“Washington does not have a revenue problem, it has a spending problem.”

This is how the website for the House Committee on the Budget justifies a budget resolution that makes huge cuts to programs for low- and moderate-income Americans—all without asking those at the top to pay even a nickel of additional taxes. Yet looking back at the past several years, federal spending projections already have fallen dramatically, while revenue projections have declined too.

The 2010 report from the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform provides an excellent benchmark to understand how the budget outlook has changed. Informally named the Bowles-Simpson report, the commission’s co-chairs, Erskine Bowles—former chief of staff to President Bill Clinton—and former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-WY), prescribed a mixture of spending cuts and tax increases to avoid a “looming fiscal crisis.”

Lawmakers did not enact the Bowles-Simpson plan—and the plan had serious flaws—but the budget outlook stabilized anyway. At this point, the most urgent spending problem is that lawmakers are cutting key investments, such as affordable housing, scientific research, and public health, to a detrimental degree. But while there is no looming fiscal crisis at this point, the United States still faces long-term budget challenges. As the Bowles-Simpson commission recognized, addressing those challenges requires solving problems on both the spending and revenue sides of the budget. Based on how the budget outlook has changed relative to the Bowles-Simpson plan, spending growth has become a smaller problem, while insufficient revenue has become a larger problem.

How spending fell after Bowles-Simpson

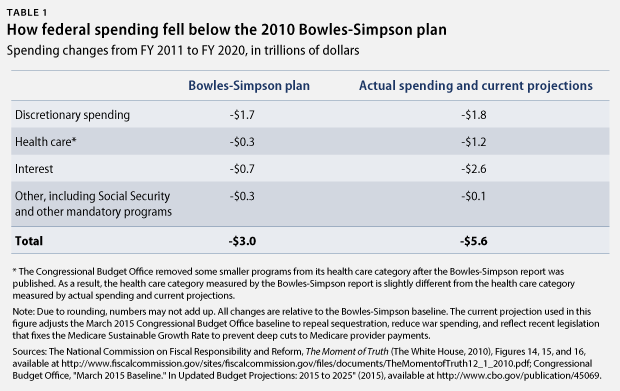

Actual and projected federal spending from fiscal years 2011 to 2020 is now $2.6 trillion less than the levels recommended in the Bowles-Simpson plan. This is especially striking because the Bowles-Simpson commission recommended $3 trillion in spending cuts during this 10-year period, meaning that federal spending is now $5.6 trillion below the starting point, or baseline, in the Bowles-Simpson report.

One spending cut that does not factor into these comparisons is any reduction from sequestration starting in FY 2016, but sequestration cuts from earlier years are included. These cuts have undermined vital public services and damaged the economy, but their worst effects are currently mitigated by a temporary budget deal that expires at the end of FY 2015. The analysis presented in this column increases current spending projections to remove the effects of future sequestration in order to demonstrate that sequestration is completely unnecessary to maintain a stable fiscal outlook.

The enormous reduction in federal spending is mostly attributable to three sources: discretionary spending cuts, unexpectedly low health care costs, and reduced interest payments on the national debt. Changes in discretionary spending are generally due to decisions made by lawmakers, while reductions in health care spending and lower interest payments are mostly driven by economic and technical adjustments to the fiscal outlook since the publication of the Bowles-Simpson report.

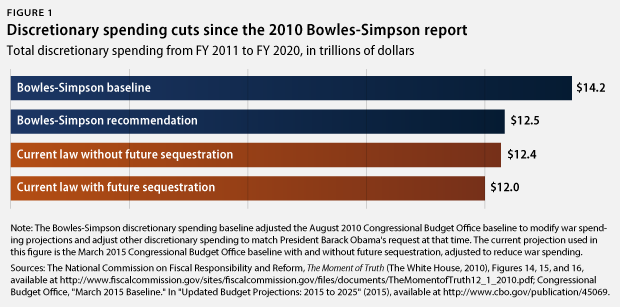

Congress allocates discretionary spending in annual appropriations bills to fund national security, economic investments, public health and safety, veterans’ health care, and other critical government functions. Cuts to discretionary spending began with the appropriations process for FY 2011 and culminated with the Budget Control Act, which was the deal that lawmakers struck in August 2011 to raise the debt ceiling. This legislation established caps on discretionary spending through FY 2021. The Budget Control Act also established a so-called congressional super committee to negotiate additional deficit reduction. When those negotiations failed, the Budget Control Act imposed additional spending cuts via sequestration.

The Bowles-Simpson commission recommended huge discretionary spending cuts: $1.7 trillion from FY 2011 to FY 2020 relative to its baseline. Lawmakers have already exceeded these cuts. Even if sequestration were fully repealed starting in FY 2016, discretionary spending would still be $89 billion less than the Bowles-Simpson plan from FY 2011 to FY 2020.

Federal spending on health care programs has fallen by far more than the Bowles-Simpson plan envisioned because health care costs are growing much more slowly than originally expected in 2010. The Bowles-Simpson commission recommended cutting federal health care programs by $342 billion from FY 2011 to FY 2020. Actual and projected federal spending on Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, is now $1.2 trillion less than projected in 2010. This does not include future automatic sequestration cuts to Medicare, meaning that Congress could repeal sequestration without jeopardizing this progress. While there are many reasons for the recent slowdown in health care cost growth—and while growth rates may not remain low in the future—the cost control policies included in the ACA seem to be showing early signs of success.

Most of the remaining reduction in spending is due to lower interest payments on the national debt. The Bowles-Simpson plan hoped to reduce debt levels enough to save $673 billion in interest payments from FY 2011 to FY 2020. Instead, actual and projected interest payments have fallen by a total of $2.6 trillion during this same time period.

