The April arrival of the Central American caravan at the southern U.S. border once again placed the nation’s focus on individuals and families who traveled thousands of miles to seek asylum in the United States.1 The Trump administration is mischaracterizing the caravan as evidence of an out-of-control border crisis requiring a multifaceted and aggressive response—even though federal law enforcement apprehensions at the southern border in fiscal year 2017 remain at a near 46-year low since fiscal year 1972.2 The administration is using the caravan to justify several decisions, including sending thousands of National Guard troops to the border and making draconian changes to policies relating to asylum and criminal prosecutions. These changes are designed to expedite the path to deportation by circumscribing an individual’s right to seek asylum.3

In May 2018, the administration announced a “zero-tolerance policy” to prosecute anyone crossing the border, including those who may seek asylum.4 One predictable result of this new policy is that families apprehended at the border are being separated, with parents being referred by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for prosecution and children being sent to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement. Recent testimonies by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials suggest that during a 13-day span in May, DHS may have separated 658 children from parents.5

Many asylum-seekers in the United States are from Latin America, especially the Northern Triangle region of Central America—El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.6 They are fleeing because their home countries continue to be plagued with violence—much of it gang-related—as well as economic and political instability. Among those fleeing, many are women; children who may be unaccompanied or traveling with a parent; and LGBTQ people.7 Turning these individuals and families back or actively deporting them to their home countries—sometimes after first criminally prosecuting them and sentencing them to time in U.S. federal prison—may mean returning them to places where they may face persecution, displacement, and, in some cases, even death.8

The Northern Triangle is still one of the most dangerous regions in Latin America

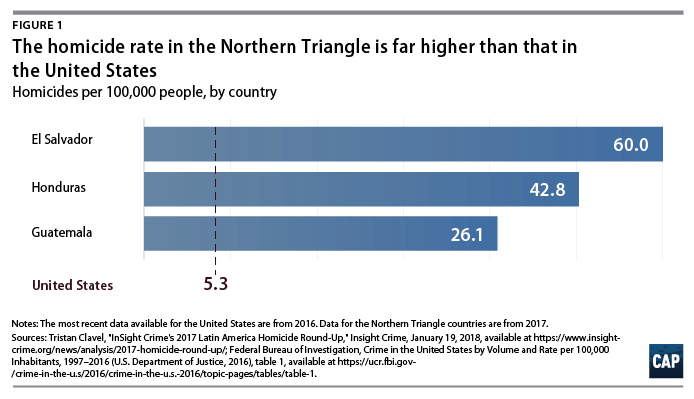

The Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala remain among the most dangerous countries in the world, despite targeted efforts over the past few years to combat violence.9 For example, in mid-2016, El Salvador implemented “extraordinary measures,” including cutting off contact between imprisoned top gang leaders and the outside world to prevent them from issuing orders.10 The United States invested nearly $2 billion during fiscal years 2015 through 2017, with bipartisan support to improve citizen security and the rule of law in Central America. This investment went hand in hand with the region’s own efforts to combat various challenges: the Alliance for Prosperity initiative.11 While homicide rates showed signs of improvement in these three countries in 2017, the epidemic of violence is far from over.12 In mid-2017, for example, several news outlets reported that El Salvador saw a disturbing increase in killings targeting relatives of security forces in retaliation for implementing tough measures in the prison systems, which raises questions about whether the downward trend in violence is reversing.13 Most notably, the total number of homicides in the first quarter of 2018 is 14 percent higher when compared with the same time frame in 2017.

