Introduction and summary

Over the past several decades, as concentrations of income and wealth have approached historic levels, taxes on the very wealthy have not kept up. In fact, taxes on the ultrarich have gone in the opposite direction. Tax changes enacted since the 1980s, including the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) passed in December 2017, have eroded taxes on the people who have benefited the most from the economy, thereby aiding and abetting the widely acknowledged and troubling increase in wealth inequality. These changes have worsened a structural defect in the U.S. tax code—specifically, its failure to tax massive accumulations of wealth.

The result is that America’s tax code no longer adheres to the core principle of ability to pay—the idea that taxes should be based on a person’s capacity to pay taxes.1 Instead, today’s tax code turns that principle on its head by letting the wealthiest of the wealthy pay virtually nothing on their gains. Not only are top tax rates on ordinary income low by historical standards, the uber-wealthy also stockpile increasing amounts of capital income while paying little or no tax on those accretions of wealth. The resulting negative feedback loop—whereby the rich use their wealth to influence the U.S. political system to skew policy in their favor, including giving themselves even more tax cuts—undermines democracy. In many cases, this allows economic elites to get what they want, even if a majority of citizens disagree.2 The TCJA is a prime example of this problem. The bill passed into law despite overwhelming public opposition to tax cuts for the wealthy,3 and some lawmakers admitted that the motivation behind the bill was to satisfy political donors.4

Reversing this troubling trend will require a higher top tax rate for those with extremely high incomes as well as a better way of incorporating wealth and the income it generates into the determination of how much tax a person owes. Accurately accounting for wealth is key to establishing a fair tax system. Policymakers have many options when it comes to taxing wealth or taking wealth into account, including implementing innovative approaches to the tax system and revamping existing provisions of the tax code. Well-designed adjustments to account for the current composition of income and wealth at the top could slow the ballooning imbalance in the structure of the U.S. tax system. Moreover, making these adjustments could lead to a more inclusive economy in the long run, especially if the revenues are invested in areas such as education, infrastructure, and scientific research.

Finally, as policymakers consider ways to better account for income and wealth inequality in the U.S. tax code, they should beware of myths surrounding taxation of the wealthy that may be used to push back against new proposals. This report challenges these misleading and commonly cited claims made by opponents of rebalancing the tax code and putting the economy on a better track.

Failing to adequately tax extreme wealth contributes to economic inequality

Over the past several decades in the United States, the very wealthy have experienced disproportionately large income growth compared to everyone else. That income comes in part from wages and salaries, but an increasingly large share of income among the wealthy derives from the assets they own. Those assets, minus any debts owed, represent the net worth or wealth of an individual—and the ultrarich now hold an astounding share of all U.S. wealth.

Disparities in wages and salaries are huge. By one estimate, the typical CEO in 2017 made 347 times the salary of the average American worker compared to 20 times as much 50 years ago.5 The wages of the average American worker used to keep pace with the growth of the U.S. economy, but in recent decades, workers’ wages have stagnated in real terms.6

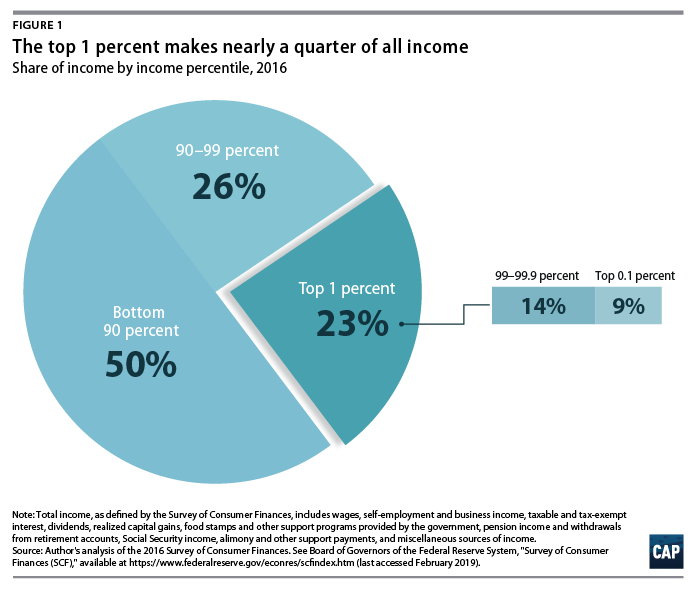

When other sources of income are counted, such as self-employment and business income, capital gains, interest income, and income from government programs, nearly one-quarter of U.S. income goes to the top 1 percent of income earners, while a mere 14 percent goes to the bottom half of income earners. (see Figure 1)

