The economy is still picking through the pieces of the mess wrought by congressional conservatives’ latest fiscal drama. It is clear that the government shutdown and near default on government debt contributed to a slowdown in economic growth this fall. This slowdown followed modest growth from the fall of 2012 through the summer of 2013. Business investment in particular slowed, partially due to the economic uncertainty following congressional conservatives’ brinksmanship on government spending, taxes, and the debt ceiling—the amount the government can borrow without congressional approval. Congress now has an opportunity to develop a pro-growth budget and end the string of fiscal showdowns that have come to signify the policy approach of a radical conservative minority in Congress. A pro-growth budget would boost economic growth and job creation by investing in infrastructure and education and creating predictability for America’s businesses.

Calculations based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, or BEA, for the past few quarters—from the end of 2012 through the summer of 2013—show that business investment has slowed. Business investment fell precipitously during the Great Recession, from 13.4 percent of gross domestic product, or GDP, in December 2007 to 11.4 percent of GDP in June 2009. It eventually began to recover again and reached its latest high point with 12.3 percent of GDP in 2012 before leveling off throughout 2013. Importantly, though, investment started to slow even before that, specifically in the third quarter of 2011—the same quarter during which radical conservatives brought the U.S. government near its first ever default on its debt.

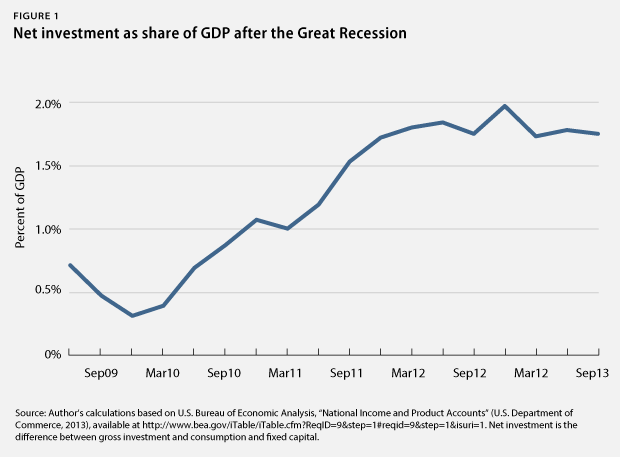

And the situation is actually worse than these calculations on overall investment spending suggest. Investment goods, especially computers and software, depreciate more quickly than in the past. Businesses consequently need to spend more money today to replace obsolete capital such that the net increase in usable stuff is relatively small. Net investment—the amount of investment that does not go to replace obsolete investment goods—fell from 3.4 percent of GDP in December 2007 to 0.7 percent of GDP in June 2007. It had recovered to 2 percent of GDP by the end of 2012 before again dropping below 2 percent in 2013. Net investment had already slowed prior to 2013, similar to total investment, starting with the third quarter of 2011. (see Figure 1)

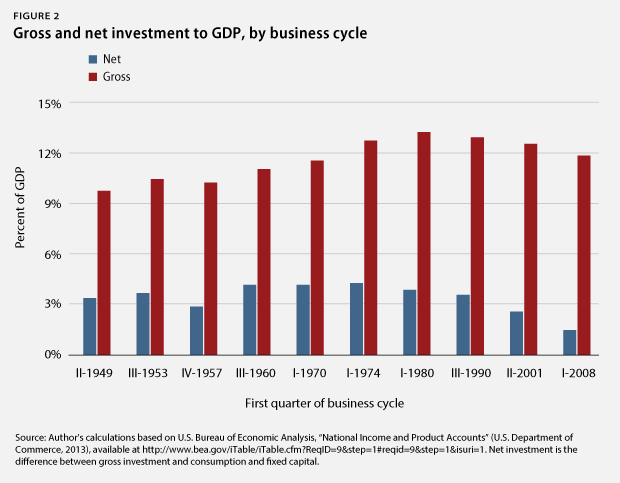

This slowdown hurts current economic growth since businesses are spending less and thus need to buy less from equipment manufacturers and construction companies. Slow investment spending in the present can also hurt U.S. competitiveness in the long run, especially since the 2012 slowdown came amid modest investment for this business cycle—from December 2007 to September 2013—to begin with. Investment in equipment such as computers and trucks and structures such as manufacturing plants and office buildings amounted to a total of 11.9 percent of GDP for the current business cycle—the lowest average investment since the early 1970s. (see Figure 2) And net investment averaged a historically low 1.5 percent of GDP during this business cycle—well below the second-lowest 2.6 percent recorded during the previous business cycle from March 2001 to December 2007. The U.S. economy clearly needs more business investment to grow and remain globally competitive.

The economic wound brought on by the investment slowdown is probably self-inflicted. Businesses likely hit the pause button on their investment spending as they became worried about congressional conservatives’ brinkmanship over the federal budget and debt. It is in particular the flattening of net investment in 2013 that makes this point. For instance, the Association of Financial Professionals, which represents financial leaders at corporations and pension plans, found in their survey at the end of 2012 that 51 percent of respondents were somewhat more hesitant to invest and 13 percent were significantly more hesitant to invest because of “Washington’s perceived inability to resolve budgetary and economic issues.” That is, business leaders were rightly worried that the coming negotiations over the fiscal cliff—the simultaneous expiration of tax cuts and onset of spending cuts in January 2013—would bring little resolution and create tremendous uncertainty over taxes, government spending, and interest rates. The fiscal drama that unfolded over the 10 months from December 2012 to October 2013 unsurprisingly resulted in slower business investment.

It is difficult to explain the business slowdown in 2013 in any other way. Businesses have been highly profitable and accumulating large amounts of cash, and banks have been consistently easing their lending standards for loans to small and large businesses alike during this time. That is, businesses did not suffer from a lack of money to invest. The investment slowdown cannot have been the result of the onset of Obamacare since the Affordable Care Act went into effect in early 2010 and businesses increased their investments for the first few years the law was on the books. Moreover, the European crisis abated in 2013 and oil prices leveled off, which should have led to more, not less, investment. The manufactured fiscal crises are one likely culprit for the slowdown in investment spending in 2013. And it is possible that the ongoing fiscal drama contributed to the earlier weakening, starting in the third quarter of 2011, as well.

The fiscal standoffs of the past two years have already taken a toll, and U.S. competitiveness cannot afford more of the same. Now is the time for Congress to fix this self-inflicted fiscal mess by enacting a pro-growth budget that focuses on investments in infrastructure and education. Such a budget would also create the economic certainty that businesses look for and boost private sector investments.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor in the Department of Public Policy and Public Affairs at the University of Massachusetts Boston.