Introduction and summary

One of the many painful lessons of the 2007–2008 financial crash was that financial institutions outside of the traditional banking system could pose a devastating risk to financial stability. The failure or near failure of nonbank financial companies, including insurance company American International Group (AIG), investment bank Lehman Brothers, and finance company General Electric (GE) Capital, severely aggravated the crisis. Lehman Brothers’ catastrophic bankruptcy in September 2008 was one of the darkest moments of the crisis. The very next day, a teetering AIG was bailed out by taxpayers. These so-called shadow banks engaged in fragile bank-like activities and posed bank-like risks but faced significantly lighter regulatory safeguards than banks—which themselves were drastically underregulated. The crisis clearly and unequivocally showed that “too big to fail” was not only a banking problem but something that also applied to the failure of large, complex, and interconnected shadow banks. Policymakers could no longer doubt that the collapse of systemic nonbank financial companies could threaten the stability of the financial system and tear at the fabric of the economy.

Moreover, financial regulators with differing, and in some cases, overlapping jurisdictions were too siloed and as a consequence did not adequately communicate with one another. They instead focused on their respective pieces of the financial sector and were blind to risks that developed across jurisdictions or outside of any one regulator’s jurisdiction. No regulator or regulatory body was given the mandate to identify and address risks to the financial system as a whole. Some financial regulators did not, and still do not, even consider financial stability—in other words, promoting the normal functioning of the financial system to serve the economy—to be part of their mission.

A financial crisis is particularly dangerous because its impact extends beyond the financial system to harm the broader economy and, in particular, everyday Americans. Households, workers, and savers paid the price for this flawed regulatory regime. Unemployment shot up to 10 percent, 10 million homes were lost to foreclosure, and nearly $20 trillion in household wealth disappeared.1 The real wealth of the average middle-class family shrank from 2007 to 2010, decreasing by nearly $100,000, or 52 percent.2 The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimates that the financial crisis cost every American $70,000 in lost lifetime income.3 While topline economic indicators have recovered in the intervening years, the scars of the crisis remain and are seared into the memories of every American who lost a home, a job, or savings in the crash. And many families are not close to fully recovering economically.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 sought to address the many shortcomings in financial regulation, including some but not all of the gaps in shadow banking regulation and systemic risk oversight.4 The bill brought the derivatives markets out of the shadows, created new registration requirements for hedge funds and private equity firms, established a federal office to monitor the insurance industry and to negotiate international insurance agreements, created executive compensation restrictions for financial firms, and granted regulators the authority to wind down systemically important nonbanks in an orderly fashion—just to name a few. The central shadow bank and systemic-risk-related element of the bill, however, brought the disparate financial regulators together in a new body—the Financial Stability Oversight Council (referred to in this report as “FSOC” or “council”)—which was designed to monitor and address risks to the financial system wherever they may arise. The FSOC has several clear statutory responsibilities and tools, including the powerful authority to subject a systemically risky shadow bank to consolidated supervision and enhanced regulatory safeguards.5 During the Obama administration, FSOC Chairman Tim Geithner and his successor Jack Lew used the council’s mandate and authorities to improve communication among regulators, analyze emerging financial stability threats and vulnerabilities, and meaningfully strengthen the resilience of the financial system. The FSOC was used, as intended, to limit the chances of another devastating financial crisis.

The Trump administration, in contrast, has rejected the FSOC’s mission and has worked to undermine its authorities in several ways. As a result, the financial system is more vulnerable to risk in the nonbank financial sector.

The FSOC was structured around a tacit view that regulators committed to the council’s mission would always be in place. The experience over the past two years of deregulation under Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has blown a hole through that conception. Congress should respond in kind by revitalizing the FSOC and strengthening the regulation of the shadow banking sector. It is not enough to simply undo Secretary Mnuchin’s misguided deregulation. The FSOC’s central tools have an embedded bias against stringent regulation of systemic shadow banks and have proven vulnerable to conservative judges who are intent on defanging regulatory authorities in favor of business interests. The council’s authorities should be reoriented toward protecting the economy from financial sector risks—and away from protecting the financial sector from prudent regulation. Moreover, the FSOC should be granted new authorities to tackle systemic risk in all of its forms. Essentially, the council’s design and authorities should be crafted to withstand a future deregulatory administration. If policymakers want to mitigate the economic boom, financial deregulation, and bust cycle, the FSOC has to be resilient to the political tides that drive financial deregulation.6

This report starts by outlining the lax oversight of nonbank financial companies and the systemic-risk regulatory gaps that existed before the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Next, the report charts the development of the FSOC after the crisis, its role and actions during the Obama administration, and the Trump administration’s efforts to erode the council. Finally, the report offers several paradigm-shifting proposals that would help prevent shadow banks from triggering another crisis.

Briefly, the proposals detailed in this report include:

Bolstering the FSOC’s shadow bank designation authority: Shadow banks that meet specific quantitative thresholds should be automatically subjected to enhanced supervision and regulation, tailored to their respective risk profiles. The FSOC should have the authority to de-designate firms on an individual basis if the council determines, after conducting a rigorous data-driven analysis, that material distress at the firm and the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, and/or mix of the activities at the firm would not threaten financial stability in a period of broader stress in the financial system. The public, however, should be granted legal standing to contest such de-designations.

Granting the FSOC authority over systemically risky activities: The FSOC should have direct rulemaking authority to regulate systemically risky activities across the financial sector. An activity’s primary regulator should supervise the implementation and ongoing compliance of the rules promulgated by the FSOC. If no one regulator has jurisdiction over the activity, the FSOC should determine the appropriate regulator to fulfill that supervisory role. The council should also have the authority to complete congressionally mandated rulemakings for which the primary regulator or regulators missed the deadline prescribed in statute.

Enhancing the FSOC’s institutional capacity: The council and the Office of Financial Research (OFR) should be given minimum staffing and budget floors. The floors should double the council’s budget and staffing and increase the OFR’s budget and staffing by about 50 percent, relative to Obama administration levels. The FSOC chair and OFR director should have discretion to set budget and staffing levels above such floors. The OFR director should no longer be required to consult with the treasury secretary on the agency’s budget and should be given additional authority to acquire and share regulatory data from and between FSOC members.

Increasing the FSOC’s transparency: The council should be required to release transcripts of its meetings on a five-year time delay. The FSOC should be required to hold a public meeting and a press conference at least once per quarter. All voting members of the council should have to testify before Congress together annually on financial stability efforts, and they should have to either certify that their respective agencies are taking all reasonable steps to ensure financial stability and to mitigate systemic risk or detail the additional steps their agencies should take to do so.

Policies that would redesign the alphabet soup of financial regulators are important and worth advancing, but the perennial question of how best to streamline the current landscape of agencies falls outside the scope of this report. Given the immense institutional forces that work against reorganizing the array of agencies, beyond just the typical industry and political forces that oppose stronger regulation, it is crucial to also pursue policies that drastically improve the financial regulatory framework while building on the rails of the current architecture. The proposals outlined in this report would do just that for the regulation and supervision of the shadow banking sector.

While these proposals would substantially improve the safety and soundness of the financial system, it is worth stating clearly that targeting shadow banking risks alone is not enough. Congress and regulators must pursue policies that increase the stringency of regulations and restrictions on systemically important banks as well.7 Tighter banking regulations would both mitigate the ongoing risks posed by the core banking sector and further address the risks posed by the shadow banking sector, as the banking and shadow banking systems are deeply connected.

Improving the resiliency of the financial system and lowering the chances of another financial crisis through strong financial regulation is a pro-growth policy: It promotes long-term, sustainable economic growth. Workers, families, and savers would all benefit from tighter safeguards on the most systemically important financial institutions in this country.