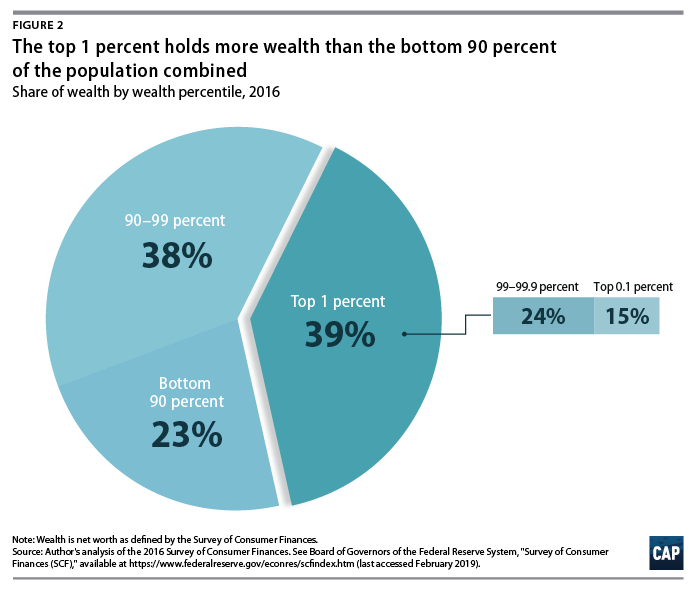

Disparities in income, however, are dwarfed by disparities in wealth—the assets an individual owns minus the debts they owe. Wealth encompasses everything of significant value that a person owns, including real estate, corporate stock, or ownership interests in a noncorporate business such as a partnership, S corporation, or limited liability corporation (LLC). Most of the assets the wealthy hold today are financial assets, which are nonphysical assets that often can be easily converted to cash. In 2016, 80.4 percent of the wealth of the top 1 percent consisted of financial assets such as corporate stock, financial securities, mutual funds, interests in personal trusts, and ownership interests in unincorporated businesses.7 The value of financial assets has grown significantly over time.

Wealth disparities are greater in the United States than in any other country in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).8 In the United States, the top 1 percent holds more wealth than the bottom 90 percent of the population. (see Figure 2)

This inequity is even more stark among the uber-wealthy, or the top 0.1 percent and the top 0.01 percent. The incomes and wealth of this ultra-rich demographic have reached unprecedented levels.9 Meanwhile, middle-class wealth is growing much more slowly than wealth at the top and still has not recovered the losses from the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession.10 Close to half of all American households have less wealth today in real terms than the median household had in 1970.11 Wealth inequality has also worsened along racial and ethnic lines since the Great Recession. By 2014, the median net worth of a white household was $141,900—thirteen times the median net worth of a black household of only $11,000.12

Structural changes in the tax code favoring the wealthy occurred over the same period of time that income and wealth inequality grew. In the late 1980s, the top marginal income tax rate dropped well below 50 percent and today stands at 37 percent.13 That means that a lawyer who makes $650,000 pays the same top tax marginal tax rate as a CEO who makes an annual salary of $10 million.14 This was not always the case. Since the enactment of the income tax in 1913, the U.S. top marginal income tax rate has typically been 50 percent or higher.15 In fact, for more than four decades, the top tax rate was 70 percent or higher.

In the past few decades, payroll taxes on wages and salaries to fund Social Security and Medicare also increased significantly, with the combined rate rising from 11.7 percent in 1975 to 15.3 percent today. The larger Social Security portion of payroll taxes applies only on earnings below a certain threshold, currently $132,900.

This failing of the tax code with respect to wages and salaries, as well as income from certain assets that are also subject to ordinary tax rates such as interest on certain bonds or a bank account, is straightforward and easy to understand—the rates are simply too low for those who make the most. However, the failings of the tax system with respect to wealth and much of the income it generates are more complicated and extensive. They are the primary reason why the tax system favors the wealthy. Like the reduction in top rates on salaries, the weakening of taxes on wealth and wealth-related income has also occurred over the past few decades, most recently through the TCJA.

How the structure of the tax system heavily favors those with great wealth

The enormous amount of wealth held by the top 1 percent yields a variety of types of income, most of which are given special treatment in the U.S. tax system. The tax system favors both the income produced by wealth assets and the assets themselves, which normally increase in value.

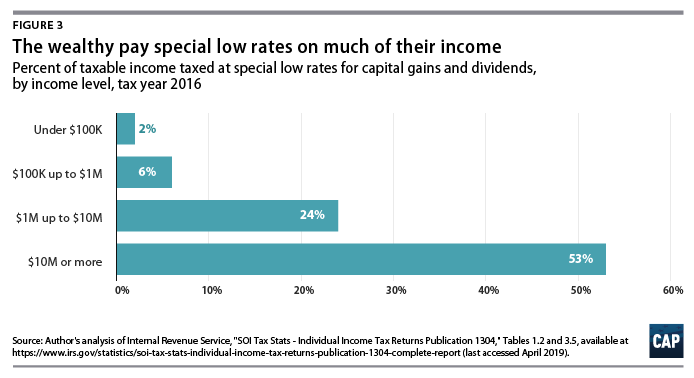

Capital income includes dividends, capital gains from the sale of assets, interest on bonds and other financial assets, and profits from businesses a person owns. Because the very wealthy hold most of the financial assets in the United States, capital income represents a much greater share of their total income, and much of that capital income is taxed at special low rates. (see Figure 3)

Capital income also includes economic rents, which are the payments an owner receives from an asset that exceed what is deemed economically or socially necessary—in other words, returns beyond what is considered normal in a competitive market.16 Economic rents usually exist when one person or company is the sole owner of the asset, or when there is no competition in the market for that asset.17 Experts cite a number of factors contributing to the extraordinary growth in economic rents in recent decades. These include increased concentration in industries18 such as technology and finance and the proliferation of patents and copyrights in industries such as pharmaceutical drugs and entertainment—both of which confer monopoly-like benefits.19 Rents have enabled a small group of the wealthy to capture a very large share of profits on certain assets, which helps to explain the skyrocketing wealth among the top 0.1 and 0.01 percent.

In addition to rents, capital income may include labor income that is disguised as capital income. One well-known example is the practice of private equity fund managers taking a portion of their compensation out of their fund’s profits. This carried interest makes this portion of their fees appear to be capital income, which is taxed at a much lower rate than wage and salary income.

Large income disparities today are all the more concerning because they indicate that the wealth gap is likely to keep growing. Individuals with high capital incomes save increasing amounts and acquire more assets, while those with less capital income fall further behind.

