Introduction and summary

The Trump administration has weaponized immigration policy. Moreover, the president’s own words have consistently insulted and demonized immigrants of color.1 These actions make clear who the administration deems valuable, deserving of respect, and worthy of compassion—and who can be discarded or ignored. This judgment about value and worth is starkly reflected in the administration’s treatment of immigrant women and girls, particularly those in immigration custody. Their stories of mistreatment and countless indignities show the harsh intersections of administration policies to cast immigrants—particularly immigrants of color—as undesirables undeserving of entry or humane treatment and to systematically erode women’s rights, particularly access to reproductive health care.

Lost in the heated public debate about immigration are the stories of individuals who suffer under the cruelty of the Trump administration—such as Teresa, whose story is detailed in a letter to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) from several immigrant rights organizations. Teresa was four months pregnant when she arrived at the San Ysidro Port of Entry on the U.S.-Mexico border in 2017 seeking asylum from El Salvador. She was placed in a holding cell for 24 hours, where she experienced pain and heavy bleeding. She told immigration officials multiple times that she was pregnant and bleeding, and her repeated requests for medical help were ignored. Next, she was transferred to Otay Mesa Detention Center, where she met with medical staff, but she was not transferred to a hospital for treatment. Only days later did detention staff confirm that Teresa had miscarried. Following her miscarriage, Teresa had serious complications, including heavy bleeding, weight loss, and headaches. Despite being told she would be given an appointment with a provider outside the detention center, Teresa was not, and she had to pay for medications from the facility’s commissary, which were later confiscated. Multiple requests to be released from detention for humanitarian reasons were denied, and four months after her miscarriage, Teresa was still in detention, still in pain, and still neglected by medical staff.2

Teresa suffered at the hands of an immigration detention system that has dehumanized, criminalized, and abused immigrant people of color—particularly Black, Latinx, and Muslim women—and rendered their experiences invisible and irrelevant. Although the abuses of the U.S. immigration detention system are systemic and long-standing, the Trump administration has greatly escalated this cruelty.

The administration’s anti-immigrant agenda, grounded in a white supremacist and misogynistic worldview, normalizes the dehumanization of immigrant women of color. From family separation, to attempts to erode asylum protections for families and domestic violence survivors, to inaction on reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act, immigrant women live at the crux of the Trump administration’s anti-women and anti-immigrant agendas.

The administration’s attacks on women’s autonomy and access to reproductive health care are perhaps most acutely inflicted on women in immigration detention, as immigration detention has proven to be a barrier to reproductive justice. Reproductive justice, a human rights framework created by Black women activists and scholars in 1994, encompasses the ability to decide if, when, and how to have children and to live in environments that allow for parenting with dignity.3 By denying freedom and bodily autonomy, the carceral system is fundamentally incompatible with these principles. The immigration detention system separates mothers from their families, denying them the ability to parent; it mistreats pregnant people and denies access to abortion and other reproductive health care, interfering with the rights of detained people to control their reproductive lives and have healthy and positive pregnancy outcomes. Much like other abuses in the broader United States, abuses of women’s health and rights in immigration detention fall hardest on women of color, women with disabilities, low-income women, transgender women, and young women and girls.

At its core, all detention is separation—from family, from community, and from access to critical services. While the Trump administration has enacted particularly cruel policies, the rights abuses and denial of critical services faced by women and girls in immigration detention are systemic and transcend any one administration. In their current form, immigration detention centers are not only incapable of providing adequate women’s health care, but they also inflict damage on the health of women and girls by denying services, neglecting medical needs, and creating new trauma.

This report details three areas critical to the health of women and girls where some of the most egregious rights violations have occurred in immigration detention: maternal health, reproductive autonomy, and mental health. In each of these critical areas, the author offers policy recommendations to improve the standards and quality of women’s health, some of which have been proposed in existing legislation, particularly the Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act; the Stop Shackling and Detaining Pregnant Women Act; and reproductive health legislation, including the Equal Access to Abortion Coverage in Health Insurance (EACH Woman) Act and the Women’s Health Protection Act, among others.4 The report is certainly not exhaustive; in particular, it does not fully address the unique challenges faced by transgender and nonbinary people who also need to access reproductive health care while in detention. Some issues, such as the epidemic of sexual assault in immigration detention, are not given an exhaustive review, but the author provides a snapshot of the problem along with policy remedies.

The report highlights the need for policies and oversight to limit the use of detention and ensure that the rights and autonomy of women and girls in detention are not further violated. A fair, humane immigration system would use evidence-based standards of care, strong accountability measures, and a drastically limited scope of detention to protect the health and rights of women and girls in its custody. The United States’ overreliance on detention is unnecessary and is symptomatic of the criminalization and abuse of immigrants. In its place, community-based alternatives to detention can connect people with key legal, health, and social services; improve compliance with immigration proceedings; and are significantly less expensive than detention.5 Maintaining the status quo of unnecessarily detaining vulnerable groups in substandard conditions will have disastrous consequences for the health of immigrant women and girls and will facilitate the Trump administration’s efforts to dehumanize immigrant women of color.

Women and girls in the U.S. immigration detention system

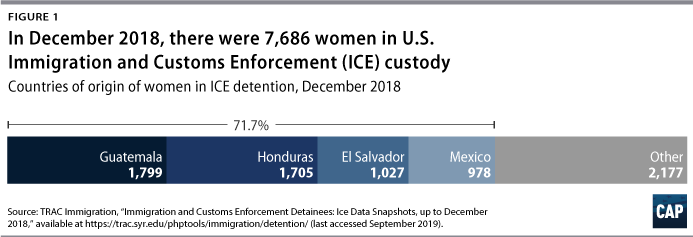

Women and girls in immigration detention have diverse backgrounds and immigration histories. The majority today are originally from Mexico and the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.6 A significant number are recently arrived asylum seekers, yet many have lived in the United States for years, if not decades, and may be undocumented or have had a change in immigration status that prompted their detention.7 Those who win relief from deportation may be granted asylee status, green cards, or other stays of deportation based on danger in their countries of origin, family ties, or time in the United States, among other forms of relief.8

The immigration detention system is expansive and complex, which poses challenges for the people navigating it from within as well as for those attempting to understand the scope of immigration custody for women and girls. People can be detained in a variety of types of facilities, from temporary shelters to county jails to private prisons, and are often transferred between facilities across the country. These facilities are largely in remote areas,9 far from access to legal and health services as well as the support of family and community. Immigration agencies, particularly U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), notoriously lack transparency around detention statistics. Without a clear picture of who is being detained, where, and for how long, it is difficult to accurately assess the breadth of the issues in detention and clearly identify the needs of detained immigrants.

