In response to broad public backlash over his administration’s policy of separating children from their parents at the United States’ southwest border, President Donald Trump signed an executive order in June 2018 that purports to replace family separation with potentially indefinite family detention.1 Numerous Trump administration officials have supported such policies under the belief that they would deter families from attempting to enter the United States.2

Internal memos from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), however, illustrate that the administration’s family separation policy has not had its intended effect.3 A new analysis of data from a longer period of time illustrates that family detention has not acted as a deterrent either. Altogether, the data show that both family detention and family separation policies have not deterred families from coming to the United States in the past—and are unlikely to do so in the future.

Family detention

Detaining families in response to increased arrivals along the southwest border is not new, even if President Trump’s zero-tolerance policy that separates families is. In response to the growing number of arrivals of Central American families and unaccompanied children in 2014, for example, the Karnes County Residential Center was converted from a civil detention facility into a family detention facility that July.4 Families were also detained at a temporary facility in Artesia, New Mexico, before the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, opened in December 2014. The Obama administration’s expanded use of family detention represented a major immigration policy shift, considering that the administration had largely abandoned the practice in the years prior to July 2014.5 When delivering remarks at the opening of the South Texas Family Residential Center, then-DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson stated, “I believe this is an effective deterrent.”6

To explore the question of whether the expanded use of family detention in July 2014 deterred subsequent arrivals of families, this analysis evaluates changes over time—from October 2011 to June 2018—in the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border.7 Apprehensions are widely used as an indicator of flows.8

Using interrupted time series analysis (ITSA), this analysis estimates the relationship between the expanded use of family detention and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border. (see Appendix) The analysis finds that the number of families arriving at the border before July 2014—when the Karnes County Residential Center was converted to a family facility—was increasing. But there was no statistically significant decrease in apprehensions of families at the border after the widespread expansion of family detention in July 2014. (see Table 1 in the Appendix)

Moreover, a series of models were run specifying pseudo-interventions—meaning different start dates for the expanded use of family detention—to address the possibility that policy changes need time to take effect. The pseudo-interventions analyzed include the months shortly after the conversion of the Karnes County Residential Center; the month of the opening of the South Texas Family Residential Center; and the three months after the opening of the South Texas Family Residential Center.9 These models produce qualitatively similar results: The expanded use of family detention is not statistically significantly related to decreases in the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border.

Family separation

Beginning in July 2017, as The New York Times and Vox reported, the Trump administration piloted a zero-tolerance policy wherein all individuals caught attempting to enter the United States without authorization were referred to the U.S. Department of Justice for prosecution. Parents migrating with their children were then separated from their children.10 In other words, the separation of children from their parents at the southwest border started even before the administration’s blanket zero-tolerance policy officially began in April 2018.11 In March 2017, in response to whether the Trump administration planned to separate children from their parents, current White House chief of staff John Kelly stated, “[I]n order to deter more movement along this terribly dangerous network, I am considering exactly that.”12 Despite widespread outrage over family separations, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reiterated the administration’s belief in the deterrent effect of family separation: “We cannot and will not encourage people to bring their children or other children to the country unlawfully by giving them immunity in the process.”13

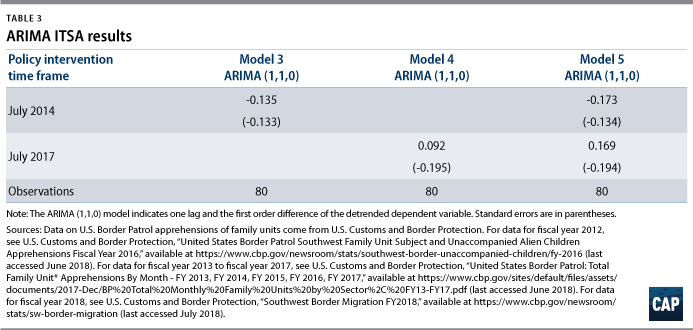

The monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border has not decreased as a result of family separation. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the use of family separation and the monthly number of apprehensions while controlling for the expanded use of family detention in July 2014. It shows that the monthly number of apprehensions was increasing before the expanded use of family detention in July 2014, continued to increase after, and increased again after the zero-tolerance pilot in July 2017. (see also Table 2 in the Appendix)

Seven additional models were run specifying pseudo-interventions, which include the months during which the zero-tolerance pilot was in effect—August 2017 to November 2017—as well as the three months after the zero-tolerance pilot ended.14 These models produce qualitatively similar results, wherein instead of having a deterrent effect, the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border increased significantly after the pseudo-interventions.

Seasonal trends

Figure 1 also illustrates the strong seasonal trends in the monthly number of apprehensions at the southwest border. Even after taking seasonal trends into account, however, there is still no evidence that the policies analyzed in this brief act as a deterrent.

