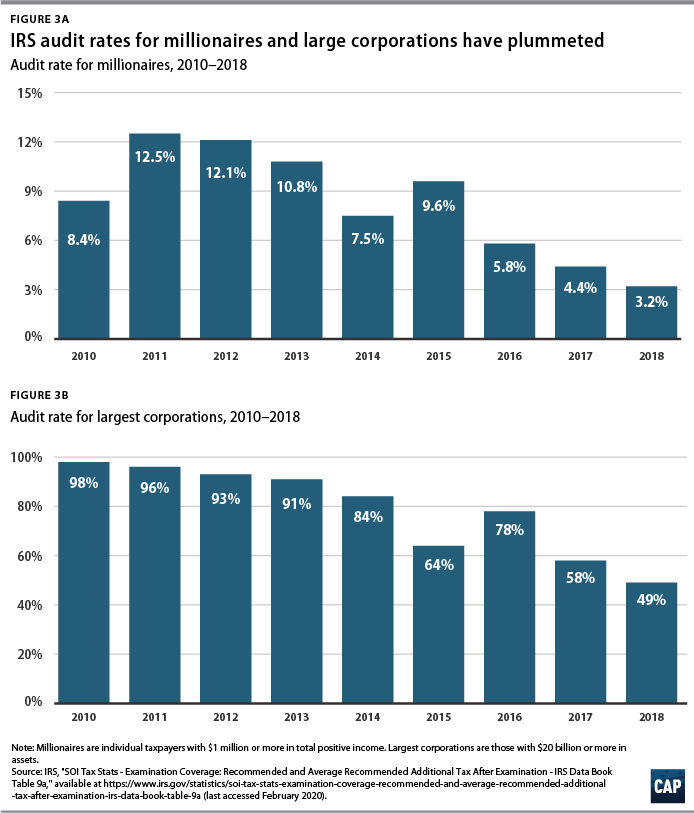

Not surprisingly, the IRS is doing less with less: Audit rates have plummeted, especially for corporations and high-income individuals. The total audit rate for individuals has dropped from 1.1 percent in 2010 to 0.6 percent in 2019.43

Audit rates for millionaires have dropped by more than half in just the past three years, to the point where 97 out of every 100 millionaires are not audited.44 A decade ago, nearly all very large corporations were audited; now, fewer than half are.45 Corporate audits brought in $12 billion less in FY 2018 than in FY 2010.46 Given resource constraints, the IRS division responsible for auditing large corporations has said it is shifting its focus from examining a corporation’s entire return to zeroing in on specific issues. And the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) reported last year that the IRS is not selecting or prioritizing issues based on past compliance results or potential impact on compliance.47 The IRS has also become more willing to compromise with corporations during audits and accept small adjustments rather than pursue cases through appeals and litigation.48

IRS budget cuts have benefited criminal tax cheats. Due to budget cuts and attrition in the ranks of special agents—the specially trained “cops” on the tax beat—the IRS is initiating fewer criminal investigations and referring fewer cases to the Department of Justice for prosecution.49 The IRS has nearly one-third fewer investigations personnel than it did a decade ago.50 In FY 2012, the IRS initiated 5,125 criminal investigations; in FY 2018, the number dropped to 2,886—a 44 percent reduction. The IRS referred 680 tax fraud cases for prosecution in 2018, down from 1,401 in 2012.51 A former IRS criminal enforcement officer told ProPublica, “Due to budget cuts, attrition and a shift in focus, there’s been a collapse in the commitment to take on tax fraud.”52

The IRS is even failing to pursue high-income people who completely fail to file tax returns. TIGTA found that the IRS has failed to pursue 369,176—or 42 percent of—high-income nonfilers in tax years 2014 to 2016, who owe a collective $16 billion. The remaining 510,239 high-income nonfilers and the $29 billion they owe are in the IRS’ collection inventory, “but generally will not be pursued due to decreased Collection resources.”53 The IRS is also sending out fewer notices to taxpayers who have information on their tax returns that does not match information the IRS has received from information returns such as W-2s and 1099s.54