In spite of the lack of comprehensive data, a handful of important facts are known about women and girls in immigration custody. The number of women detained and the proportion of women in detention are on the rise: Women and girls made up 14.5 percent of the population detained by ICE in 2016, a 60 percent increase from 2009.10 The amount of time people spend in detention has also increased. For those detained by ICE, the average lengths of detention in fiscal years 2015 and 2016 were 21 days and 22 days, respectively.11 In FY 2018, the average jumped to 39.4 days.12 For people picked up in interior enforcement actions—as opposed to those arriving at a border—the average length of stay was 53.9 days; many people are detained for months or years while waiting for their cases to be resolved.13 For children in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), the average length of stay in FY 2018 was 60 days, nearly double the average from FY 2015.14

Despite the growing numbers of women and girls in immigration custody for longer periods of time, immigration facilities have not stepped up to meet even the basic health care needs of the people in their custody, including primary care, preventive services, and emergency medical services.15 Women and girls are some of the most vulnerable people in the U.S. immigration system, with unique mental health and reproductive health needs and having often experienced trauma and gender-based violence. The detention system fails them by neglecting their health care and inflicting further damage upon their health and well-being. When seeking to identify violations of women’s health and rights in immigration detention, it is necessary to understand who the women and girls in detention are, where they are detained, and the systems that they confront when trying to access health care—including preventive and wellness services, reproductive health care, mental health care, disease and pain management, and prescription medications.

Where women and girls are detained

Women and girls are primarily detained by two federal agencies: most are in the custody of ICE, which detains adults and families, and the ORR, which has custody of minors who arrive in the United States unaccompanied, are separated from their families, or are detained while living in the United States. A smaller number of women and girls are held in the custody of CBP and the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS), although this number increased with the implementation of the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy and the humanitarian crisis at the southwest border.16 Moreover, women and girls may spend time in the custody of more than one of these agencies throughout their immigration proceedings, depending on the circumstances of their detention and arrival in the United States.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

According to its website, ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “manages and oversees the nation’s civil immigration detention system.”17 As of June 2019, ICE oversaw 214 detention facilities, 163 of which detain women.18 Twenty-six of the detention centers holding women are ICE-dedicated facilities—facilities that are used exclusively for immigration detention—with two facilities holding exclusively women. Women in the remaining 137 facilities are detained in nondedicated facilities, which are often local or county jails that contract with ICE to rent bed space.19 In 2017, more than 70 percent of people in ICE detention were in facilities run by private companies.20 Two of the facilities that detain women are family detention centers, where family units of adults and children are detained together, often after arriving seeking asylum.21 Transgender women are detained in 17 facilities, four of which are all-male facilities; the other 13 facilities have a mix of male and female populations, and only one facility has a dedicated pod to house transgender women.22 ICE often arbitrarily transfers people between facilities with no clear reasoning, which results in people being moved farther away from their families and legal services. However, no matter where a person is detained or what type of facility they are in, there should not be variations in standards or the quality of care they receive.

In FY 1994, ICE’s average daily population (ADP) was 6,785.23 By FY 2007, the ADP had drastically grown to more than 30,000, and in FY 2018, the ADP was 39,322.24 The current fiscal year appears set to reach an all-time high: As of September 21, 2019, the FY 2019 ADP was 50,136.25 Through the same date, ICE had detained a total of 503,488 people in FY 2019, already far surpassing the FY 2018 total of 396,448 people.26

The detention bed quota

From 2009 to 2017, a provision was included in the congressional appropriations language governing the funding for ICE that required the agency to maintain a minimum of 34,000 beds in detention facilities.27 Immigration advocates targeted this policy, which was known as the detention bed quota, because it artificially maintained a vast scale of immigration detention across the country.28 In 2017, the bed quota was pulled from appropriations language, but the number of people in immigration detention has stayed well above 34,000.29 In addition, the FY 2019 budget deal includes guidance for ICE to reduce the number of people in detention to around 40,000 by the end of the fiscal year, which it clearly has not done.30

Office of Refugee Resettlement

The ORR is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families and has been responsible for the Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) Program since 2003.31 In September 2019, HHS reported approximately 170 facilities with custody of immigrant children.32 ORR facilities hold children at three different levels, rising in restrictiveness: shelters, staff-secure facilities, and secure facilities.33 Congress directs HHS to place children “in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child.”34 Most children are housed at the shelter level, or in foster care, group homes, residential treatment centers, and other special needs care facilities.35 Secure facilities are essentially—and often literally—jails or juvenile detention centers. According to ORR standards, minors may be placed in secure facilities if they have been charged or could be charged with a criminal offense or are “a danger to self or others”;36 this standard often includes minors who have been suspected of gang activity, whether or not officials prove the accusation has merit.

The number of children in ORR custody has escalated in recent years; in FY 2018, 49,100 children were referred to ORR custody, compared with 13,625 in FY 2012.37 As of August 2019, 67,100 minors were referred to the ORR in FY 2019.38 In FY 2018, the average length of stay was 60 days, nearly double the FY 2015 average of 34 days; this is due at least in part to HHS’ agreement with DHS to share information about the immigration status of sponsors, which deters potential sponsors from coming forward to take children out of ORR custody.39 In recent years, around 30 percent of children in ORR custody have been girls.40 As of the end of June 2019, HHS reported an average of 13,027 children in custody, 4,377—more than 33 percent—of whom were girls.41

Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Marshals Service

Immigrants who enter the United States at the southwest border and either present themselves to or are apprehended by immigration officials are initially held in custody by CBP.42 Per CBP policy, immigrants are not meant to be held in CBP custody for more than 72 hours before release or transfer to ICE or the ORR.43 However, under the Trump administration’s increased detention efforts and mismanagement of border operations, immigrants have been held in CBP custody for long periods of time in facilities unequipped for extended living, without access to services and in horrific, overcrowded conditions.44 A July 2019 management alert from the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) warns against these dangerous conditions, which included 88 men being held in a cell with a maximum capacity of 41 people; 31 percent of minors being held for longer than 72 hours, including children under 7 years old; and lack of access to showers, meals, and clean clothing, among other violations of standards.45

Immigrants who enter the United States without authorization can be referred for federal criminal prosecution; under the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy, this practice greatly increased and particularly targeted parents traveling with minor children.46 When immigrants are criminally prosecuted for crossing the border, they are detained in federal criminal facilities, which are not permitted to detain children. This meant that thousands of children were separated from their parents before the zero tolerance policy effectively ended in June 2018.47 Those who are referred for criminal prosecution enter the custody of the USMS, which controls the custody and transport of people arrested by federal agencies.48 The USMS is also responsible for transporting immigrants detained by CBP to ICE custody and to court hearings.49 As of March 2018, more than 20,000 immigrants were in USMS custody.50

Health care standards

Once they enter an immigration detention center, women and girls seeking health care such as preventive care, pain management, reproductive health care, and mental health care must contend with a patchwork of policies, understaffed medical teams, and often indifferent or abusive officials. Understanding the landscape of health care standards governing immigration detention facilities is important in assessing where those standards fall short of the health care needs of detained women and girls and identifying when facilities violate the standards and cause harm.

The existing guidance on both general health services and women-specific services across immigration detention facilities in the United States varies widely. What remains consistent, however, is the poor quality of care that many people in detention, and women in particular, typically receive. As explored throughout this report, the presence of health care services—including critical preventive services—is minimal. Instead, detention facility staff often ignore medical issues until they rise to the level of emergencies. In addition to the harm caused by inadequate and often negligent provision of health services, the conditions of immigration detention itself are damaging to the physical and mental health of people in custody.

