Because of legislated budget cuts enacted over the past two years, spending in a vital but poorly understood category of the federal budget is now on track to decline by the year 2017 to its lowest level on record. This category, known as “non-defense discretionary” spending, is home to an array of programs, benefits, investments, and public protections—the bulk of which enjoy enormous popular support and provide critical services to the nation.

What is in this category of spending with the inelegant and painfully nondescript title that is now projected to dwindle to unprecedented levels? It includes nearly all of the federal government’s investments in primary and secondary education, in transportation infrastructure, and in scientific, technological, and health care research and development. It also includes nearly all of the federal government’s law enforcement resources, as well as essentially all federal efforts to keep our air, water, food, pharmaceuticals, consumer products, workplaces, highways, airports, coasts, and borders safe. It includes veterans’ health care services and some nutritional, housing, and child care assistance to low-income families. It even includes the funding for such national treasures as the Smithsonian Institution, our national parks system, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, better known as NASA.

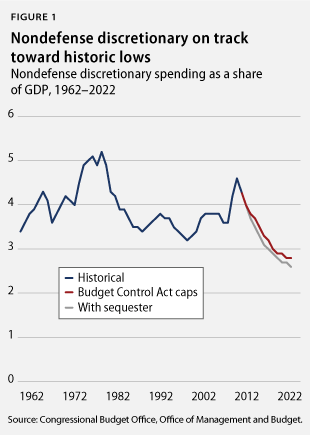

In the past 50 years, federal funding for this broad category of programs and services has never fallen below 3.2 percent of our nation’s gross domestic product—the broadest measure of economic activity. Now, however, because of the spending cuts that have been signed into law since the fall of 2010, within 10 years, nondefense discretionary funding will be about 14 percent lower than its lowest point in the past 50 years—even before taking into account the effects of the large automatic spending cuts scheduled to begin in March 2013.

Since the start of fiscal year 2010, the official Congressional Budget Office projection of nondefense discretionary spending has fallen by more than $730 billion, a cut of more than 10 percent. Those cuts are mainly the result of legislation passed in the intervening months that dramatically curtailed federal spending in this category. Furthermore, if the additional automatic cuts known as the “sequester” remain in place the overall reduction will swell to well over $1 trillion, a 15 percent cut in total.

The very diversity and breadth of the services and programs that live under the banner of nondefense discretionary is what makes the category such a favorite target for budget cuts. The public is far more likely to accept massive cuts to a nameless collection of nebulous programs than it is to a list of specific programs that they know and like. But the effects will be the same nonetheless. We cannot cut these services down to unprecedented levels and expect there to be no impact. This issue brief offers a closer look at what nondefense discretionary spending really is and what the budget cuts will mean.

What exactly is “non-defense discretionary” spending?

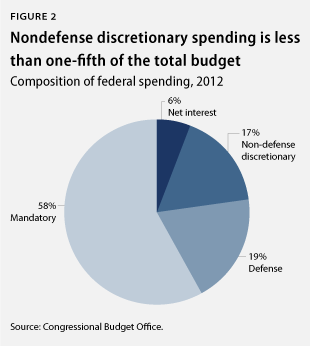

Broadly speaking, there are two types of federal spending—spending that requires an annual appropriation from Congress and spending that does not. The former category is known as “discretionary” spending, while the latter is known as “mandatory.” Mandatory programs such as Social Security or Medicare do not need to go through the annual congressional budget process. Of course, Congress always has the authority and ability to make changes to these sorts of programs if it so chooses, but mandatory spending does not require annual approval. Discretionary programs, on the other hand, must receive new congressionally authorized spending levels each year.

In FY 2012 discretionary spending made up about 36 percent of the total federal budget, about half of which was devoted to the military and other defense purposes. The other half, the nondefense portion, was divided among dozens of different federal agencies to carry out hundreds of different programs.