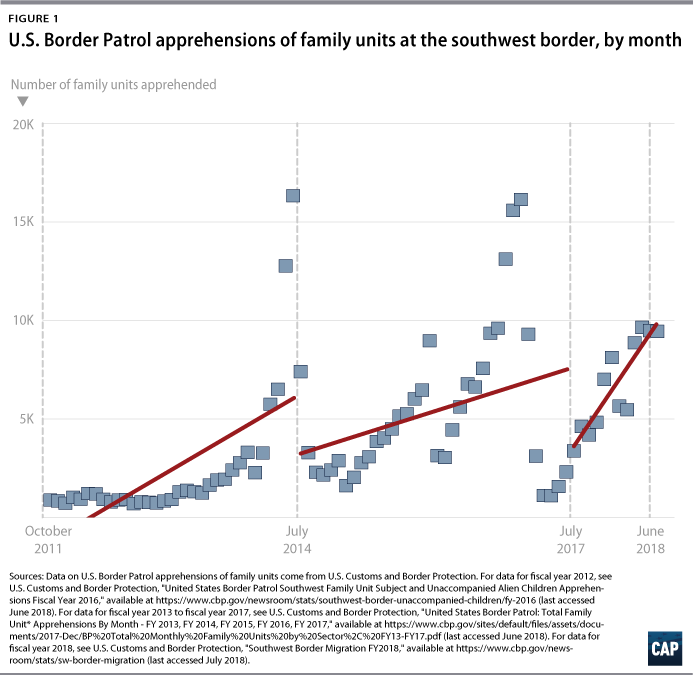

Figure 2 makes these seasonal trends clearer.15 In 2014, for example, the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the border increased beginning in late winter—specifically in February and March—and continued to increase through spring—particularly in April, May, and June—before beginning to decline in July. The figure also shows that a second peak may have emerged in October, November, and December 2017, but it is too soon to tell if this seasonal trend will hold. This is because 2017 was the first year in the time series that saw large numbers of apprehensions of families during these months. Notably, the seasonal summer decrease in family apprehensions appears to lag one month behind the seasonal summer decrease in total apprehensions—including families, unaccompanied minors, individuals traveling alone, and others—which dips beginning in June.

Because the data on the monthly number of family apprehensions at the southwest border exhibit seasonal trends, it is important to check the robustness of the results using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) ITSA. ARIMA modeling allows one to evaluate the extent to which an intervention has an effect on an outcome of interest that is independent from underlying time trends. (see Appendix for full explanation)

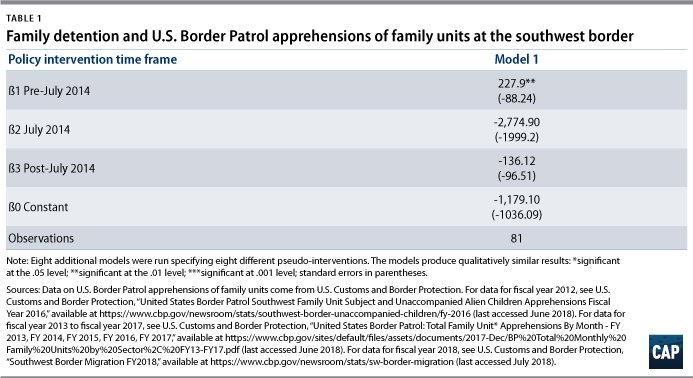

Even after taking seasonal trends into account, however, neither the expanded use of family detention nor the use of family separation is statistically significantly related to decreases in the monthly number of family apprehensions. In other words, the data continue to show that these policies do not act as deterrents to families attempting to enter the United States. (see Table 3 in the Appendix) Fifteen different models were run specifying pseudo-interventions; these models produce qualitatively similar results.

Conclusion

The Obama administration used family detention in response to an increase in Central American families and unaccompanied children arriving at the southwest border. The Trump administration has turned instead to family separation and potentially indefinite detention. Both policies, however, have been shown to be ineffective deterrents.

Tom K. Wong is a senior fellow for Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress and associate professor of Political Science at the University of California, San Diego. His latest book is The Politics of Immigration: Partisanship, Demographic Change, and American National Identity.

Appendix

Analyzing the relationship between family detention and monthly apprehensions over time

The analyses in this brief use ITSA to analyze the relationship between the expanded use of family detention as a deterrent policy and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border.16 ITSA is a quasi-experimental research design that is used to evaluate trends before, immediately following, and during the period after an intervention such as a policy change. ITSA estimates three main parameters: ß1 is the slope or trajectory of the outcome variable before the start of the intervention; ß2 is the change in the level of the outcome variable in the period immediately following the start of the intervention; and ß3 is the treatment effect of the intervention over time.