The most up-to-date standards guiding the provision of health care for detained immigrants are the ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) 2011, which were revised and updated in December 2016, and the “ORR Guide: Children Entering the United States Unaccompanied.” The PBNDS 2011 are the first health care standards requiring ICE to specifically address women’s medical care.51 ICE also has various directives for the ICE Health Service Corps, which provides or oversees health care in detention facilities, including around emergency contraception and care for transgender people.52

Included in the section focused on women’s health in the PBNDS 2011 are an initial health assessment; pregnancy services and counseling regardless of desired pregnancy outcome, including abortion care; access to contraception; preventive care such as breast exams, Pap smears, and testing for sexually transmitted infections; and pregnancy-specific mental health services.53 Other sections of the PBNDS 2011 include protections and procedures for survivors of sexual abuse, HIV treatment, continued access to hormone treatment for transgender people, and a mental health program, among other guidelines.54 The ORR guide does not provide as much detail about reproductive health standards but does require providing comprehensive information about and access to family planning and reproductive health services, care plans for pregnant or parenting minors, access to mental health services, and policies around sexual abuse and specific guidance for LGBTQ minors.55

Despite the presence of these standards, the most recent guidance does not apply across all ICE facilities; instead, ICE facilities operate under a range of health care standards. Dedicated ICE facilities generally use one of two standards: the PBNDS 2011, or the Family Residential Standards from 2007,56 which apply to facilities holding families including adults and children together. Nondedicated facilities operate under a wider and inconsistent range of standards: the PBNDS 2011, as well as the older and more outdated PBNDS 2008, and the 2000 National Detention Standards; these older standards include less specific and comprehensive guidance, and they particularly lack information specific to women’s health care.57 According to analysis from the National Immigrant Justice Center, only about 20 percent of ICE facilities operate under the most up-to-date PBNDS 2011.58 In addition, only 65 percent of adult detention centers are actually contractually bound by one of these sets of standards.59 Due to the fact that nondedicated facilities often exist within criminal jails and prisons, there may also be confusion and conflict between ICE standards and the standards of the local facilities.

In addition to lacking consistent, quality standards, for those facilities that are required to follow ICE health standards, the agency has failed to enforce existing standards and penalize facilities that violate them. A report from the DHS OIG found that between October 2015 and June 2018, ICE only imposed two financial penalties, “despite documenting thousands of instances of the facilities’ failures to comply with detention standards.”60 Instead, ICE regularly issues waivers for health and safety standards that allow facilities to violate standards with no consequences.61

CBP and the USMS also each have their own standards for medical care in their detention facilities. The USMS uses the Prisoner Health Care Standards, which include an extensive list of services not covered, including many reproductive health services.62 CBP operates under the National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS), from October 2015.63 These standards contain extremely limited guidance on and scope of medical care. In January 2019, in response to an influx of immigrants held for extended periods of time in CBP custody on the southwest border, DHS issued a directive to enhance medical efforts.64

Example: Different standards in practice

Without consistent, binding, evidence-based standards for health care, the services that a person receives may depend entirely on where they are detained and may vary as they are transferred between facilities. A pregnant woman who enters immigration custody could be treated very differently across different facilities, even if she received all of the care listed in a particular standard. For example:

- She could first be detained by CBP, where standards say that she should not be given an X-ray search and that she should be given a snack upon arrival and meals every six hours, with regular access to snacks.65 There would be no further guidance as to her medical care, and she may not receive any health screening.

- She may then be transferred to an ICE facility that operates under the PBNDS 2008. There, she would have access to pregnancy testing and services, including routine prenatal care, addiction management, comprehensive counseling on pregnancy options—although there is no specific mention of abortion—nutrition, and postpartum follow-up care.66

- She could then be transferred to another facility, this time operating under the more up-to-date PBNDS 2011. In addition to the services covered under the PBNDS 2008, the standards in the new facility would also give her access to specialized prenatal care, lactation services, and abortion care. However, if she were transferred between facilities in fewer than 12 hours, she may not receive a preliminary health screening for days after entering DHS custody.67

- After another transfer, she could be placed in a facility governed by the 2000 National Detention Standards. The facility’s only guidance would be to notify the officer in charge in writing that she is pregnant.68 She could lose access to all the care she was previously receiving.

In addition to following the ORR guide, all federal agencies holding minors are bound by the 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement. The Flores settlement set national standards for the safety and treatment of children in federal custody, including an emphasis on reuniting children and families as quickly as possible and a requirement to place children “in the least restrictive setting appropriate.”69 While the Trump administration has attempted to undermine the Flores settlement and detain children and families indefinitely, its efforts have been blocked in the courts.70

In addition to these standards, ICE and the ORR have protocols under the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), to prevent, detect, and respond to sexual abuse and assault in detention, including medical care.71 PREA was passed in 2003, but HHS and ICE were not directed to create PREA standards until the passage of the 2013 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act. However, HHS’ standards contain a religious exemption that could allow grantees and contractors to deny the provision of comprehensive reproductive health care or care for LGBTQ survivors if they claim a moral or religious objection.72

International human rights standards recognize “[t]he right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”73 As outlined by the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and the World Health Organization, the right to health includes, among other things, entitlements to prevention, treatment, and control of diseases; access to essential medicines; equal and timely access to basic health services; and maternal, child, and reproductive health.74 This report will demonstrate that the standards governing health care in immigration detention facilities are insufficient, inconsistent, and unevenly applied. Where standards do exist, they are regularly violated, amounting to egregious violations of the human right to health, particularly for women and other vulnerable groups.

Maternal health: Inadequate care, inhumane practices

In February 2019, a 24-year-old woman who was six months pregnant went into premature labor and had a stillbirth four days after being detained in Texas.75 Another woman, Olivia, a 24-year-old detained at seven months pregnant, was shackled, experienced severe pain for days that was ignored or dismissed, and was neglected for hours when she went into premature labor, ultimately delivering a baby with numerous serious medical issues.76 Esther Ramos was detained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the Office of Refugee Resettlement when she was 16 years old and two months pregnant, and while in ORR custody she lost 20 pounds, often only received two meals per day, was denied rest, and had minimal medical care.77 E was 23 years old and four months pregnant when she was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement after arriving in the United States seeking asylum.78 She received no pregnancy-related services, and two weeks later, she was denied medical care by detention officials as she miscarried. She decided to return to El Salvador after her miscarriage, when she realized that the United States would not be a safe haven for her.79

From October 1, 2017, to August 31, 2018, ICE detained a reported 1,655 pregnant women.80 As of August 31, 2018—the most recent data available—there were 60 pregnant women in ICE custody.81 News outlets and advocates have reported stories of pregnant women across ICE, CBP, and U.S. Marshals Service custody who faced abuse and neglect, from being shackled across the belly, arms, and legs; to having requests for medical attention ignored; to a complete lack of medical care during pregnancy and miscarriages.82 Between fiscal years 2017 and 2018, a reported 28 women had miscarriages in ICE custody.83

As will be discussed in more detail later in this report, detention is a source of stress and trauma, particularly for those who have experienced past trauma. It is well-understood that maternal stress and perinatal mood disorders can lead to negative health outcomes for both mothers and infants.84 Perinatal mood disorders, including maternal depression, are linked to hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes, all risk factors for maternal mortality and morbidity.85 There is also a well-documented association between maternal stress and higher risk of preterm birth, although the reasons for this link are not entirely clear.86 Incarceration and fear over immigration status can be serious stressors for pregnant women.87 One study found that worry about deportation was associated with high blood pressure and risk for cardiovascular disease in women,88 and immigration detention has proved to be detrimental to mental health across numerous studies.89

The negative impact of immigration detention for pregnant women, even in the best circumstances, would be significant. Yet the U.S. immigration detention system is nowhere near providing the best circumstances. Moreover, on top of these baseline stressors, detained pregnant women are experiencing at best inadequate maternal health care and at worst outright abuse.