Unlike the mandatory category of federal spending where a handful of programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the vast bulk of the spending, no single program dominates the discretionary category. In 2012 the single largest nondefense discretionary bureau was the Veterans Health Administration with slightly more than $50 billion in spending, which represented just 8 percent of total nondefense discretionary spending. In fact, the combined spending of the 10 largest discretionary programs still makes up less than half of all nondefense discretionary spending. In 2012 no less than 77 different federal bureaus spent at least $1 billion in nondefense discretionary funding.

Despite this diversity—and notwithstanding the dozens of official budget subfunctions used to classify federal spending—nondefense discretionary spending can be grouped into just seven general categories:

- Economic investments such as highways, schools, and basic scientific research

- Low-income assistance and antipoverty efforts

- Veterans services and benefits

- Law-enforcement efforts and the justice system

- International affairs

- Energy and agricultural investments and environmental protection

- General government operations and miscellaneous activities

Nearly every one of these endeavors enjoys significant public support and serves a broadly accepted public purpose. Put all seven categories together, and overall nondefense discretionary spending totaled about $620 billion in FY 2012, or about 4 percent of GDP. Since 1962 spending on nondefense discretionary programs has ranged from a low of 3.2 percent of GDP to a high of 5.2 percent of GDP. Because of legislation that has been passed over the past two years, however, nondefense discretionary spending is now set to decline to historically low levels.

Impact of the Budget Control Act and the sequester

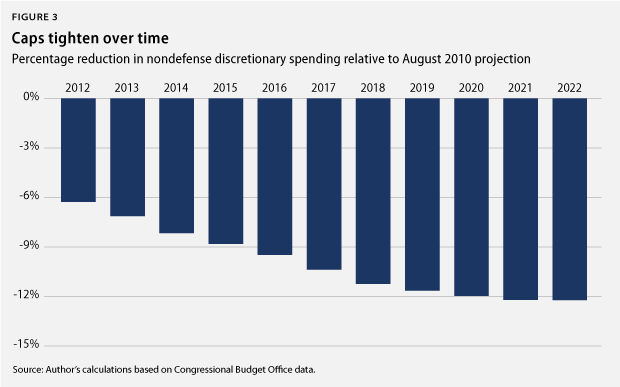

On August 2, 2011, President Barack Obama signed the Budget Control Act into law. That legislation, which resolved a months-long standoff over the debt limit, placed enforceable caps on both defense and nondefense discretionary spending. These caps were set significantly below where spending would have been if the previous fiscal year’s levels had been extended, adjusting only for inflation. One year earlier, using the FY 2010 appropriation levels as a foundation, the Congressional Budget Office projected that nondefense discretionary spending would total almost $7.1 trillion from 2013 through 2022. Under the Budget Control Act, however, nondefense discretionary spending is now projected to be slightly more than $6.3 trillion from 2013 through 2022, according to the most recent Congressional Budget Office outlook. That amounts to a cut of about $740 billion, or more than 10 percent, over the next 10 years.

Though the overall 10-year effect of the spending caps is a cut of about 10 percent, the impact is not uniform in each year. The caps in the initial years are somewhat looser—forcing relatively smaller cuts—but they will grow tighter over time. This fiscal year, for example, spending is expected to be approximately $47 billion lower than the Congressional Budget Office had projected in August 2010, a cut of slightly more than 7 percent. By 2022 the cuts will have grown to $95 billion annually, a 12 percent reduction from the August 2010 projection.

As the caps tighten, nondefense discretionary spending measured as a share of GDP will decline and fall below 3.2 percent by 2017. From 1962 through 2011 nondefense discretionary spending has averaged 3.9 percent of GDP and has never slipped under 3.2 percent. Furthermore, spending will continue to decline in each subsequent year. In 2022, however, nondefense discretionary spending is projected to dip below 2.8 percent of GDP, putting it at more than 30 percent under the past half-century’s average.