For the wealthy, the tax system’s treatment of capital assets and the income they generate is a gift that keeps on giving. While some capital income is taxed as ordinary income, most capital assets and capital income receive favorable treatment under the U.S. tax code compared to the treatment of wages and salaries. The result is a tax code that is heavily tilted toward the wealthy, who own the majority of high-value capital assets.20

Over the past few decades, legislative changes, most recently in TCJA, have weakened taxation of capital income, even as the stockpile of capital assets held by the wealthy has grown dramatically—in part because this wealth is compounded by lower-taxed income from those assets. Together, these changes mean that the tax code has played a significant role in helping the rich get richer by enabling them to avoid some or all taxes related to their ownership of capital assets and amass ever-larger amounts of wealth—more than they would have if the tax code were more equitable.

Here are just some of the ways in which the U.S. tax code favors wealth and the income it generates:

- Lower tax rate on capital gains and dividend income

In any given year, the wealthy may receive income from their capital assets, such as gains from the sale of a capital asset or dividends on stock. This capital income is subject to a much lower tax rate of 20 percent.21 The wealthy are best positioned to take advantage of this favorable rate. According to the Tax Policy Center, the top 1 percent of households with incomes greater than $750,000 in 2018 reported nearly 69 percent of all capital gain on tax returns and 46 percent of all qualified dividend income.22 Some capital income—such as interest on a bank account or bond, annuity income and royalty income, as well as short-term capital gain, or assets held for less than a year—is treated as ordinary income and thus is subject to the same ordinary income tax rates as wages and salaries. The top tax rate on ordinary income is currently 37 percent.

- New lower tax rate on pass-through business income

Over the past few decades, there has been a sharp increase in income from so-called pass-through businesses.23 Pass-through businesses, such as partnerships, S corporations, and LLCs, do not pay the corporate income tax. Instead, all of their income is passed through to the individual owners, shareholders, or partners to be taxed at their individual tax rates.

Changes in federal tax rates, combined with laws passed at the state level in the 1980s and 1990s, made it more favorable for many businesses to operate as pass-throughs rather than as corporations. These businesses could retain limited liability without having to pay the corporate tax, and average effective tax rates for income from pass-through businesses were significantly lower than the combined effective tax rate on corporate profits that were distributed to shareholders in the form of capital gains and dividends.24

In recent decades, the number of pass-through businesses has increased dramatically. Income from these businesses has grown as a share of total business income, surpassing income from regular corporations that pay the corporate income tax.

Incredibly, while pass-through business income on average was already taxed at a lower effective tax rate than corporate income before the TCJA was passed, the 2017 law established a new, significant loophole for many pass-throughs—a 20 percent deduction for certain pass-through business income.25 Proponents of the deduction claimed that it would benefit small businesses, but they obscured the much greater benefit to large businesses and the wealthiest individuals.26 Subsequent regulations interpreting the new deduction made it even more regressive.27 A recent analysis by the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on Taxation confirmed the tilt toward larger businesses. It found that, in 2018, only 4.9 percent of individuals with eligible pass-through business taxable incomes were high-income taxpayers, defined as individuals with business incomes of at least $315,000 for joint returns. Yet, these higher-income business owners claimed 66 percent of the total benefit from the deduction.28 In fact, the new pass-through deduction combined with the TCJA’s new business-expensing provisions and corporate tax rate cut delivered much larger benefits to big businesses than to small businesses.29

- No tax on unrealized gain, or deferral

Perhaps the greatest tax advantage of owning capital assets is that the gain in value of those assets is generally not taxed at all, so long as the assets are not sold. This untaxed increase in value is called unrealized gain, and the ability to avoid paying tax until the asset is sold or transferred to another person or entity is referred to as deferral. The wealthy have so much income and wealth that many can afford to hold on to capital assets indefinitely, thereby shielding them from taxation as their assets grow in value. How much income they realize is largely in their control, such as deciding when or whether to sell their assets. Until they do, the gains are unrealized and therefore untaxed. Moreover, the wealthy can strategically sell some assets at a loss in order to offset the gains that they do realize on other assets.

The gain on capital assets can be substantial over time. For example, corporate stock, a type of capital asset, soars in value when the stock market goes up—and the market has hit record highs in recent years.30 Corporate stock may also increase in value as a result of corporate tax cuts, such as those enacted in the TCJA.31 A huge tax cut for corporations represents a windfall for past investments made by those firms, increasing the value of the company’s stock.

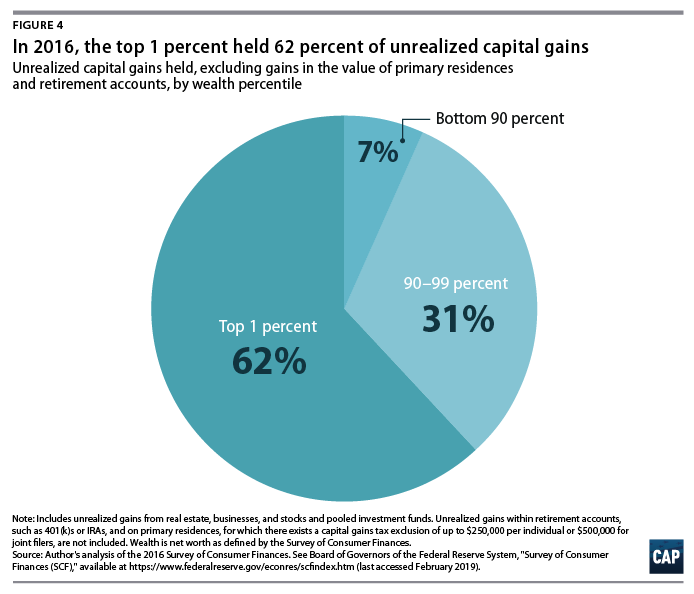

While precise estimates are not currently available, the evidence above suggests that unrealized, and thus untaxed, gain on capital assets represents a significant portion of wealth at the top. Gains on primary residences and retirement accounts are tax favored, as policymakers consider these assets foundational to middle-class wealth. However, as shown in Figure 4, even if gains on these assets are excluded, the majority of unrealized capital gains are held by the top one percent.

