Recent news reports indicate that House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) intends to press the House of Representatives to pass what he calls a “clean” continuing resolution, ostensibly to avoid a government shutdown and to give his caucus more time to force another round of deep cuts to critical programs, services, and investments. But in fact, a continuing resolution at the levels Speaker Boehner proposed—totaling approximately $988 billion in overall discretionary funding—would already include another round of spending cuts. The speaker’s plan would have Congress endorse 100 percent of next year’s sequester spending cuts for nondefense programs and services and about 60 percent of the automatic defense spending cuts. It is easy to see why this approach would be attractive to Speaker Boehner and the Tea Party; it is much harder to understand why any progressive or centrist would support such an approach.

Of course, Congress should do everything within reason to avoid a government shutdown. A shutdown would have painful consequences for the American people and the American economy. At the same time, Congress must resist unreasonable demands to make further damaging cuts to important investments in our economic future, such as education and scientific research; basic public safety protections, such as food and drug inspections and law enforcement; or services that help support struggling families. These services, programs, and investments have already suffered from enormous cuts—and we are likely to feel the ramifications for years. Yet even more cuts are embedded within Speaker Boehner’s continuing-resolution proposal.

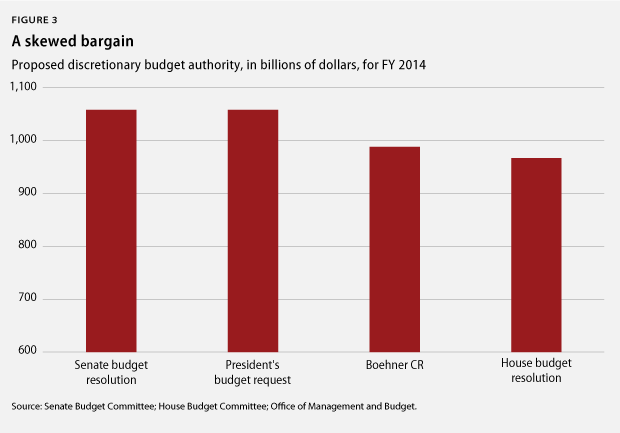

Both the Senate Budget Resolution and the president’s budget proposal reject the additional cuts that are embedded in the speaker’s plan. They both call for funding levels that are consistent with the original deal embodied by the Budget Control Act. The speaker’s proposal is $70 billion below that level, but just $11 billion above the House Budget Resolution. Members of Congress and members of the American public who oppose further cutbacks should not accept something in a stopgap measure they would surely reject in a long-term plan. Progressives and centrists should not provide support for cuts that they oppose, even if they are dressed up in the guise of a stopgap measure.

Heading for another fiscal confrontation

At the end of September, the spending authority that Congress gave the government for fiscal year 2013 will run out. At some point before that, Congress must pass new legislation that sets funding levels for FY 2014, which begins on October 1 of this year. If Congress does not pass such a measure before that date, the federal government will shut down, bringing serious consequences for the economy and the American people.

Two years ago, as part of the Budget Control Act, Democrats and Republicans actually agreed on the overall levels for the type of funding—known as discretionary funding—that must be passed each year to keep the government running. Indeed, the budget plan adopted by Senate Democrats this year adheres to those agreed-upon spending levels. If the Republican leadership in the House had done the same, there would be no risk of a government shutdown. Unfortunately, the House GOP leadership is demanding another round of damaging austerity cuts to domestic discretionary programs, such as health care services, public safety efforts, and critical investments in basic scientific research and education.

The budget blueprint adopted by the House Republican caucus calls for an additional $70 billion in cuts to nondefense discretionary accounts, amounting to a 15 percent cut from enacted 2013 levels. The magnitude of these cuts is so large that the same members of Congress who adopted that budget plan have been unable to translate it into actual, specific program cuts they can support. When the House tried to pass a bill that provided specific funding amounts for transportation and housing programs in line with their topline spending-cut target, for example, the cuts were so deep that the bill could not garner enough Republican support for it to pass, and the GOP leadership was forced to pull the bill from the floor. Even more egregiously, they have failed to even write a bill that would fund an array of health and education programs at the levels their proposed cuts would necessitate. The failure of the appropriations process this summer shows that Republicans cannot actually pass funding levels consistent with their own House budget resolution.