Standards for detention of pregnant people

In September 2017, seven organizations—including the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Immigration Lawyers Association, the American Immigration Council, the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, the Women’s Refugee Commission, the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies, and the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project—filed a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) on behalf of pregnant women detained by ICE.90 The complaint notes the inconsistency in the health care standards that apply to detained pregnant women, including the Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 and 2008, the Family Residential Standards, and the 2000 National Detention Standards. The organizations detail examples in which detained pregnant women were treated in violation of ICE’s health care standards, legal obligations, and “accepted medical standards and practices concerning pregnant women.”91 Their accounts include having requests for care ignored or delayed, substandard quality of care, and mismanagement of miscarriage, as well as an overarching concern that the traumatic experience of detention itself harmed pregnancies.

Quality care for pregnant people includes many components, as outlined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).92 Perinatal care should be patient-centered, culturally and linguistically appropriate, focused on assessing risk, and begin with preconception care—comprehensive primary and reproductive health care before pregnancy. The ACOG and AAP guidelines outline basic perinatal care, which includes: physical examinations, routine laboratory assessments, assessment of gestational age and normal progress of pregnancy, ongoing identification of risk, psychosocial support, childbirth education, and care coordination.93 Specialty care includes all elements of basic care in addition to fetal diagnostic testing and management of medical and obstetric complications.94 Typical prenatal care visits for a low-risk pregnancy should occur every four to six weeks for the first 32 weeks, every two to three weeks until the 37th week, and weekly until delivery.95

The PBNDS 2011 section on women’s health care contains standards that pregnant women in custody “have access to pregnancy services including routine or specialized prenatal care, pregnancy testing, comprehensive counseling and assistance, postpartum follow up, lactation services and abortion services.”96 Medical providers are directed to identify the specific needs of a pregnant woman and inform detention staff of those particular needs, including diet and housing. Those with high-needs pregnancies must be referred to a specialist, and all pregnant women in detention must be closely supervised by medical staff. The standards also require providing counseling to pregnant women in detention “in keeping with their express desires in planning for their pregnancy,” including abortion, continuing a pregnancy, and adoption.97 After a person gives birth, miscarries, or has an abortion, they are supposed to have a mental health assessment within 45 days.98

In theory, these standards lay the groundwork for the provision of fairly comprehensive services for pregnant people in detention. Yet the CRCL complaint, as well as numerous news reports, demonstrate that violating these standards is the norm, and that if care is provided at all, it falls far short of these standards.99 In addition, the variety in health care standards governing detention centers means that many facilities use outdated guidance, setting the bar for care even lower. Finally, ICE standards and directives use the term “pregnant women” rather than “pregnant people,” which excludes the needs and experiences of pregnant people who may not identify as women.

In December 2017, shortly after the CRCL complaint, ICE privately instituted a new policy around the detention of pregnant immigrants.100 The policy reversed an August 2016 directive known as “presumption of release,” whereby if a pregnant woman was not subject to mandatory detention under immigration law, she would generally not be detained, except in “extraordinary circumstances.”101 The policy change, which was not made public until March 2018, also limits reporting requirements that allowed for monitoring the treatment of pregnant women by removing requirements for centralized and up-to-date tracking of all pregnant people in detention by the ICE Health Service Corps headquarters.102 In FY 2018, from October 2017 through August 2018, 18 women may have miscarried in ICE custody.103 In the previous fiscal year, before the new policy of detaining pregnant women went into effect, ICE reported 10 miscarriages in detention.104

Along with more than 250 reproductive, civil, and human rights organizations, many organizations of medical providers expressed their opposition to the change in policy, including the ACOG, the AAP, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.105 In an April 2018 letter to the acting director of ICE, they state:

All pregnant women and adolescents held in federal custody, regardless of immigration status, should have access to adequate, timely, evidence-based, and comprehensive health care. Pregnant immigrant women and adolescents should have access to high levels of care, care that is not available in these facilities.106

The organizations note that although ICE standards to improve access to reproductive health care exist, adherence to the standards across facilities is unknown, and the detention of pregnant women and adolescents puts their health and the health of their pregnancies at risk.107

Shackling continues despite guidelines

The practice of shackling pregnant people is a human rights abuse that causes trauma and life-threatening health issues.108 Despite guidance from the ACOG on the physical dangers of shackling and guidance from the American Psychological Association on the mental health impacts,109 jails and prisons in 28 states, as well as immigration detention facilities nationwide, continue to use restraints on pregnant people during pregnancy, labor, and postpartum, particularly during transport.110

Much like the health care standards for pregnant people in detention, standards around shackling pregnant immigrants vary depending on the detention agency.

Current standards on shackling

The PBNDS 2011 state that for all pregnant women in ICE custody, including when in transit or at an outside medical facility, “At no time shall a pregnant detainee be restrained, absent truly extraordinary circumstances that render restraints absolutely necessary.”111 In addition, the standards prohibit all use of restraints during labor.112

CBP bars shackling of pregnant adults and minors unless they are deemed dangerous or a flight risk, and in those cases bans restraining pregnant people face-down, on their backs, or across the area of pregnancy.113 Like the PBNDS 2011, CBP standards ban all shackling during labor and limit postpartum shackling to extraordinary circumstances.114

The Family Residential Standards and 2000 National Detention Standards are weaker in their restriction of shackling.115 Rather than prohibit shackling in most cases, the standards only require that medical staff advise on the type of restraints used, are present while restraints are applied, and advise on the medical necessity of using restraints in medical facilities.116

As mentioned above, in the course of their detention, pregnant people may move between CBP, USMS, and ICE custody, and may be subject to varying regulations and practices around shackling. Not one of the standards includes a complete ban on shackling, leaving the door open for the use of restraints. Indeed, pregnant women have reported being shackled around their hands, legs, and area of their pregnancy while in ICE, CBP, and USMS custody.117

An OB-GYN who practices at a hospital in Texas reported witnessing pregnant people in USMS custody arrive to the hospital shackled around their hands, feet, and bellies, and told Rewire.News that her postpartum patients are regularly shackled.118 In one incident, the doctor intervened to prevent USMS from shackling a patient while she was in labor. Multiple staff members at clinics in El Paso have reported similar regular practices of shackling, including shortly after giving birth.119 Three women who were pregnant and detained by CBP told BuzzFeed News that they were shackled around their hands, legs, and bellies; all three had miscarriages while in custody.120

Policy recommendations

In order to ensure the health of pregnant people in the U.S. immigration system, key policy steps include eliminating the detention of pregnant people absent extraordinary circumstances—instead increasing investment in community-based alternatives to detention—and providing strong safeguards for those who remain detained.