Shadow banks and the financial crisis

Before the financial crisis, the dominant view among policymakers and academics was that only traditional commercial banks8 could pose systemic risk.9 Banking is an inherently fragile enterprise.10 Issuing liquid short-term liabilities—deposits—and investing in longer-term illiquid assets—loans—is tenuous.11 Banks are also highly leveraged, meaning they utilize substantial levels of borrowing to fund their assets, leaving only a small cushion of equity to absorb potential losses.12 This highly leveraged business model of liquidity and maturity transformation is prone to creditor runs and fire-sale dynamics.13 If short-term creditors pull their funds or refuse to roll over existing short-term debt, the bank must resort to selling its illiquid assets at fire-sale prices to generate cash quickly. The asset fire sales may erode the firm’s equity capital levels, increasing the incentive for more creditors to run as the firm is driven toward failure. These dynamics make banking a vulnerable business.

The failure of a bank directly affects the communities it serves. Bank failures lead to a reduction in the credit supply to businesses and households, which in turn depresses consumer spending and business investment.14 This disruption directly harms businesses, consumers, workers, and the economy.15 When a bank is large, complex, and deeply interconnected with the broader financial system, failure can be catastrophic not just for a local community but also for the entire U.S. economy.16 The fragile nature of the banking business model and its importance to the performance of the real economy necessitates the federal government’s role in ensuring the stability of the financial system. Taxpayers, through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), insure a share of bank deposits to limit the chances of depositor runs, and the Federal Reserve’s discount window provides solvent banks with emergency liquidity when needed.17 Accordingly, banks are more tightly regulated and supervised than typical commercial enterprises. Indeed, “free market” thinkers from Adam Smith to Milton Friedman recognized the need to regulate the banking sector to address its fragility and the dire consequences of bank failures on the economy. Banks face capital requirements, liquidity rules, risk-management requirements, supervision, and other rules to mitigate the chance of failure. Before the financial crisis, regulations on big banks were far too light. But there was at least an understanding that a bank could be systemically important, and a framework, albeit drastically underwhelming, was in place to mitigate such risks and deal with the failure of a commercial bank quickly to minimize economic harms.18

Nonbank financial companies can perform economic functions that are similar to those of traditional banks. They can provide credit to businesses and households, offer payment services, and manage risk. They also, at times, pose bank-like risks as well. Shadow banks may issue short-term money-like claims and engage in the type of maturity and liquidity transformation that makes banking so fragile. They may also employ substantial leverage, engage in complex financial activities, and be highly interconnected with the broader financial system. Before the financial crisis, however, the same type of regulatory scrutiny and safeguards that applied to banks were not in place for nonbank financial companies such as investment banks, insurance companies, finance companies, asset management firms, and hedge funds. Oversight of these shadow banks focused primarily on consumer, investor, and policyholder protection—not financial stability.19 Disclosure, registration, and fiduciary requirements were the central regulatory tools applied to such firms.20 The lighter regulatory touch for nonbank financial firms was usually appropriate. The reasons differ by the specific type of nonbank, but generally speaking, policymakers assumed that the business models of nonbank financial firms were less vulnerable relative to banking, that the failure of such firms could pose less risk to the economy, and that the firms largely do not rely on explicit public support such as deposit insurance.

While these factors may hold true for many financial intermediaries, the crisis clearly showed that nonbank financial firms and activities can pose severe risks to the financial system and broader economy. Even though shadow banks had not caused wider stability issues before the crisis, there were some warning signs that policymakers should have taken more seriously. For example, the 1998 failure of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), a highly leveraged hedge fund, necessitated a private bailout orchestrated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to avoid destabilizing the financial system.21 Despite this warning sign, the shadow banking sector remained severely underregulated in the lead-up to the crisis.

Shadow banks helped spark the 2007–2008 crisis by originating subprime mortgages, packaging them into mortgage-backed securities, and distributing them throughout the financial system. They also exacerbated the crisis when creditors ran from the shadow banking sector, similar to old-fashioned depositor runs. The combination of size; interconnectedness with other financial firms; complexity of operations or assets; reliance on short-term funding and susceptibility to bank-like runs; leverage; and other factors made firms such as Lehman Brothers and AIG systemically important.22 In essence, “too big to fail” is not just a problem limited to traditional commercial banks. It is a problem with very large and complex financial institutions that pose systemic risks regardless of their specific corporate charter. The cases of AIG and Lehman Brothers are instructive.

The collapse of AIG

From 2000 to 2007, American International Group more than tripled in size, from $300 billion to more than $1 trillion in assets.23 The international insurance conglomerate operated in more than 130 countries on the eve of the financial crisis and increasingly engaged in capital markets activities that were not central to the plain vanilla business of insurance.24 AIG, like all insurance companies, was primarily regulated at the state level. State insurance regulators did not have adequate resources, expertise, authorities, and incentives to oversee a global financial conglomerate.25 AIG’s holding company was lightly regulated at the federal level by the highly captured, and now-defunct, Office of Thrift Supervision.26

AIG Financial Products (AIGFP), a London subsidiary, was heavily engaged in writing credit default swaps (CDS)—a type of over-the-counter derivative that provided purchasers protection against a security’s default—on subprime mortgage-backed securities.27 This activity superficially resembled writing insurance but did not face the regulatory framework that came with writing bona fide insurance policies because AIGFP was not licensed as an insurance company, nor were the CDS treated as insurance policies for regulatory purposes. Moreover, the risks for insuring mortgage-backed securities were fundamentally more complex than the risks covered by traditional insurance. AIG’s activity both fed and fell victim to extreme risk-taking in complex financial markets. These credit default swaps enabled holders of mortgage-backed securities to hedge their risks and provided speculators a synthetic instrument to bet against the mortgage-backed securities. If the underlying mortgages remained healthy, AIG earned profits on the premiums it received for writing the CDS. Yet when the subprime mortgage market started to deteriorate, so too did AIG’s financial position. The company was required to start paying out on its CDS and as the housing market continued to worsen, AIG had to post additional collateral and margin against the declining value of the CDS positions.28 This dynamic resembled a run on the institution as counterparties demanded more liquid assets, which further strained AIG’s finances because it only had so much cash on hand to meet these margin calls.

Moreover, AIG suffered substantial losses from its securities lending business.29 AIG lent out the securities it held on its balance sheet in exchange for cash collateral from the borrower of the security. Instead of investing this cash collateral in safe, short-term assets such as Treasury securities, AIG invested it in supposedly safe—but actually illiquid and highly risky—mortgage-backed securities and other high-risk assets. When the security borrower returned the security, AIG had to return the cash collateral. Because the collateral was tied up in illiquid mortgage-backed securities that had lost value when the housing market collapsed, AIG took on losses and had to resort to fire sales to generate the cash. The securities borrowers often had the right to return the security to AIG and receive their cash at their own discretion.30 So as AIG’s financial position deteriorated, more securities borrowers closed out their positions—again creating a bank-like run on the company. And no regulator was looking at these correlated risks.

It was clear at the beginning of September 2008 that AIG was going to fail and that its failure would transmit stress to its counterparties—other systemically important institutions—and throughout global financial markets. AIG was too big, interconnected, and complex to fail. On September 16, 2008, the Federal Reserve stepped in and provided the initial support that would end up constituting the largest bailout in U.S. history—$182 billion in taxpayer assistance.31 This case shows clearly that an underregulated shadow bank can threaten financial stability. AIG carefully structured its activities to fall within the gaps between regulatory silos.32 The result: extreme risk-taking involving financial products and activities that could join together the worst elements of a banking, real estate, and capital markets crisis.33

Lehman Brothers’ failure

A day before the AIG bailout, Lehman Brothers—a $600 billion investment bank—filed for bankruptcy.34 Lehman’s catastrophic failure sparked a full-fledged run on the global financial system.35 Lehman’s business model and risk profile had distinct similarities to a traditional commercial bank, but it did not face the supervisory and regulatory framework that applied to such firms. Despite Lehman’s size, leverage, complexity, and interconnectedness—and the harm its failure could cause to the system—it was only lightly supervised by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) through a weak voluntary program.36 No regulator had the explicit authority or mandate to regulate investment banking holding companies.