Funding issues have also helped set back the IRS’ efforts to crack down on offshore tax evasion. In 2010, Congress enacted the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which imposed new requirements on foreign financial institutions in an effort to prevent them from hiding assets of their American accountholders. Pursuant to FATCA, the U.S. Treasury Department struck cooperation agreements with 113 countries. However, recent reports by government watchdogs have found that the IRS has taken few of the steps needed to implement the law.55

Though Congress has provided some modest funding increases for the IRS in the past two years,56 the agency’s problems could get worse before they get better, as the IRS may lose some of its most experienced personnel with no ready way to replace them. According to the IRS commissioner, nearly half of the IRS’ workforce is eligible to retire over the next two years, and less than 3 percent of the IRS workforce is under age 30.57

The agency’s brain drain will leave it ill-equipped to enforce the law. In particular, at current funding and personnel levels, the IRS is nowhere near capable of sufficiently tackling the complex issues that arise in the tax affairs of corporations and very wealthy individuals. In testimony to Congress earlier this year, former IRS attorney Kenneth Wood described the mismatch between large corporations and the IRS when it comes to audits of corporate transfer pricing.58 Transfer pricing is critically important for tax collection because it determines how much of the total profits of global corporations are reported in the United States and how much are reported in other countries, including tax havens. During his testimony, Wood explained:

The facts of each transaction are, typically, very complex, the economic analysis is difficult and not susceptible of precision, and the legal guidelines are somewhat blunt. In short, the task of auditing the pricing of trillions of dollars of transactions, within the statute of limitations, is an extraordinarily heavy lift. And as budgets shrink and senior personnel with substantial transfer pricing experience retire and cannot be replaced, transfer pricing audits become more and more challenging, and tax revenues fall. …

On the other side of the equation are large, well advised multinational corporations that control the facts but resist responding to legitimate IRS inquiries in a timely manner in the hope that they can run out the clock before the IRS has fully developed it’s case. Given the tax dollars at risk, these taxpayers spend tens of millions of dollars annually on tax litigation. If you are curious, I suggest you review the financial statements of taxpayers that have recently litigated, or are litigating, a large transfer pricing case. These expenditures support not just a substantive defense of their tax position but also efforts to undermine the IRS’s ability to develop it’s case. It is hardball litigation by counsel zealously representing their clients, and they have far larger budgets than the IRS. Taxpayers are understandably willing to spend millions to save billions. While the IRS has excellent, very hard working litigators, the organization has far fewer resources than taxpayers to devote to these cases.

The resources available to government auditors and litigators will never match those of very wealthy individuals or large corporations, who have white-shoe law firms, Big Four accounting firms, and other resources on their side. But in recent years, the disparity in resources has grown significantly. ProPublica recently reported on how IRS auditors struggled for years to obtain documents and piece apart the byzantine transactions that Facebook used to, in its own words, “park profits” in offshore tax havens, with the agency running into resource limitations.59 A recent study found that had the IRS’ enforcement budget been about $1 billion larger annually, it would have collected an additional $34 billion in revenue from large corporations from 2002 to 2014, reducing the estimated corporate tax gap by nearly 20 percent, in addition to additional revenue from individuals and other businesses.60

In short, by starving the IRS of the resources to do its job, the United States is transferring tax revenue to the people—primarily high-income individuals—who are evading or aggressively avoiding taxes.

IRS audit priorities are badly out of balance

While resource constraints are the IRS’ biggest challenge, the agency has also focused its resources poorly, disproportionately targeting low-income workers. The IRS’ enforcement efforts are targeted especially at tax returns claiming the earned income tax credit (EITC), a tax credit for low-income workers that supplements wages.