First, Congress should reinstate the presumption of release and ban the detention of pregnant immigrants except in extraordinary circumstances. Immigration detention facilities have proved themselves incapable of providing adequate health care to pregnant people, and the stress and conditions of detention along with negligent health care have led to disastrous consequences for detained pregnant people.

Lawmakers should also ban the shackling of pregnant people in immigration custody under any circumstance. Shackling is a human rights abuse that has been demonstrated to cause both physical and psychological damage to pregnant people.121

Congress must use its oversight role to enforce health care standards for pregnant people in immigration detention and must direct agencies to implement strict health care guidelines for their treatment. In April and May 2018, Democratic senators—including Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, Nevada Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, California Sen. Kamala Harris, Illinois Sen. Richard Durbin, Delaware Sen. Tom Carper, New Hampshire Sen. Maggie Hassan, and Washington Sen. Patty Murray—sent letters to the DHS inspector general and the acting director of ICE expressing concern and requesting information on the detention and treatment of pregnant women in ICE custody.122 The letters included requests for data on pregnant people in ICE custody, including demographic information and their time spent and services received in detention; interviews with people who were pregnant while detained and medical providers; an overview of the system for monitoring pregnant people in detention; details of pregnancy and postpartum services available at each facility; and rationale for the Trump administration’s end of presumption of release.123 Continued oversight from Congress, including exploring the possibility of independent monitors, as well as the DHS Office of Inspector General and CRCL is necessary to hold detention officials accountable for the care of pregnant detained immigrants.

Reproductive autonomy: Coercive practices and rights violations

Jane Doe’s story

According to an American Civil Liberties Union complaint, Jane Doe was 17 years old when she arrived unaccompanied in the United States fleeing violence, including parental abuse in her home country. Jane, who was pregnant, was placed in a shelter in Texas, where she requested an abortion. Officials from the Office of Refugee Resettlement and the Department of Health and Human Services then allegedly began a campaign that denied Jane her reproductive autonomy and violated her constitutional right to access abortion care. Jane says these actions included: forcing her to go to a fake women’s health center that pressured her to continue her pregnancy; forcing her to have a medically unnecessary sonogram against her will; blocking her from traveling to medical visits; and telling her abusive parents, even after Jane obtained a court order allowing her to have an abortion without parental consent. When Jane was finally able to have an abortion after a drawn-out court battle, the procedure had been delayed by a month.124

The quality of reproductive health care in immigration custody is dismal and often neglectful. In addition to receiving substandard care, women and girls in immigration detention also face threats to their health and bodily autonomy through coercive, unconstitutional policies and practices.

These harmful practices continue the United States’ long history of seeking to control women’s reproduction. During slavery, Black women were routinely raped and forced to give birth to children who were then torn from them to fuel the slave labor economy.125 The eugenics movement, most popular beginning in the early 20th century, targeted people of color, immigrants, people with mental illness and other disabilities, low-income people, and others with forced sterilization and abortion.126 Racism and reproductive coercion were central to U.S. government population control efforts, particularly targeting Puerto Rican, African American, and Native American women in large-scale sterilization campaigns between the 1930s and 1970s.127 People who are incarcerated have been particular targets of sterilization campaigns, including in the present day. Between 2006 and 2010, California prisons sterilized at least 148 women without their consent.128 As recently as 2017, there have been reports of individuals being offered reduced sentences in exchange for being sterilized or using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC).129 While such programs are often presented as voluntary,130 when a person’s freedom is in the balance, there is no real choice.

Under the Trump administration, there have been numerous reports of women in immigration custody having their access to comprehensive reproductive health care, particularly abortion, restricted. While seemingly contradictory, forced sterilization and forced birth are instruments of the same goal—to exert power and control over immigrant women and deny them bodily autonomy. Interfering with immigrant women’s ability to determine their reproductive destinies—whether through eugenics and forced sterilization, the denial of abortion and maternal health services in detention, or the fact of immigration detention itself—is a denial of reproductive justice. While there have not been specific reports of forced sterilization or coercion to use LARCs in immigration detention, these practices have a historical foundation and are ongoing among incarcerated women and in immigrant communities.131 The reproductive justice framework recognizes that the conditions in a person’s community affect their bodily and reproductive autonomy.132 In immigration detention, the carceral system, misogyny, racism, and xenophobia intersect to produce a wholly inadequate system of delivering reproductive health care and to deny reproductive control to women in detention.

Abortion access for girls in ORR custody

A prime example of the reproductive coercion perpetrated in the immigration system is the denial of access to abortion care for girls in ORR custody. The Trump administration has made clear its goal to see Roe v. Wade—the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision that established the constitutionally protected right to access abortion care133—overturned and abortion outlawed in the United States, and these anti-choice efforts are being carried out throughout the federal government. One particularly pernicious site of attacks on abortion rights has been the ORR, where Scott Lloyd, an anti-abortion advocate, served as director from March 2017 to November 2018.134 While purportedly unable to keep accurate records of children forcibly separated from their parents, Lloyd had no problem tracking the menstrual cycles of young women in ORR custody as part of his efforts to strip young women of their abortion rights.135

As director of the ORR, Lloyd made it his mission to prevent girls in ORR custody from accessing their right to abortion care. Lloyd personally reviewed each request from a minor who sought abortion care and did not grant a single request; those who were able to obtain abortion care did so only after court intervention.136 He made personal visits to minors seeking abortion care and received regular updates in the form of a spreadsheet that tracked pregnant minors, including information about how far along they were in their pregnancies, whether the pregnancy was the result of consensual sex, whether they had requested abortion care, and when their last menstrual cycle occurred.137 While Lloyd no longer works at HHS, the department remains populated with anti-choice advocates, including Roger Severino, who leads HHS’ Office for Civil Rights.138

This policy of interfering with abortion access, while vigorously enforced and expanded by Lloyd, did not start with him. A 2008 directive from David Siegel, acting director of the ORR at the time, titled “Medical Services Requiring Heightened ORR Involvement,” laid the groundwork for such abuses.139 The memo states that if a minor in ORR custody seeks abortion services, the facility must immediately contact the director of the Division of Unaccompanied Children’s Services and is prohibited from taking any action without ORR approval. A March 2017 memo from Kenneth Tota, then-acting director of ORR, adds that facilities “are prohibited from taking any action that facilitates an abortion without direction and approval from the Director of ORR.”140

In October 2017, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on behalf of a pregnant minor, Jane Doe, who was in ORR custody in Texas and denied abortion care.141 The court granted a temporary order blocking the government’s interference. However, on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, a three-judge panel led by now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh sent the case back to the district court to give the ORR time to find a sponsor to transfer Jane Doe out of custody. Only after an appeal to the full D.C. Circuit Court, and weeks of delay, was Jane Doe able to exercise her constitutionally protected right to access abortion care.142

The case grew into a class action suit, J.D. v. Azar—formerly Garza v. Azar and Garza v. Hargan—on behalf of all pregnant minors in ORR custody. Documents from the case provide a disturbing look at Lloyd’s ORR, in which ORR facilities were directed to only refer young women to fake “crisis pregnancy centers” that attempted to coerce them into carrying their pregnancies to term and to deny minors the ability to seek a judicial bypass—a process in which a judge grants approval for a minor’s abortion when parental consent is not available—even when contrary to state laws.143

In June 2019, the D.C. Circuit Court ruled to uphold an injunction that prevented the government from blocking access to abortion for minors in ORR custody.144 Lloyd no longer leads ORR, and for the time being, the government is not allowed to interfere with access to abortion for minors in ORR custody. Yet the Trump administration’s obstruction and open hostility to reproductive health access for unaccompanied minors is deeply dangerous.