The SEC, which regulated broker-dealers—a subsidiary of investment banking conglomerates—established a voluntary program for consolidated supervision and regulation of investment bank holding companies. The investment banking giants such as Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Goldman Sachs could opt in and opt out at their discretion. And those firms that did opt in faced wholly inadequate supervision and prudential regulatory safeguards. As SEC Chairman Chris Cox stated in 2008 when announcing the end of this regulatory framework, “The last six months have made it abundantly clear that voluntary regulation does not work.”37 He went on to argue, “The fact that investment bank holding companies could withdraw from this voluntary supervision at their discretion diminished the perceived mandate of the CSE [Consolidated Supervised Entities] program, and weakened its effectiveness.”38 As with AIG, Lehman Brothers carefully designed its activities to fall within the gaps between effective regulatory regimes.

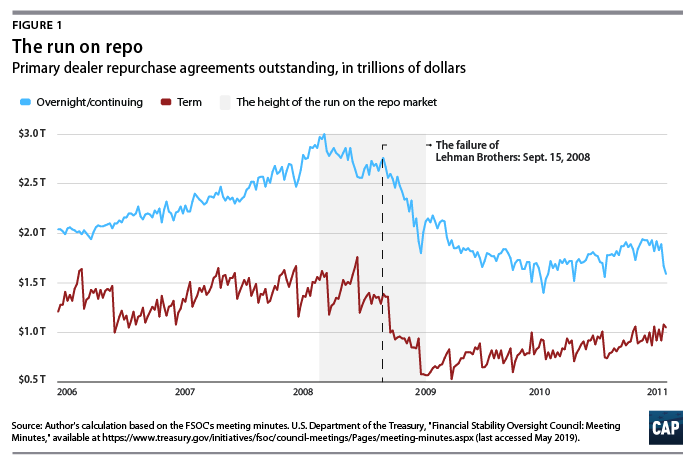

Lehman engaged in the type of leveraged maturity and liquidity transformation that makes banking such a fragile endeavor. The company funded long-term and illiquid positions in subprime mortgage-backed securities and commercial real estate investments with highly runnable short-term debt.39 Much of this trading activity was proprietary, as Lehman traders placed outsize bets on the mortgage-backed securities and commercial real estate markets.40 Before its collapse, Lehman relied on about $200 billion in overnight repurchase agreements—short-term collateralized loans—to fund its balance sheet.41 These repo transactions represented about one-third of Lehman’s overall funding, which left the firm in an extremely vulnerable position.

By 2007, Lehman was leveraged 30-to-1, meaning it had about $3 of loss-absorbing equity for every $100 of assets.42 The other $97 in assets were funded by debt. As the subprime housing market collapsed, Lehman’s assets lost value and creditors pulled their money from the firm by refusing to roll over short-term funding transactions.43 Lehman was forced to sell off its illiquid assets at fire-sale prices to generate the cash needed to meet creditor demands. The company also faced liquidity pressures from its derivatives counterparties, who demanded increased margin and collateral. Lehman was highly interconnected with the broader financial system, in part due to its extensive derivatives operations. The firm held a staggering 900,000 derivatives positions across the globe.44 The collapse in the value of its housing-related assets and the liquidity strain from the creditor run created a vicious cycle that drove Lehman into bankruptcy. Unlike the FDIC’s special authority to take over and wind down an insured bank in an orderly manner, no regulator had such authority for shadow bank failures.

Lehman’s bankruptcy filing set off a chain reaction of distress throughout the financial system. As Lehman spiraled, creditors looked at other investment banks with similar business models and fled—even if those institutions did not have significant direct exposure to Lehman Brothers. Experiencing similar duress, Merrill Lynch sold itself to Bank of America.45 Both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became bank holding companies, in part to assure creditors that they would be better regulated and better supervised.46

Another shadow bank, the Reserve Primary Fund, a money market mutual fund that invested in Lehman’s commercial paper—another type of short-term debt instrument—had to write down the value of those assets after Lehman declared bankruptcy.47 Money market mutual funds (MMMFs), which invest in short-term instruments and allow investors to redeem shares in the fund on short notice, successfully lobbied the SEC for the right to report a stable value for their shares at $1. This allowed funds to market their offerings as having the same safety and liquidity as an FDIC-insured bank account, albeit without the actual insurance or the accompanying regulatory framework.48 For that reason, investors treated these funds like a risk-free checking account that returned higher interest than an actual checking account. Assets held by MMMFs grew rapidly, from roughly $180 billion in 1983 to about $3.6 trillion the week before Lehman Brothers failed.49 These accounts were certainly not risk free, and after Lehman’s bankruptcy, the Reserve Primary Fund had to report share values of less than $1—referred to as “breaking the buck.”50 The MMMF industry had invested substantially in the commercial paper issued by other major financial firms, so Lehman’s failure and the distress at the Reserve Primary Fund sparked a run on the money market fund industry broadly.51 Because of its sheer size and the broad number of individuals and businesses that had deposited their money in these funds assuming them to be very safe and highly liquid, the federal government later decided to guarantee the entire money market fund industry.52

The activities of, and risk-taking by, Lehman Brothers thus had enormous ripple effects on other shadow banking markets and on the entire economy.

Other shadow banking risks

In addition to insurance companies and investment banks, other types of shadow banks and shadow banking activities—including finance companies such as GE Capital,53 investment funds such as MMMFs and corporate bond funds,54 securitization vehicles,55 and other off-balance sheet structures—contributed to the buildup of systemic risk outside of the traditional commercial banking sector.56 Nonbanks, including mortgage lenders, investment banks, and the investment vehicles they created, were at the heart of the securitization machine that originated and distributed the risk of subprime mortgage-backed securities throughout the global financial system.57 The same fundamental maturity and liquidity transformation, often leveraged, that makes banking inherently fragile was at the heart of most of these activities that emerged outside of the core banking system—but without the supervision, regulation, and public protections applied to commercial banks.

Moreover, research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco demonstrates that hedge funds were a key transmitter of stress throughout the financial system during the crisis.58 Hedge funds are interconnected with other systemically important financial institutions, and the data show that stress at hedge funds can have meaningful spillovers to other financial institutions.59 For example, Wall Street investment banks provide prime brokerage services to hedge funds, including direct lending.60 One need look no further than the 1998 failure of the large and highly leveraged hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management for proof that a hedge fund can pose systemic risk. LTCM had $4 billion in net assets under management (AUM) but was highly leveraged. That $4 billion in net AUM was leveraged into $125 billion in gross assets, and its derivatives activities meant that LTCM’s total financial exposures were much higher than that.61 When the firm’s bets went south, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York had to step in and facilitate a private bailout. If LTCM had been allowed to fail, it would have transmitted stress to its creditors and counterparties, who were primarily other systemically important financial institutions.

It is also worth mentioning that just because a specific firm, subsector, or activity did not trigger or exacerbate the last financial crisis does not mean that it could not threaten financial stability in the next crisis. The financial sector is constantly evolving, and while crises tend to rhyme with one another, they never look exactly the same. Regulators should be vigilant to old risks and emerging ones alike. The fact that a type of financial firm or product did not play a role in the last crisis should never be wielded as proof positive that it will not in the future.

The 2007–2008 financial crisis made it all too clear that distress at systemically important shadow banks and risky shadow banking activities could destabilize the financial system and cause substantial harm to the real economy.

No financial stability regulator

Part of the reason that shadow banking firms, activities, and certain products were not adequately regulated before the crisis was the lack of a financial stability regulator.62 The disparate financial regulators were siloed and focused on the risks and firms that fell within their respective jurisdictions. No one regulator or group of regulators had a mandate to look out at risks across the financial system that may have cut across jurisdictions or fallen outside of regulators’ purview altogether.63 Even if regulators had been equipped with the mandate to identify risks across the system, they clearly lacked the tools necessary to subject risky activities and institutions to enhanced safeguards and oversight. Shadow banking entities understood this landscape and structured their legal statuses and activities to fall within and exploit the gaps between regulatory silos. There is little reason to think their incentives have changed.

