Responding effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic requires a real-world understanding of the daily struggles that women of color face and the critical role they play in their families and communities. The rapid, unrelenting spread of the virus raises several challenges that are particularly important to address: widespread economic and employment instability, skyrocketing caregiving needs without sufficient supports, and added pressures exacerbating workplace barriers that already limit opportunities. These challenges should not be viewed in a vacuum, but rather understood in the broader structural and cultural contexts in which they occur.

Long-standing structural inequities—fueled by racism, sexism, ethnic stereotypes, and other forms of bias—have created an uneven landscape that makes it difficult for many people of color to secure jobs with solid wages and opportunity for advancement; access quality health care that is timely and responsive; and reside in communities with the essential services necessary to live healthy lives. Furthermore, deep-rooted cultural attitudes and stereotypes about women of color have too often devalued their work and deprioritized their needs, leaving them without helpful supports. Both of these dynamics play a role in shaping the experiences of women of color and the potential impacts of the COVID-19 crisis.

COVID-19 is undermining the earnings and economic stability of women of color

Women of color are integral to the economic stability of their families. Any erosion of their earnings would be disastrous, worsening instability and robbing families of essential resources. Data consistently show that, across all family structures, women of color play a vital role in providing economic support on which their families rely to make ends meet. In families with children, many women of color who are mothers are also breadwinners, meaning that they are the sole earner for their family or earn as much as or more than their partner.1 A Center for American Progress analysis of 2018 data from the Current Population Survey found that 67.5 percent of Black mothers and 41.4 percent of Latina mothers were the primary or sole breadwinners for their families, compared with 37 percent of white mothers.2 Other research analyzing 2014 American Community Survey data found that 67.1 percent of Native American mothers and 44.2 percent of Asian and Pacific Islander mothers provide at least 40 percent of their family’s income.3 Furthermore, mothers in lower-income families—disproportionately women of color4—are far more likely to be breadwinners than mothers in higher-income families: In 2018, an estimated 70 percent of mothers in families in the lowest economic quintile were primary or sole breadwinners, compared with 31 percent of mothers in families in the top income quintile.5

Looking at families more broadly, data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement show that Hispanic women—of any race—and Black women are far more likely than white and Asian women to be single heads of households and, therefore, the main source of support for their family.6 In 2018, households headed by Black women constituted 41.2 percent of Black family households, and households headed by Hispanic women constituted 24.4 percent of Hispanic family households. In contrast, white women headed only 12.7 percent of white family households, and Asian American women headed 11.7 percent of Asian American family households.7

While COVID-19’s disruption of industries and economic sectors impairs the ability of women of color to support their families, it is worth noting that these disruptions are occurring on top of existing inequities that have long undermined the economic status of women of color. In addition to the substantial economic responsibilities for their families, women of color continue to experience pay disparities that reduce their overall earnings and undermine their economic stability. Women of color consistently earn less than their white and male counterparts. Among full-time, year-round workers, for every dollar earned by white men, Hispanic women earn 54 cents, Native women earn 57 cents, Black women earn 62 cents, white women earn 79 cents, and Asian women earn 90 cents.8 And while Asian American women tend to earn the highest wages of all women, there are wide variations across subpopulations, with some groups experiencing a much larger pay gap than others. For example, among full-time, year-round workers, Nepali women earn 50 cents and Cambodian women earn 57 cents for every dollar earned by white men.9

Furthermore, many women of color are less likely to have the wealth and savings necessary to go for an extended period of time without earnings—something that is now necessary on a massive scale as people lose their jobs due to COVID-19. Women of color experience both a gender and racial wealth gap; 2015 research examining overall individual wealth—in this case, the combined assets available to individuals, such as cash, retirement funds, investments, and real estate—found that the median wealth for single Black women is $200 and the median wealth for single Hispanic women is $100, compared with $15,640 for single white women and $28,900 for single white men.10 This means that in addition to having lower earnings, many women of color are far less likely to have the resources necessary to absorb and withstand a significant drop in earnings precipitated by the pandemic.