The EITC accounts for only a small part of the overall tax gap. In fact, misreporting of all tax credits accounted for less than 10 percent of the gross tax gap from 2011 to 2013.61 Congress has also taken several steps intended to reduce EITC and Child Tax Credit noncompliance in the past several years that were not in effect during the period analyzed in the Tax Gap report.62

In 2017, 18 percent of all individual taxpayers claimed the EITC, yet EITC claimants were 43 percent of those who were audited.63 EITC recipients are twice as likely to be audited than other taxpayers.64 As ProPublica found, because audit rates for high-income individuals have declined so rapidly in recent years, the IRS now audits EITC recipients at the same rate as the top 1 percent of taxpayers.65

The IRS’ disproportionate focus on EITC recipients is inequitable along several dimensions. The IRS currently audits people much more heavily in high-poverty areas of the country.66 The five counties with the highest audit rates are predominantly African American rural counties in the South.67 The disproportionate focus on EITC recipients in audits comes on top of special restrictions for claiming the credit that do not apply to most other tax benefits.68

The manner of EITC audits is also problematic. Most EITC audits are conducted by correspondence: The IRS sends letters to taxpayers stating that they are being audited and requesting that they substantiate their EITC claims within 30 days. Because of the lack of personal contact, correspondence audits are cheap for the IRS to conduct but very difficult for taxpayers to navigate.69 The IRS’ National Taxpayer Advocate has reported to Congress that correspondence audits are one of the agency’s “most serious problems.” The correspondence audits confuse and intimidate taxpayers, often failing to provide them sufficient time to respond or a point of contact to whom to speak.70 The vast majority of EITC recipients do not have a professional representing them, and many face language barriers.71

Researchers analyzing a sample of EITC correspondence audits found that the vast majority resulted in credits being denied due to nonresponse or insufficient response from the taxpayer, which could indicate either that the EITC claim was invalid or simply that the taxpayer was ill-equipped to respond in time. Only 15 percent of audits were able to confirm ineligibility for the credit; in 40 percent of cases where the credit claim was denied but taxpayers later received assistance from the Taxpayer Advocate Service, the IRS’ decision was reversed.72 Correspondence audits also do not improve the tax filers’ understanding of the rules going forward, and research suggests that many who are in fact eligible for the EITC are deterred from claiming it—and potentially even from working—in the years following a correspondence audit.73 The IRS’ focus is on conducting and closing the audits as quickly as possible, not on whether the audits help taxpayers understand the law better or improve their future compliance.74

In April 2019, Sen. Ron Wyden (OR), the top-ranking Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, demanded that the IRS develop a plan to reprioritize its audit resources.75 However, Internal Revenue Commissioner Charles Rettig responded by laying the blame on Congress for not providing enough funding to audit more higher-income taxpayers. According to Rettig, “The IRS cannot simply shift examination resources from single issue correspondence audits to more complex higher income audits because of employee experience and skillset.”76 The typical tax examiner conducting correspondence audits, Rettig wrote, “is not trained to conduct a high income, high wealth taxpayer audit.” In other words, given current IRS resources, the IRS can send letters to low-income taxpayers demanding additional substantiation but cannot audit more wealthy people.

Commissioner Rettig asserts that EITC correspondence audits are “the most efficient use of available IRS examination resources.” That assertion is questionable. TIGTA has noted, for example, that audits of taxpayers with incomes above $5 million produced an average of $4,545 in tax adjustments per hour of revenue agents’ time and recommended that the IRS reallocate resources to focus on high-income tax returns.

The IRS’ disproportionate focus on EITC claims raises fundamental equity concerns. One of the reasons it is so cheap for the IRS to audit EITC recipients—and why the IRS recoups so many credits when taxpayers fail to respond or respond sufficiently—is that low-income taxpayers do not have the means to hire representation to defend them in audits. While wealthy and corporate taxpayers who find themselves audited have significantly more resources than the IRS, the imbalance of resources is the extreme opposite for low-income taxpayers.

Commissioner Rettig is not wrong in emphasizing that the IRS currently lacks the resources to audit higher-income taxpayers thoroughly and effectively. But the disproportionate targeting of EITC claimants for audit, and the experience of the audits, is corrosive to overall taxpayer morale, sending the signal that the law is not being enforced fairly or evenly.

In sum, the official “tax gap” and the related problem of aggressive tax avoidance drain the U.S. government of hundreds of billions of dollars of needed revenue every year. The failures of tax enforcement increase inequality both directly—because high-income and corporate taxpayers are mainly responsible for the revenue shortfall—and indirectly—because the revenue could be invested in ways that enhance broad-based prosperity. The IRS does not have the resources to adequately enforce the tax laws, with the problem getting significantly worse over the past decade. And the IRS’ audit priorities are out of balance. Policymakers intent on addressing overall economic inequities must address how U.S. tax laws are enforced.