Women, children, and LGBTQ people are unsafe in the Northern Triangle

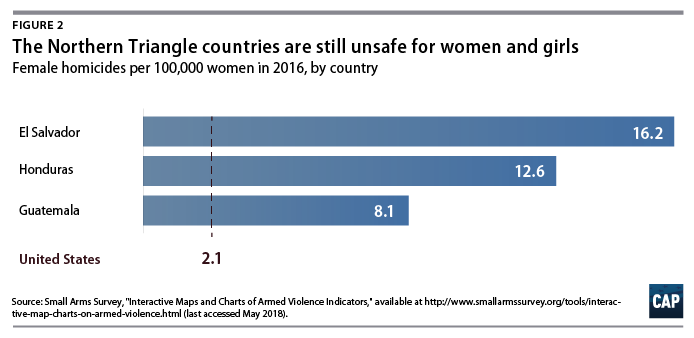

Women and children, especially girls, as well as LGBTQ people continue to face high levels of severe and persistent danger from gender-based violence in the Northern Triangle countries. According to data released by the Small Arms Survey, El Salvador and Honduras were among the 10 countries not currently involved in armed conflict with the highest rates of femicide—the murder of women—in 2016.14 While the 2017 statistics show a slight decrease in that rate for both countries, the number of female homicides is still very high.15 For example, El Salvador reported 469 femicides in 2017—down from 524 in 2016—but this means that on average, more than nine women and/or girls were killed every week in 2017.16 Women and children in the Northern Triangle region also face brutal physical and sexual violence at the hands of gang members and other individuals.17 Additionally, LGBTQ people are also vulnerable to similar abuses and threats in these countries.18 Often, survivors do not have any avenues to pursue justice, because there is a high level of impunity and lack of protections in these countries.19 Stories shared by women, children, and LGBTQ people traveling in the caravan cited sexual abuse, severe stress and fear, domestic violence, and rape as reasons for fleeing their countries.20 These include Nelda, a teenager who left Honduras with her mother and little sister to escape her sexually abusive uncle, a man with gang ties. He threatened to kill them if they did not withdraw their police report against him.21

Asylum applications by citizens of Northern Triangle countries are skyrocketing

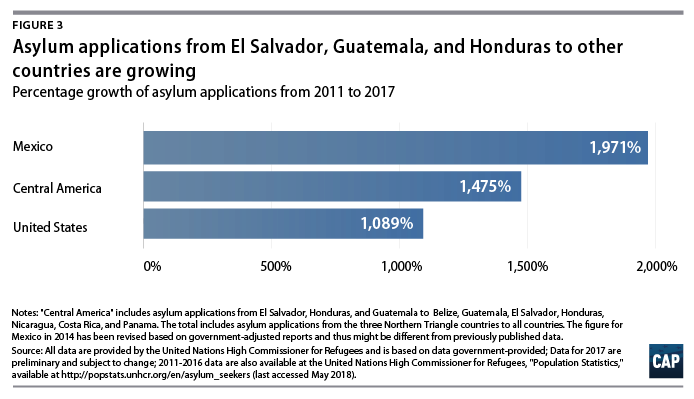

Hundreds of thousands of people have left the Northern Triangle region in the past few years and sought asylum elsewhere. According to the data collected by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the total number of asylum applications registered by citizens of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala to other countries increased more than elevenfold from 2011 through 2017.22 During that same time frame, there has been a 1,500 percent increase in people from these three countries seeking asylum in Central American countries such as Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama. The largest percentage increase in asylum applications from people in these three countries is seen in Mexico, with an increase of 1,970 percent. Over this same period, the United States experienced an increase of 1,089 percent in asylum applications from Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Guatemalans. The Northern Triangle countries were among the five countries with the highest number of citizens seeking asylum in the United States in 2016. The UNHCR recently reported a 58 percent increase from 2016 to 2017 in registered asylum-seekers and refugees from the Northern Triangle region, with more than 294,000 people seeking safety globally.23 Additionally, the UNHCR noted that from 2011 to 2017, 350,000 people from this region had filed for asylum worldwide, with more than one-third—130,500—applying in 2017.

