In our current health care system, physicians, insurers, and patients must often choose between several treatments without knowing which works better or whether the higher-priced treatment provides added value. Research that evaluates the effectiveness of two or more prevention, diagnosis, or treatment options—known as comparative effectiveness research, or CER—can address this evidence gap. Funding for CER was an important feature of the Affordable Care Act because this research has the potential to lower health care costs over the long term while maintaining or improving the quality of care, according to the independent Congressional Budget Office, or CBO.

The Affordable Care Act created a new independent nonprofit, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, or PCORI, to fund and disseminate CER. Our analysis finds that four years into its 10-year existence, the institute has dedicated less than 40 percent of its research funding to CER. Moreover, PCORI has not initiated a single CER study of medical devices, launched only a few CER studies of drugs, and produced only a handful of analyses that synthesize existing CER studies. Few studies focus on the priority areas identified by the Institute of Medicine, or IOM.

If PCORI is to truly fulfill its mission, the Center for American Progress urges the institute to rapidly scale up its investment in CER to at least 80 percent of its research funding by fiscal year 2016. This investment should focus on studies that:

- Address important gaps in evidence on treatments for common and high-cost conditions

- Can produce actionable results in one to three years

- Synthesize existing CER studies

Time is running out for PCORI to make this necessary course correction. New CER studies can take several years, and the institute’s funding is more than doubling this year before expiring in 2019. PCORI did announce a plan recently to launch a new CER funding initiative in the first quarter of 2014. This plan is highly encouraging, and the institute should build on it to move further in the right direction.

This rebalancing of PCORI’s research priorities will not be easy. CER can threaten the financial interests of powerful stakeholders that profit enormously from marketing new, high-priced products or medical procedures that are marginally or no better than existing alternatives. But that is precisely why PCORI was designed as an independent nonprofit—so it would be immune to undue political and stakeholder influence. To be truly transformative, the institute must finance a bold research agenda and not play it safe.

The importance of comparative effectiveness research

Research on clinical efficacy evaluates whether a single medical intervention works in clinical trials or laboratory studies. Private industry and the National Institutes of Health, or NIH, typically conduct these studies to ensure the safety and efficacy of a new drug, medical device, or surgical intervention. This research, however, does not typically compare the effectiveness of medical interventions, and new drugs and devices are not required to be more effective than existing alternatives to gain Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, approval.

By contrast, research on comparative effectiveness evaluates health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, risks, and benefits of two or more medical interventions—prevention, diagnosis, or treatment options—including drugs, medical devices, medical procedures, and delivery methods. For example, Avastin and Lucentis are two drugs used to prevent blindness in older people. Six randomized clinical trials have found that Avastin is just as effective and safe as Lucentis. But Lucentis is about 40 times more expensive than Avastin, costing Medicare billions of dollars for no added value.

Physicians often practice medicine without knowing the comparative effectiveness of medical interventions. For instance, one of the leading medical textbooks writes that it is not known whether drug treatment works better than removing certain heart cells to treat a common type of heart arrhythmia. While comparative effectiveness research is conducted in other countries, it is less prevalent in the United States.

The purpose of PCORI was to fill this research gap. Section 6301 of the Affordable Care Act, which established the institute, states that its purpose is to advance research and evidence synthesis “with respect to the relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness” of two or more medical interventions and expressly provides “funding of comparative clinical effectiveness research.”

This focus makes sense, since other funding is available for clinical efficacy research through the NIH. In other words, comparative effectiveness research is PCORI’s added value and raison d’etre. Those of us who were involved in drafting the Affordable Care Act believe this interpretation reflects the statute and intent of policymakers.