Mitigating the effects of COVID-19 must take into account all of these economic realities for women of color. In order to help all families—especially those that are most vulnerable—stay afloat, state and local policymakers should evaluate any relief strategies to assess their effectiveness in addressing the immediate and long-term challenges associated with gender and racial gaps in wages and wealth. These strategies should include increasing access to income supports, such as paid leave, that provide full wage replacement; making increased pay available for essential workers; requiring increases to the minimum wage; eliminating subminimum wages for tipped workers and workers with disabilities; and bolstering equal pay enforcement.11

Policymakers should also invest in tools to help improve access to banking and other financial services for low-income individuals, as such services would allow them to strengthen their credit and financial records, giving them a pathway toward building savings. Individuals who lack a bank account are disproportionately Black and Hispanic: In 2017, an estimated 16.9 percent of Black households and 14 percent of Hispanic households were unbanked, whereas only 2.5 percent of Asian households and 3 percent of white households were unbanked.12 In addition, research examining financial access in Native American communities found that 16.9 percent of Native Americans were unbanked in 2013.13

Disruptions to employment may have especially harsh impacts on women of color

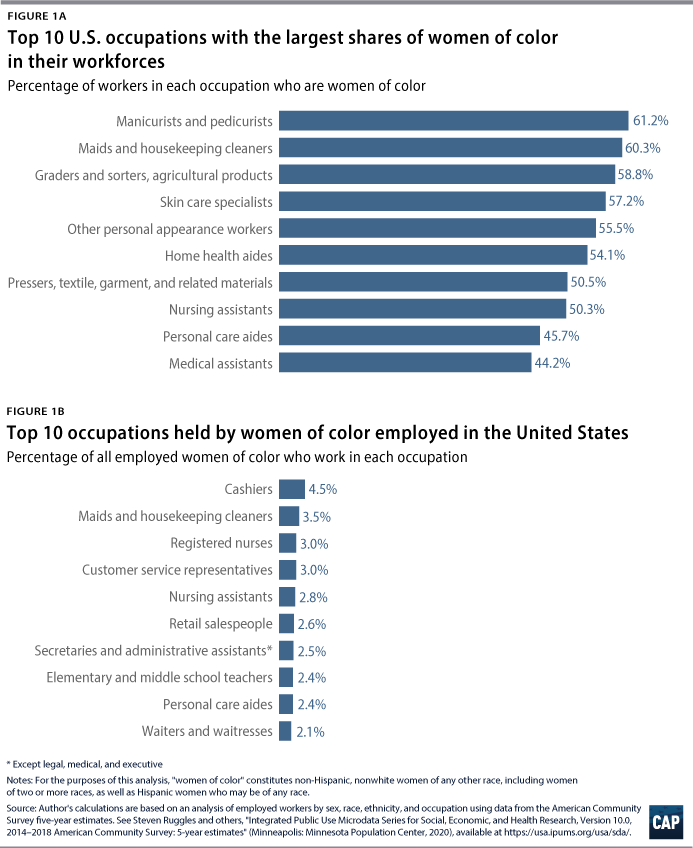

For many women of color, the current pandemic hits squarely at the crossroads where they are most vulnerable—and they face perils regardless of whether they go to work or are required to stay at home. A CAP analysis of occupational data disaggregated by race and gender shows that women of color disproportionately comprise workers in jobs such as maids and housekeeping cleaners, nursing assistants, personal care aides, and home health aides.14 (see Figure 1A) In some cases, women of color represent almost or more than half of the workers in those occupations. For example, an estimated 60.3 percent of maids and housekeepers, 50.3 percent of nursing assistants, and 45.7 percent of personal care aides are women of color.

The percentages vary for different groups of women of color. Hispanic women represent an estimated 41.6 percent of maids and housekeepers—nearly 70 percent of the women of color working in that occupation. Meanwhile, an estimated 54 percent of home health aides are women of color, with Black women comprising more than half of the women of color in these jobs. And the majority of manicurists and pedicurists are women of color, with the largest percentage comprised of Asian American and Pacific Islander women.