In addition to violence, there are other emerging issues that may affect the number of people from these Northern Triangle countries seeking asylum today. For example, reports claim that some Hondurans are leaving their country due to fear of instability after the highly contested election in 2017.24 Postelection demonstrations were met with excessive force by the Honduran government resulting in detainment, death, and injuries; the media dubbed these events as the “worst political crisis since a coup in 2009.”25 In one particular incident, officers, most likely military police, fired their guns and killed five unarmed protestors who were blocking a road and hurling rocks at them.26

Many internally displaced people in Northern Triangle are fleeing violence

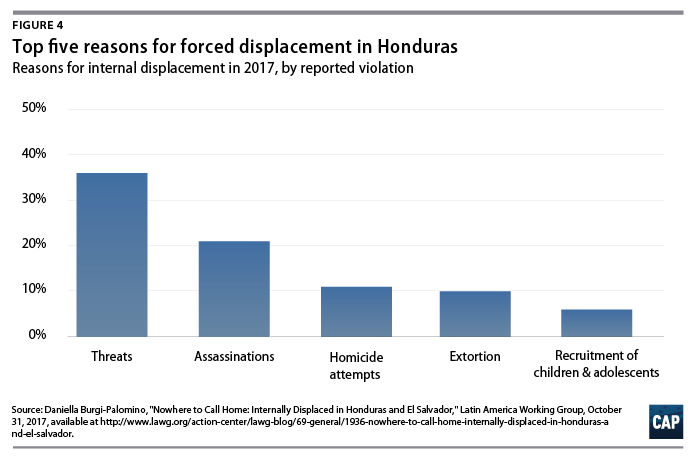

While the significant numbers of people fleeing the Northern Triangle countries are evidence of the extreme conditions in the region, many others have fled from their homes and are internally displaced elsewhere in their home countries for those same reasons. Estimates by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre suggest that each of the Northern Triangle countries has many internally displaced people (IDP).27 Among the three countries, only Honduras officially recognizes IDP as an issue, and even there, IDPs are likely undercounted because they are often not willing to come forward fearing retaliation from gangs.28 According to a 2017 survey by the National Commission on Human Rights, the top reasons for internal displacement in Honduras are threats, assassinations, and homicide attempts.29 Yessenia, a 56-year-old teacher from Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, left her job and home for fear of reprisal after she witnessed a group of young men beating one of her students.30 There are many like her; the possible large presence of IDP, many of whom attribute their status to human right abuses, highlights the extent of the problem in Honduras.

The emerging refugee crisis out of Venezuela serves as a wake-up call

Venezuela, once a middle-income developing country, is now collapsing. The nation is crippled by a worsening economic crisis; skyrocketing levels of violence; dwindling supply of necessities such as food and medicine; and the authoritarian rule of President Nicolás Maduro.31 The Venezuelan government’s mismanagement of the economy and the evisceration of democratic institutions has been blamed for the nation’s failures and widespread lawlessness.32 Maduro’s recent “re-election” through a fraudulent process roundly denounced by the international community indicates continuation of the same failed economic policies and unbridled violence.33