Research funding priorities and allocation

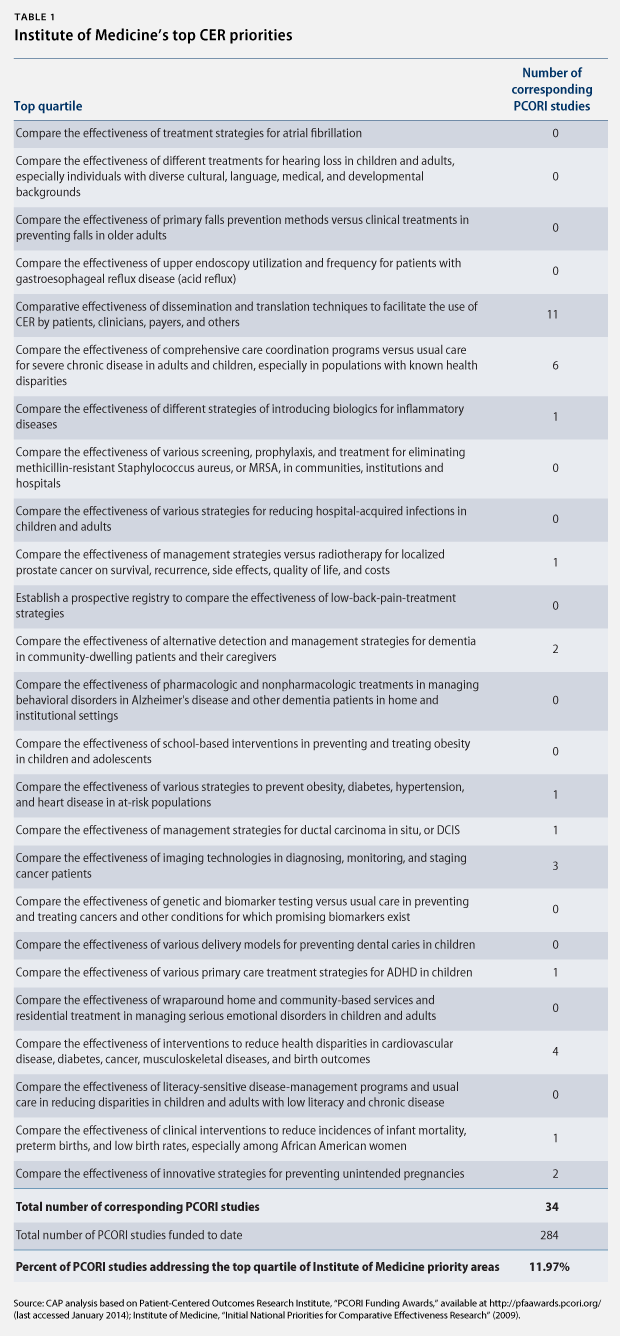

Nine independent and governmental organizations have identified key research areas for CER. For example, the IOM identified 100 initial, specific priority topics in 2009 and ranked them by quartile. (see Table 1)

Section 6301 of the Affordable Care Act also requires PCORI to identify research priorities, taking into account factors such as disease burdens, the potential for improved health, and the effect on national health spending. The institute released its National Priorities for Research and Research Agenda in May 2012. Rather than identifying specific topics for research, however, PCORI identified five broad, cross-cutting areas and funding allocations:

- Assessment of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options (40 percent)

- Improving health care systems (20 percent)

- Communication and dissemination research (10 percent)

- Addressing disparities (10 percent)

- Accelerating patient-centered outcomes research and methodological research (20 percent)

As a result of this prioritization, PCORI is set to spend no more than 40 percent of its research funding on actual CER of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options. But even within this one priority category, the institute has not allocated all of its funding to CER.

According to our analysis of PCORI’s 284 research awards in all categories to date, only 37 percent of its research funding is allocated to studies that compare two or more medical interventions—including studies that compare an intervention to usual care or doing nothing. (see Figure 1) Our results are broadly consistent with an analysis by the California Healthcare Institute.

PCORI does plan to invest more in CER in the near future. The institute recently made a preannouncement of a new funding initiative for large-scale CER studies in real-life settings. The new investment is potentially significant: up to $15 million per project for 12 to 18 projects per year. However, PCORI’s total estimated budget is set to more than double from $320 million in FY 2013 to at least $650 million annually for FY 2014 through FY 2019. Even if the institute finances the maximum of 18 annual awards at the highest level of $15 million while maintaining the current CER allocation for remaining funding, the new investment would increase CER funding to roughly 70 percent of its research funding.

Moreover, we find that 12 percent of PCORI-funded studies address one of the top 25 priority topics identified by the IOM. Of those PCORI studies that do address a top 25 priority topic, we find that the majority only address a single topic: research on dissemination and translation techniques to facilitate the use of CER. Arguably, this topic is not even CER, as it does not compare the effectiveness of medical interventions. In fact, there is no PCORI study on nearly half of the top 25 priority topics. There are no PCORI studies, for instance, comparing the effectiveness of school-based interventions to prevent and treat childhood and adolescent obesity, although childhood obesity is one of the top 25 priority topics and widely acknowledged as a major public health concern.

PCORI’s plan for a new CER funding initiative identified seven priority topics. However, only one of these addresses a top 25 IOM priority topic, and only two of the remaining six address a top 100 IOM priority topic.

Recommendations to fulfill PCORI’s mission

To ensure that PCORI fulfills its mission, the Center for American Progress recommends that the institute do the following:

- Immediately make an investment plan to boost CER funding to at least 80 percent of its total research funding by FY 2016.

- Maximize the number of projects and funding per project under its recent plan for a new CER funding initiative.

- Prioritize CER that addresses the IOM’s top 25 priority topics. While PCORI’s research can be limited by the focus and quality of research applications submitted, the institute can work with contract research organizations and others to conduct studies on selected topics. Furthermore, targeted funding announcements and outreach could contribute to a more focused research agenda.

- Prioritize funding for analyses in the short term that synthesize existing CER studies. For example, a clear synthesis of the studies comparing Avastin and Lucentis might lead private payers and physicians to favor the more cost-effective drug.

- Make available a comprehensive list of all research grants on its website. This information is currently only accessible state by state through an interactive map.

These changes are critical to fulfilling PCORI’s mission and improving the health care system. The institute must make this transition quickly because the private insurers, employers, and enrollees contributing to its budget expect actionable results with good reason. PCORI must urgently scale up investments in CER to maximize its potential to lower health care costs over the long term and improve the quality of care.

Neera Tanden is the President of the Center for American Progress. Zeke Emanuel is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Topher Spiro is the Vice President for Health Policy at the Center. Emily Oshima Lee is a Policy Analyst with the Health Policy team at the Center. Thomas Huelskoetter is the Special Assistant for Health Policy at the Center.