Americans and politicians across the political spectrum have voiced their extraordinarily strong support for immigration reform with a pathway to citizenship. But despite this consensus—and despite the June 2013 Senate passage of an immigration reform plan with a pathway to citizenship—House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) has indicated he will not bring up immigration reform at all this year.

As progress has stalled, immigration advocates have increasingly pressed President Barack Obama to grant a stopgap measure of administrative relief—that is, to enhance prosecutorial discretion, reduce deportations, and grant temporary legal status to some unauthorized immigrants. On June 30, with legislation stalled in the House, President Obama announced that he would use his executive authority by the end of summer to begin to fix the immigration system.

Why the back and forth on immigration reform? After all, most economists agree that repairing the nation’s immigration system will benefit the country’s economy, and that a path to citizenship would improve the fortunes and well-being of a large number of U.S. families. But calculations about policy also hinge on politics, and some conservative pundits have worried that immigration reform will bring a slew of new voters who are less favorable toward a Republican platform. Equally so, a cynic might ask whether administrative relief could be politically helpful to Democrats since immigrants who would directly benefit are not in the country legally and therefore cannot vote.

While House Republicans never produced a piece of legislation, a number of GOP leaders and members indicated they could support a legalization program for unauthorized immigrants, but not a pathway to citizenship. This partly reflects the concerns of some Republican lawmakers that their chances of remaining in office might be threatened by a path to citizenship that eventually grants voting power to the more than 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States.

In the long term, however, it is actually the children of these immigrants who could sway the future of politics in the country. There are approximately 5.5 million children currently living in the United States who have at least one undocumented parent, and an estimated 4.5 million of these children are U.S.-born citizens. Given the minimum 13-year pathway to citizenship envisioned in the Senate bill passed last summer, millions of these young people will turn 18 and become eligible to vote long before their parents. It is these new voters who may reward those who pass immigration reform—or punish those who do not—simply by how they vote.

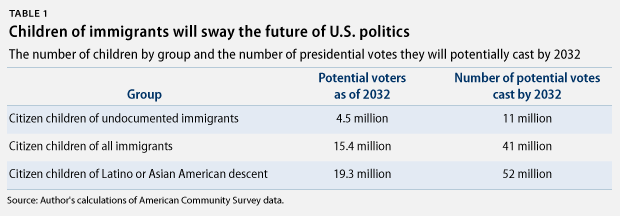

The potential effects are both short and long term. A recent Center for American Progress report by Patrick Oakford, titled “The Latino Electorate by Immigrant Generation,” examined the immediate political implications of not addressing immigration reform as well as the voting patterns of Latinos. This report explores the consequences over multiple presidential electoral cycles, with an analysis focused on the children who might feel the current debate most sharply: the sons and daughters of today’s undocumented residents. We conclude that over the course of the next five presidential elections—by 2032, when all of today’s children of undocumented immigrants will have turned 18—the citizen children of the undocumented will have been able to cast nearly 11 million ballots.

Perhaps this is the 11 million to which political leaders should be paying attention. And yet the effect of today’s divisive immigration politics may be even greater than those numbers suggest, as historical evidence and current polling point to the fact that immigration is a touchstone issue in voting preferences for the children of all immigrants. Widening the lens to include this entire group means a possible 15.4 million voters by 2032, who could potentially cast 41 million ballots over those election cycles. Shifting the focus slightly to consider all citizens of Latino or Asian American descent would bring the total number of new voters to 19.3 million, with a combined potential of 52 million presidential ballots cast. Five presidential cycles from now might seem a long way away, but consider this: President Bill Clinton was re-elected five cycles ago in 1996, and he is still a major figure in U.S. politics today.

Immigration reform may be off the table for 2014, but make no mistake: Failing to enact—or even bring to a vote—immigration reform that includes a pathway to citizenship has significant repercussions and is simply misguided. It fails to recognize the mixed-status realities of many families, eliminates the potential financial benefits to these families and to society at large, and is likely to entrench a second generation against political actors perceived as holding up immigration reform progress. On the other hand, administrative action could provide much-needed relief to immigrant communities and a boost to politicians who support it. Ultimately, this report concludes that the country needs broader change: The immigration system remains broken and Americans want it fixed in a way that respects security, makes way for future immigration, and grants a pathway to citizenship.

Dr. Manuel Pastor is a professor of sociology and American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California, or USC. Justin Scoggins is the data manager at the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at USC. Vanessa Carter is the senior data analyst at the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at USC. Jared Sanchez is a data analyst at the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at USC.