The U.S. financial regulatory framework and toolbox were not designed to mitigate threats to financial stability that emerged outside of the core banking system. The collapse of systemic nonbank financial companies and risky activities, such as the $500 trillion market for over-the-counter derivatives and the $4 trillion-plus repo market, were left in the shadows. Massive institutions and markets were opaque and drastically underregulated. The lack of regulation left the financial system fragile and, in turn, the real economy vulnerable. The shadow banking system helped trigger the crisis and deepened its impact. Filling these regulatory gaps was an important aim of financial reform efforts in the wake of the crisis.

Dodd-Frank and the Obama FSOC

In the wake of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, addressing the risks posed by shadow banks and targeting the buildup of systemic risk outside of the traditional banking sector was a top priority. Even George W. Bush’s Treasury Department understood this vulnerability and the need to act. In its 2008 “Blueprint for a Modernized Financial Regulatory Structure,” Henry Paulson’s Treasury Department outlined the need for a market stability regulator.64 The body envisioned by the blueprint would “focus on the stability of the overall financial sector in an effort to limit spillover effects to the overall economy.”65 The Group of Thirty, which included current and former policymakers, business executives, and academics, released a report in 2009 that provided financial-stability-focused recommendations for financial reform. The Group of Thirty report recommended that countries address gaps in regulatory oversight and subject certain risky shadow banks to consolidated supervision.66 As financial reform efforts heated up in the United States following the election of President Barack Obama, his Treasury Department outlined its key principles and recommendations in a 2009 white paper.67 The white paper included the creation of “a Financial Services Oversight Council,” which would identify risks to financial stability, facilitate interagency communication, and give the council tools to mitigate such risks to financial stability—including the ability to subject shadow banks to strong regulatory safeguards.

The FSOC’s mission and tools

The council envisioned by President Obama’s Treasury Department served as the jumping-off point for the creation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. The establishment of the FSOC was one of the centerpieces of Dodd-Frank and the most important action taken to respond to the risks posed by the shadow banking sector.68 Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) remarked at a Senate hearing on the council, “It was so important to address this problem [of underregulated shadow banks] that the authors of Dodd-Frank created FSOC in Title I of the bill.”69 The FSOC’s statutory mission is to identify and address threats to financial stability and to promote market discipline by eliminating market expectations that taxpayers would again bail out financial institutions.70

Lawmakers armed the FSOC with important tools to fulfill this mission. The authority to designate a nonbank financial firm as a systemically important financial institution (SIFI) and subject it to enhanced supervision and regulation by the Fed is the council’s primary tool to mitigate threats to financial stability.71 The council may designate firms if “material distress at the U.S. nonbank financial company, or the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or mix of the activities of the U.S. nonbank financial company, could threaten financial stability.”72 Designated firms face consolidated oversight, heightened capital and liquidity requirements, annual stress testing, living wills requirements, enterprisewide risk management rules, and other enhanced standards. It is important to note, however, that the Fed must tailor these rules to the business models and specific risk profiles of the designated firms. A systemically important insurance company such as AIG could pose different financial stability risks than a finance company such as GE Capital, and enhanced regulatory safeguards should reflect those differences. Relatedly, the FSOC has a separate authority to designate financial market utilities, which are engaged in clearing and settlement activities, as systemically important.73 These firms are vital contributors to the basic transactional plumbing of the financial system. Designated financial market utilities are subjected to stronger oversight and risk management rules.74 Additionally, legislators gave the FSOC the power to restrict a systemically important bank’s or a designated nonbank financial company’s activities, limit its growth, and even break it up if it poses a grave threat to financial stability.75 In terms of activities-focused authorities, the council can issue nonbinding recommendations to the regulator with jurisdiction over a given activity—if such a regulator exists.76 The FSOC also has the authority to issue nonbinding recommendations when two or more council members have a jurisdictional dispute.77

Enhanced prudential standards

When a shadow bank is designated as a systemically important financial institution by the FSOC, it is subjected to stronger consolidated federal oversight by the Fed and enhanced financial stability rules. The heightened regulations aim to limit the chances and impact of a shadow bank’s failure. These rules include:

- Capital requirements that increase the shadow bank’s capacity to absorb losses and limit the chances of failure

- Liquidity rules that make sure the shadow bank has the resources to quickly meet creditor and counterparty cash demands under stress

- Living wills that require the shadow bank to plan for its orderly failure, which creates incentives for the firm to simplify its structures and operations78

- Stress tests to annually evaluate the shadow bank’s balance sheet health during a simulated financial shock and economic downturn

- Risk management rules that require the shadow bank to prudently manage a broad array of risks across the firm

- Counterparty credit limits that prevent the shadow bank from having too much exposure to individual counterparties

Designated shadow banks are also subjected to additional financial stability safeguards, including the Volcker Rule, which places quantitative limits on proprietary trading conducted by designated firms.79 While some of these requirements, such as living wills, have universal qualities that should apply similarly to banks and shadow banks alike, many of the requirements should be tailored to the business model and risk profile of the shadow banks. The Fed is required to adapt the enhanced prudential standards accordingly and has already taken clear steps to do so.80

The FSOC was formed, in part, to facilitate better communication between the disparate regulators and has important convening authority.81 Its membership was set at 10 voting members and five nonvoting members. The voting members of the council consist of the treasury secretary, as chair; the heads of the eight federal financial regulators;82 and an additional independent member with insurance expertise. The nonvoting members include the heads of the Federal Insurance Office, the Office of Financial Research, and three state financial regulators. Dodd-Frank housed the FSOC in the Treasury Department and provided it and the OFR—an agency designed to be an independent data-driven research organization for the council and Congress83—an independent funding source outside of the congressional appropriations process. Both the FSOC and the OFR are funded through fees levied on bank and nonbank SIFIs, and both the chair of the council84 and the OFR director have discretion regarding their respective budget and staffing levels.

The creation of the FSOC was a direct response to the devastation that underregulated shadow banks, and their risky financial activities outside of the commercial banking sector, wrought on the real economy during the financial crisis. The Obama administration worked to build up the institution from scratch and used its various authorities to strive toward achieving the council’s lofty goal: promoting a more resilient financial system.

Designing an analytical framework for systemic risk

One of the first orders of business for the council was establishing its analytical framework and administrative process for using the SIFI designation authority. It identified three primary transmission channels through which stress at a nonbank financial company could have knock-on effects and destabilize the financial system.85

The first channel focuses on exposure to the firm. If a shadow bank were to fail, it would place losses on its creditors, bondholders, investors, and derivatives counterparties, and it could generally disrupt other financial firms that have exposure to the failing shadow bank. The second channel deals with asset liquidation dynamics. If a shadow bank has to offload assets in a fire sale—to quickly meet cash demands from creditors and counterparties or to otherwise reduce its leverage—it could push down asset prices and disrupt trading in those markets. These dynamics could cause losses at other financial firms with similar assets, increase funding costs for firms that rely on particular funding markets, and undermine confidence in certain financial markets. The final transmission channel zeros in on critical services or functions performed by a shadow bank. If a shadow bank that played a vital role in the functioning of certain financial markets failed, and no other firm could easily step in to take over the service or function, then such a failure could destabilize the financial system.

In addition to the three systemic risk transmission channels, the FSOC’s analytical framework factors in the extent to which the nonbank is already regulated. It also considers how the challenges in resolving the nonbank could exacerbate the financial stability risks it poses. Dodd-Frank outlines a series of factors for the council to consider when making a SIFI designation, including the firm’s leverage, off-balance-sheet activity, interconnectedness, short-term funding reliance, and others, which are embedded within the transmission channel analytical framework. For example, firms with high leverage have substantial debt counterparties that could face losses through the exposure channel. Moreover, firms with significant short-term funding are more vulnerable to the risk of runs—which could propagate risk through the asset liquidation channel.