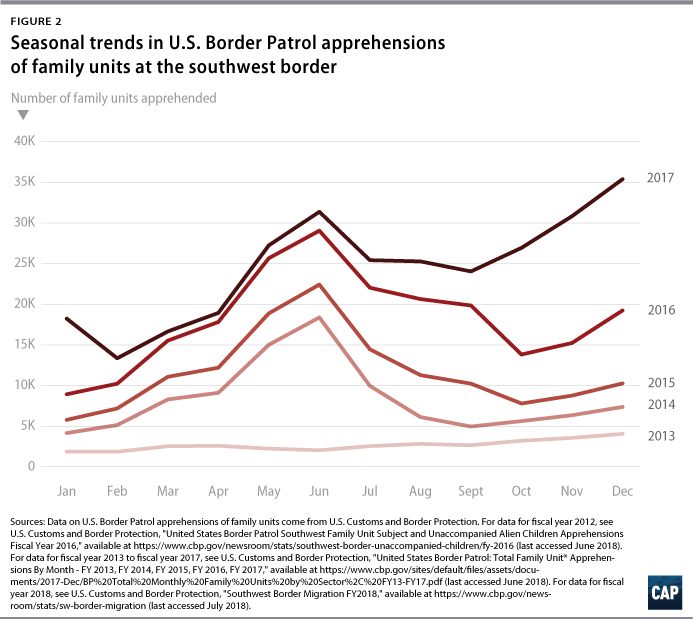

Table 1 presents the results of the ITSA analysis. Model 1 estimates the relationship between the expanded use of family detention—measured by the conversion of the Karnes County Residential Center in July 2014 (ß2) and each subsequent month thereafter (ß3)—and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border.

As the table shows, in Model 1, the ß1 coefficient is positive and statistically significant, which affirms that the monthly number of apprehensions was increasing before July 2014. Both the ß2 and ß3 coefficients are statistically insignificant, however, which suggests that the expanded use of family detention is not statistically significantly related to an immediate or long-term decrease in the monthly number of apprehensions at the southwest border.

Analyzing the relationship between family separation and monthly apprehensions over time

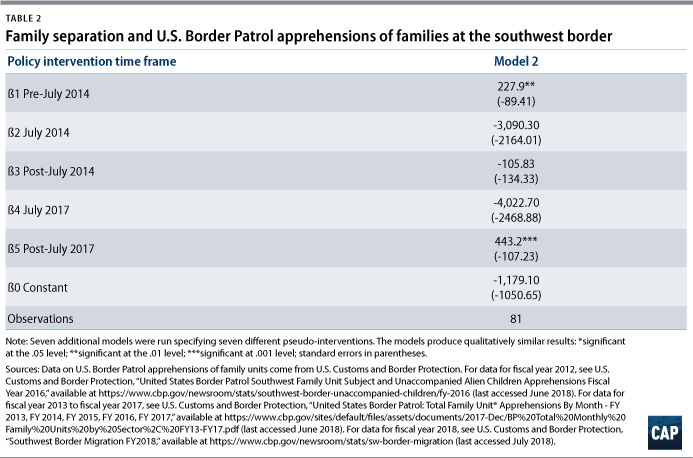

Table 2 analyzes the relationship between the use of family separation as a deterrent policy and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border. Model 217 estimates the relationship between family separation, measured by the beginning of the zero-tolerance pilot in July 2017 (ß4) and each subsequent month thereafter (ß5) as well as the monthly number of apprehensions, while controlling for the expanded use of family detention in July 2014.

As the table shows, in Model 2, the ß1 coefficient remains positive and statistically significant, affirming that the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of families at the southwest border was increasing before July 2014. Both the ß2 and ß3 coefficients remain statistically insignificant, affirming the results in Model 1. The ß4 coefficient is statistically insignificant, which suggests that family separation is not statistically significantly related to an immediate decrease in the monthly number of apprehensions. Unexpectedly, the ß5 coefficient is positive and highly statistically significant (p < .001), which means that instead of family separation having a deterrent effect, the monthly number of apprehensions of families has increased significantly after July 2017.

Re-estimating the relationship by removing time trends

ARIMA is the primary method of analyzing quasi-experimental time series data. The ARIMA interrupted time series method removes time trends—the so-called noise—in order to isolate the impact of an intervention—known as the signal. ARIMA modeling begins by identifying and removing noise, or the extent to which the data in a time series can be accurately predicted by time itself. Identifying and removing noise allows one to evaluate the extent to which an intervention has an effect on an outcome of interest that is independent from underlying time trends.

Table 3 reports the results of the ARIMA interrupted times series analysis. Model 3 shows that after identifying and removing time trends,18 there is no statistically significant relationship between the expanded use of family detention, measured by the conversion of the Karnes County Residential Center in July 2014 and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions. Model 4 shows that after identifying and removing time trends,19 there is no statistically significant relationship between family separations, measured by the beginning of the zero-tolerance pilot in July 2017 and the monthly number of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions. Model 5, which includes both interventions, produces qualitatively similar results.20