In addition to identifying the jobs in which women of color are disproportionately represented, it is also important to look at women of color overall and examine the jobs in which they work the most. Among all employed women of color, the largest percentage work in occupations such as cashiers, registered nurses, and elementary and middle school teachers. (see Figure 1B)

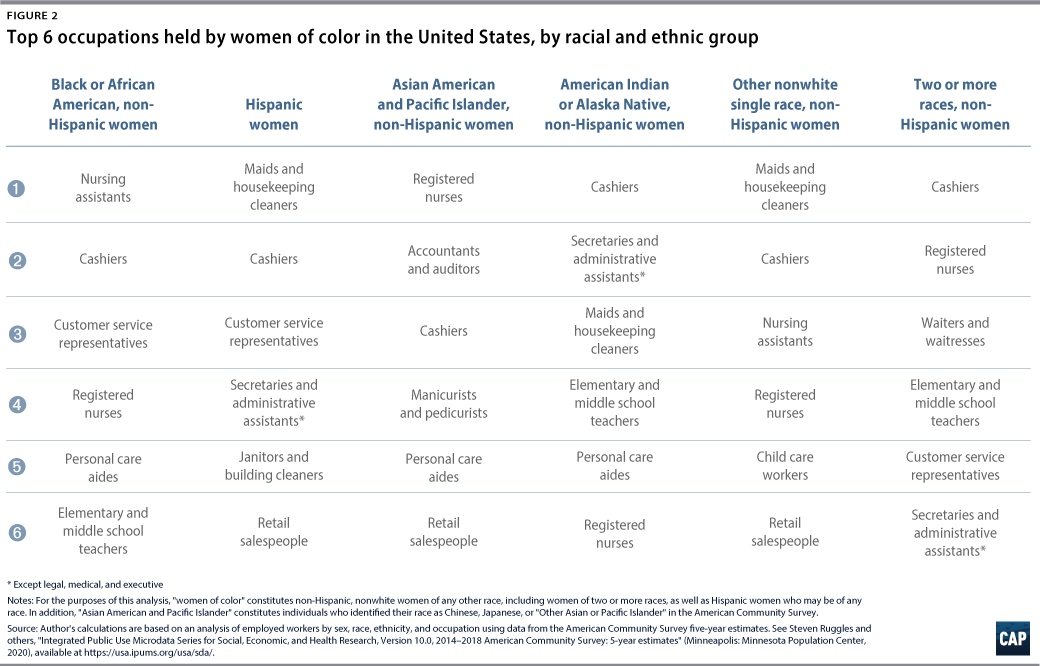

While the top jobs vary slightly when examined by racial group, there is significant overlap. (see Figure 2)

Examining the implications of the COVID-19 crisis through the lens of these women’s employment experiences raises several important concerns:

Examining the implications of the COVID-19 crisis through the lens of these women’s employment experiences raises several important concerns:

Many women of color are essential workers and at particular risk

Women of color work in jobs that place them on the frontlines of the COVID-19 crisis. Many of the top jobs in which women of color work—such as nursing assistants, home health aides, and child care workers providing emergency child care—are included in the categories of jobs deemed by many jurisdictions as essential; thus, these women are required to go to work in the face of an unprecedented crisis.15 The risks that these women face are multifaceted. Women of color working in jobs deemed essential may confront higher risks of contracting COVID-19 because of their proximity to infected individuals, infected environments, or the virus itself. And some groups may be more at risk than others. For example, nearly one-third of all nursing assistants and home health aides are Black women.16 Among early childhood workers in center- and home-based settings, nearly 40 percent are people of color—many of whom are women.17

Furthermore, because many workers in essential jobs were excluded from the emergency protections adopted in the COVID-19 relief packages that were recently signed into law, many of the health workers most directly at risk may have less access to job protections if they choose, or need, to stay home. Stories about the experiences of health workers in certain hard-hit areas reveal that a lack of access to paid sick leave has forced some to go to work even when they did not feel well.18 For the women of color who are both essential workers and single parents, the challenges are even steeper. They may need child care for longer periods of time, placing additional pressure on their family budgets, because their children are not at school. This highlights the need for emergency, affordable, quality child care.

