See also: To Fight Inequality, Support Women’s Work by Judith Warner

Has the rise of women’s earnings increased inequality in the United States? This column provides evidence that the answer is a resounding “no.” In fact, women’s earnings have significantly slowed the growth of inequality.

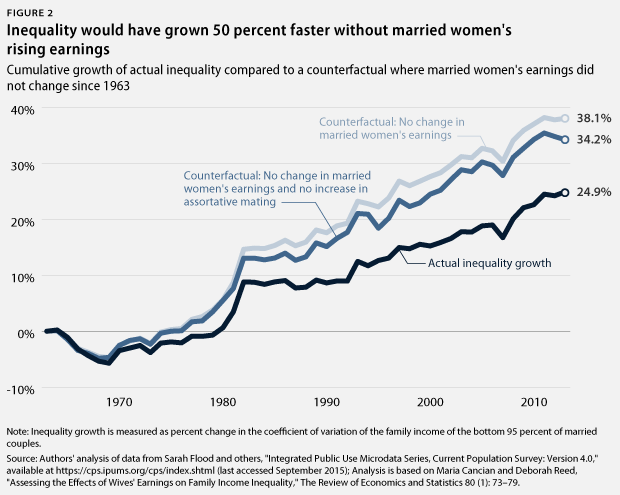

In the past 50 years, married women’s earnings have grown fivefold. During that same time span, income inequality among married couples grew 25 percent. If married women’s earnings had not grown, however, inequality would have risen 38 percent. In other words, inequality would have grown nearly 53 percent faster if married women’s earnings had not increased.

Our currently unacceptable levels of income inequality would be even more unacceptable if not for women’s growing earnings. The following analysis suggests—as convincingly argued in Center for American Progress’ Senior Fellow Judith Warner’s report, “To Fight Inequality, Support Women’s Work”—policies aimed at increasing women’s labor force participation, which in turn drives women’s earnings, would help to reduce income inequality.

Inequality trends

Income inequality has grown rapidly over the past 30 years, especially at the very top. But there has also been a substantial increase in inequality throughout the income distribution, including among the bottom 95 percent of married couples. We focus on the bottom 95 percent because of data consistency issues; see the Methodology for more details.

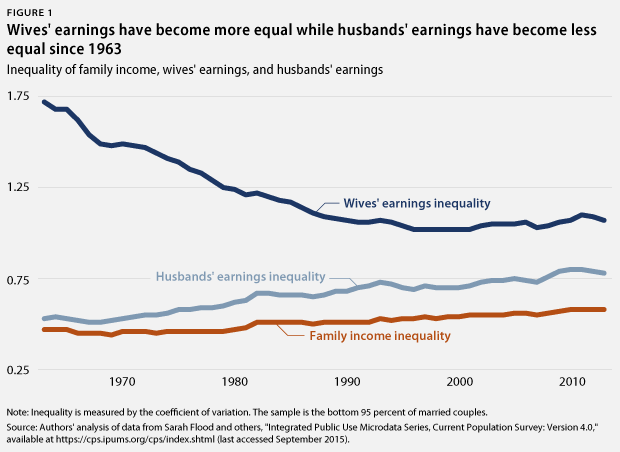

Figure 1 displays inequality of family income, married women’s earnings, and married men’s earnings. Income inequality grew 25 percent over this 50-year period, and married men’s earnings display a similar trend. Yet, married women’s earnings stand out for both being more unequal compared with men’s earnings and also for rapidly equalizing over the past 50 years. Married women’s earnings were about three times as unequal as married men’s earnings in 1963 but were only 37 percent more unequal in 2013. In other words, wives’ earnings have grown more equal while husbands’ earnings have grown more unequal.

The higher level of married women’s earnings inequality and its rapid decline result from the fact that we measured earnings rather than hourly wages. Higher labor force participation by married women greatly reduces earnings inequality because fewer married women have zero earnings even if their wages have become more unequal.

How married women’s earnings reduce income inequality

The question of how rising female labor force participation and earnings affect inequality has received increasing attention recently following the publication of much-discussed 2014 article by University of Pennsylvania economist Jeremy Greenwood and others.

The article shows that the rising trend of “assortative mating”—defined by Greenwood and his co-authors as the rising correlation between husbands’ and wives’ educational levels—increased income inequality. Importantly, they also show that the rise in assortative mating would have had no effect on inequality if married female labor force participation had not also risen.