In addition to the discretionary spending caps, the Budget Control Act also set up a separate process—known colloquially as the “super committee”—that was designed to produce even more deficit reduction and set up consequences should that process fail. It did fail, and those consequences—additional automatic spending cuts known as the “sequester”—are scheduled to begin in March 2013.

The sequester’s automatic across-the-board cuts will affect more than just nondefense discretionary spending. They will also cut defense spending and several mandatory programs; most mandatory spending, however, will be exempt. But if the sequester is allowed to go forward, it will also cut nondefense discretionary spending even further than it has already been cut by the Budget Control Act caps. If fully implemented, the sequester will reduce the nondefense discretionary part of the federal budget by $331 billion from 2013 through 2022, a cut of an additional 5 percent from the already-lower capped levels. The result: reducing nondefense discretionary spending even further from the already projected historic lows. Instead of totaling 3.2 percent of GDP in 2017, nondefense discretionary spending would total less than 3 percent of GDP and would be on its way down to 2.6 percent by 2022. This is less than two-thirds of what was previously its lowest level.

If Congress allows the sequester to go into effect, there will be an immediate, across-the-board uniform cut to all nonexempt programs. In subsequent years, however, the sequester will cut discretionary spending not through a uniform, across-the-board cut, but through lowering the Budget Control Act caps even further.

The Budget Control Act’s discretionary spending caps—both the ones now in place and also the lower levels that will take effect if the sequester kicks in—do not mandate how the cuts they force would be apportioned. It will be up to Congress each year to pass appropriations bills that bring total spending in under the limit. This means that Congress could decide to share the burden equally, applying each year’s cuts proportionately to every line item, or that Congress could decide to cut some programs more than others. There is no way to accurately predict how these cuts will be implemented. But by employing the assumption that Congress will apply the cuts in rough proportion to each of the broad categories, we can begin to get a sense for how the Budget Control Act and the sequester will impact federal spending in specific areas.

Economic investments

This nondefense discretionary budget category includes funding to maintain and improve the nation’s transportation infrastructure and educational system; support scientific, technological, and health care research and development; and support programs to boost regional and local economic development. The three largest “programs” under this category are the Federal Highway Administration, (which spent $43 billion in 2012), the National Institutes of Health ($32.7 billion), and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education ($25.3 billion). Overall spending in this category totaled $245.3 billion in 2012—40 percent of total nondefense discretionary spending but less than 7 percent of all federal spending. Discretionary spending on economic investments in 2012 was equivalent to about 1.6 percent of GDP. This is exactly in line with the average amount spent in this area in the past 10 years.

Under the Budget Control Act caps, by 2016 discretionary spending on economic investments will fall below their lowest levels of the past decade, in both inflation and population-adjusted terms. As a share of GDP, spending in this area will be lower in 2022 than it has been at any point since 1962.

The sequester will peel away another $132 billion over the next 10 years from this category of nondefense discretionary spending. If implemented, spending in this area in 2014 will already be lower in inflation and population-adjusted dollars than it was at any point in the past 10 years, and by 2022 spending in this category will be a full 16 percent below its lowest level of the past decade.

Low-income assistance and antipoverty efforts

This category includes housing, nutrition, child care, and energy assistance to low-income families. It also includes some assorted other social services. More than 80 percent of all spending in this area flows through just three federal bureaus: Public and Indian Housing programs ($36.3 billion), the Administration for Children and Families ($17 billion), and the Food and Nutrition Service ($7.4 billion). In 2012 overall discretionary spending in this category totaled $75.6 billion, roughly 12 percent of total nondefense discretionary spending and slightly more than 2 percent of all federal spending. Discretionary spending on low-income assistance in 2012 was equal to about 0.5 percent of GDP, which is the average amount spent in this category over the past 10 years.

Under the Budget Control Act caps, discretionary spending on low-income assistance in 2013 is already likely to be at its lowest levels of the past decade in both inflation and population-adjusted terms. In each of the past 10 years, this category of spending has totaled about 0.5 percent of GDP. By 2022, however, with the caps in place, spending will decline to 0.3 percent of GDP.