Establishing the shadow bank designation process

The FSOC developed a three-stage process for designating SIFIs in 2012, after soliciting public feedback on the process three times.86 The first stage is designed to narrow down the vast universe of nonbanks based on certain quantitative thresholds. A nonbank financial firm that has at least $50 billion in assets and meets one of five additional metrics87—$30 billion in gross notional credit default swaps; $3.5 billion in derivatives liabilities; $20 billion in total debt outstanding; a 15-to-1 leverage ratio; and a 10 percent short-term debt ratio—advances to the second stage of the designation process. In the second stage, the council uses publicly available information and data already collected by regulators to analyze further the potential risks posed by the firm. Furthermore, the council consults with the firm’s primary regulator during this stage. The FSOC may advance firms into the third stage for an in-depth evaluation of the firm’s potential financial stability risks using the transmission channel analytical framework. At this point, the council notifies the firm that it has been advanced to the third stage of the designation process. The council acquires substantial information directly from the firm in this part of the review, and the firm may submit additional materials it believes the council should consider. After this stage of the review, the FSOC may vote to issue a “Proposed Determination” that the firm meets at least one of the two statutory standards for a SIFI designation. The firm receives the written analysis for the decision and may elect to participate in a nonpublic hearing to contest the Proposed Determination. After the hearing, the council may vote to make the Proposed Determination final by a two-thirds vote, and with an affirmative vote of the FSOC chair. If the designation is finalized, the firm will be subject to enhanced oversight and regulation by the Federal Reserve. This designation is reviewed annually to evaluate whether any designated shadow banks have sufficiently de-risked and no longer require the SIFI label. In 2015, the council also adopted a supplemental set of procedures for its designation process after considering feedback from stakeholders.88 The supplemental procedures formalized and increased the council’s engagement with companies being reviewed in the designation process and provided companies with earlier opportunities to provide input to the FSOC.89

Using the designation authority

The FSOC used this crucial tool—designation authority—four times under the Obama administration. The council found that distress at three insurance companies—AIG,90 MetLife,91 and Prudential92—and one finance company, GE Capital,93 could threaten U.S. financial stability. These institutions were designated as SIFIs and were then subjected to enhanced oversight and stronger regulatory safeguards.94 Subjecting these firms, which collectively had more than $2 trillion in assets, to more stringent consolidated oversight and regulation increased the safety and stability of the financial system. The council’s actions also demonstrated that a SIFI designation is not, with apologies to the Eagles, a “Hotel California” that guests cannot leave, as some critics have charged. In 2016, the FSOC rescinded GE Capital’s SIFI label after the firm took concrete steps to break itself up and reduce its systemic risk profile.95 Additionally, the council exercised its separate financial market utility designation authority to subject eight market utilities to enhanced risk management standards.96

MetLife lawsuit

MetLife, one of the designated insurance companies, successfully challenged the FSOC’s decision in court.97 This case demonstrated that the design of the council’s statutory designation authority was susceptible to activist conservative judges. In the suit, MetLife argued that the decision was “arbitrary and capricious” because the council used “unprecedented doomsday scenarios”; that the council did not conduct a cost-benefit analysis; and that the council did not evaluate whether the company was likely to experience distress, among other arguments.98 The council argued that it conducted a careful designation process pursuant to the discretion afforded to it by statute. In 2016, the district court judge presiding over the case, a George W. Bush appointee, agreed with several of MetLife’s arguments and overturned the SIFI designation.99

The judge’s decision added restrictions and requirements to the designation process that were not included in the statute and ran counter to the explicit discretion afforded the council by Dodd-Frank. For example, the judge faulted the FSOC for failing to conduct a cost-benefit analysis—a requirement not included in Dodd-Frank. Not including a cost-benefit analysis requirement in statute was hardly unprecedented. Certain financial regulators, including the Federal Reserve, are not required to adhere to cost-benefit analysis restrictions in their rulemakings. To support this element of the decision, the judge cited other regulations promulgated in accordance with different statutes, but those statutes explicitly required a cost-benefit analysis. The FSOC appealed the decision, and its position was supported by more than 20 of the nation’s top administrative law and financial regulatory professors,100 former government officials such as Ben Bernanke and Paul Volcker,101 and members of Congress102 who had written and voted for the statute. The Trump administration dropped the appeal in 2018, so the decision remains in force and MetLife is no longer a SIFI.103

This type of judicial vulnerability will only get more acute as President Donald Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell continue to stack the judiciary with conservative judges who want to limit the regulatory authority of executive agencies, even when it contradicts statute and the clear expressed will of Congress.

Systemic risk inquiries

In addition to exercising its authorities over systemically important institutions, the council explored potential financial stability risks posed by activities, products, and entities in different sectors of the financial system. The council is, however, highly limited in the actions and tools at its disposal to address systemically risky activities. The FSOC can only study activities and use soft power to push regulators and Congress to mitigate the risks posed by those activities. The FSOC’s primary statutory activities-based authority is to issue a nonbinding recommendation to the activity’s primary regulator, if one exists. The primary regulator is free to disregard the FSOC’s recommendations.104

The council’s power to use suasion is limited but can yield some minor positive results. Money market mutual fund activities were a significant source of systemic risk during the financial crisis.105 They were major lenders in short-term funding markets, including the commercial paper and repo markets.106 When investors pulled their funds, MMMFs in turn had to sell off assets and retreated from those markets. Their retreat negatively affected other financial institutions, such as investment banks, that relied heavily on those short-term funding markets.107 In 2010, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted limited reforms to MMMFs that clearly did not address the core underlying risks posed by these funds.108 The FSOC studied the issue and called for further action in its 2011 and 2012 annual reports.109 The SEC continued to drag its feet on the issue, so the council initiated the process for using its statutory authority to issue a recommendation to a primary regulator. In November 2012, the FSOC issued a proposed recommendation to the SEC to take further steps to mitigate the risks posed by MMMFs.110 There is also evidence to suggest that the council threatened to use its designation authority on MMMFs if the SEC refused to act.111 Before the council finalized the recommendation, the SEC promulgated new rules to better address the identified structural vulnerabilities posed by this activity.112 While the SEC’s reforms could have been significantly stronger, this is one example of the council’s soft-power tools making some impact. The action taken, however, was strictly at the discretion of the SEC, and the FSOC had no additional activities-focused mechanisms to mitigate the risk of MMMFs if the SEC simply refused to act.

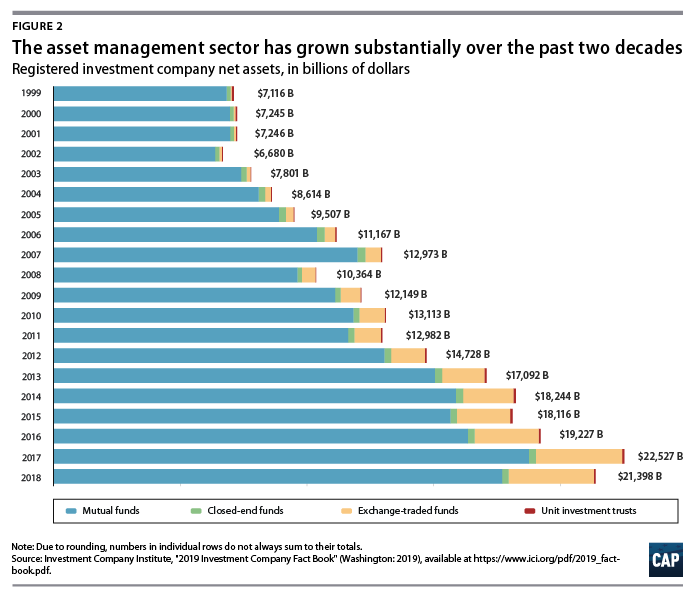

Moreover, the FSOC opened an inquiry into the asset management sector broadly in 2014. The asset management industry is an important and growing sector of the financial system. The net assets of registered investment companies in the United States—including mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, closed-end funds, and unit investment trusts—totaled more than $21 trillion at the end of 2018.113 For context, that’s roughly the same size as the entire U.S. banking system.114 Both hedge funds and private equity funds face significantly lighter regulatory standards than registered investment companies.115 They hold $7.9 trillion and $2.8 trillion in gross assets, respectively.116