Strategies to improve tax enforcement

Policymakers have several ways to improve tax enforcement, including providing the IRS additional resources, better allocating those resources, and giving the IRS additional visibility into transactions.

Invest in IRS tax enforcement

Congress should make a substantial, multiyear investment in tax enforcement so that the IRS can make long-term plans to bolster its human and technological resources. After years of substantial real cuts to the IRS budget, the agency has seen a very modest funding increase. In the FY 2020 budget, the total IRS budget was increased by 1.8 percent and the enforcement budget was increased by 3.1 percent—essentially flat, given inflation and cost-of-living adjustments for federal workers.77 Much more is needed to rebuild and further strengthen the IRS’ enforcement function.

Two areas of investment are particularly important: hiring more, and more highly skilled, enforcement personnel and investing in technology.

The IRS has ground to make up in rebuilding its workforce. The agency lost opportunities to bring in younger personnel because of a hiring freeze in effect from 2011 to 2018.78 And with 45 percent of IRS personnel eligible for retirement over the next two years, the IRS faces a crisis. “Highly trained and experienced revenue agents who work the most complex audits take many years to replace,” explains GAO auditor James McTigue.79 It takes at least three years to equip new personnel to handle complex returns, such as those for business owners, according to the Tax Policy Center’s Janet Holtzblatt.80

Incremental funding increases through annual appropriations will not be enough. Congress must provide a major, multiyear funding increase to enable the IRS to rebuild its workforce. Top priority should be given to onboarding and training enforcement personnel who will be equipped to examine complex individual, corporate, partnership, and estate tax returns. Such an investment would more than pay for itself. Natasha Sarin and Lawrence Summers note that the average IRS employee makes roughly $55 per hour. And according to the IRS, revenue agents auditing multimillionaires return approximately $4,900 in tax adjustments per hour.81

Given the increasing importance of technology, many of the next generation of IRS agents will need new skills. IRS Criminal Investigation Division Chief Don Fort said, “We need agents that have cyber background; we need agents that are stronger in computer fields. We need investigative analysts that have these skills; we need data scientists.”82

In addition, Congress must invest in the IRS’ technological resources. The IRS’ information technology (IT) is notoriously antiquated. The core systems that hold taxpayer records were state of the art 60 years ago,83 but now they are the oldest in the federal government.84 Yet the IRS’ many systems are layered on top of this dinosaur technology, limiting efficiency, imposing legacy costs, and threatening to crash.85 As the IRS’ programmers retire, the agency is struggling to find new personnel who know the archaic programming language.86 The IRS’ IT systems diminish the quality of taxpayer service in numerous ways.87 Yet the IRS’ IT budget is 25 percent less in real terms than it was in 1993.88 Former Internal Revenue Commissioner Charles Rossotti notes that four of the largest U.S. banks invest nearly $10 billion in technology, on average—four times as much as the IRS spends, even though each of the banks maintains records on at most one-quarter as many individuals and businesses as the IRS does.89

Improvements in information technology can equip the IRS to better enforce the tax laws. Advanced data analytics is becoming an increasingly important component of tax enforcement, but to use those tools effectively and securely, the IRS will need modern technology.90 The IRS has implemented what it calls a Return Review Program (RRP), which uses analytics to help detect potentially fraudulent tax returns claiming refunds and to intercept those refunds before they are paid out. However, the IRS has not sought to use the RRP’s capabilities to detect potential misreporting on tax returns not claiming refunds or to help select returns for audits or other types of compliance efforts. In the view of the Government Accountability Office, by failing to apply RRP to returns not claiming refunds, the IRS may be missing opportunities to catch fraud and noncompliance more efficiently and make progress toward closing the tax gap.91