Even though assets generally must be held in order to defer tax on the gain, the wealthy can still derive substantial benefits from the assets they hold. One way is to simply borrow against the assets because amounts borrowed are not considered income for tax purposes. Professor Edward McCaffery refers to this borrowing against capital assets as the monetization of unrealized appreciation and cites as an example the $10 billion line of credit secured by Oracle CEO Larry Ellison in 2014.32 Merely owning valuable capital assets may enable a wealthy person to obtain loans at very low interest rates since creditors know that wealthy borrowers can liquidate assets if needed. The wealthy can enjoy use of the loaned funds while keeping their assets. Under some circumstances, they may even be able to deduct the interest on the loan, thereby lowering their taxes on other income. When a wealthy debtholder dies, assets can be sold immediately by the heirs, who will owe no income tax on the unrealized appreciation due to the stepped-up basis rule described below. They can use the proceeds to pay off the debt, keeping what is left tax free.33

Wealthy taxpayers also can avoid tax on the unrealized gain on their assets by donating the assets to charity. This results in a double tax benefit: The wealthy donor never pays tax on the gain and can claim a charitable deduction based on the full market value of the assets at the time of donation.34

- Stepped-up basis

Normally, gain in the value of an asset is taxed when the owner sells or transfers the asset. However, if a person transfers an asset through a gift or bequest, no income tax is triggered. If a person holds an asset until they die, neither the individual nor their estate will ever pay income tax on the gain that accrued during the individual’s lifetime, though some estate tax may apply, as discussed below. In addition, because of a provision in the tax code called stepped-up basis, individuals who inherit the assets do not have to pay income tax on that gain either—only on gain that accrues after they inherit the asset.35

Suppose, for example, a parent bought stock for $1 million. The $1 million—what the parent paid—is called their basis in the stock. Now, suppose they held it until they died, at which point it was worth $3 million. The parent’s estate would not pay income tax on the $2 million gain. Yet, had the parent sold the stock during their lifetime after its value increased to $3 million, the parent would have had to pay income tax on the $2 million gain.

Their heir or heirs would not pay income tax on that $2 million gain because heirs only pay income tax on gain occurring after the date of inheritance—and then only if and when they sell the asset. If the heir sells the asset immediately after inheriting it, they would pay no tax because when the asset is bequeathed, the basis is stepped up to its stock market value at the time of the parent’s death—in this case, $3 million. In other words, the heir inherits the asset with a basis of $3 million. Under 2019 tax rates, the income tax savings for the wealthy heir on the $2 million of unrealized gain could be as much as $430,970.36

- Decimated estate tax

The modern estate tax, which is essentially a one-time tax imposed when wealth is transferred at death, was intended in part to break up large concentrations of wealth.37 Over time, however, the estate tax has been significantly weakened, and there are many loopholes in the tax system that enable the wealthy to bypass the estate tax altogether. The TCJA further weakened the estate tax, which now only applies to estates worth more than $22.8 million per couple, or $11.4 million for singles, meaning that the tax only applies to the portion of the estate value that exceeds the threshold.38 In 2018, the Tax Policy Center estimated that, of the 2.7 million Americans who would die in 2018, only about 0.07 percent, or 1 in 1,400 people, would pay any estate tax.39

Table 1 in the Appendix summarizes the disparate tax treatment of different forms of income and wealth. It shows how the tax code does a thorough job of taxing wages and salaries but weakens substantially as it moves from short-term capital income, to long-term capital gains and dividends, to unrealized gain on assets a person owns, to overall wealth.

The TCJA demonstrated that corruption is exacerbating the tax system’s structural failings

In 2017, the economy was growing, and corporate profits and wealth at the top were soaring. Yet, tax revenues were low. Congress had cut taxes numerous times over the preceding two decades, and federal revenues were falling further behind federal spending, even though discretionary spending had been subject to tight limits.40 In addition, mainstream economists pointed out the coming costs of an aging population.41 They urged against tax cuts and in favor of making long-overdue investments in education and improvements to crumbling infrastructure—all measures that would make the economy healthier and more equitable in the long term.42

Instead, in a display of unprecedented partisanship and dysfunctional lawmaking, Congress rushed through changes to the tax code that ran completely counter to the preferences of the American people.43 There were no public hearings allowing affected taxpayers to express their views on the proposed changes.44 The congressional majority, drafting the legislation on a strictly partisan basis behind closed doors, openly admitted the pressure from their wealthy donors to pass favorable tax changes and their fear that failure to do so would mean no additional campaign funds.45

The tax cuts that emerged from this tortured process and were signed into law by President Donald Trump will enable the wealthy to further enrich themselves and their families, including by gaming the tax code even more than they have in the past. The TCJA is already expanding the class of well-heeled tax advisers who have a vested interest in seeing tax cuts continue unfettered.46 The returns on investment for those who participate in this corrupt feedback loop are immediate and substantial, even as hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars in tax revenue are lost. This dysfunctional tax policymaking process and the ways in which the ultrawealthy unduly influence legislation pose a serious threat to U.S. democracy.