With the House Republican caucus unable to chart a path forward that adheres to the preposterously large spending cuts that they say they want, it appears that Speaker Boehner is trying to encourage his members to fall back on the only-slightly-less-preposterous spending cuts known as the sequester. He recently floated the idea that Congress should enact a stopgap funding measure that would continue funding at post-sequester levels from 2013—approximately $988 billion.

Why Boehner’s ‘clean’ resolution is nothing of the sort

Speaker Boehner has been trying to describe his preferred approach as a “clean” continuation of current spending levels. In fact, it is not “clean” at all; those are not the levels that Congress originally enacted for 2013 in the final consolidated appropriations bill. They are what we ended up with only after a new round of spending cuts went into effect—cuts that were designed to be so damaging that they would never be allowed to kick in. If Congress adopts those levels for next year, they will not be continuing the original levels from last year. They will be adopting all of those added cuts. Just as it would be incorrect and misleading to describe a continuation of an anomalous increase in spending—Recovery Act funding, for example—as being a simple “clean” extension of previous levels, so too is Speaker Boehner’s claim that $988 billion is a “clean” continuation of 2013 spending.

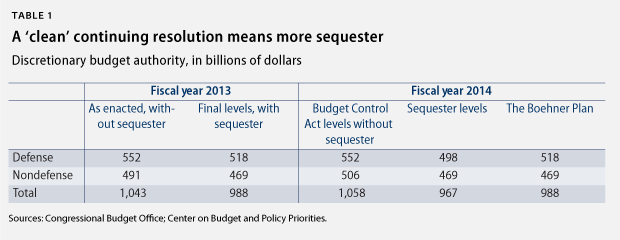

Some numbers here can help clarify matters. In March 2013, Congress finally passed a consolidated appropriations package that set funding levels for the government through the rest of FY 2013, allocating $552 billion for defense and $491 billion for nondefense, for a total of $1,043 billion. This was in line with spending limits required by the Budget Control Act. But that final appropriations bill did not repeal or adjust the sequester spending cuts. This meant that the appropriated levels were automatically reduced to $518 billion for defense and $469 billion for nondefense due to sequestration, for a final total of $988 billion. That $988 billion level is what the speaker wants to extend—not the original, enacted levels at totaling $1,043 billion.

By extending last year’s post-sequester levels, Speaker Boehner is trying to lock those additional spending cuts into place and create a new baseline from which future negotiations must begin. A comparison between the speaker’s plan and merely acceding to the automatic sequester cuts makes it clear why he is pushing his approach. Under the sequester, without any adjustment at all, nondefense funding would be set at $469 billion, and defense would end up with $498 billion. Speaker Boehner’s approach would also allocate $469 billion for nondefense, the same amount as under the sequester. For defense, the Boehner plan would allocate $518 billion, a $20 billion increase over the sequester. In other words—for nondefense programs in particular—a continuation of 2013 post-sequester levels is no different than the sequester itself. Having Congress adopt those levels in the short term is likely to make it easier for conservatives to keep those cuts in place for the long term.

Enormous cuts, the struggling economy, and a receding fiscal challenge

Needless to say, this proposal should be anathema to progressives and centrists in Congress. Policy experts from across the political spectrum have decried the deleterious effects of the sequester spending cuts. The Boehner plan would mean adopting 100 percent of the nondefense sequester cuts for another year and nearly 60 percent of the defense cuts.