In April 2019, the IRS announced a six-year strategy to modernize its IT systems, with a total estimated cost of $2.3 billion to $2.7 billion.92 To put that amount in perspective, Rossotti notes that the four largest banks spend $3 billion to $5 billion annually on technology improvements.93 Congress, however, appropriated only $180 million for the current fiscal year for systems modernization—two-thirds of what the IRS requested—underscoring the agency’s challenge in relying on annual appropriations to make major, multiyear investments.94 The IRS will not be able to make the sustained investments needed to overhaul its IT systems without robust, multiyear funding.95

Change budget scorekeeping rules to more accurately account for better tax enforcement

One reason that the IRS has struggled to find adequate funding is that proposals to increase tax enforcement are disadvantaged in the legislative process, largely due to how they are scored. Under current practice, if Congress considers legislation to increase funding for tax enforcement, it would score as increasing deficits—even though there is abundant evidence that every additional dollar spent on tax enforcement returns at least several dollars in revenue.

This shortsighted practice stems from the “Scorekeeping Guidelines” agreed upon by the House and Senate Budget Committees, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and the Office of Management and Budget, which prevent the scorekeepers from taking into account any secondary effects of increases in funding for administering federal programs.96 As a result, the direct costs of increased IRS enforcement are reflected in budget scores, but the additional revenue that will be collected is intentionally omitted.97 Thus, investments in tax enforcement are scored as increasing deficits when in fact they do the opposite.98

Legislation that increases deficits is vulnerable to various procedural hurdles in Congress, including pay-as-you-go, or PAYGO, points of order, as well as the PAYGO law that forces spending cuts if Congress passes legislation during a year that is scored in total as increasing deficits. And as a practical matter, Congress cannot use investments in tax enforcement to offset the budgetary costs of other legislation.

However, the scorekeeping guidelines are only that: guidelines. Congress can, and should, change how the guidelines are applied in scoring investments in tax enforcement. In a related context, policymakers have recognized that investments in tax enforcement have manifold returns. Both the Obama and Trump administrations called for special adjustments to the caps on annual discretionary spending to create modest additional headroom for IRS enforcement funding.99

Second, while the CBO has provided nonscoreable estimates of the revenue feedback from additional funding for tax enforcement, those estimates likely vastly underestimate the return on investment from a more comprehensive approach to improving tax compliance. In the menu of “Budget Options” that the CBO publishes periodically, the office estimated that increasing IRS enforcement resources by $20 billion over the next 10 years would increase revenue by $55 billion, for a net return for the government of $35 billion.100 But those estimates only reflect revenue gained directly from enforcement actions such as audits. The CBO did not attempt to estimate the indirect effects—that is, “the extent to which taxpayers would respond to new enforcement initiatives by becoming more compliant with the tax code.”101 Tax enforcement actions make taxpayers more compliant themselves, and can have indirect ripple effects where other taxpayers become more compliant as well.

And yet those effects, while difficult to estimate, are very likely to be much bigger than the direct effects. The Treasury Department has estimated that the direct revenue effect of new investments in enforcement would be $6 for every $1 invested—and that the indirect effects from “deterrence” would be at least three times as large—implying a total return on investment, counting direct and indirect effects, of $24 for every $1 invested.102 IRS economist Alan Plumley has found that the indirect revenue effects of audits are 12 times as large as the direct effects.103 He finds that an additional $1 spent on audits returns $55 in indirect revenue, while every $1 spent on obtaining criminal convictions results in $16 in indirect revenue.104 Another study estimates that each new dollar invested in civil audits results in $58 in additional revenue by deterring noncompliance, and each new dollar invested in criminal investigation produces $66.105 Sarin and Summers estimate that the United States could gain more than $1 trillion in revenue from a comprehensive approach to improving tax enforcement.106

The CBO Budget Option is also very limited in that it simply seeks to estimate the effect of increased enforcement resources without complementary policies. The CBO acknowledged:

Combining an increase in funding with legislation that expanded enforcement mechanisms (such as enabling the IRS to obtain more information that could be used to verify taxpayers’ claims or imposing higher penalties) would probably be a more effective approach to significantly increase compliance and reduce the budget deficit.107

In sum, a more comprehensive approach that gives the IRS more resources and better enforcement tools would produce much greater returns on investment—especially when incorporating the difficult-to-estimate but potentially enormous indirect revenue effects.

