The U.S. Census Bureau today released new data on poverty in 2011, poverty being defined as a family of four with an annual income of less than $23,000. The data reveal that 46.2 million people (15 percent) lived in poverty last year, not statistically different from 2010.

Just looking at these headline numbers, however, misses some of the most important things the data tells us about growing income inequality, the state of the middle class, the role of public policy in alleviating poverty, and how the key policy choices in front of us on jobs, health care, budget, and taxes could affect these trends for years to come.

Here are five key things you should know about the 2011 poverty data:

- This is the second time on record that our economy grew, yet low and middle-income families did not share in the gains.

- Social insurance programs keep millions of people out of poverty.

- The poverty data don’t register the importance of tax credits for working families and nutrition assistance programs.

- We need to focus on jobs, jobs, jobs.

- Child poverty today will cripple our long-term economic competitiveness.

Let’s take a look at each of these five points in turn to demonstrate the true state of poverty in our nation and the best means to fight it.

This is the second time our economy grew, yet low and middle-income families did not share in the gains

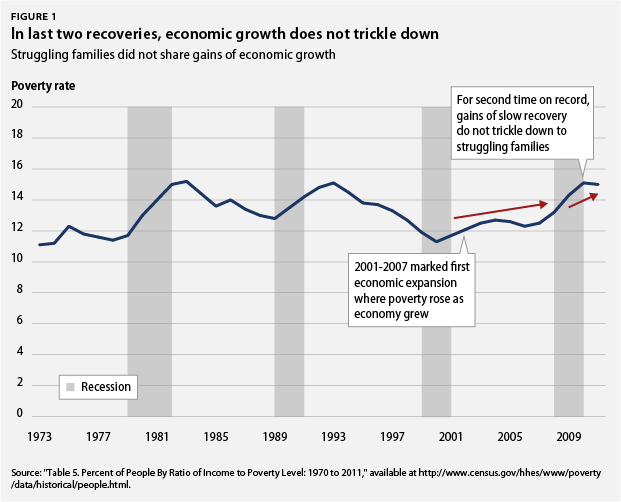

The last economic cycle between the brief recession of 2000-2001 and before the beginning of the Great Recession of 2007-2009 was the first time on record when profits and productivity went up but poverty increased, meaning that struggling families had already been left out of the gains of economic growth before the Great Recession even hit. In fact, through two recessions and two recoveries, the poverty rate continued to climb significantly in 7 out of the past 11 years.

Even though the Great Recession ended three years ago, the gains of this recovery remain unshared. While incomes in the top 5 percent grew, the poverty rate did not budge since last year and middle-class incomes declined. (see Figure 1)

Social insurance programs keep millions out of poverty

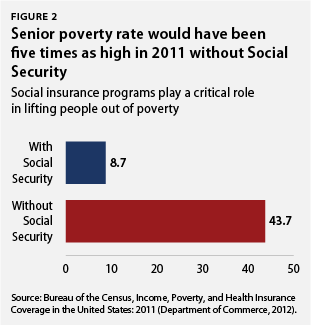

The poverty rate is too high, but we cannot forget that it would have been significantly higher without social insurance programs such as Social Security and unemployment insurance. In 2011 Social Security kept 21.4 million people out of poverty, including 14.5 million seniors. Without it the senior poverty rate would have been five times as high. (see Figure 2)

Unemployment insurance played a similar role in helping families whose breadwinner lost a job through no fault of his or her own to keep their heads above water. In 2011 unemployment insurance kept more than 2.3 million people out of poverty, fewer than in 2010 when 3 million people were lifted above the poverty line. Unfortunately, a premature pullback in unemployment insurance likely dampened the powerful antipoverty effects of this program. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, there was a $36 billion inflation-adjusted decline (approximately 25 percent) in unemployment insurance payments from 2010 to 2011, some of which is due to people finding jobs or timing-off benefits.

More than a quarter of the decline, however, resulted from the expiration at the end of 2010 of Federal Additional Compensation, an initiative that was part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 that provided an additional $25 a week in unemployment benefits.

The poverty data don’t register the importance of tax credits for working families and nutrition assistance

While poverty increased under the traditional measure in the past several years and remained steady from 2010 to 2011, this metric does not take into account many of the important policy steps the Obama administration implemented to alleviate hardship and provide a pathway back to the middle class. The Recovery Act included the expansion of the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit for working families that kept 1.6 million people out of poverty in 2010.