The sequester will cut another $41 billion from these programs. If implemented, discretionary spending on low-income assistance as a share of GDP will be lower in 2022 than it has been at any time since 1978.

Veterans

This category includes various benefits and services for our nation’s veterans. Most of the discretionary spending for veterans goes toward their health care services. The Veterans Health Administration spent $50.1 billion in 2012, which accounted for 86 percent of the $58.4 billion in overall discretionary spending on veterans last year. Discretionary spending on veterans made up about 9 percent of total nondefense discretionary spending and 1.6 percent of all federal spending in 2012. It was equivalent to 0.4 percent of GDP, which is higher than the average of 0.3 percent from the past 10 years.

Discretionary spending on veterans has grown substantially in recent years. From 2002 to 2007 discretionary outlays on veterans’ services—mainly health care—hovered around 0.25 percent of GDP. Starting in 2008 spending began to grow such that by 2012 it was about 0.4 percent of GDP. Over the next several years, the Budget Control Act caps will halt this trend and begin to reverse it. By 2022 discretionary spending on veterans will be back at 2008 levels—roughly 0.3 percent of GDP.

If the sequester goes into effect, this area of spending will be largely unaffected in the first year because the Department of Veterans Affairs is exempt from the across-the-board automatic cuts in the sequester. In future years, however, the sequester operates by lowering the existing Budget Control Act caps, not through an automatic across-the-board cut, and those caps will affect the Department of Veterans Affairs. As a result, though spending in this area will not be reduced by the sequester in fiscal year 2013, spending would go down in subsequent years. Under the sequester, therefore, discretionary spending on veterans would be reduced by about $34 billion from 2014 through 2022.

Law enforcement and justice

This category includes federal efforts aimed at crime prevention and investigation, border protection and immigration enforcement, the federal prison system, and U.S. attorneys and the federal courts, including the Supreme Court. The three largest items in this category are Customs and Border Protection (which spent $10.8 billion in 2012), the federal prison system ($6.8 billion), and the federal courts ($6.2 billion). Other notable bureaus in this category include the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Marshals, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and the Secret Service. Altogether, discretionary spending on law enforcement and justice totaled $54 billion in 2012—about 9 percent of all nondefense discretionary spending and 1.5 percent of all federal spending. Discretionary spending in this area amounted to 0.3 percent as a share of GDP, about the same as the average spending in this category during the past 10 years.

Under the caps imposed by the Budget Control Act, federal discretionary spending on law enforcement and justice will fall below 0.3 percent of GDP by 2017. That is lower than in 2007, the lowest spending year of the past decade. By 2022 spending levels will match those of 1998. If the sequester is implemented, another $32 billion will be cut from this category through 2022.

International affairs

This category includes development, humanitarian, and security assistance to foreign countries. It also includes the maintenance of and security for all U.S. embassies, ambassadors, and foreign-service officers. In 2012 development and humanitarian assistance totaled $23.4 billion, security assistance totaled $12 billion, and the basic operations of U.S. foreign policy cost $13.5 billion. The federal government’s total bill for international affairs in 2012 was $49.8 billion, which represented 8 percent of all nondefense discretionary spending and 1.4 percent of total federal spending. Discretionary spending on international affairs was equal to 0.3 percent of GDP in 2012, the same as the average from the previous 10 years.

Spending on international affairs is the one category of nondefense discretionary spending that is projected to continue to grow under the Budget Control Act caps, at least in the first few years. In 2012 the federal government spent just more than 0.3 percent of GDP in this area. Even with the caps, that percentage is projected to grow to 0.35 percent of GDP by 2014. Only then will the caps start to force a decline. This projection, however, includes about $10 billion a year in “war spending”—mainly funding for operations in Afghanistan—that is exempt from the caps. Without that exempt spending discretionary spending on international affairs will begin falling immediately under the caps, just as the spending in every other category will. By 2022 it will decline to just 0.2 percent of GDP—lower than at any point since 1962. The sequester would cut another $26 billion from this category through 2022.