Tax enforcement produces revenue directly and indirectly

Direct effect: Audits and other tax enforcement actions directly result in additional taxes, interest, and penalties collected by the government.

Indirect effect: Civil and criminal tax enforcement also produces revenue indirectly by inducing better compliance. There are “subsequent year effects,” where taxpayers who have been audited or otherwise been the subject of tax enforcement change their future compliance behavior.108 There are also more indirect “ripple effects,” where enforcement actions have a broader deterrent effect on the population at large.109

Reprioritize IRS enforcement resources and rebuild the ‘wealth squad’

New investments in the IRS must be directed to where the problem exists: the high-income and corporate taxpayers who are responsible for the lion’s share of revenue lost from weak enforcement. Currently, the IRS’ enforcement priorities are upside down, focusing disproportionately on EITC recipients. While providing additional, multiyear funding, Congress should require the IRS, as a first step, to develop a plan to restore audit rates for high-income and corporate taxpayers to 2011 levels. In 2011, 1 in 8 millionaires were audited, compared with about 1 in 30 in 2018. In 2011, nearly all of the largest corporations were audited, compared with less than half in 2018.110

Part of that congressional investment should be directed toward rebuilding the IRS’ “wealth squad,” so that the IRS has the experienced personnel needed to audit high-income taxpayers and the entities that they own, including passthrough businesses and trusts. The agency tried to stand up such a group several years ago, but Congress never provided the necessary resources. On the contrary, Congress began slashing the IRS’ budget soon after the wealth squad was launched.111 Lawyers for the wealthy taxpayers subjected to audits lobbied IRS leadership and Congress to ease up. As a result, the group’s audits were not nearly as comprehensive as originally envisioned. The wealth squad has since been “deemphasized organizationally” and folded into another IRS division.112 That decision should be reversed.

For years, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration has also emphasized that the IRS has spread its resources too thin when auditing high-income taxpayers. The IRS has defined “high income” as beginning at $200,000, and focused nearly half of its high-income audits on taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $399,999—despite the fact that taxpayers in that affluent group are more likely to be wage earners whose income is visible to the IRS and therefore “low risk.”113 Revenue agents auditing taxpayers with more than $5 million of income returned $4,545 of audit adjustments per hour—7.5 times more than the return on audits of the $200,000–$399,999 group. TIGTA has repeatedly called on the IRS to increase the high-income threshold, but the IRS has not done so.114

The IRS should also heed the National Taxpayer Advocate’s recommendations on correspondence audits, which include ensuring that taxpayers receive at least one personal contact and assigning a single point of contact for taxpayers.115 Making correspondence audits easier to navigate for taxpayers is likely to improve future compliance, as taxpayers come to better understand the rules governing tax provisions such as the EITC and their own filing responsibilities.

Expand the scope of information reporting and withholding

The Tax Gap report makes clear that a critical factor in the IRS’ ability to collect taxes on various forms of income is whether it has visibility into that income through third-party information reporting and withholding.

The largest area where greater information reporting is needed is payments to and between businesses. According to IRS research, “[T]he lack of reliable and comprehensive reporting and withholding for business income received by individuals is the main reason [that underreporting of business income is the largest component of the tax gap]. … Business income reported on Form 1040s is a much lower-visibility income source because it is not often subject to the same information reporting and withholding requirements that exist for salary and wage income.”116

A number of changes have been proposed to improve information reporting for business income:

- Require bank information reporting. To enhance visibility into business income, former IRS Commissioner Rossotti recently proposed requiring business owners and entities with more than a certain amount of income to designate the bank accounts that they use to receive business income. Banks, in turn, would issue information returns to the business owners and to the IRS—in much the same manner that employers report wages on W-2 forms to employees and the IRS—with a summary report of deposits received and disbursements. Taxpayers would reconcile the amounts reported by the bank with the amounts reported on their tax return. Rossotti estimates that the proposal would generate about $170 billion in revenue each year from both improved enforcement capabilities and better voluntary compliance. President George W. Bush’s tax reform commission made a similar proposal in 2005.117