The major provisions of the tax law that benefited the wealthy included a reduction in the top individual income tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, a new 20 percent deduction for many forms of pass-through business income, and a large increase in the exemption from the individual alternative minimum tax. In addition, the TCJA dramatically weakened the estate tax and cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent—a boon to the wealthy who own the majority of stock.

The Tax Policy Center estimated that the new law increased after-tax incomes for people with incomes of more than $1 million by 3.3 percent, compared to only 1.3 percent or less for people earning less than $100,000.47 In dollar terms, the disparity appears even more stark: Millionaires received an average tax cut of $69,840, while people making less than $100,000 received a tax cut averaging only $453. Moreover, if lawmakers respond to the huge cost of the tax cuts by cutting spending on Medicare, Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, or other programs, middle- and low-income taxpayers could be disproportionately affected and find themselves worse off than if there had been no tax cuts at all.48

The many new loopholes and tax cuts in the TCJA are a windfall to the wealthy and corporations. However, as egregious as they are, they represent just one layer of icing on what was already a very rich cake. The fundamental failing of the current tax system—the fact that it is tilted in favor of the wealthy—long predated the TCJA. The assets held by those at the top have been accumulating for decades, and merely increasing tax rates on the future realized income from those assets will do little to slow the rate at which those assets are likely to grow. Eliminating, reducing, or offsetting the wide array of tax advantages for those who hold the largest amount of capital assets is an important first step toward restoring balance in the U.S. tax system and addressing income and wealth inequality.

There are many ways to tax extreme wealth, including a wealth tax

There are several options to better tax extreme wealth. One approach would be to tax net worth above a very high threshold on an annual basis. Lawmakers considering this innovative tax should analyze a number of options and design possibilities. In addition to this direct approach of a tax on net worth, there are many ways to better incorporate wealth into the existing tax system to ensure that extreme wealth does not slip through the cracks.

A wealth tax

A tax on extreme wealth would address concerns about wealth inequality in a straightforward manner and recognize that individuals’ ability to pay tax is a function of both their income and their wealth.

Under this type of tax, wealthy individuals would assess the total value of all of their assets at the end of the year and subtract any debts they owe to arrive at their net worth or wealth. A small tax would then be imposed on their net worth. Drawing from examples in other countries and proposals advanced by tax experts in the United States, other features should include:

- Comprehensive base: The base in a wealth tax—the amount on which the tax is applied—is an individual’s net worth or wealth. Ideally, no assets should be excluded from the tax. This broader base would increase the revenue raised by the tax. Countries where wealth taxes did not work out well in part struggled with exemptions for specific types of assets.49 Exempting assets both adds to administrative complexity and encourages wealthy taxpayers to shift the composition of their assets in order to avoid tax. The need for specific asset exemptions is greatly diminished if there is a very high uniform exemption amount, so that the tax only applies to the very wealthy.

- Uniform exemption: A direct tax on wealth typically is applied only to the amount of an individual’s wealth that exceeds a uniform exemption amount or threshold. The higher the exemption amount, the fewer families that will be affected by the tax. Under a proposal advanced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), for example, only families with wealth exceeding $50 million would be affected by the tax. According to economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, at this exemption amount, the top 1 percent of income earners would pay 97 percent of the tax.50

- Low and progressive rates: Tax experts recommend a relatively low tax rate if the wealth tax will be imposed on an annual basis. This rate would keep growth at the very top in check, and it would also take back a small portion of the untaxed gain accrued over previous years. Proposed annual rates for wealth taxes have varied but are usually very low.51 Some proposals appropriately call for progressive rates, or higher marginal tax rates for the most extreme levels of wealth.52

As with all taxes, there are challenges to administering a wealth tax. Opponents claim that the tax would be unconstitutional, though the counterarguments for that claim are robust, as discussed later in this report. Two administrative challenges to a wealth tax relate to valuation and tax avoidance.

- Valuation: A wealth tax requires adding up the total value of an individual’s assets before subtracting the cost of any debts the individual owes. For publicly traded assets, such as stock, valuation is relatively easy. However, ownership interests in a nonpublicly traded business and other hard-to-value assets can present greater challenges.

While this is perhaps the single biggest challenge of administering a wealth tax, it is not necessarily as difficult as detractors claim. Moreover, administrative mechanisms and proxies can be developed for valuing assets. Under provisions in the current tax code, tax administrators and accountants already have experience with the process of totaling assets and valuing them for purposes of the estate and gift tax and for charitable contributions.53 Most U.S. localities also impose real and personal property taxes, which require valuation. Finally, some argue that the value of certain types of assets change frequently, an issue that can be addressed by averaging. In any event, fluctuation in value of assets should not be a reason to abandon a wealth tax altogether.

In our digital world, where there is greater information-sharing between the tax authorities of different countries, locating and monitoring the value of assets seems to be less of a problem than it once was.

- Tax avoidance and evasion: Another potential challenge of imposing a tax on net worth is that the very wealthy may attempt to evade the tax by shifting assets offshore or avoid the tax by shifting the composition of their assets toward assets that are more difficult to value. These problems are not new, and there are many strategies already developed by tax policymakers and administrators to address these issues in other areas, including the estate tax.54 An analysis of the wealth tax in Switzerland also suggests that the avoidance problem may be exaggerated.55

All taxes have administrative challenges that must be weighed against the potential benefits, which may be significant under a wealth tax. A wealth tax would gradually tax a portion of the wealth that has accumulated over the past several decades as the structural failings of the tax code enabled extreme wealth accumulation, while also placing a check on the accumulation of even larger fortunes going forward. In addition, it would improve fairness between extremely wealthy individuals who receive little, if any, wage, salary, or other income that is taxed as ordinary income and regular wage or salary earners who have little, if any, wealth and who also pay a substantial amount of payroll tax. And, to the extent that the revenues from a wealth tax are used to improve opportunities for others through public investments such as in education, health care, child care and paid leave, the tax would help make the prosperous U.S. economy more inclusive. Finally, a wealth tax recognizes that the wealthy have benefited either directly or indirectly from a wide range of government goods and services.

