On April 7, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit dismissed a lawsuit that challenged the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA. The court’s unanimous ruling in that case, Crane v. Johnson, is ominous for those who turn to the courts in a last-ditch attempt to block the Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, immigration policies announced by President Barack Obama in November.

The 5th Circuit held in Crane that neither agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement nor the state of Mississippi had standing to challenge the DACA program. Most directly, the Crane ruling ensures that DACA, which has already benefited 640,000 long-term residents brought here as children, will remain in effect. The ruling means the government can continue to focus its limited enforcement resources on such priorities as national security, public safety, and border security. It also ensures that hundreds of thousands of DACA recipients can continue to work lawfully and help grow our economy without living under constant threat of deportation.

The ruling also has important implications for a lawsuit filed in December by Texas and other states that seeks to block the more recent deferred action memoranda issued by the DHS. These DHS immigration policies build on the 2012 DACA policy to make millions of additional low-priority undocumented immigrants eligible to seek temporary, albeit revocable, protection from deportation. Like DACA, these policies work by prioritizing limited enforcement resources to focus on serious criminals and recent arrivals, rather than low-priority immigrants such as long-resident DREAMers and the family members of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. More specifically, the 2014 announcements expand eligibility for DACA and establish a new program, Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, or DAPA. The latter allows parents of U.S. citizens and parents of lawful permanent residents to request consideration for deferred action if the parents have lived continuously in the United States since January 1, 2010, and meet several additional requirements.

The Texas lawsuit challenges DAPA and the 2014 expansion of DACA, though not the original 2012 DACA. Like the plaintiffs in the Crane case, Texas argues that the challenged immigration programs violate both the Administrative Procedure Act, or APA—which governs the procedure for issuing federal regulatory policies—and the DHS’ constitutional obligation to enforce the immigration laws. The crux of the lawsuit’s constitutional claim is that, by prioritizing some immigrants for removal but exercising discretion with others and enabling them to remain in the United States temporarily, DACA and DAPA amount to an abdication of the DHS’ duty to enforce the law. And like the state of Mississippi in Crane, Texas seeks to demonstrate that it has legal standing to challenge the programs by arguing that the programs will harm its taxpayers.

In February, U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen ruled in favor of Texas and temporarily enjoined the DHS policies, blocking them from going into effect. Judge Hanen’s vitriolic 123-page opinion concluded the following: (1) The state of Texas had standing; and (2) Texas was likely to succeed with its claim that the government had violated the APA notice and comment requirements.

The federal government has appealed Judge Hanen’s preliminary injunction to the 5th Circuit. The Crane decision now considerably bolsters this appeal by undermining both Judge Hanen’s novel theory of standing and the premise for his APA ruling.

Texas’ standing in further jeopardy

In Crane, the 5th Circuit ruled that Mississippi lacked standing to challenge DACA because it could not demonstrate that DACA was actually costing the state any money. First, as the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund pointed out, the 5th Circuit pointed out that Mississippi had failed to show that DACA—as opposed to unauthorized immigration itself—imposed any costs on the state. Second—and of direct relevance to the Texas case—the court found that Mississippi had considered only the fiscal costs, not the fiscal benefits, to the state. As the court noted, a conclusion could just as easily be drawn that the DHS’ efforts to prioritize and reallocate resources could result in removing greater numbers of high-priority immigrants who “impose a greater financial burden on the state.” That, in turn, continued the court, would lead to a net “reduction in the fiscal burden on the state.”

Texas, in arguing for standing to challenge the 2014 DHS policies, avoids the first problem of identifying a specific potential cost from the immigration programs, but it runs directly into the second problem identified by the 5th Circuit—specifically, failing to consider the programs’ fiscal benefits.

Texas argues that deferred action recipients are eligible for driver’s licenses and that Texas taxpayers partially subsidize the cost of processing applications for those driver’s licenses. Judge Hanen, in finding that Texas had standing to challenge the policies, accepted a declaration from the assistant director of the Driver License Division of the Texas Department of Public Safety, or DPS. The declaration estimated that granting deferred action recipients driver’s licenses would cost the state millions of dollars, a concrete cost of the program itself.

Even without the 5th Circuit decision in Crane, Judge Hanen’s standing theory was on shaky ground. First, the claimed millions of dollars in costs to Texas are belied by the state’s own budget documents, which suggest that the state actually generates a profit by processing license applications. Those documents indicate, for example, that it costs the Texas DPS less than $21 to process a license, even though it charges a $25 fee.

Second, if a state could establish standing simply by showing that a favorable immigration decision by the federal immigration agency could have a net negative fiscal impact on the state, then the state in which a given noncitizen lives would have standing to challenge individual grants of deferred action. Indeed, it would provide states the standing to challenge every single approval made by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS, of any immigration application—including asylum—that could make a person eligible for state benefits. For example, a French citizen who obtains permanent residence via marriage to a U.S. citizen living in Texas will become eligible for a driver’s license. Under this theory, Texas would have standing to challenge the grant of permanent residence to the French spouse.