The expansion of these two tax credits is set to expire at the end of the year. If Congress fails to act, millions of families could be pushed into poverty or experience deeper poverty. Overall, the entire earned income tax credit kept 5.7 million people above the poverty line in 2011. (see Figure 3)

Similarly, nutrition assistance played a big role in keeping people out of poverty and prevented a significant increase in the share of families struggling against hunger. Between 2007 and 2008, as our economy worsened in the run up to the Great Recession, there was a big jump in household food insecurity. Yet as poverty rose dramatically between 2008 and 2009, food insecurity, a key indicator of family hardship and deprivation, did not. It remained stable even as poverty steadily climbed over the subsequent years.

This can be attributed in part to the expansion of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the 2009 Recovery Act, which helped families afford food even as their incomes dropped. In fact, counting this nutrition aid as income would have lifted 3.9 million people above the poverty line in 2011. (see Figure 4)

We need to focus on jobs, jobs, jobs

Unemployment and poverty share a close relationship. In fact, that the poverty rate stabilized between 2010 and 2011 can partly be attributed to an increase in the number of full-time year-round workers over the same period. Yet both our poverty and unemployment rates remain too high as conservatives in Congress have continually obstructed jobs bills that would have put laid-off teachers and first responders back on the job; put people to work building roads, bridges, and schools; and connected low-income and long-term unemployed workers with subsidized employment in their local communities.

Child poverty today will cripple our long-term economic competitiveness

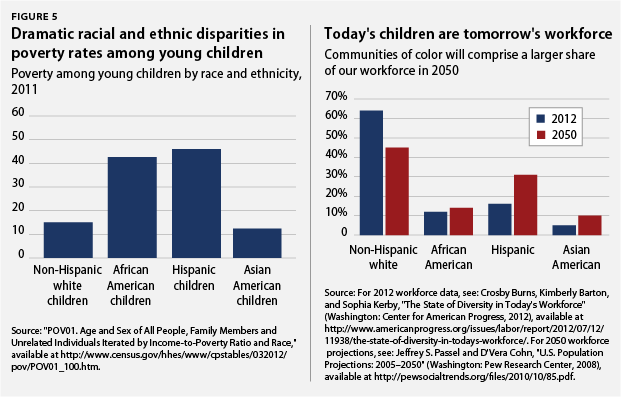

A particularly troubling trend in the data is persistent racial and ethnic disparities, particularly among young children under age 5. In 2011 more than one in four children (25.1 percent) under age 5 lived in poverty, but the rates for black and Latino children were significantly higher, at 42.7 percent and 36 percent, respectively.

Research shows that poverty among young children carries consequences far beyond their childhood in everything from educational outcomes and worker productivity to long-term health costs. The majority of children under one year of age today are children of color, and by 2042 our nation will have no clear racial or ethnic majority, a year in which these children will be in the prime of their working lives. (see Figure 5). Tackling child poverty and racial and ethnic disparities now is critical for our long-term economic competitiveness.

Conclusion: Policy matters

These numbers could not be timelier. In the context of widening income inequality, Congress will be debating whether or not to extend tax cuts for the top 2 percent of households this year, or whether to cut the federal deficit by asking struggling families to sacrifice nutrition, health care, and early education. The recent poverty data does not reflect the key role that policies on the chopping block, such as tax credits for working families and nutrition assistance, play in boosting the incomes of struggling families. As Congress seeks to reduce our long-term deficits, it is critical that they understand the powerful antipoverty effects of these policies and the role they play in creating greater economic opportunity for struggling families.

The data also underscore the key role that federal unemployment benefits play in keeping those who lost a job through no fault of their own above the poverty line. On December 31, 2012, the entire federal unemployment insurance program will expire. If Congress fails to continue providing federal unemployment benefits for workers who have been out of a job for more than six months, this will be the first time they have failed to act when the unemployment rate was this high, and they will likely send millions of families with an unemployed worker into poverty.

Finally, the data underscore the need for Congress to focus first and foremost on job creation. Robust and shared economic growth that creates good jobs will be the centerpiece of a strategy to dramatically reduce poverty.

There is much at stake for struggling families in the pending lame duck session between the November national elections and the new Congress in 2013. Poverty reduction and deficit reduction historically go hand in hand, and the Center for American Progress came up with a plan that would dramatically reduce poverty while balancing the budget by 2030. It’s about choices. And the 2011 poverty data should serve as a wake-up call for Congress to make choices that grow our economy equitably, invest in economic opportunity for struggling families, and tackle the deficit in a way that does not exacerbate poverty and inequality.

Melissa Boteach is Director of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.