A wealth tax would rebalance the tax code toward a more coherent concept of ability to pay and would gradually address the enormous amounts of untaxed wealth accumulated—especially by the top 0.1 percent—over the past few decades from tax cuts and the soaring after-tax profits of corporations and large pass-through businesses.

Other options for increasing taxes on the very wealthy

While a comprehensive wealth tax is a direct way to rebalance the U.S. tax system and begin to remove the strong bias in favor of the wealthy, there are other options for increasing taxes on excessive ownership of capital assets and the income they generate. Like a wealth tax, these approaches would help restore the principle of ability to pay. Some of the options that follow could, and in some cases should, be accomplished simultaneously; they are not necessarily substitutes for each other or for a wealth tax, though policymakers should consider potential interactions of these proposals with each other and with existing provisions of the tax code.

Mark-to-market taxation of unrealized capital gains

Because the wealth tax above is imposed on a person’s net worth, it falls on the full value of a wealthy individual’s assets minus any debts they owe—not just on the increases in value that have accrued on the assets while the person has owned them. Still, since a substantial portion of wealth at the top consists of unrealized gains, taxing them annually would go a long way toward balancing the tax code. That is because the ability to defer paying taxes on the unrealized gain is one way that the wealthy increase their wealth, even as wage earners who hold few, if any, capital assets see most of their income taxes withheld from their paychecks.56

Under this approach, tax would be paid each year on any unrealized gain that occurred during the previous year. The owner’s basis in the asset—what they paid, plus any taxes already paid on gains in earlier years—is subtracted from the value of the asset at the end of the year, with the net gain included in income to be taxed that year, preferably at ordinary tax rates. Tax policy experts refer to this option as mark-to-market taxation of capital assets because it functions as if all capital assets were sold, with any gains taxed, and repurchased at the market price at the end of the year, with the taxpayer’s new basis marked to the market price at the end of the year.57 As with a wealth tax, publicly traded assets are more easily taxed under this approach since there is a readily ascertainable market price. However, non-publicly traded assets, such as private businesses, are harder to value. Proponents of mark-to-market taxation have developed various suggestions for how to handle assets that are more difficult to value. Typically, they suggest not taxing the assets annually, but instead imposing an extra charge at the time of realization that takes away the benefit of deferring the tax. Upon sale, the taxpayer would pay both income tax on the gain—that is, the value that exceeds the basis—plus an extra charge representing the time value of the benefit of avoiding tax until realization.58

Eliminate stepped-up basis and tax unrealized gains before transferring assets to heirs

When a person dies, a final income tax return must be filed on the decedent’s behalf. However, as mentioned above, this tax return does not have to include the unrealized, untaxed gain on any assets held at death. Heirs who inherit those assets do not have to pay tax on that gain either—they take as their basis in the asset the market value at the time they receive it. Regardless of any other proposals that are adopted to rebalance the taxation of work and wealth, lawmakers should repeal the stepped-up basis rule and require that unrealized capital gains be included in the final income tax return of the deceased.

Tax inheritances the same as paychecks and close trust loopholes

The current federal estate tax is effectively a wealth tax. However, the estate tax is only imposed once in an individual’s lifetime and has been eroded to the point where it only applies to the value of an estate exceeding $11.2 million per person, or $22.4 million per couple.59 Only 0.07 percent, or 1 in 1,400 estates, will be affected by the estate tax for 2018. One option to address this problem is to reinvigorate the estate tax by lowering the exemption amount and increasing the tax rate. This would ensure that a larger amount of previously untaxed wealth is taxed before it is transferred to heirs.

Alternatively, New York University law professor Lily Batchelder has proposed replacing the current estate tax with an inheritance tax.60 The current estate tax already effectively falls on heirs because the tax presumably reduces what they might otherwise inherit. An inheritance tax would expressly recognize this dynamic and impose the tax on each heir who inherits assets, rather than on the estate of the decedent. Inheritances would therefore be viewed as income to the heir and taxed accordingly. Gifts could also be subject to tax, with an overall lifetime exemption amount applying to the total value of all gifts and inheritances received. For example, all individuals could have a lifetime exemption of $2 million; in this case, the inheritance tax would begin to apply when the total value of any gifts or inheritances they receive over their lifetime exceeds this amount.

There are many benefits to a unified gift and inheritance tax. Perhaps most importantly, it represents a more accurate way to measure a person’s ability to pay. Under current law, a person who inherits $50 million but makes an annual salary of $100,000 pays the same amount of tax as a person who makes the same annual salary but inherits nothing. Less than 1 percent of heirs in a given year inherit more than $1 million, so an exemption amount of $1 million or more would only affect a relatively small number of lucky heirs.61 An inheritance tax would also encourage the wealthy to spread their wealth among heirs or other recipients of bequests, such as charities.