Women of color disproportionately work in industries experiencing significant job losses

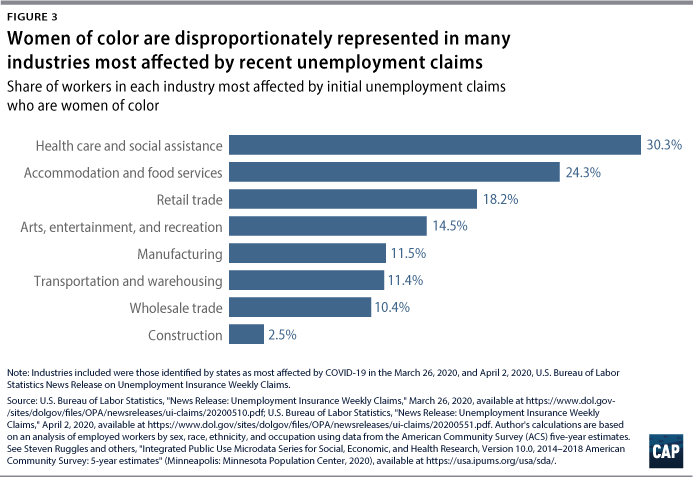

Although many women of color work in essential jobs, they also disproportionately work in several of the industries hit hardest by job losses. Recent data from the U.S. Department of Labor show that the accommodations and food services industry and the health care and social assistance industry have been among those hardest hit by severe unemployment.19 Women comprise the majority of workers in both industries: According to establishment data, they account for 53.8 percent of workers in the accommodations and food services industry and 80 percent of workers in the health and social assistance industry.20 And a separate household survey found that women of color make up a disproportionate share of workers in both industries: 24.3 percent and 30.3 percent, respectively.

Many of the women in these industries are dealing with massive layoffs and business closures, resulting in lost wages and few options to make ends meet. Even in the health care and social assistance industry, which includes many occupations that are deemed essential for public health purposes, a number of smaller facilities and social and community services may be closed or significantly reduced.21 The recently enacted Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act includes important provisions enabling workers who have lost jobs to access expanded unemployment insurance benefits, which should help them recoup lost earnings.22 However, these dollars may not be sufficient to address all of the household and health expenses that families incur during the current crisis.

Women of color disproportionately work in low-wage jobs with fewer workplace supports

Many of the jobs in which women of color work are among the lowest-paying occupations. These women are least able to afford losing any portion of their income, and they often have critical gaps in protections. Researchers have found that low-wage workers are far less likely than high-wage workers to have access to critical work supports such as paid sick days and paid family and medical leave.23 Hispanic workers, in particular, are much less likely to have access to paid time off, such as paid sick days, than other workers.24 Furthermore, among the early care and education workforce, many women of color experience larger pay gaps than their white counterparts and lack access to critical benefits such as health insurance.25 For all of these workers, the COVID-19 crisis makes their lives even more precarious, as they struggle to withstand severe economic pressures without much-needed protections.

Women of color have less mobility in jobs and wages

The disruption to employment caused by the spread of COVID-19 is likely to exacerbate long-standing challenges faced by many women of color as they navigate the labor market. Both gender and race have been shown to lessen the likelihood of moving from low-wage work to higher-paying jobs.26 Furthermore, women of color continue to be underrepresented in senior management and leadership positions when compared with white men and white women, resulting in lower earnings.27 This lack of upward and lateral mobility may make it harder for women of color to rebound from COVID-19 and find work in the future. Additionally, in some of the industries where women of color disproportionately work—such as the accommodations and food services industry—workers tend to have lower rates of job tenure, meaning that it may be harder for them to show continuous years of experience and demonstrate their ability to move up and acquire greater levels of responsibility.

This may also translate into workers with lower rates of job tenure having less access to leave and supports and less of the security and stability that come from holding the same job for a longer period of time. The accommodations and food services industry has among the lowest job tenure rates: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data on private sector employers show that in 2018, the median years of tenure with a current employer in the accommodations and food services industry was 2.1 years, compared with 3.8 years for the private sector.28 The difficulties that many women of color face moving into positions that offer better pay and greater stability also reflect the stubborn reality of the jobs that make up what is frequently referred to as the “sticky floor”—low-wage jobs that tend to have high turnover, few benefits, and limited flexibility.29

Effective responses to the current crisis must acknowledge and address these long-standing problems so that they do not simply reinforce a status quo that has held back too many women of color. It is essential that policymakers prioritize funding for employers with demonstrated success in creating advancement opportunities for women of color, as well as training programs that have proven track records of placing participants in quality jobs. Employers and programs that cannot show such positive outcomes should be prohibited from receiving COVID-19 relief funds from the federal government.