- Require corporations and partnerships to file tax returns electronically. Universal use of electronic filing enables the IRS to analyze data on tax returns for potential mismatches with other information or other indicators of tax noncompliance. The GAO has recommended that all corporations and partnerships be required to file their tax returns electronically to “help IRS reduce return processing costs, select the most productive tax returns to examine, and examine fewer compliant taxpayers.”118

- Requiring contractors providing services to businesses to provide taxpayer identification numbers (TINs). The Obama administration proposed requiring that a contractor receiving more than $600 in payments in a year from a particular business provide that business with the contractor’s TIN—and if no TIN is provided, requiring the business to withhold taxes on the payments. Having the TIN allows the business making payments to file information returns reporting payments to the IRS.

- Third-party settlement organizations (TPSOs): With a traditional employer-employee relationship, the employer withholds taxes from the employee’s paychecks, files quarterly employment tax returns, and gives both the government and the employee an annual W-2 information return stating how much the employee earned in the prior year. However, major gig economy platforms characterize themselves as online payment platforms—technically, TPSOs—not as employers.119 Under Treasury Department regulations, TPSOs are not required to give payees information returns unless the payee has at least 200 transactions or $20,000 in payments on the platform; this results in a large amount of income not visible to the IRS.120 These thresholds should be lowered.

- 1099 reporting. In 2010, Congress strengthened two reporting requirements: Businesses would have been required to file Form 1099s for all payments to payees such as vendors if they exceeded $600 per year, and individuals receiving rental income—more than half of whom misreported their income, according to a GAO study—would have been required to issue 1099s for payments of $600 or more.121 Unfortunately, Congress reversed course and repealed these requirements a year later.122 Given the persistence of the tax gap for business taxpayers, Congress should reconsider those measures.

Better information reporting gives the IRS better visibility into more forms of income. It is also critical that the IRS make better use of the information it receives. In 2017, the GAO reported that the IRS does not automatically match the information return filed by partnerships and S-corporations—Form K-1—to the income information on tax returns filed by partners who are themselves partnerships or S-corporations.123 It should do so.

Improve employment tax enforcement

In some areas, the IRS is also failing to do basic due diligence and is therefore failing to collect low-hanging revenue. TIGTA reported that the IRS did not follow up on 83 percent of cases where employers reported to the Social Security Administration on W-2 forms that they had withheld tax from employees but did not fully report those withholdings on the business employment tax returns.124 These are instances where the IRS knows that tax is not being properly paid, totaling $7 billion in potentially underreported tax. In selecting which cases to work, the IRS was not prioritizing those with the biggest amounts of revenue at stake. TIGTA has also found that the IRS is failing to collect several billions of dollars by failing to use its authority to assess tax automatically against businesses that fail to file employment tax returns.125

Better regulate tax preparers and expand VITA programs

While many tax preparers are credentialed as certified public accountants (CPAs), attorneys, or enrolled agents, most are not.126 And there are currently no competency standards for paid tax preparers. Alarmingly, tax returns prepared by preparers have more errors than self-prepared returns, as well as larger adjustments when taxpayers are audited.127 In 2018, then-Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson warned Congress, “If anyone can hang out a shingle as a ‘tax return preparer’ with no minimum competency requirements or oversight, problems with return accuracy will abound.”128

Several years ago, the IRS moved to require paid tax preparers to register with the IRS and meet minimum competency standards. But federal courts ruled that the IRS lacked the statutory authority.129 Congress has considered legislation to overturn the court decision and provide the IRS with the authority to regulate paid preparers but has not yet acted.130 Congress should give the IRS this commonsense authority. And in the meantime, the IRS should use its existing authorities to take a more aggressive stance against unscrupulous preparers, including imposing penalties with more regularity.

Research also suggests that low-income taxpayers’ returns that are prepared by volunteers at Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) sites have high rates of compliance. This suggests that greater public and private funding for VITA programs would help improve tax compliance at the same time as it reduces low-income taxpayers’ reliance on costly paid services.