But because Greenwood’s article is about the effect of assortative mating on inequality, it does not consider the overall effect of married women’s labor force participation. Indeed, the falling inequality of married women’s earnings displayed above should mechanically reduce inequality. The question, then, is which effect is stronger?

In a 1998 article in The Review of Economics and Statistics, one of the top peer-reviewed economics journals, Maria Cancian of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Deborah Reed then of the Public Policy Institute of California laid out an approach for measuring how changes in married women’s earnings affect changes in inequality. They did this by constructing a counterfactual level of inequality in 1989 based on what would have happened if married women’s earnings had not changed since 1979. Cancian and Reed showed that the counterfactual level of inequality grew 27.9 percent more quickly than the observed level between 1979 and 1989.

The analysis used in this column (see Methodology below) expands on the work of Cancian and Reed and looks at the years 1963 through 2013, a period over which women’s real earnings grew fivefold. Figure 2 displays the comparison between observed inequality and the counterfactual level. Based on these numbers, inequality would have grown 38.1 percent between 1963 and 2013 if married women’s earnings had not changed, compared with the observed 25 percent growth. Without changes in women’s earnings during that 50-year span, inequality would have grown 52.6 percent faster.

In our data, we do see an increase in assortative mating—measured this time by the correlation between the earnings of married men and married women. The correlation, in this case, rises from slightly negative at -0.09 to slightly positive at 0.07. As Cancian and Reed argue, it is unclear what portion of the increase should be attributed to married women’s earnings since married men’s earnings are also responsible for the growing correlation.

Yet, even when we assign the entire increase in assortative mating to married women’s earnings by setting the correlation at its 1963 level in the counterfactual, inequality would still have grown 37.8 percent faster without the increase in married women’s earnings. Assortative mating’s effect on inequality has thus been a drop in the bucket compared to the powerful equalizing effect of changes to married women’s earnings.

This analysis shows that married women’s rising earnings have been a critical countervailing force against the growth of income inequality over the past 50 years.

Methodology: How we got to our numbers

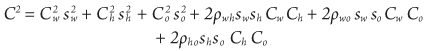

Using Cancian and Reed’s approach, we can decompose income inequality among married couples with the following equation:

Where w indexes variables that correspond to married women, h indexes variables that correspond to married men, and o indexes variables that correspond to nonearnings cash income, meaning everything from Social Security to dividends.

Variables C represent inequality as measured by the coefficient of variation, which is the ratio between a standard deviation and a mean. Variables s represent the share of all family income that a type of income makes up (i.e., sw equals (μw)/(μw + μh + μo)). Finally, variables ρ represent the correlation between two types of income. Notably, ρwh measures assortative mating.

Cancian and Reed provided a method for calculating how married women’s earnings contributed to income inequality between two years by constructing a counterfactual where married women’s earnings did not change. Therefore, we hold Cw and μw at their 1963 levels. When we assign the entire growth of assortative mating to changes in married women’s earnings, we also hold ρwo and ρwh at their 1963 levels.

Our data come from extracts of the March Current Population Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau, available from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series from the University of Minnesota. We use each extract between 1964 and 2014, which correspond to data representing the years between 1963 and 2013. Like Cancian and Reed, our sample consists of married couples where both the husbands and wives are between the ages of 25 and 64.

The U.S. Census Bureau uses a procedure known as “top-coding” in which it does not report the actual earnings of persons with very high incomes in order to preserve anonymity. Because top-coding procedures have been inconsistent, we eliminated married couples in the top 5 percent of the earnings distribution to prevent changes in top-coding from influencing the evolution of the earnings distribution. Thus, our analysis only explains inequality among the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution.

We attempted to replicate Cancian and Reed’s findings, which did include the top 5 percent. Cancian and Reed showed a 10.9 percent increase in inequality between 1979 and 1989 compared to a counterfactual of 14 percent without changes in married women’s earnings. Therefore, inequality would have grown 27.9 percent faster without changes in married women’s earnings. Our data show a 12.1 percent increase in inequality compared to counterfactual growth of 15.7 percent, meaning inequality would have grown 29.6 percent faster without changes in women’s earnings. The likely cause of this small difference was the way Cancian and Reed adjusted their data for top-coding. Nevertheless, our replication results are qualitatively similar.

Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst for American Progress’ Middle-Out Economics project.