Women of color face longer spells of unemployment

Women of color frequently experience higher unemployment rates than their white counterparts. The COVID-19 crisis has led to an unprecedented escalation in unemployment: Nearly 10 million workers filed unemployment claims during the final two weeks of March 2020.30 For women of color especially, this dramatic shift may spur rapid increases in unemployment that will require longer periods of time to recover. During the recovery from the Great Recession, for example, Black women had higher rates of unemployment and longer spells of unemployment than white women.31

All of these factors collectively show how disruptions to the employment of women of color could be devastating for families that rely on their earnings to make ends meet. While some of these workers may be able to access the new paid leave protections or unemployment assistance included in the COVID-19 response legislation—the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the CARES Act32—others may be excluded because they work for businesses that are exempt from some of the laws’ requirements. Businesses with 500 or more employees are not covered by new requirements to provide eligible workers with up to 80 hours of paid sick leave and an additional 10 weeks of paid leave to care for children if their school is closed.33 Meanwhile, businesses with fewer than 50 employees are also allowed to request a similar exemption. Furthermore, even those who can access the new protections may encounter problems due to the limitations of both laws. For example, the FFCRA only provides 80 hours of paid sick leave for workers who need to stay home if they are sick or self-quarantining, which may not be adequate for workers infected with COVID-19. Although it is unclear how the current crisis will evolve over the coming weeks and months, the employment barriers that women of color frequently encounter highlight the need for longer-term interventions that could stretch for years.

COVID-19 is exacerbating the care crisis facing women of color

Given the outsize roles that many women of color play in caring for their own and other families, the earnings gaps they experience are even more significant. Like all women, women of color frequently are tasked with the primary caregiving role in their families—expected to care for family members who are sick, take family members to medical appointments, and make caregiving arrangements. Long-standing stereotypes about proper gender roles have often treated this caregiving role as all women’s personal responsibility, rather than a form of work that is as valuable as other types of work, particularly paid work performed outside of the home. These views frame caregiving as more familial and personal and have led to both unpaid and paid caregiving work—and those performing the work—being considered less valuable, less important, and, at times, less worthy of respect.34 These views affect how all women are valued as workers and are especially problematic for women of color, who are disproportionately likely to perform care-related work for pay.

These attitudes about caregiving and caregivers have deep, historical roots. During the earliest years of the United States, all women were limited in their ability to participate in the economy—often excluded from certain types of jobs by law and confined to jobs consistent with societal views about the roles and working conditions that were perceived as appropriate for women.35 For many women of color, these roles were even more narrow and devalued. From the earliest days of slavery, Black women’s labor was exploited to serve and care for white slaveholders while different waves of immigration saw Hispanic and Asian women confined to jobs as laborers, domestic workers, and farmworkers, as well as service occupations. And over the course of America’s westward expansion, Native American women faced mistreatment and a lack of economic opportunities as their communities were invaded and sapped of resources.36

Because of the combined effects of entrenched racial, gender, and ethnic biases, women of color historically have not been seen as equal to white women or men—and little consideration has been given to their personal needs and challenges. The assumption has been that they are always available to work for others and that this work should always take precedence over any personal concerns that they might have. This legacy of disrespect, devaluation, and deprioritization remains a potent undercurrent in today’s workforce landscape in which women of color disproportionately work in care-related occupations—for example, as home health aides and child care workers—without sufficient access to caregiving supports to address their own needs.