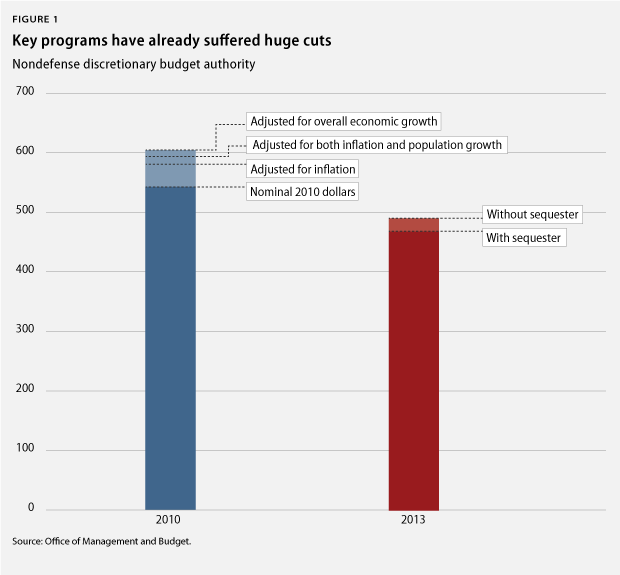

Nondefense programs have already experienced very large cuts. In 2010, funding for all nondefense discretionary accounts totaled approximately $542 billion, equivalent to about $575 billion in today’s dollars. In 2013, funding for these same programs totaled $491 billion even before accounting for sequestration, a 15 percent real reduction from just three years ago. That reduction does not include the effects of population growth or economic growth. Furthermore, over the past 10 years, total nondefense funding has averaged nearly $530 billion, after adjusting for inflation. That puts the pre-sequester 2013 allocation about 7 percent below the average from the past decade.

These spending cuts have not been kind to the U.S. economy. The contraction in federal government consumption and investment has caused a direct drag on economic growth in eight of the past 10 quarters, including the past three quarters consecutively. Although down from its peak several years ago, the unemployment rate remains greater than the level most forecasters had predicted three years ago, when Congress began cutting federal spending. And for many American families, the recession is not over. Indeed, median household income today is lower than it was when the Great Recession technically came to a close in June 2009.

It is in this economic context that conservatives in Congress are demanding even more cutbacks. The Congressional Budget Office has reported that implementing the sequester cuts in 2014 will reduce real gross domestic product, or GDP, by 0.7 percent and reduce employment by 900,000 jobs. Since Speaker Boehner’s approach would cement most of these cuts into place, the immediate negative economic consequences alone should be enough for Congress to reject it.

Adding to the absurdity of considering further cuts is the simple fact that the allegedly worrisome federal fiscal situation—the stated rationale for these cuts—is not nearly as worrisome today as it once was. Measured as a share of GDP, this year’s federal budget deficit is expected to come in at its lowest level since 2008. More importantly, the projections of future budgets have improved dramatically over the past three years. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio was once expected to rise to unprecedented levels by the end of the decade; it is now expected to decline for the next five years and only then rising slowly, to end in 2023 at the same level it is today.

Part of the reason for the improvement in the future fiscal picture is that Congress has already cut a lot of spending. Not only are current funding levels for nondefense discretionary programs significantly below those of 2010, but overall discretionary spending is slated to hit its lowest level on record, measured as a share of GDP, by 2017. And that is without sequestration. If Speaker Boehner’s plan goes forward and Congress ends up adopting those levels for the year, it would mean even more cuts to vital programs, services, and investments.

The practical effects of the Boehner approach

In practice, these spending-cut numbers mean that that we are seriously underinvesting in key areas such as scientific research and education. Consider the National Institutes of Health, or NIH. In 2010, Congress allocated about $31 billion in funding for NIH. If that funding had merely kept pace with inflation, funding for NIH in 2014 would be about $33.5 billion. But if Congress continues the 2013 levels after the sequester, then NIH will get only about $29 billion, a 13 percent cut. That is equivalent to about 20,000 fewer grants for medical research. The story is similar for K-12 education. In 2010, funding for grants and other programs run out of the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education was equivalent to about $24.5 billion in 2014 dollars. The Boehner approach would set funding about 15 percent lower, a cut of about $3.7 billion, enough to pay for about 70,000 elementary school teachers.