Improve tax gap estimates and their presentation

Integrate the tax gap into the improper payments processes

Every tax dollar that goes unpaid has the same effect on the federal Treasury as a dollar that is misspent by a government program. Yet the tax gap tends to receive less regular attention from policymakers and the media than the problem of erroneous payments by government programs, or so-called improper payments. This is despite the fact that the U.S. budget is affected far more by tax noncompliance than by improper payments. In FY 2018, agencies reported improper payment estimates totaling $151 billion, or 4.6 percent of total spending for the estimated programs—compared with the 2011–2013 net tax gap of $381 billion per year, which was 14 percent of true tax liability over that period.131

Part of the reason that improper payments receive more attention than the tax gap is that there exists a statutory regime to track and publicize them and to force federal agencies to address them. In 2002, Congress enacted the Improper Payments Information Act, requiring agencies to identify programs susceptible to improper payments and estimate the amount of such payments annually. Agencies have since been required to identify so-called high-priority programs, establish annual targets and develop plans for reducing improper payments in those programs, and improve risk assessment and other practices.132 Today, agencies report improper payments on more than 160 programs, with 20 identified as being high priority. Only one program is part of the tax code: the EITC.

Erroneous EITC refunds are counted as improper payments because they are technically government outlays. But no other kind of tax noncompliance is subject to the improper payments reporting regime, even though many kinds of noncompliance by tax filers—individual or corporate—result in improper tax refunds as well. Former Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson has said that she believes that the inclusion of the EITC within the improper payments priority list is one reason why the IRS has focused its enforcement resources disproportionately on the EITC.133

To make the improper payments framework more meaningful, Congress and the Treasury Department should strive to integrate tax revenue losses. Though it takes the National Research Program years to develop the IRS’ Tax Gap report, its estimates of the sources of unpaid taxes and noncompliance rates should be presented alongside federal agencies’ estimates of improper payments. The IRS’ NRP should provide more information about the tax gap resulting from specific types of income and specific tax provisions.134 And the Treasury Department should be required to report annually on major areas of tax noncompliance in its agency improper payments report. Areas of the tax code that have high revenue losses, such as corporate transfer pricing or income reporting of passthrough businesses, should be identified as high-priority areas that require plans to address.

Publish distribution of the tax gap

The IRS or the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis should also publish estimates of the distributional effects of tax noncompliance. Given that the IRS already estimates underreporting of various forms of income, it is feasible to estimate the amount of revenue lost by income group, as the Johns-Slemrod analysis did.135 Such distributional estimates are important in allowing Congress and the public to understand who is not paying the taxes they owe. Given that the bulk of tax noncompliance is from high-income people, having these estimates will likely increase support for better enforcement. It can only improve Congress’ decision-making.

Study the offshore tax gap

As mentioned above, the tax gap research project does not adequately seek to estimate the scope of the offshore tax gap, or the amount of revenue lost from Americans hiding assets offshore. From its very nature, offshore evasion is difficult to detect, but the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act of 2010 will continue to give the IRS more information about offshore activity.136 Congress should require the IRS to study the offshore tax gap to gauge the scale of the problem.

Conclusion

Improving the enforcement of America’s tax laws can generate much-needed federal revenue. Since high-income taxpayers are primarily responsible for the tax gap, ensuring that the wealthy pay the taxes that they owe will reduce income inequality. Curbing tax evasion and aggressive tax avoidance creates a level playing field for honest taxpayers, including regular workers who have no choice but to comply with the tax laws because taxes are withheld automatically from their paychecks and because their pay is reported on the W-2s that employers file with the government.

The final element needed to substantially improve tax enforcement in the United States is political will. Past attempts to bolster tax enforcement have fallen victim to political resistance. Congress has shortchanged the IRS’ budget, reversed its own pro-enforcement initiatives, and even pressured the IRS to ease up on audits of wealthy people.137 But there is increasing recognition that the weakening of tax enforcement is draining needed revenue—and that it is another contributing factor behind the inequality that weakens the United States’ economy and democracy. Unrigging the economy, and laying the groundwork for more inclusive prosperity, requires enforcing the tax laws fairly and adequately.

About the author

Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Sara Estep, Galen Hendricks, Divya Vijay, Curtis Nguyen, and Colin Medwick for their research assistance and input, and the many colleagues who have shared ideas and substantive feedback.