Impact of federal and state abortion restrictions

Women and girls in immigration detention are subject to the abortion laws of the states in which they are detained. States that detain the most immigrants, such as Texas, also have some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country.145 These varying restrictions fall particularly hard on minors seeking abortion care. Thirty-seven states have laws requiring parental involvement for minors to receive abortion care or judicial bypass if parental consent is unavailable.146 For unaccompanied minors, contacting parents may be dangerous, unwanted, or simply not possible. The additional barrier of having to go to a judge to obtain a judicial bypass while in immigration detention is extremely onerous. As the ORR actively resists complying with these laws, it can be nearly impossible. Additional state laws requiring waiting periods, mandatory ultrasounds, targeted restrictions on abortion providers that limit the number of clinics available, and gestational bans, among others, all add to the already burdensome process of accessing an abortion from immigration custody.147 A majority of people in immigration custody are detained in rural areas, which disproportionately lack access to abortion providers.148

Restrictions on funding for abortion care also push it out of reach for many in immigration custody. The Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 note that ICE will only cover the costs of an abortion in cases of rape or incest or if the life of the pregnant person is in danger, “consistent with the practice of our federal partners.”149 Since 1976, the Hyde Amendment has prohibited certain federal funds, such as Medicaid funds, from going toward abortion care, and similar and sometimes even more onerous language has been added to other federal programs that provide health coverage.150 These funding restrictions are burdensome for many, and that burden is only compounded for women and girls who are detained with no means of earning income and may not have access to outside support to fund the procedure.

The right to access abortion care established under Roe v. Wade applies to all people in the United States, including those in immigration detention.151 The combination of restrictive state and federal laws and an administration that is actively working to undermine those rights violates the reproductive autonomy and constitutional rights of people in immigration detention.

Policy recommendations

Protecting reproductive autonomy and preventing coercive actions requires actions directed toward immigration detention officials as well as broader reform of restrictive state and federal laws.

Policymakers must safeguard against state laws designed to limit access to abortion, including bans on abortion before viability, medically unnecessary requirements for clinics and patients such as mandatory ultrasounds and waiting periods, mandated counseling that is medically inaccurate, and parental consent requirements for minors.152 In addition, Congress must act to repeal the Hyde Amendment and similar insurance coverage restrictions that prevent the federal government from funding abortion care.153 Removing these restrictions would reduce the often insurmountable barriers to accessing abortion care in immigration detention. For example, most universal health care proposals have comprehensive reproductive health coverage that includes abortion coverage for people in immigration detention.154 States must also pass legislation that prohibits political interference in health care decisions for all, including those in immigration custody.

Lawmakers and federal agencies must enforce the constitutionally protected right to access abortion, including in immigration custody, and put an end to illegal interference in access to comprehensive reproductive health care, particularly for minors. Oversight bodies must work to ensure access to the full spectrum of quality, noncoercive family planning and reproductive health care in detention. These services must include contraception; treatment for HIV and sexually transmitted infections; and pregnancy-related care regardless of the outcome of pregnancy, including birth, abortion, and miscarriage.

Finally, the departments of Homeland Security and Health and Human Services must end their agreement to share information about children in ORR custody and their potential sponsors. Fiscal year 2019 appropriations law included a provision that prohibits U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in most cases from detaining or removing sponsors who are found to be undocumented based on information from HHS.155 Democratic members of the House are seeking to expand this provision to bar all information-sharing between DHS and HHS unless there is reason to believe that a potential sponsor has a history of disqualifying offenses.156 The practice of information-sharing has led to fewer sponsors coming forward for fear that they will be targeted by ICE or Customs and Border Protection.157 Without sponsors, children will stay in ORR custody for longer periods of time and may have health care needs that the ORR is not capable of providing—a September 2019 report from the HHS Office of Inspector General directly linked this policy to the prolonged custody of children, which in turn led to increased stress, anxiety, and other mental and behavioral health issues among children.158

Lack of mental health services for women at detention centers adds to their trauma

A few weeks after Dulce Rivera, a transgender woman from Honduras, was first placed in solitary confinement for disciplinary reasons, she attempted suicide. She was then placed on suicide watch, and instead of receiving compassionate mental health services, she was simply moved to a different solitary cell, this one labeled “suicide safe.” When she was transferred to a different detention center, she was once again placed in solitary confinement, this time ostensibly to protect her from potential violence in the general population. In all, Rivera spent nearly a year in solitary confinement. Now out of detention, she continues to experience disorientation, trouble sleeping, and nightmares.159

Unsurprisingly, immigration detention facilities are ill-equipped to provide mental health services. Detention centers often lack dedicated mental health professionals or are understaffed and use punitive practices against immigrants with mental health issues. Detention itself is a source of trauma with lasting impacts on the lives of women and girls, who often have experienced past abuse and trauma. No one with existing mental health issues should be placed in immigration detention absent extraordinary circumstances; instead, they should receive medical care and social services through community-based alternatives to detention. Further, detention facilities must be better equipped to support mental health needs through the robust provision of trauma-informed, gender-specific mental health services that are culturally and linguistically competent for all detained women and girls.

Detention creates and compounds trauma

Women and girls in immigration detention often bring with them histories of trauma and abuse. In particular, many who enter the United States seeking asylum flee domestic violence, sexual abuse, and gender discrimination in their home countries.160 In Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, the homicide rates for women are well above the global average and are often connected to domestic violence.161 Especially for those who arrive at the southwest border, many have confronted additional abuse on the journey to the United States.162 All of these abuses are compounded for women who experience multiple forms of bias, including LGBTQ women, indigenous women, and women with disabilities.

Upon arriving in the United States, women face further trauma at the hands of the U.S. immigration system. Even though the Trump administration officially ended its family separation policy in June 2018, women continue to be ripped from their children and girls from their parents.163 For those already living in the United States, detention is separation in and of itself, from family, from community, and from access to crucial legal and health services.