It’s not just investments in our future that have suffered from these cuts. Basic public safety protections have absorbed massive reductions as well. Three years ago, Congress provided about $1.5 billion in state and local grants to help with law enforcement. The Boehner plan would provide about one-third less, a cut equal to about 9,000 police officers. Under the Boehner plan, the Food and Drug Administration would get about 10 percent less than it did three years ago, an amount large enough to fund the implementation of a transformative food-safety plan to focus on preventing foodborne illness, which causes 128,000 hospitalizations, 3,000 deaths, and economic losses of $78 billion per year. Funding for the Coast Guard would be down 9 percent from 2010 levels, a reduction equivalent to 18 Fast Response Cutters. Again, note that none of these cuts take population growth or economic growth into account; they only account for basic inflation.

The Boehner approach favors defense over nondefense

If Speaker Boehner’s proposed solution becomes law for the entire year, nondefense programs would be no better off than they would be under the sequester. Defense, however, would receive a $20 billion boost over sequester levels. In other words, the Boehner approach would keep the sequester in place for nondefense programs but would somewhat alleviate the cuts to defense.

Of course, the sequester spending cuts for both defense and nondefense are shortsighted and damaging. Both should be repealed or replaced with smarter approaches to deficit reduction. But to ameliorate one and not the other would be unfair and unwise. The sequester was specifically designed to be painful in the hope that Congress would seek out better ways to improve the fiscal outlook—and painful it has been. By seeking to adjust the defense sequester, Speaker Boehner is admitting that the government cannot operate under those levels. The same admission must be made for nondefense.

President Barack Obama and congressional Democratic leadership have been clear that the defense sequester and the nondefense sequester are tied together, that both should be fixed, and that one cannot be fixed without fixing the other. If Congress ends up accepting the Boehner approach for the entirety of 2014, it would be an abandonment of that pledge.

Conclusion: A poor ‘compromise’

Clearly, progressives and centrists in Congress should be extremely wary of adopting any plan that makes it easier for a minority of extremely conservative members of Congress to enact ever-more damaging cuts to vital public services or economic investments. Speaker Boehner’s plan to keep the government open is only a stopgap measure, which is not necessarily the same thing as a full year’s funding level. But over the past three years, stopgap measures have had a way of becoming the ceiling—not the floor—for each year’s final funding levels. In the three fiscal years since January 2011, there have been nine different short-term funding measures. In those three years, the final, full year’s level never exceeded the short-term levels. This is a pattern we cannot afford to repeat if Congress accepts the speaker’s levels for a short time.

But no one should mistake the speaker’s plan for anything other than an attempt to shift the ground in his favor. Consider that the House’s original proposal for discretionary funding was $967 billion for FY 2014. The Senate’s proposal is $1,058 billion, the same as the president’s preferred levels and the original Budget Control Act levels. If Congress accepts Speaker Boehner’s “compromise,” it will be setting the temporary level just $11 billion above the original House proposal but $70 billion below the Senate Democratic leadership and the president’s shared proposal. That hardly seems like a fair compromise.

Eighteen years ago, President Bill Clinton said, “America can never accept under pressure what it would not accept in free and open debate,” when he too was confronted with repeated and unreasonable demands for enormous cuts to programs he considered critical to America’s well-being. If today’s conservatives believe that what we need now is even less investment in economic growth, fewer resources for public safety, and more cuts to support struggling middle- and low-income families, then let them make that case to the country in free and open debate. They should not be allowed to pave that path with confusing number games and misleading claims about last year’s funding levels.

Neera Tanden is the President of the Center for American Progress. Michael Linden is the Managing Director for Economic Policy at the Center.