Interest costs have declined because interest rates on the Treasury bonds that finance the national debt are much lower than earlier budget projections assumed they would be. In August 2010, the Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, projected that interest rates on 10-year Treasury notes would be 5.8 percent in 2015. On May 6, 2015, the 10-year Treasury rate was actually 2.25 percent.

How revenues fell after the release of the Bowles-Simpson report

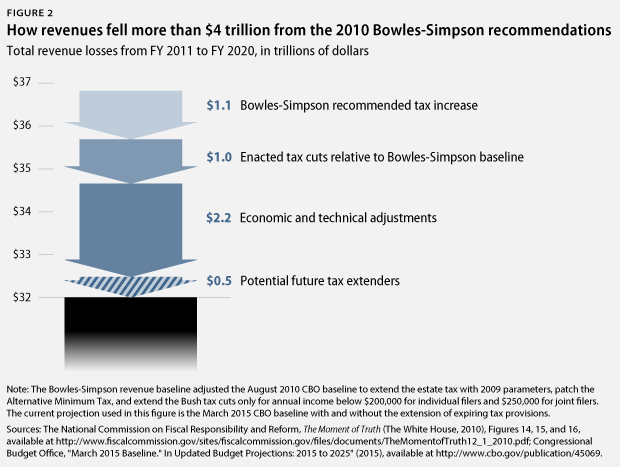

While changes to federal spending projections have dramatically improved the budget outlook, these effects have been partially mitigated by falling revenue projections. Downward revisions to the economic outlook have negatively affected tax revenues by reducing the overall base of income on which taxes are collected. Policy choices to extend tax cuts that were scheduled to expire are also contributing to declining revenue levels, especially compared with the Bowles-Simpson report.

The Bowles-Simpson commission adjusted its baseline to assume that lawmakers would only extend the Bush tax cuts for incomes below $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for joint filers, allowing tax cuts for incomes above those levels to expire at the end of 2010. After the Bowles-Simpson report was published, lawmakers extended all of the Bush tax cuts through 2012 and then extended most of those tax cuts permanently as part of the fiscal cliff deal. The fiscal cliff deal only allowed the Bush tax cuts to expire for single filers and joint filers with incomes above a threshold of $400,000 and $450,000, respectively, while also cutting the estate tax below the Bowles-Simpson baseline.

The Bowles-Simpson baseline also assumed that temporary tax breaks would expire as scheduled, but lawmakers have consistently acted to extend most of these provisions. If lawmakers continue to extend these tax policies—collectively known as tax extenders—tax revenues will be $482 billion lower through FY 2020 than the most recent CBO projection based on current law, under which the tax extenders expire.

The Bowles-Simpson commission recommended raising taxes above its baseline by $1.1 trillion from FY 2011 to FY 2020. Instead, actual and projected revenues are now $3.2 trillion less than the Bowles-Simpson baseline from FY 2011 to FY 2020.

How did this happen? Much of the decline in revenue is due to downward revisions to the economic outlook, but a contributing factor is that lawmakers chose to cut taxes below the starting point used by the Bowles-Simpson commission. Excluding the effects of economic and technical adjustments—which reduced revenue estimates by $2.2 trillion from FY 2011 to FY 2020—lawmakers have cut taxes by $1 trillion relative to the Bowles-Simpson baseline. This tax cut will grow to $1.5 trillion if lawmakers continue to extend all expiring tax provisions.

While the fiscal cliff deal was a tax cut compared with the Bowles-Simpson baseline, the deal did raise $447 billion through FY 2020 compared with permanently extending all of the Bush tax cuts. Even with that interpretation, however, the vast majority of legislated deficit reduction has still come from spending cuts.

Budgeting for the future

Overall reductions in spending and revenues are even greater when examining the next 10 years—FY 2016 to FY 2025—compared with the earlier period of FY 2011 to FY 2020 analyzed in this column. A recent report by Sen. Bernard Sanders (I-VT), the ranking member on the Senate Budget Committee, found that projected outlays from FY 2016 to FY 2025 are now $10.4 trillion lower than projected in August 2010, while projected revenues have declined by $3.5 trillion compared with a baseline where all the Bush tax cuts are permanently extended.

Spending has fallen more than enough to avoid any looming fiscal crisis. Since the vast majority of deficit reduction has come from spending cuts, a balanced approach to reduce the long-term debt requires placing greater emphasis on reasonable policies to increase revenue. Additional revenue also could fund investments to strengthen the economic security of working families via programs such as child care, higher education, and paid family and medical leave while still maintaining a stable fiscal outlook. Rather than continuing economically damaging and fiscally unnecessary sequestration cuts, Congress should instead enact policies to make the tax code more fair and efficient through reforming tax subsidies for investment income, preventing corporate tax avoidance through inversions, and passing other sensible reforms.

Harry Stein is the Director of Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress. Lauren Shapiro is an intern with the Economic Policy team at the Center.

Authors’ note: The Bowles-Simpson baseline was based on the budget outlook published in August 2010 by the CBO, which projected the fiscal consequences of laws on the books at that time. The Bowles-Simpson commission adjusted its baseline to reflect assumptions about future policy changes that the commissioners judged to be more realistic than the CBO baseline. These adjustments patched the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate, or SGR, commonly known as the “doc fix”; modified war spending projections; adjusted discretionary spending to match President Barack Obama’s request at that time; patched the alternative minimum tax; and extended a portion of the Bush tax cuts. The current projections used in this report are based on the March 2015 CBO baseline, adjusted to repeal sequestration, reduce war spending, and reflect recent legislation that permanently fixed the SGR.