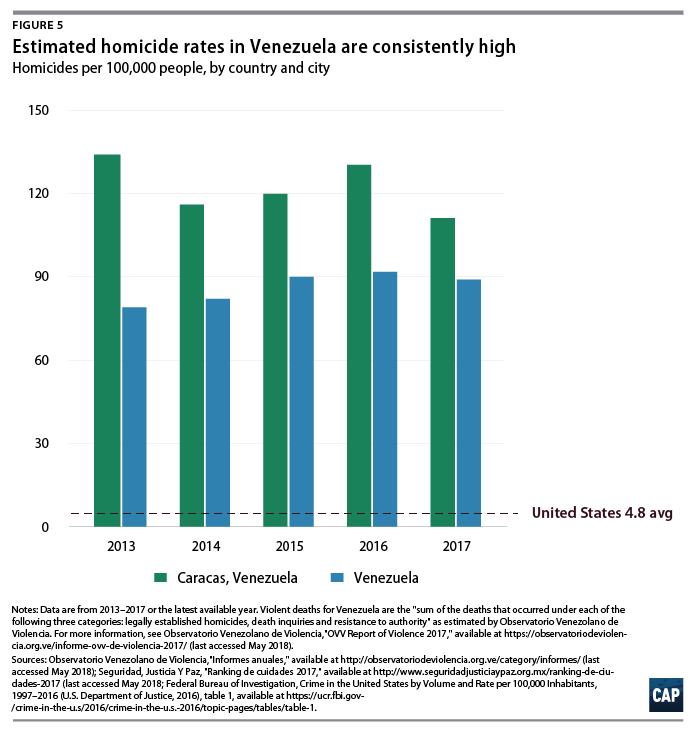

The data on homicides are murky because the government stopped releasing comprehensive crime statistics years ago.34 But data collected by independent organizations rank Venezuela as the most violent country in the Latin American and Caribbean regions, and Caracas, its capital, as one of the most murderous cities in the world.35 With women and girls being victims of homicide at a rate of 24.5 out of every 100,000 women, Venezuela’s femicide rate in 2016 was surpassed only by Jamaica when looking at countries not currently involved in an armed conflict.36

In short, Venezuela is a neglected humanitarian crisis.37 Venezuelans are fleeing their country in record numbers. According to the UNHCR, the number of Venezuelans applying for asylum around the world increased from 963 in 2012 to 34,348 in 2016—a thirty-fivefold increase.38 Reports suggest that at least a million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring Colombia where many of them lack legal status, and another 52,000 have reached Brazil since 2017.39 According to data from the UNHCR, the number of Venezuelans seeking asylum in the United States grew by nearly 2,500 percent from 2012 through 2016, making Venezuelans the fastest-growing group of people seeking asylum in United States.40 Even as Venezuelans are facing dire circumstances, including growing starvation, the Maduro government has refused to accept direct assistance.41 Recently, the United States announced that it will provide $16 million in humanitarian assistance to help Venezuelans who have fled their country—assistance that includes contributions to the UNHCR for its work in the region.42 While providing vital funds will help mitigate some of the problems, weakening the U.S. asylum systems would worsen situations for those seeking protection and would directly contradict the Trump administration’s protestations of standing with the people of Venezuela.43

Conclusion

The situation in Latin America is shifting, but the Northern Triangle region is still considered to be one of the most dangerous regions within Latin America, one that is producing significant numbers of refugees. But the Trump administration, rather than recognizing the need to do more to stabilize countries in the region and protect those seeking asylum, is taking actions that will actually worsen the situation. Last month, President Donald Trump floated the idea of cutting U.S. aid to Honduras in response to the caravan—aid that the United States provides in an effort to increase stability and security in Honduras to deter future migration.44 And by ending Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for both Honduras and El Salvador, the administration has placed a total of about 250,000 people who have lived and worked lawfully in the United States for nearly 20 years at risk for deportation in the months ahead.45 Potentially sending hundreds of thousands of people to their home countries, which are in no position to reintegrate them, will only make matters worse for the region.46 Ending TPS has the potential to undo any meager progress toward stability that these countries have made.

Furthermore, mishandling asylum cases and deterring people from applying for asylum by criminally prosecuting people and separating children from their mothers is not just dangerous for those seeking asylum but inhumane as well.47 All these actions run contrary to what the United States should be doing to improve security and economic conditions in Latin America, provide a safe haven for refugees, and encourage a regional solution to tackle these issues.48

Silva Mathema is a senior policy analyst of Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Adam Isacson from the Washington Office on Latin America; Daniella Burgi-Palomino from the Latin America Working Group; and Tom Jawetz, Philip E. Wolgin, Dan Restrepo, and Michael Werz from the Center for American Progress for reviewing this brief; Anneliese Hermann from the Center for American Progress for providing research support on Venezuela; and Alice Farmer, Noha Khalifa, and Ivan Cardona from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees for providing additional data on asylum-seekers.