The devastating impact of family separation on both parents and children is well-documented.164 One study of adult refugees found that family separation had negative mental health consequences comparable to physical assault and torture.165 For children, exposure to the trauma of separation and detention creates toxic stress, which has both short- and long-term impacts on child development.166 Exposure to toxic stress can weaken the immune system and hinder development, leading to poor coping and stress management skills.167 Even spending a few days in detention increases the likelihood that a child will experience anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychological distress.168 In addition, separated children are being forced to care for each other, with reports of children as young as 7 years old taking care of infants.169 This may lead to what experts call “parentification,” which has been linked to short- and long-term physical and psychological distress in children, including anxiety, depression, and heart disease.170 The experiences of parents separated from children, particularly mothers, will often mirror those of their children: anxiety, depression, and lasting trauma.171

Even without family separation, detention itself is damaging to mental health. There is a unique dimension to trauma when after reaching a destination that one expects to be safe, they only find continued danger and abuse.172 A systematic review of the impact of immigration detention on mental health across 26 studies from eight countries, including more than 2,000 participants, found widespread evidence of detention’s adverse effects on mental health.173 Importantly, detention was found to independently contribute to poor mental health outcomes.174 In addition, increased duration of detention was associated with greater severity of negative mental health symptoms, and people with past trauma or mental illness were particularly negatively affected by detention.175 Women and girls are especially likely to have experienced violence and traumatic events in their home countries, including gender-based violence such as domestic violence and sexual abuse.176 Another review from Physicians for Human Rights reinforced the findings that detention negatively affects the mental health of children, adolescents, and adults.177 It noted that while longer periods of detention amplified the impacts, even short periods of detention in high-quality facilities had lasting health impacts.178

Need for trauma-informed care

Detention centers largely lack adequate mental health services to support the needs of anyone, let alone the unique needs of women and girls, who very often enter immigration custody with experiences of trauma and mental illness. Instead, detention compounds their trauma, introducing new stressors of abuse and confinement as people navigate the complex and harsh immigration system and separation from their families and communities. All people in detention, and particularly women and girls, need trauma-informed care that acknowledges their lived experiences and provides resources to support their mental well-being.

Defining trauma-informed care

As defined by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the trauma-informed model of care “emphasizes the need for behavioral health practitioners and organizations to recognize the prevalence and pervasive impact of trauma on the lives of the people they serve and develop trauma-sensitive or trauma-responsive services.”179

The Office of Refugee Resettlement does provide some guidance on trauma-informed practices for children in its custody. The ORR standards for services for minors in the Unaccompanied Alien Children Program state that care providers must be trained in “trauma-informed interviewing, assessment observation and other techniques.”180 In addition, guidelines on the use of restraints and isolation note that these practices can be traumatizing, particularly for children who have previously experienced trauma.181 The guide also directs providers to SAMHSA’s National Center for Trauma-Informed Care and Alternatives to Seclusion and Restraint, which is “dedicated to promoting alternatives to seclusion and restraint, and building the knowledge base on the implementation of trauma-informed approaches in programs, services, and systems.”182 The Department of Health and Human Service’s Administration for Children and Families also provides a resource list on trauma-informed services.183

Although the presence of these guidelines is a step in the right direction, reports of inadequate mental health services for detained children are still common. In September 2019, the HHS Office of Inspector General reported that children in ORR custody had widespread experiences of intense trauma, including in their countries of origin, on the journey to the United States, and within the United States, particularly as a result of family separation.184 Mental health clinicians in these facilities reported feeling unprepared for the level of trauma that many children experienced and an inability to adequately address the mental health needs of the children in their custody.185 Protection and advocacy agencies that monitor detention conditions for people with disabilities including mental illness have observed children with “behavioral issues” or additional mental health needs being transferred to more restrictive facilities, rather than receiving proper mental health services.186 Concerns around informed consent and coercive medical practices for minors separated from adult family members are also prevalent in detention.187 Advocates, doctors, and former employees at ORR shelters have reported insufficient numbers of counselors for detained children, as well as overmedication of children in custody; in some instances, staff medicate children who act out, at times without their consent, rather than use therapy or other behavioral methods.188

For adults in the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, there is minimal access to any mental health services, let alone trauma-informed care. A 2017 Human Rights Watch report documented instances of severe understaffing of mental health professionals in detention centers and inadequate treatment for serious diagnoses such as post-traumatic stress disorder or major depressive disorder, including only limited check-ins with providers and medication.189 Detained immigrants with mental illness are often placed in isolation and face punitive measures for behaviors related to their often untreated mental illness.190

In addition to immigration detention, incarcerated women in the criminal justice system have extremely high rates of mental illness—likely influenced by past experiences of trauma—lack mental health services, and are placed in solitary confinement at disproportionately high rates.191 Women and girls need mental health services that are tailored to their unique needs, including the particular mental health needs of pregnant people; take into account histories of mental health issues and trauma; and do not punish them for having a mental illness. Providers must understand that the abuse women face is often directly linked to their gender and provide culturally competent mental health care that particularly addresses the impact of gender-based violence in women’s lives.

Widespread use of solitary confinement

A report from the American Civil Liberties Union on women and solitary confinement notes that solitary confinement is often used to punish women who report sexual harassment or assault in immigration detention facilities.192 This practice further traumatizes women who have already faced abuse in detention and discourages others from coming forward when they are assaulted or harassed. Transgender women are also particularly vulnerable to placement in solitary confinement. ICE often justifies this segregation as “protective custody” after it endangers transgender women by housing them with men—in violation of detention standards. Yet solitary confinement does not provide transgender women with relief from danger; it causes further harm.193 Center for American Progress analysis found that 1 in 8 transgender people in ICE custody were held in solitary protective custody in 2017.194

ICE policy states that placing a person “in segregated housing is a serious step that requires careful consideration of alternatives.”195 Segregation, also known as solitary confinement, is meant to be limited for particularly vulnerable groups, and only used as a last resort. In practice, however, ICE appears to particularly target vulnerable groups for solitary confinement—such as people with disabilities, people with mental health issues, and transgender people—and the use of solitary remains widespread.196

The U.N. special rapporteur on torture has determined that solitary confinement “can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”197 A review of literature on the health impacts of solitary confinement found both physiological and psychological impacts from even short amounts of time in solitary.198 Physical effects included chronic headaches, heart palpitations, trouble with eating and digestion, sensitivity to stimuli, and muscle pains.199 Among the psychological effects were emotional and behavioral impacts such as panic, rage, and poor impulse control, as well as depression, suicidal thoughts, cognitive issues such as memory loss, and psychosis including paranoia and hallucinations.200 These effects last after a person leaves solitary confinement.

Women with mental health issues may be placed in medical isolation or in punitive solitary rather than receiving appropriate treatment. Solitary confinement is particularly dangerous for those with existing mental illness and trauma, which is known to be widespread in immigration detention facilities.201 A study of state jail systems by the Vera Institute of Justice found that the damaging impacts of solitary confinement can be worse for women as a result of increased past experiences of trauma and abuse.202

In May 2019, The Intercept and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) published a review of more than 8,400 reports of solitary confinement in ICE custody from 2012 to 2017.203 More than half of the cases reviewed involved immigrants placed in solitary detention for more than 15 days, the absolute limit recommended by the United Nations. Hundreds of those cases involved people in solitary for months. Reports showed solitary confinement used to segregate LGBTQ immigrants and those with disabilities.204 About one-third of the cases reviewed involved a person with a mental illness, and in more than 500 cases, a person was either placed in solitary confinement on suicide watch or placed on suicide watch as a result of the harm of solitary confinement.205

Policy recommendations

As detention has proved to be deeply harmful to the mental health of women and girls, it should be limited as much as possible, while current systems that provide grossly inadequate mental health care are overhauled. Much like the detention of pregnant people, policymakers should prohibit the detention of people with mental health issues and survivors of trauma unless under extraordinary circumstances. All of the damage that detention does to mental health is significantly worse for people with prior mental health issues. Women and girls are particularly likely to come to the United States with histories of trauma, and locking them up only serves to exacerbate that abuse.

