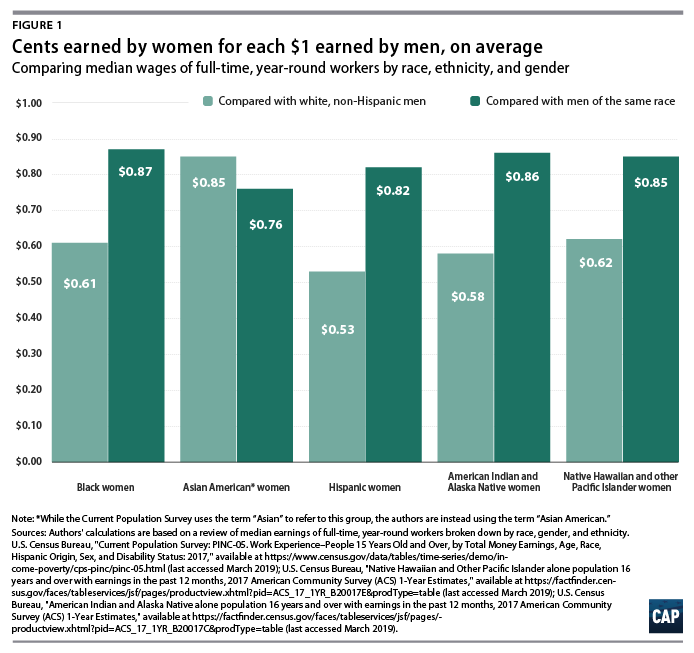

The concept of equal pay for equal work is a cornerstone workplace principle firmly rooted in American core values of equality and fairness. The vast majority of Americans support equal pay—regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level—and it is frequently identified as a top priority, especially for those who face sharp pay disparities, such as women, workers of color, workers with disabilities, and LGBTQ workers.1 Not surprisingly, many policymakers are quick to voice a pro-equal pay mantra to prove their commitment to upholding equal pay laws. Yet despite the professed support for this issue, persistent pay disparities make clear that equal pay for equal work is far from a reality. In particular, women working full-time, year-round earn, on average, only 80 cents for every dollar earned by men.2 This gap is significantly worse for women of color, and the problem persists when comparing the earnings of women and men of the same race or ethnicity.3 (see Figure 1)

These wage gaps only grow over time. Research suggests that women lose more than $400,000 over a 40-year career due to the wage gap. For black women and Latinas, these lifetime earning losses can equal $946,120 and $1,135,440, respectively.4

Separating myth from reality

Securing equal pay requires more than words and lofty platitudes. It requires bold action at all levels. Unfortunately, the issue has become a partisan football, leading to misinformation that has stifled progress in areas where executive or legislative action could be particularly effective.

Important progress made during the Obama administration has come under systematic attack by the Trump administration, stalling Obama-era rules to promote greater pay transparency, collect pay data, and strengthen federal equal pay enforcement.5 Moreover, partisan disagreements spurred by opponents of equal pay reform have thwarted two leading federal proposals, the Paycheck Fairness Act and the Fair Pay Act—both of which would advance much-needed improvements to increase pay transparency and strengthen federal enforcement tools used to ensure compliance with the law.6 The Paycheck Fairness Act was reintroduced in January 2019 by Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) with the support of the entire Democratic House Caucus.7 The bill’s provisions would help protect workers from retaliation for discussing pay, limit the use of salary history in making hiring decisions, close legal loopholes that have helped employers avoid liability, implement negotiation skills training, require regular disaggregated pay data collection to strengthen enforcement, and improve the remedies available to plaintiffs who file sex-based wage discrimination claims under the Equal Pay Act.8 The Fair Pay Act has yet to be reintroduced in the 116th Congress. In contrast, opponents of comprehensive reform have pushed weaker measures. For example, in 2017, Sen. Deb Fischer (R-NE) introduced the Workplace Advancement Act, which proposed a narrow anti-retaliation protection for workers who discuss their pay at work.9 However, its language outlining the relevant standard that would be used to trigger the protection is unclear, and the proposal as a whole falls far short of comprehensive reform.

To make progress on equal pay and combat pay discrimination, it is critical to separate rhetorical myths from real solutions that can make a concrete difference for working families. Policymakers must understand the facts about the discriminatory practices that continue to affect women’s earnings, as well as the various factors behind the persistent gender wage gap, in order to effectively promote, enforce, and protect equal pay for all. Most importantly, policymakers must reject false narratives used as a subterfuge to stall or undermine potential equal pay reforms that are long overdue. Here are 10 myths about equal pay as well as the realities behind them, which bolster the case for substantive reform.