The council held a public conference117 on the potential financial stability risks posed by asset management firms, funds, activities, and practices; issued a request for information to the public on asset management risks;118 discussed the topic at regular council meetings; and provided the public with regular updates on its findings.119 Throughout the process, the council repeatedly consulted with industry stakeholders, regulatory agencies, academics, public interest organizations, and the broader public.120

Through this in-depth examination, the council found evidence that some aspects of the asset management industry could pose risks to financial stability.121 In particular, the FSOC found that liquidity transformation at open-end funds—such as mutual funds—may be a financial stability vulnerability in times of broader stress in the financial system. Open-end funds provide investors with daily redemption rights but may invest in less-liquid assets such as corporate bonds. If investors run, the fund may have trouble quickly selling the illiquid assets to generate cash for redemptions. This fire-sale dynamic could lead to losses for investors—increasing the likelihood that other investors run for the door—and could push down asset prices across the asset class. This dynamic would affect other financial institutions that hold similar assets and that rely on certain funding markets. The FSOC further identified the first-mover advantage, the benefit an investor has by heading for the door first and redeeming shares before the fund has to offload the illiquid assets, as a potential accelerant for this fire-sale dynamic. This same dynamic lies behind the classic model of a bank run.122 Since the crisis, the SEC has taken some steps to mitigate liquidity risks at mutual funds, but the reforms likely do not sufficiently address these risks.123

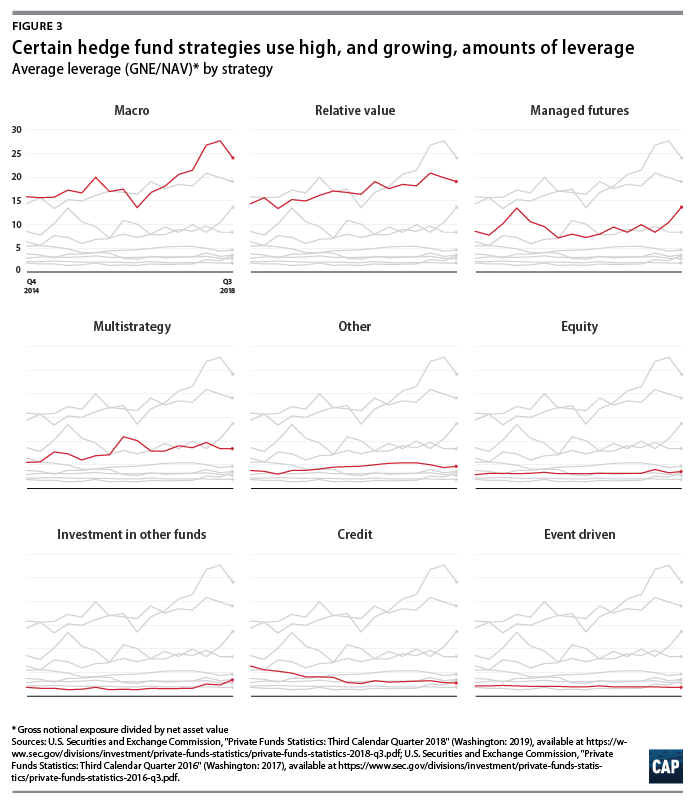

Moreover, the council identified leverage as another source of risk within the asset management sector. Funds that employ leverage—through borrowing or derivatives contracts—could transmit stress to their creditors and counterparties in the case of failure. Leverage necessarily increases a fund’s interconnection to the broader financial system. Funds that borrow through short-term funding markets could be forced to sell illiquid assets at fire-sale prices if the short-term creditors refuse to roll over funding rapidly during a period of stress in the financial system. Similarly, derivatives counterparties may demand more and increasingly liquid collateral. This could push down asset prices and place losses on financial firms with similar assets. The council focused on hedge funds in particular for this vulnerability. Hedge funds are not subject to the leverage restrictions that govern mutual funds and other registered investment funds.124 The largest hedge funds tend to employ the most leverage, and the leverage at large hedge funds is a clear financial stability concern.125 The two hedge fund strategies that use the most leverage are macro and relative value funds, which currently have a combined $1.6 trillion in financial exposures.126 The asset-weighted average leverage at funds using these two strategies is 23.8 times and 19 times respectively.127 The FSOC went so far as to create a separate hedge fund working group to continue investigating leverage in the hedge fund subsector and solve some outstanding data concerns that inhibited a complete analysis of potential risks.128

In addition, the council examined operational risks stemming from industry reliance on a small set of third-party service providers, the potential risks of securities lending in the asset management industry, and whether the failure and resolution of an asset manager could exacerbate the potential financial stability risks associated with liquidity transformation and leverage.129 The asset management industry pushed back vigorously, using its political muscle to refute the FSOC’s findings and fight the notion that asset managers should be targets for SIFI designations.130

The asset management work shows the council’s ability to conduct thorough and accountable examinations of the potential financial stability risks posed by segments of the financial system. The FSOC voted unanimously to publish a set of policy recommendations—outside of the council’s official Section 120 authority under Dodd-Frank—that would help mitigate certain financial stability risks in the asset management sector.131 But the SEC, the primary regulator of the asset management industry, has failed to follow through and implement most of the policy recommendations.

Real-time oversight and interagency communication

During the Obama administration, the FSOC also used its convening power to conduct immediate financial stability oversight in response to financial sector stress and material market developments. The council held emergency meetings at least nine times to discuss developing issues, including market volatility,132 the collapse of a financial firm,133 international market developments,134 natural disasters,135 the federal debt limit,136 and Brexit.137 In addition to the increased principal-level engagement and collaboration fostered by the FSOC, the Obama administration established several staff-level FSOC committees that ensured that the respective staffs of the council’s member agencies were in constant communication on market developments, ongoing rulemakings, and other matters.138

In Dodd-Frank, policymakers created the FSOC to address the vulnerabilities in the financial regulatory framework that were laid bare during the 2007–2008 crisis. As it stood, no regulator was tasked with the mandate and tools necessary to mitigate systemic risk—especially outside of the traditional banking system. Large, complex, and interconnected shadow banks were left severely underregulated, and highly risky activities and practices were out of sight for regulators. These activities played a central role in triggering the crisis, and the collapses of AIG, Lehman Brothers, and other shadow banks exacerbated it—bringing the U.S. economy to the brink of collapse. The Obama administration built up the council, used its tools to create a more stable financial system, and was accountable to policymakers and the public. The creation of the council was an important step toward regulating systemic risk, but some cracks in the design and extent of its tools and authorities started to emerge. The Trump administration’s tenure at the helm of the council and willful rejection of the council’s mission has made these structural vulnerabilities all too clear.

Trump’s dismantling of the FSOC

In stark contrast to the Obama administration’s efforts over the council’s first six years, the Trump administration has fundamentally rejected the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s vital mission. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Trump-appointed financial regulators have undone previous actions taken by the council, rolled back its authorities, and worked to erode its capabilities. As a result, the U.S. economy is more exposed to risks in the shadow banking sector today than it was two years ago. These actions demonstrate the political and judicial fragility of the council’s capabilities and tools, weaknesses addressed by the policy proposals discussed at the end of this report.

Deregulating shadow banks

Secretary Mnuchin’s top priority after taking charge of the FSOC in 2017 was rescinding the designations of the three remaining nonbank systemically important financial institutions—effectively deregulating these firms. In September 2017, nine years to the month after receiving the first installment of what would become the largest bailout in U.S. history, AIG’s nonbank SIFI designation was rescinded.139 Removing enhanced safeguards from AIG, a $500 billion global insurance conglomerate, was deeply misguided.140 The failure or near failure of AIG in a period of broader stress in the financial system could threaten financial stability. The same was true in 2013 when it was designated, and the firm only made modest changes to its systemic risk profile in the years following the designation.141 It still has substantial liabilities that could be redeemed at little to no penalty during a crisis. The firm’s liquid assets on hand are a small fraction of these potential runnable liabilities, meaning AIG may have to resort to fire sales of illiquid assets to generate cash to meet redemptions.142 As then-Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Chairman Martin Gruenberg stated in his dissent of the decision, “Nothing about the liquidity characteristics of AIG’s liabilities and assets has changed to diminish the concerns originally raised by the FSOC.”143 Indeed the FSOC used different, watered-down models and assumptions for evaluating AIG’s potential run risk during the de-designation process under Mnuchin.144 Furthermore, AIG still has a sizable derivatives business, even after this business brought the firm to the brink of collapse. AIG’s derivatives portfolio could transmit stress to its derivatives counterparties, some of which are systemically important financial institutions. And the obstacles to resolving such a large and complex global insurance company would likely aggravate these concerns. Richard Cordray, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau director at the time, summed it up clearly in his dissent: “[M]aterial financial distress at AIG not only could pose, but actually does continue to pose, a threat to the financial stability of the United States.”145 After the decision, AIG no longer faces strong financial safeguards and no longer has a consolidated federal regulator.