In keeping with international human rights standards,206 the United States must ban all use of solitary confinement, including solitary that is used for punitive, protective, and mental health reasons. Women are particularly vulnerable to the use of segregation and its negative health effects, especially transgender women, women with disabilities, and women who have experienced sexual abuse in detention. Solitary confinement has horrific, lasting impacts on both physical and mental health and should not be permitted under any circumstance.

Finally, policymakers should direct all agencies that detain immigrants to implement culturally competent, trauma-informed standards of medical and mental health care. These standards should include gender-specific guidelines that address the needs of women and girls who are survivors of violence and abuse.207 Oversight bodies must enforce the provision of high-quality mental health services and adequate staffing and training of mental health care providers in detention facilities. For example, OIG reports—as well as recent letters from Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-IA), Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), and Sen. Elizabeth Warren—have expressed concerns about the misuse of solitary confinement in ICE detention.208 Such oversight should continue and be applied to mental health care in all detention facilities.

Sexual abuse is widespread in immigration detention, and transgender women are particularly vulnerable

There is an epidemic of sexual violence and harassment in immigration detention centers, often perpetrated by guards and other detention officials.209 Detained immigrants are particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse, in part due to fear of retaliation that prevents them from reporting abuse, as the same people detaining them may have influence over the outcome of their immigration cases.210

Between January 2010 and September 2017, the OIG received 1,224 complaints of sexual abuse in DHS custody, which includes ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.211 Out of these complaints, only 43 were investigated.212 In 59 percent of complaints, a detention officer or private contractor was identified as the perpetrator.213 These complaints likely only scratch the surface of cases of sexual abuse, as they do not include cases where the survivor did not file a complaint as a result of a language barrier, fear of retaliation, or other reasons.

Despite the presence of Prison Rape Elimination Act standards to prevent, identify, and respond to sexual assault and harassment in detention, facilities with custody of both adults and minors have proved incapable of preventing assault or providing adequate care for survivors of sexual abuse both within and outside detention. Survivors of sexual abuse need both physical and mental health care including HIV services and services for sexually transmitted infections, comprehensive reproductive health care including access to abortion, and trauma-informed mental health services. Detention facilities not only fail to provide quality care for survivors of assault, but they also engage in retaliatory punitive actions toward those who come forward, including placing women who report abuse in solitary confinement.214 In addition, the PREA standards governing the ORR contain a religious exemption that would allow providers to deny care to LGBTQ survivors and deny them comprehensive reproductive health care.215 PREA audits that review how facilities handle allegations of assault did not begin in ICE detention until 2017, 14 years after the law’s enactment, and the few audits that have been conducted have been grossly insufficient.216

LGBTQ immigrants, and particularly transgender women, are especially likely to face sexual abuse and assault in detention. CAP analysis found that in fiscal year 2017, LGBTQ immigrants in ICE custody were 97 times more likely to be victims of sexual abuse and assault than non-LGBTQ people.217 In violation of its own standards, there have been many reports of ICE detaining transgender women in men’s facilities or housing units; of the 17 facilities where ICE detained transgender women in FY 2017, four were all-male facilities.218 Transgender women are much more likely to be assaulted when housed with men, both by men in detention and guards.219 A 2013 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that two-thirds of substantiated incidents of sexual assault of a transgender person in detention were perpetrated by a guard—the same people who are often responsible for separating transgender people from general populations under the claim of their protection.220

To address the crisis of sexual abuse in immigration detention, policymakers must:

- End the detention of immigrants who are particularly vulnerable to abuse, including LGBTQ immigrants and disabled immigrants, except in extraordinary circumstances, and invest in community-based alternatives to detention

- Ensure that transgender women are housed according to their gender identity

- End HHS’ religious exemptions to PREA that allow care to be denied to LGBTQ survivors of sexual abuse and those seeking comprehensive reproductive health services in ORR custody

- Improve oversight and enforcement to prevent sexual assault and harassment in detention and hold perpetrators accountable

Oversight and enforcement

A humane immigration system would seek to limit detention, which has dangerous physical and mental health consequences; use evidence-based standards of care for those who remain detained; and hold officials accountable for providing quality care to people in immigration custody. Instead, the current U.S. immigration detention system regularly inflicts cruelty and neglects the health of people in its custody. Congress and the executive agencies responsible for immigration detention have key roles to play in the oversight and enforcement of health care standards for women and girls in immigration custody. Under the Department of Homeland Security, the Office of Inspector General and the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties have the opportunity to strengthen and enforce quality health care standards and civil rights protections for women in detention.221 Meaningful oversight of women’s health in immigration detention should include confirming that all women receive comprehensive evidence-based standards of care and that there are strong enforcement mechanisms, robust data collection, and broad reform of detention practices.222

Implement evidence-based standards of care

Current standards governing the health of women and girls in immigration custody are varied and unevenly enacted and enforced. To lay the groundwork for high-quality health care provision, policymakers should convene an advisory board of women’s health experts to set evidence-based standards for health care in immigration custody. The board should include diverse representatives including OB-GYNs, primary care physicians, pediatricians, behavioral health experts, community health workers, immigrants’ rights advocates, and reproductive justice advocates.

Many guidelines already exist for providing quality health care to women and girls. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics have extensive, regularly updated guidelines for the care of pregnant people, including prenatal, labor and delivery, postpartum, and miscarriage management.223 In addition, the AAP has issued policy statements on the provision of health care to immigrant children and the detention of immigrant children, including information about key health services for children.224 Incorporating existing medical standards for health care while addressing the specific needs of immigrant women and girls is key to protecting the health of women and girls in immigration custody.

The standards developed by the advisory board should include:

- Primary care and general girls’ and women’s health care, including preventive care, menstrual health, and pain management

- Comprehensive, nondirective reproductive health care and family planning, including contraceptives, abortion, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and maternal health care

- Maternal health care that includes prenatal care, postpartum care, labor and delivery, and miscarriage management

- Trauma-informed mental health care with a specific focus on women’s mental health needs, including the impact of gender-based violence

- Guidelines for care of minors

Enforce standards

Evidence-based health care standards must be adopted across facilities in the departments of Homeland Security and Health and Human Services, and must be binding and apply to all facilities, without the option to waive compliance. Congress and the agencies responsible for the custody of women and girls, including DHS and HHS, must work together to enact strong enforcement measures and ensure the provision of quality health care in immigration custody.

Congress should explore a range of options for enforcing health care standards in detention facilities. Among the possible options are financial penalties and incentives, including fines and binding payment on contracts to compliance with standards, as well as the loss of contracts and facility closure for those who fail to comply with standards and have a record of rights abuses. Regular inspections of every facility with custody of immigrant adults and children, and reports on those inspections to Congress, are also important accountability measures.