For women of color engaged in noncaregiving-related paid work outside of the home, attitudes that discourage them from taking time off or expect them to deprioritize family care obligations can make it difficult for them to respond to their own families’ needs.37 Even when women of color do have protections, some fear that taking time to address their caregiving obligations will result in negative perceptions about their commitment to their work. Research with focus groups of Black women in the state of Washington, for example, found that several were concerned about how taking time off would be perceived at work and whether it would affect their evaluations.38

Women of color are frequently caught in an economic bind, with caregiving needs that outstrip their resources. Although the cost of procuring care is high, care workers themselves are often low-paid and therefore lack economic resources. Many of the frontline workers during the coronavirus crisis, for example, may not have the additional resources necessary to afford child care. The high costs of child care relative to these workers’ overall earnings mean that they often struggle to get the care they need.39 Furthermore, because many families of color have lower overall earnings than white families, the costs associated with caregiving can quickly outstrip available resources. Researchers have found that caregiving-related costs, such as medical expenses and costs for paid care support, on average, consume a larger percentage of the overall income of many families of color than white families.40 Hispanic families and Black families engaged in family caregiving are estimated to spend 44 percent and 34 percent, respectively, of their annual income on caregiving expenses, compared with 14 percent for white families and 9 percent for Asian families.41 As already noted, the new COVID-19 response laws may offer some immediate protections for some women of color, but many women are not able to fall back on the long-term resources that may be necessary to completely address their family needs.

COVID-19 is exacerbating the discriminatory workplace barriers women of color face

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates the fact that many women of color already must navigate different biases in the workplace that affect their ability to find, retain, and succeed in a job. Even though important gains have been made over the years, discrimination is still a reality that limits opportunities for women of color and hinders their progress up the career ladder.

For years, women of color have faced challenges related to persistent wage disparities and a lack of senior management opportunities—and they continue to face these challenges today.42 Furthermore, some of the industries in which women of color are more likely to work have been shown to have higher rates of discrimination claims. CAP research analyzing unpublished 2016 data on sexual harassment charges filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found higher numbers of charges in several industries in which women of color disproportionately work, including accommodations and food services, retail trade, and health care and social assistance.43 Moreover, data released by the EEOC analyzing pregnancy discrimination charge filings from 2013 found that many of the charges were filed by women in low-wage jobs, with the majority being filed in industries such as health care and social assistance, retail trade, and accommodations and food services.44 Taken collectively, these data make clear the importance of robustly enforcing anti-discrimination protections and making workplaces free of discrimination so that women of color can have the best chance at success. The current environment of heightened uncertainty in the labor market and anxiety among workers only increases the need for strong, proactive enforcement efforts to combat discriminatory practices.

Long-standing health disparities may put women of color at higher risk of COVID-19

Access to quality health care has important cost implications for women of color and their families. Although data are limited, there are early indications of racial differences in COVID-19 infection and death rates. For instance, data collected in Wisconsin and Michigan show disproportionately higher shares of Black residents dying from the virus in those states.45 Experts suggest that these developments may be due to long-standing racial health disparities that have resulted in higher rates of disease such as diabetes and hypertension, both of which can make individuals more vulnerable to COVID-19.46

For women of color specifically, an emerging body of research has drawn attention to systemic biases in the health care system that lead to doctors and other health professionals too often dismissing or ignoring the symptoms of women of color, minimizing the pain they are experiencing, and misdiagnosing serious diseases.47 These biases, which reflect the persistent presence of racism and sexism, have led to maternal health disparities and uneven access to reproductive health care.

In the current crisis, it is essential to ensure that women of color have access to the health care services they need in order to ensure accurate, efficient, and comprehensive diagnoses and health interventions. Costs associated with this care—from access to testing to protective equipment, available drug treatments, and participation in health trials—must be covered by federal funding supports, and there must be adequate, continuous oversight to identify disparities in treatment and outcomes.

Policymakers must prioritize seven steps to ensure that policy interventions related to the coronavirus are responsive to the challenges facing women of color.

1. Expand work-family policy and caregiving protections

It is essential to ensure that all workers, including women of color, have access to work-family protections, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers should have the ability to take off the time that they need to recover when they are sick and to care for their families. Federal policymakers can provide these supports by building on the policies adopted in the recently enacted COVID-19 laws. New measures should provide comprehensive paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave, with expansions to provide low-income workers with full wage replacement and extend coverage to workers currently excluded, including the many workers deemed essential, as well as those employed by large and small business. Federal subsidies should also be available for small businesses as needed in order to assist them with the implementation of these provisions. Furthermore, any new steps that are taken should make clear that workers cannot be discriminated against or denied job opportunities because they have caregiving responsibilities.