Myth 1: Pay discrimination is a not a significant problem

Reality: One frequent complaint made by critics who question the need for stronger equal pay protections is that pay discrimination is not a serious problem. These critics are skeptical of the 20 percent wage gap between men and women, as they do not see it as an accurate measure of inequality and argue that much of this gap can be explained by differences in education, skill, or work choices. However, researchers who study the gender wage gap have found that it can only partially be explained by measurable factors such as educational or seniority differences. There is also a portion of the gap that is unexplained by these traditional measures, and researchers often identify discrimination as the likely explanation because it tends to be harder to quantify through precise measurements.10 (see Table 1) Therefore, discrimination—while not the only factor driving the gender wage gap—is an important piece of the puzzle that needs to be addressed.

Moreover, when it comes to workers’ pay, most employers have a legal—and moral—imperative not to discriminate based on gender. This obligation does not disappear simply because discrimination may not be the only factor causing a pay disparity. Discrimination, no matter the scope, has no place in the workplace and should never be excused or dismissed as irrelevant or inconsequential. Given that women consistently identify unequal pay as a workplace problem,11 taking steps to improve their ability to challenge discriminatory practices should be a top priority.

Myth 2: Women’s occupational choices can explain the gender wage gap

Reality: Those who simply tell women to get better jobs in order to secure equal pay are ignoring much of what is known about pay disparities in the workplace. In the vast majority of occupations, women earn less. Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2018 show that, of at least 125 occupations with comparable data, men earned more than women in all but 12 occupations.12 Even in so-called pink-collar jobs in which women are overrepresented, they still earn less than men.13 Accordingly, a woman can move from one occupation to another to seek higher pay, but a job change does not ensure that she will not face a pay disparity. Women deserve to be paid fairly, wherever they work.

Furthermore, dismissing the gender wage gap as merely a reflection of women’s choices ignores the gap’s underlying causes. Discriminatory attitudes can lead to women being pushed out of fields with higher wages or lead to them being underpaid in both high- and low-wage jobs. Recent studies have found that women in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) occupations—which tend to pay more—have higher attrition rates than men in these fields and than women in other occupations.14 Explicit and implicit gender biases likely factor into their decisions to depart. A 2008 study found that 52 percent of women in STEM quit their jobs by midcareer, citing feelings of isolation, unsupportive work environments, unclear rules about advancement and success, and extreme work schedules as the key reasons for leaving.

The lack of strong work-family policies also contributes to pay disparities because women are frequently expected to handle much of their family’s caregiving needs and therefore end up spending more time than men out of the office to shoulder those responsibilities. Mothers, for example, are often pushed out of the workforce because of the absence of comprehensive paid leave policies and affordable caregiving options.15 Research shows that providing paid family and medical leave policies allows mothers to return to work more quickly after childbirth, work longer hours if desired, and be more productive—all of which can help narrow the wage gap.16 Rather than dismiss the wage gap as a product of women’s choices, policymakers should pursue comprehensive solutions, such as paid family and medical leave, earned sick days, affordable child care, and fair scheduling, that can address the gap’s underlying causes.17

Myth 3: Changes to the law and more government enforcement are unnecessary because private employers proactively evaluate and modify their pay practices

Reality: Voluntary actions by private employers should be commended, but they are not a substitute for strong legal protections backed by government enforcement to hold institutions accountable. To make the promise of equal pay for equal work real, it must be more than a voluntary option. The power of the law must be available to challenge pay discrimination in order to ensure that women and men are paid fairly for their work and can vindicate their rights. Strong legal protections uphold America’s commitment to equality and hold employers, of all sizes, in all regions, and in all industries, accountable for equal pay.

Myth 4: Data collection efforts are unnecessary and onerous for businesses and will lead to sensitive personal information being made public

Reality: To figure out whether a worker is being paid unfairly, it is essential to have access to pay data. It is virtually impossible to determine if discrimination is taking place without the actual data showing how much workers are being paid. Therefore, collecting pay data is crucial to ensure compliance with the law and to accurately evaluate pay practices and trends.18 Employer complaints that routine pay data collection is overly difficult and burdensome are wholly unpersuasive and insult the technological capabilities of America’s workforce. Employers regularly maintain pay data, and many are already obligated to submit such data if asked by enforcement officials during an investigation. Furthermore, federal enforcement officials have maintained the confidentiality of employer data for decades; there is nothing to suggest that they will not continue to do so when employers submit their pay data.19 Robust enforcement should include regular, full access to disaggregated pay data so that enforcement officials can evaluate employer pay practices, identify trends, and fully investigate pay discrimination claims.