Next on the agenda for Mnuchin’s FSOC was dropping the government’s appeal of the federal district court’s decision in the MetLife case. Despite the substantial evidence suggesting the district court judge’s decision was flawed, the FSOC joined MetLife in asking the appeals court to dismiss the case in January 2018.146 The court granted the dismissal.147 As a result, the $700 billion148 insurance company remained de-designated. If the appeals court had ruled in the government’s favor, MetLife’s designation would have snapped back into place and the firm would have again been subject to enhanced safeguards. One troubling element of the decision, aside from the substantive policy concerns, was the voting threshold used to approve this action. By statute, the FSOC is required to meet a two-thirds threshold, with the affirmative vote of the chair, to designate a nonbank SIFI. The same threshold is required to rescind a firm’s designation. In this instance, which for all intents and purposes was a de-designation vote, only a simple majority of the council voted to drop the appeal.149 In both the decision by the council and the federal district court opinion that was being challenged, fidelity to the clear language of the statute and the expressed will of Congress was questionable.

The final domino to fall was the de-designation of $800 billion insurance company Prudential Financial. While AIG and MetLife could argue that they reduced their systemic risk profile, albeit modestly, Prudential could make no such claim. Since its designation in 2013, Prudential has only grown more systemically important. From that point until 2018, the firm increased its assets by more than $100 billion and its derivatives exposures by more than 30 percent.150 Over that period, Prudential’s repurchase agreements increased by 45 percent, and its securities lending activity was up by 13 percent—two activities that exacerbate the risk of runs and increase the complexity and interconnectedness of a firm’s operations.151 Absent the enhanced regulation and oversight that comes with a SIFI designation, financial turmoil at Prudential could be a greater threat to financial stability today than it was when the company became a nonbank SIFI in 2013. Despite the sound reasoning behind the initial decision to designate Prudential, the annual re-evaluations of that decision to keep the designation in place, and the increase in Prudential’s systemic risk profile, the FSOC voted to rescind the SIFI designation in October 2018.152 The decision was a serious mistake on policy grounds but may also have been illegal based on Dodd-Frank’s statutory requirements.153 In stark contrast to the MetLife lawsuit, the public did not have clear legal standing to contest the deeply flawed de-designation of Prudential.

In fewer than two years, the Trump administration’s FSOC released all of the remaining systemic shadow banks from consolidated oversight and enhanced safeguards. The evidence and analysis supporting the de-designations was lacking. This clearly demonstrates the unfortunate truth that too often, cost-benefit analyses and other “evidence-based” requirements constrain regulation but fail to stop inappropriate deregulation. The decision to rescind the designations for AIG and Prudential, while dropping the MetLife appeal, means that roughly $2.1 trillion in insurance assets will not face strong federal supervision, consolidated capital requirements, liquidity rules, stress testing, living wills, and other safeguards.154 As a result, the financial system is undoubtedly more vulnerable to excessive risk-taking in the nonbank sector. Essentially, Secretary Mnuchin and Trump-appointed regulators are claiming that there is not a single insurance company, hedge fund, finance company, or asset management firm whose failure could threaten financial stability. This is a bold pronouncement. The most recent FSOC annual report reveals that the council has not even advanced any nonbank financial company to the third stage of the designation process.155 Firms have been released, and no new firms are being thoroughly analyzed. Not only has the FSOC deregulated designated firms, it also is not actively probing whether other firms could pose systemic risk. Unfortunately, the U.S. economy, workers, families, and savers will bear the costs of a more vulnerable financial system.

Weakening the designation tool

Simply de-designating the existing SIFIs was not enough for Mnuchin. In addition, the FSOC proposed policy changes that would effectively prevent future administrations from designating new SIFIs.156

First, the council proposed factoring in the firm’s likelihood of distress as part of the designation analysis. Only designating firms that are likely to experience distress would render the designation authority useless and, in fact, would make a nonbank SIFI designation a potentially dangerous label.157 It takes roughly three to five years in total for the FSOC to first complete the robust three-stage analytical designation process; for the Fed to next develop tailored enhanced prudential standards that meet the business model and risk profile of the firm; and finally, for the designated firm to come into compliance with the new regulatory framework. There is not a single market-based or regulatory metric that can accurately predict whether a firm is likely to experience material financial distress many years in advance, and if there were, that company would quickly go out of business, given the desire of investors and market participants to avoid any exposure. Capital requirements, liquidity rules, and risk management standards are all prophylactic tools that must be in place well before stress is likely.158

Common sense—and the 2007–2008 financial crisis—make that conclusion abundantly clear. Bear Stearns announced its first ever quarterly loss just three months before it collapsed, while its stock price was trading around $100.159 Its financial position drastically deteriorated over a matter of weeks in early March 2007, before JPMorgan Chase & Co. purchased the company for $10 per share with financial assistance from the Federal Reserve.160 The credit default swap spread on AIG’s debt—a common market-based measure of the likelihood of default—did not flash bright warning signs until a few weeks before AIG was bailed out.161 Moreover, if a designation is perceived to signal that a firm is likely to experience material financial distress, it could exacerbate a run on the firm by its creditors. This could speed up the firm’s demise and increase fear and contagion in financial markets. Congress understood these arguments when it passed the Dodd-Frank Act. The statute states that one of the designation standards is whether material financial distress at a firm could threaten financial stability.162 This statutory standard assumes financial distress at the firm and does not direct the FSOC to consider the likelihood of such distress. This provides another example of the Trump administration ignoring the clear language and framework that Congress enacted.

Another element of the FSOC’s recent proposal calls for the inclusion of time-consuming, litigation-attracting, and in these circumstances uninformative cost-benefit requirements in the designation process. This type of requirement, contrary to the district court’s decision in the MetLife case, is not required by the statute.163 It is simply another way to limit the use of the designation authority. It is easy to quantify the costs of regulation, such as the labor costs associated with compliance and the potential increase in cost of funding. It is difficult to quantify the precise benefits of a crisis averted or mitigated by regulation.164 As a result, cost-benefit analyses tend to exhibit bias against regulation by underestimating social benefits. This exacerbates a severe obstacle with financial regulation: It is difficult to see the crises that did not happen and to see the fruits of preventative measures. Furthermore, financial regulation cost-benefit analyses are easily second-guessed by courts.165

The FSOC’s proposal also eliminated the first of the three stages in the SIFI designation process. Currently, firms that trigger the quantitative threshold in the first stage automatically advance to the second stage, where they receive closer scrutiny using public information and information already available to regulators. The council may then vote to advance a firm into the third stage, where the council conducts an in-depth analysis of the firm. By eliminating the first stage of the process, the FSOC will not automatically review a class of firms for designation. Instead, the FSOC will have to proactively identify a firm and vote to advance it into the first stage of the process. This, again, creates a bias toward inaction and actually provides less clarity to the universe of nonbank financial companies as to what quantitative measures and thresholds the council uses. Future administrations will be deprived of years’ worth of preliminary research and analysis on nonbank financial companies and their evolving business models and risk profiles because the FSOC under Secretary Mnuchin is unlikely to vote any firm into the new first stage of review.