2. Provide necessary supports for essential workers

In addition to work-family protections, it is vital that policymakers ensure that workers on the frontlines of the COVID-19 crisis have access to the full range of supports that they need. This requires not only ensuring that workers have the proper protective equipment, which is critical, but also providing them with key services, such as emergency child care and housing, that enable them to go to work without putting their families at risk. Future relief packages should include funding to bolster the availability of such services and to provide essential workers with stipends or other targeted funds that could be used toward emergency expenses.

3. Increase wages and undertake measures to decrease the wealth gap

Many women of color affected by COVID-19 work in low-wage occupations and industries, and it is critical to minimize their earnings losses as much as possible. Policymakers should take steps both to raise their normal earnings and to provide for additional income in order to respond to unique challenges created by the current emergency. Subsidies provided to employers to help keep their businesses afloat should also be used to increase wages, consistent with policy proposals such as increasing the minimum wage and eliminating subminimum wages for workers who rely on tips as well as workers with disabilities. Workers in jobs that are hazardous or that pose greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 should be able to access targeted services and interventions in order to make their workplaces safer; they should also receive additional compensation beyond their regular earnings to maximize the support they receive. As already noted, low-wage workers who are eligible for paid leave should receive full wage replacement when they take time off, rather than the partial payments currently authorized under the COVID-19 relief laws. Additional policies should include investments in programs aimed at increasing homeownership and financial literacy in order to improve the financial stability and long-term security of women of color.

4. Vigorously enforce anti-discrimination and other worker protections

Combating discrimination is critical to ensuring that women of color are treated fairly, particularly in the context of a crisis that may call for extensive absences from work. Women of color must be able to take the time that they need to care for themselves or their families without fear of retribution or negative effects on future job opportunities. Enforcement officials must take steps to guard against workers being targeted for discrimination such as sexual harassment because they are perceived to be more vulnerable or in a precarious employment situation.

It is also important for Congress and the administration to provide additional resources to help federal enforcement agencies prioritize and expand their efforts to ensure compliance with all relevant laws, especially anti-discrimination and other worker protections, rather than taking a hands-off approach in a fast-changing environment. These efforts should include an intentional focus on disparities broken down by race, ethnicity, and gender in order to pinpoint intersectional claims—claims involving the combined effects of multiple biases such as race and gender. This would help to determine whether certain groups are being excluded from job opportunities or targeted for adverse employment actions. Agencies should also consider the creation of an interagency “strike force” that could work across multiple agencies to coordinate and monitor enforcement efforts and identify specific problems in real time.

5. Institute industry-focused accountability measures

Several industries in which women of color disproportionately work have been front and center during the COVID-19 crisis. It is important to ensure accountability and transparency so that workers are treated fairly and have access to the supports that they need. Federal enforcement officials should explore ways to push industrywide initiatives to, for example, increase the number of women of color in higher-level jobs and conduct equity assessments and research evaluating promotion and attrition rates of women of color. To the extent employers receive emergency funding or loans, there should be substantial oversight and monitoring, by relevant agencies, of how the money is used in order to ensure that resources are not being used in a discriminatory manner. These efforts can include tracking any disparities in hiring, layoffs, and other employment actions and reporting findings of discrimination and settlements of employment discrimination complaints related to the COVID-19 response efforts.

6. Collect comprehensive data on COVID-19 infection and death rates

Policymakers must take steps to ensure comprehensive tracking of data on COVID-19 infections and deaths by federal, state, and local public health officials in order to determine trends, potential causes, and services that should be targeted.48 These data must be disaggregated to show impacts broken down by race, ethnicity, gender, disability status, and other factors. At the same time, strong privacy protections must be put in place to limit potential misuse of any data collected and to prohibit the sharing of such data beyond designated health officials.

7. Provide wider access to employment and training programs

Women of color and other workers displaced by COVID-19 should have access to high-quality employment and training programs with demonstrated records of success. Conversely, programs without strong records of success should be prohibited from receiving COVID-19 relief funds.