Under either of these options, it is also important to close loopholes in the tax code that currently enable the very wealthy to transfer ownership of wealth assets to heirs without paying tax. Former President Barack Obama and others have identified and proposed fixes to various types of trusts and other mechanisms allowing this type of tax avoidance.62

Tax capital gains and dividends as ordinary income

One clear way to rebalance the tax system between wages and wealth would be to increase the tax on capital gains and dividends, which currently are subject to a tax rate of 20 percent—significantly lower than the top marginal rate of 37 percent on ordinary income. A higher tax rate on capital gains might encourage the wealthy to hold on to their assets for longer, so increasing the tax rate on capital gains should be combined either with the mark-to-market system of taxing unrealized capital gains on an annual basis, or with repeal of the stepped-up basis rule mentioned above. Unlike a wealth tax, a mark-to-market regime, or the estate tax, an increase in the tax rate on capital gains does not reach unrealized, untaxed gain. However, a higher rate on realized gains would equalize the treatment of income from work and income from selling assets and thus reduce the ability of the very wealthy to amass even more wealth.

Increase IRS enforcement funding and take other steps to close the tax gap

Funding for the IRS has decreased significantly over the past several years, and this has hampered the agency’s efforts to obtain uncollected taxes from very wealthy individuals. As mentioned above, it is far less costly for the IRS to collect taxes from lower-income taxpayers. With simpler returns, a letter from the IRS known as a “correspondence audit” often can elicit compliance from the taxpayer without any further effort or expense on the part of the agency.

While ensuring that higher income taxpayers are paying what they owe can be complex and time-consuming, the return on investment may be much greater. The biggest challenge is that Congress has failed to provide the resources the IRS needs to hire employees with the expertise to audit high-end tax returns—indeed, the IRS has approximately the same number of auditors today as it did in the 1950s, when the economy was a fraction of the size it is today.63 Increased IRS funding could be used to hire additional auditors, increase audit rates for wealthy taxpayers, and establish a minimum audit rate.

Compliance improves when third parties are required to report income information to the IRS, such as when an employer sends the IRS a 1099 tax form confirming the income it has provided to an employee. Form 1099 is required from third parties for a wide variety of types of income, including payments to an attorney, prizes and awards, medical and health care payments, and more. However, very little information reporting is required for capital income. Lawmakers should establish additional information reporting by third parties on capital income to help close the gap in tax collections among wealthy taxpayers. These enforcement measures would reduce tax avoidance by high-income taxpayers under current law and would provide an important complement to any of the measures proposed above.

Myths about the taxation of wealth

An individual’s wealth clearly affects his or her ability to pay taxes. Critics who oppose taking wealth into account for tax purposes tend to resort to an array of dubious arguments and outright falsehoods to push back against measures to rebalance the tax code.

Myth #1: Taxing wealth is clearly unconstitutional

Critics of a wealth tax claim that it is unconstitutional under Article I, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution, which states that representatives and “direct taxes” must be apportioned among the states according to their population. A tax on wealth cannot be apportioned according to population without applying a different tax rate in each state—an absurd proposal—because states differ in terms of how many wealthy citizens live there and the size of their wealth. Thus, the question is whether a wealth tax is a direct tax subject to this clause of the Constitution.

There is robust debate on the constitutionality of a wealth tax, but the case for constitutionality is strong and should even appeal to the current conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court, given the narrow interpretation of direct taxes adopted shortly after ratification of the Constitution.

In Article I, Section 8, the framers of the Constitution expressly granted broad taxation powers to Congress for the purpose of carrying out its other powers, such as paying federal debts and providing for the common defense and general welfare of the country.

The requirement that direct taxes be apportioned, cited above, is found in a separate clause and was part of a notorious political compromise to deal with the divisive issue of slavery. The full clause reads:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.64

As constitutional law professor Bruce Ackerman summarizes, “[T]he South would get three-fifths of its slaves counted for purposes of representation in the House and the Electoral College, if it was willing to pay an extra three-fifths of taxes that could be reasonably linked to overall population.”65 The only other mention of a direct tax is found in Article I, Section 9, which clarifies, “No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or Enumeration herein before directed to be taken.”66 Professor Ackerman explains that this provision was likely included to ensure that future direct taxes would be apportioned according to the same formula used to determine representation in the U.S. House of Representatives.67 Given the outstanding debt owed by Southern states to the new federal government, both sides had reason to ensure that the rules of taxation and representation were consistent.

In 1796, less than 10 years after ratification of the Constitution, a majority of the Supreme Court—which included four framers who had participated in the development of the Constitution—recognized the political nature of the direct tax clauses and established a rule of reason for interpreting it in the case of Hylton v. United States. Justice Samuel Chase wrote, “The rule of apportionment is only to be adopted in such cases, where it can reasonably apply…”68 The court upheld a carriage tax, finding that it could not reasonably be apportioned fairly among the states and thus was not a direct tax. For the next 100 years, the Supreme Court continued to apply this reasonableness standard to uphold a number of different types of taxes.

This history, along with the abolition of slavery in 1865, should be enough to convince any constitutional originalist of the prudence of not extending the meaning of direct tax beyond the capitation and real estate taxes expressly included in the term up until that time.69 As professor Ackerman argues, if the early justices believed that the direct tax clauses should be narrowly construed while slavery still existed, it makes no sense to expand the clauses after the rest of the bargain with slavery had been repealed.70

Opponents of a wealth tax often rely on the 1895 Supreme Court decision in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company, which used an unprecedented and broad interpretation of “direct tax” to strike down an income tax. The case created a public furor at the time because it expanded the direct tax limitation to strike down the income tax during the Gilded Age—a time of extreme income and wealth inequality. The Pollock case is widely viewed as an aberration. Its core finding that an income tax was unconstitutional was effectively overturned by the 16th Amendment, which allows Congress to impose a tax on income “from whatever source derived.”71 After the Pollock decision, the Supreme Court returned several times to the reasonableness test of Hylton to uphold taxes on inheritances and corporate incomes.72