Former Treasury Secretaries Tim Geithner and Jack Lew and former Federal Reserve Chairs Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen forcefully opposed these proposed changes in a comment letter. The group stated, “These changes would make it impossible to prevent the build-up of risk in financial institutions whose failure would threaten the stability of the system as a whole.”166

Faux activities-based emphasis

In an attempt to make it look like the council is, in fact, taking some action to mitigate threats to financial stability—and not simply deregulating firms and weakening the authority to designate firms—the Mnuchin FSOC proposed executing an “activities-based” approach to financial stability regulation.167 Instead of focusing on firms that could pose risks to the financial system, the FSOC would analyze potential systemic activities. This purported shift in strategy is a misdirection—merely a talking point without any underlying value. The FSOC does not currently have the statutory authority to regulate activities. Its only activity-related authority is to issue nonbinding recommendations to the primary regulator of a given activity—if such a regulator exists.168 In the proposal to implement this approach, the council emphasizes that it would provide a high level of deference to the primary regulator of a given activity. This type of hands-off approach leaves financial stability oversight to a disparate set of regulators. It is a tacit endorsement of the pre-crisis approach to systemic risk. It’s worth pointing out that, despite the activities-focused rhetoric, the FSOC has failed to identify a single systemically risky activity or initiate the process for issuing a nonbinding recommendation during Mnuchin’s tenure.

The ability to directly regulate systemic activities could be an important complementary tool to the FSOC’s designation authority. It should not be viewed as a substitute or even the desired primary tool used to combat systemic risk, however. An activities-based approach looks at a firm’s activities in isolation and ignores how the mix of activities at a firm could pose a risk to the system if the firm were to fail.169 The activities-based approach, given its focus, tends to discount the impact that a firm’s size, total leverage, and interconnectedness would have on its systemic risk profile. This shortcoming is brought into focus when comparing the potential regulatory toolkit for both the entity approach and the activities approach. Under the entity approach, a designated shadow bank would face consolidated capital and liquidity requirements, enterprisewide risk management rules, stress testing, living wills, and other rules that focus on the totality of the firm’s risk profile. These consolidated tools are not available under the activities-based approach. Instead, measures such as capital and liquidity rules are only applied to a particular activity, not the entire firm, while other tools such as stress testing and living wills are not envisioned in any form. Moreover, it is easier for regulators to identify systemic firms ex ante.170 Analyzing a firm’s size, complexity, interconnectedness, reliance on short-term funding, and other systemic risk factors is a more manageable undertaking than predicting which activities will threaten systemic risk ahead of time. As previous crises make clear, due to opacity, financial engineering, or flawed consensus assumptions, the systemic nature of an activity is only clear after the crisis hits. Moreover, the regulatory fragmentation in the United States makes an activities-based approach difficult to implement.171 There are certain activities that fall outside of the reach of federal regulators, while other activities have multiple regulators with overlapping jurisdictions. These realities are clear obstacles to a successful activities-based approach.172

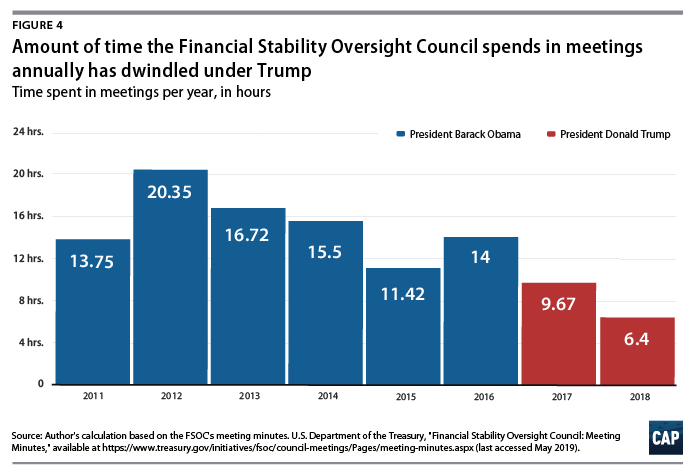

Lack of oversight

Aside from the previously outlined deregulatory actions, the FSOC has completely neglected systemic risk oversight. During the Trump administration, the council’s annual meeting time has decreased substantially. From 2011 to 2016, the average cumulative time that the council met in a given year was 15 hours and 17 minutes.173 The average annual meeting time dropped by almost 50 percent, to eight hours and two minutes, over the past two years.174 Notably, the FSOC met for fewer than seven hours in 2018, which is almost five hours less than the lowest point during the Obama administration.175

Moreover, Secretary Mnuchin has dropped certain financial stability inquiries that were started under the Obama administration. For example, in 2016, the council formed a working group to investigate the potential financial stability risks posed by highly leveraged hedge funds. Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA) recently asked Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell, a voting member of the council, for an update on the working group’s progress. Chairman Powell was unfamiliar with the working group and could not provide an update on its work.176 In fact, the public has not received any word on the working group’s progress since November 2016, when the working group outlined open questions that needed to be addressed, particularly concerning the inadequate nature of data collected on hedge funds.177 Mnuchin has evidently ceased this line of work. It is a troubling development, particularly since hedge fund leverage has grown significantly over the past two years, based on data reported by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.178 Hedge funds are also involved in the substantial growth of leveraged loans and collateralized loan obligations.179

The lack of financial stability oversight and action comes at a time when new risks in the financial system are building and existing risks remain inadequately addressed. The substantial increase in corporate debt and, in particular, leveraged lending could meaningfully aggravate the next economic downturn.180 Business debt levels relative to gross domestic product are historically high.181 Leveraged lending, or loans to companies that already have significant debt, grew by 20 percent in 2018 and now stands at more than $1 trillion.182 In a downturn, these debt levels could lead to a wave of corporate defaults and put pressure on systemically important financial institutions both directly and indirectly. Corporate debt markets cut across multiple regulatory jurisdictions, making it an issue ripe for FSOC oversight. The council has discussed it at recent meetings but has not issued any in-depth reports or made any recommendations to regulators regarding a course of action. Other issues, including the ongoing risks posed by runnable short-term funding markets, have received little attention. According to the Fed, there is more than $14 trillion in runnable liabilities outstanding in the U.S. financial system.183 While some postcrisis actions have decreased the vulnerability of the financial system to runs, few steps have been taken to directly reform the markets themselves. Several other potential financial stability risks, including cybersecurity, financial technology, and the lack of adequate data on opaque sectors of the financial system, have not received necessary attention or action.

Eroding institutional capabilities

Secretary Mnuchin and Trump-appointed financial regulators have taken steps to erode the FSOC as an institution. Over the past two years, the council’s budget and staffing have been slashed. The budget has been reduced by 15 percent, and the target staffing level has been lowered from 36 full-time staffers in the final year of the Obama administration to just 18 staffers in the latest FSOC budget—a 50 percent cut.184 Furthermore, the Trump administration has made a mockery of the independence Congress intended to afford the Office of Financial Research. The OFR director is supposed to have discretion over its budget, while only consulting with the treasury secretary. Instead, Secretary Mnuchin directed the OFR to cut its budget by 25 percent and its staffing level by almost 40 percent.185 Mnuchin installed a Treasury staffer to serve as acting director,186 and President Trump has nominated for director a former House staffer who worked to repeal the agency.187 These cuts do not save taxpayers a dime in direct spending because both offices are funded through fees assessed on bank and nonbank SIFIs. In essence, Secretary Mnuchin has chosen to give money back to systemically important financial firms at the expense of systemic risk oversight. However, the cuts do weaken the institutional capabilities of the council and mean that a future administration would not only have to undo harmful policy changes but would also have to rebuild the FSOC and the OFR from the ground up.

Secretary Mnuchin’s first two years leading the FSOC are a complete abdication of the council’s important financial stability role. He, along with the other Trump-appointed financial regulators, have cast aside the council’s tools, rejected its mission, and ignored the clear command of statute. They have deregulated firms such as AIG, advanced proposals to weaken the FSOC’s tools for future administrations, shut down important systemic risk inquiries, and sought to dismantle the institutional capabilities of the council from within. The financial system is more vulnerable as a result—increasing the chances that workers, families, and savers will bear the brunt of another financial collapse.