Energy, agriculture, natural resources, and the environment

This category includes a variety of efforts to improve the nation’s energy and agricultural resources. These include several programs run by the Department of Energy to study energy efficiency, fossil fuels, renewable energy sources, energy reliability, and even nuclear waste disposal, for a total of $13.7 billion in 2012. They also include agencies within the Department of Agriculture, including the Agricultural Research Service ($1.2 billion) and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture ($1.2 billion). The category also includes the national parks system and programs focused on environmental protection and conservation. The Environmental Protection Agency ($10 billion) features prominently in this category, as do an assortment of smaller agencies such as the National Park Service ($2.9 billion), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ($1.6 billion), and the U.S. Geological Survey ($1.1 billion). Altogether, discretionary spending in this category totaled $59.3 billion in 2012, about 10 percent of all nondefense discretionary spending and 1.7 percent of all federal spending. This amounted to 0.4 percent of GDP.

Under the Budget Control Act caps, discretionary spending in this category is set to decline to its lowest level on record by 2015. From 2002 to 2012, spending for this category averaged 0.35 percent of GDP. Under the budget caps, spending in FY 2014 will already be below that average. The sequester will cut an additional $27 billion from this area through 2022.

General government operations and miscellaneous activities

This final category includes the general operating expenses of the federal government and any activities not contained in the other categories—the most significant of which are public health, disease control and prevention, and consumer product safety. The single largest agency in this category is the Federal Emergency Management Agency ($11.6 billion), followed by the Internal Revenue Service ($11.1 billion). This category is also home to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ($6 billion), the Food and Drug Administration ($1.9 billion), and of course, the operating expenses of the U.S. Congress ($2.2 billion). A number of smaller agencies and programs can also be found here, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics—which, among other tasks, produces the monthly employment report—the Small Business Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Federal Election Commission, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Discretionary spending in this category totaled $77.2 billion in 2012, which represented 12 percent of all nondefense discretionary spending, about 2.2 percent of all federal spending, and 0.5 percent of GDP.

FY 2012 spending on basic government operations and other miscellaneous activities not contained in the other categories was already just below the average of 0.5 percent of GDP for the decade from 2002 through 2012. The Budget Control Act caps will further reduce spending in this category, and by 2015 will cut it down to its lowest level on record, about 0.4 percent of GDP. The sequester will further reduce spending in this category by an estimated $38 billion. If the sequester is implemented, by 2022 spending will be a full 20 percent lower than the lowest point in the past 50 years.

Conclusion

Nondefense discretionary spending may not have a very descriptive name, and most Americans may have little concept of what it is exactly. But, in fact, many of the federal government’s most popular and important functions are funded by nondefense discretionary dollars. Everything from border control to the Smithsonian Institution, from food inspections to cancer research, and from highways to schools is contained within the nondescript category of nondefense discretionary spending. Over the past several years, however, Congress and President Obama have enacted legislation that will dramatically curtail federal spending on all of these vital activities.

The Budget Control Act’s caps will reduce nondefense discretionary spending to historically low levels, and the impending sequester will cut even deeper. There can be no doubt that such enormous cuts and such low levels of federal investment will have noticeable impacts on ordinary Americans. It remains to be seen, however, if Americans will tolerate these impacts.

Methodology

The calculations in this issue brief are based on the most recent Congressional Budget Office projections, released in August 2012. Those CBO projections do not allocate the cuts that would be necessary to meet the Budget Control Act caps, or the lower sequester-level caps. Rather the CBO projects all budget accounts without the effect of the caps, and then reports the overall magnitude of the cut necessary to bring nondefense discretionary spending into compliance with the Budget Control Act. For this brief, those cuts were divided proportionately by affected individual budget account, and then aggregated to the larger categories.

Michael Linden is the Director of Tax and Budget Policy at the Center for American Progress.