It is also worth noting that Pollock was decided during a dark period of constitutional history in which the court struck down many democratically adopted economic and social policies, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson decision—which upheld racial segregation on Louisiana trains—and decisions striking down minimum wage requirements, maximum hour protections, and limitations on the use of child labor.73

Although the application of the Pollock decision to an income tax was overridden by the 16th Amendment, the Supreme Court has never overturned the direct tax interpretation specifically as it might apply to a wealth tax. However, in deciding that hypothetical case, it would be difficult for the court to ignore the extreme income and wealth inequality that exists today. A broad interpretation of what constitutes a direct tax would serve only to worsen growing income and wealth inequality by limiting an important tool—the power to tax—conferred by the Constitution on the federal government to provide for the general welfare.74 The logical conclusion of striking down a wealth tax would be the disintegration of the principles on which our democracy was based—that all are equal under the law.75 It is not surprising, then, that many highly respected legal experts have expressly stated that they believe a wealth tax—such as the one recently proposed by Sen. Warren—would be constitutionally permissible.76

Myth #2: A higher top income tax rate is an effective substitute for a wealth tax

Higher top marginal tax rates on the highest labor incomes alone would not affect a great deal of wealth or the gains that wealth generates. To begin with, a very large share of the reported income of the wealthy—namely, capital gains and dividends—is taxed at much lower rates, meaning that the tax code would be more progressive at the top if there were no preference for this type of income. Moreover, because the tax code does not tax gains until assets are sold, a large amount of wealth is not included annually as part of taxable income and may never be subject to income tax at all if held until the owner dies. The tax code would still be tilted heavily in favor of the uber-wealthy if the only change were a higher top tax rate on ordinary income, especially if the tax rate on dividends and realized capital gains remained low.

Myth #3: Taxing wealth would materially harm economic growth

Taxing capital is an essential part of developing a tax system that is fair and based on an individual’s ability to pay. The idea that any taxation of wealth inevitably impedes economic growth is both overly simplistic and challenged by many experts and economists. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz notes, “Rising inequality implies falling aggregate demand, because those at the top of the wealth distribution tend to consume a smaller share of their income than those of more modest means.”77

Taxes to fund the government and improve distribution are not necessarily in conflict with economic growth—in fact, the government is integral to a better performing economy.78 In particular, recent research shows that taxing wealth is unlikely to hinder economic growth when the tax falls on economic rents or if revenues from a wealth tax are used to make social welfare-enhancing public investments, which may have a higher rate of return than private investments.79 Economic rents in recent decades have reached near-historic highs and have significantly contributed to wealth inequality in the United States. Meanwhile, government investments in education and infrastructure can provide a positive rate of return for the economy as a whole; at a minimum, these investments are essential to sustaining a robust economy in the long term.80

In fact, many studies have shown that highly concentrated wealth correlates with poor economic growth over the long term. In times of high concentration of wealth, taxing wealth may improve growth by breaking up unproductive capital, which is then free to be used more productively.81 Some economists cite the United States during the mid-20th century—when economic growth was high despite a more robust estate tax—as an example of this phenomenon.82

Finally, it seems unlikely that a tax on the ultrawealthy would harm innovation, which is a precursor to productivity growth. University of Southern California professor Michael Simkovic refutes the claim that innovation and growth require shifting more wealth and resources into the hands of a small number of billionaires. There is little, if any, overlap between billionaires or half-billionaires and the Nobel Prize,83 and most authors of patents are middle or upper-middle class.84 To reach lucrative commercial success, patented inventions may require substantial business skills related to commercialization and expanding production—skills that patent authors seldom have. On the other hand, those with the requisite business skills depend on the patent author’s innovation.85 Additionally, peer-reviewed studies show that increasing wages increases work effort, while increasing wealth actually reduces work hours.86 In light of these data, it appears that a policy directing revenues from a wealth tax toward public investments in science and education would be more likely to enhance and improve innovation.

Myth #4: Wealth is comprised of previously taxed income, so a wealth tax would constitute double taxation

Critics try to paint wealth as completely comprised of previously taxed income, but this is not the case. As mentioned above, much of the wealth at the top consists of either unrealized gain or other income that has never been taxed. For example, many wealthy people hold a significant number of assets acquired by inheritance. According to professor Lily Batchelder, about 40 percent of all wealth in the United States consists of inheritances, and inheritances represent about 4 percent of annual aggregate household income.87 Notably, lottery and other gambling winnings are fully taxable under the income tax,88 but heirs do not have to pay taxes on their inheritances.

Conclusion

As long as the wealthy can use their money to unduly influence the political system and the structure of the U.S. tax system in their favor, efforts to rebalance the tax code will be difficult to implement. Tax code changes that place a heavier burden on extreme wealth must be accompanied by structural improvements to our political system, including reforms to the campaign finance system, and changes in the legislative process, such as greater transparency around proposed tax code changes and rules to govern conflicts of interest among legislators.

In a world of global markets and digital assets that can be transferred with the click of a button, and where the top 1 percent holds as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, the twin juggernauts of income inequality and wealth inequality are likely to keep growing. Under this scenario, the wealthy will keep seeking additional ways to shield their wealth from taxation, taking the tax code even further from the core principle of ability to pay. Rebalancing the tax code to address this reality will require accounting for the extreme and growing stock of wealth at the top. Only then can we find our way toward an economy that works for everyone.

About the authors

Alexandra Thornton is the senior director of Tax Policy for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Galen Hendricks is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Sara Estep, Research Assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress, as well as the helpful comments of Jacob Leibenluft, Seth Hanlon, Christian Weller, Alan Cohen, Greg Leiserson, and Chye-Ching Huang on earlier drafts. All errors and omissions are solely the authors’ responsibility.

Appendix