Putting aside both the flaws in how Texas reported the costs of its driver’s licenses and the extreme results that Judge Hanen’s standing theory would logically produce, the 5th Circuit’s decision in Crane exposes perhaps the most serious defect in Judge Hanen’s standing theory: He considered only the potential cost side of the ledger. In Crane, the court made clear that the proper way to analyze standing is to evaluate any net fiscal effects by considering both sides of the balance sheet—the potential fiscal costs and the potential revenues from the challenged action. Even accepting Texas’ full estimate of costs from granting driver’s licenses, it is clear that these costs would be more than offset by the additional tax revenues generated by the very immigrants who might apply for the licenses. Yet Judge Hanen refused to consider these revenues.

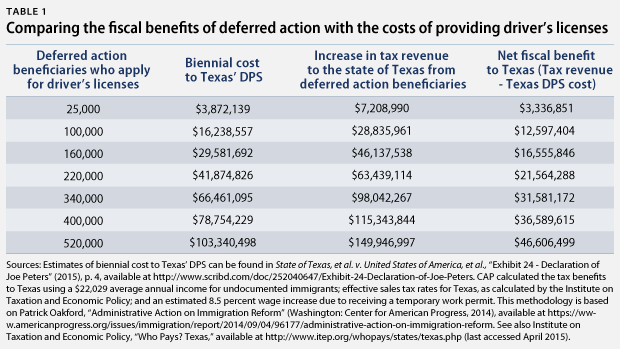

In fact, as demonstrated in Table 1 below, even if all 520,000 of the estimated potential deferred action recipients applied for driver’s licenses—which is highly unlikely—and even if all of the DPS estimates are accepted, there would still be a net fiscal gain of nearly $47 million to the state’s general revenues. Given this finding, Texas’ narrow claim of a concrete, particularized harm to its taxpayers from the DHS deferred action policies does not hold up. Never mind the fact that the analysis below does not reflect the obvious public safety gains from having licensed, insured motorists on Texas roadways. Given the absence of an actual fiscal harm to the state—indeed, a likely net fiscal benefit—Texas’ standing claim collapses.

Administrative Procedure Act claim undermined

Just as importantly, the Crane opinion also undermines Judge Hanen’s ruling on the APA. Judge Hanen issued his preliminary injunction based solely on his assessment that the two 2014 DHS deferred action announcements, DAPA and the expansion of DACA, required formal APA notice-and-comment rulemaking. That view depended on Judge Hanen’s belief that the DACA and DAPA programs amounted to formal rules that mandated that the adjudicators of DAPA and DACA applications grant deferred action to anyone eligible, without any discretion.

To the contrary, however, like the original DACA program that was challenged in Crane, the expanded DACA and DAPA programs explicitly direct adjudicators to engage in a case-by-case discretionary evaluation of the merits. This issue of case-by-case consideration is central to whether public notice and comment are required. The APA expressly exempts “general statements of policy” from its notice-and-comment requirements. And the U.S. Supreme Court in Lincoln v. Vigil interpreted this exemption as including “statements issued by an agency to advise the public prospectively of the manner in which the agency proposes to exercise a discretionary power.”

That is precisely what the DACA and DAPA programs do—advise the public prospectively about what criteria USCIS will use in exercising its discretionary power to grant deferred action in individual cases. Judge Hanen’s assumption that these programs amount to mandatory rules or create binding norms on the adjudicators directly conflicts with the evidence. The language in both the 2012 DACA memorandum and the 2014 DACA and DAPA memoranda expressly instructs USCIS to exercise individualized, case-by-case discretion. As carefully detailed during recent author congressional testimony, there is also this: (a) the absence of any evidence suggesting that USCIS adjudicators are systematically disobeying the secretary of homeland security’s instructions; (b) specific affirmative examples of DACA denials on discretionary grounds in a government affidavit submitted to the court; (c) specific explanations in the same affidavit of the additional discretion required just to apply the threshold criteria; (d) the government’s use of a standardized denial template that specifically lists discretion as a ground for denial; and (e) an absence of support for the speculation that USCIS adjudicators will refuse to exercise discretion when at some future time they begin to decide DAPA requests.

Like the decision by the federal District Court for the District of Columbia, which also dismissed a challenge to the 2012 and 2014 deferred action memoranda in December, the 5th Circuit decision in Crane expressly rejects the plaintiffs’ claim that deferred action is mandatory. In that ruling, the 5th Circuit states, “The Napolitano Directive [the 2012 DACA memorandum] makes it clear that the Agents shall exercise their discretion in deciding to grant deferred action, and this judgment should be exercised on a case-by-case basis.” It then adds that, “The 2014 supplemental directive, which also supplements DACA, reinforces this approach to the application of deferred action.”

This conclusion by the 5th Circuit—that DHS retains discretion in choosing to grant or not to grant deferred action—nullifies the entire premise of Judge Hanen’s argument—that DACA and DAPA are not discretionary and thus require notice and comment rulemaking under the APA.

Conclusion

Judge Hanen’s rulings on both the standing and the APA issues—specifically, that DACA and DAPA are not discretionary and thus require notice and comment rulemaking under the APA—cannot be squared with either the evidence in the record or the governing legal principles. The 5th Circuit’s decision in Crane—a unanimous ruling by two Republican appointees and one Democratic appointee—exposes several of these flaws, vindicates the DHS deferred action programs, and should weigh heavily when the same court decides the pending appeal in the Texas case.

Marshall Fitz is the Vice President for Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress. Stephen Legomsky is the John S. Lehmann University Professor at the Washington University School of Law and the former chief counsel of USCIS in the Department of Homeland Security.