Myth 5: The salary history of a potential employee is necessary and unbiased information that employers need to make decisions about compensation

Reality: The use of salary history when determining compensation or deciding whether to hire a worker potentially allows employers to carry forward discrimination throughout women’s careers. All women experience pay disparities. Using a woman’s prior salary—which could be negatively influenced by discrimination—to determine her future salary risks perpetuating past discriminatory pay practices and keeping her at an economic disadvantage. While defenders of using salary history argue that the free market accurately dictates an individual’s worth, this view ignores the troubling reality that the same free market consistently undervalues women and is not immune to the biases and stereotypes that can influence worker compensation. Limiting the use of salary history in employment decision-making can help to stop the perpetuation of discriminatory pay practices that otherwise follow women from job to job.

Myth 6: Increasing civil damages will encourage the filing of frivolous lawsuits that enrich high-powered trial lawyers

Reality: Pursuing any employment discrimination claim—including a pay discrimination claim—takes time and substantial resources. Many claimants do not have the resources to hire expensive lawyers and cases can take years to resolve, making quick monetary windfalls highly unlikely. Moreover, the pressures associated with litigation can take a severe toll on a claimant’s work and home life. Even when a claimant succeeds, the law places limits on the type and size of the monetary damages that can be awarded under the Equal Pay Act20 and Title VII.21 Concerns about the unjust enrichment of plaintiffs’ lawyers are a distraction and blur the fact that employment discrimination cases are harder to win and these plaintiffs tend to be less successful than other civil claimants.22 Thus, filing an employment discrimination case is far from the surefire, get-rich-quick strategy that opponents of equal pay reform often suggest. Ultimately, workers who have experienced pay discrimination should have access to full range of remedies that reflect their losses. Damages, therefore, must be significant enough to both cover the full range of costs involved in bringing a lawsuit and effectively deter discriminatory behavior in the future.

Myth 7: It will be impossible for employers—even those operating in good faith—to defend themselves against claims of pay discrimination using the “factor other than sex” defense because the defense is being eroded

Reality: The Equal Pay Act includes specific defenses that employers can invoke to justify a pay difference between a male and female employee. One of these affirmative defenses is called the “factor other than sex” defense, which enables an employer to defend a pay differential by showing that the decision was based on a legitimate factor—such as experience, education, or training—and not gender.23 Unfortunately, the “factor other than sex” language has been interpreted so broadly by courts that it has provided a legal loophole for some employers to successfully defend a pay decision that sounds neutral on the surface but is rooted in gender bias. To help ensure that legitimate, unbiased factors are being used to make pay decisions, policymakers should work to modify the existing language of the Equal Pay Act, making clear that the reasons for gender-based pay differences must be based on business necessity and clearly related to the job in question.

Myth 8: Women earn less because they ask for less

Reality: While research varies on how much women negotiate their pay compared with men, the consistent finding is that women who do negotiate are penalized much more harshly.24 A 2007 benchmark study of negotiating strategies found that people overwhelmingly perceived women as less “nice” and more “demanding” than men, indicating implicit bias.25 The same study found that people were less inclined to hire or want to work with women who negotiate. In 2018, a separate study found that when rejected for a pay raise, women were 8 percent more likely than men to be told that there was a budgetary constraint underlying the decision.26 The same study also found that women of color were 19 percent less likely than white men to secure a raise when negotiating.27 So, while stronger negotiation skills could potentially help some women raise their wages, it is unlikely that better skills alone would ensure equal pay or close the wage gap. To help remedy this issue, the Paycheck Fairness Act proposes a grant program for the development of negotiations skills trainings, which represent one component of a comprehensive set of reforms to strengthen equal pay protections and combat discrimination.

Myth 9: The inability of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act to close the gender wage gap proves that new legislation is not the answer

Reality: The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act focused on correcting an interpretation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in pay discrimination cases. It was a response to the 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., where a divided court ignored decades of case law to rule that, under Title VII, workers must file pay discrimination claims within 180 days of the original act of discrimination.28 Given that pay discrimination is notoriously difficult to detect and that few workers know when a discriminatory decision is made, the ruling—if left standing—would have made it nearly impossible for plaintiffs to file pay discrimination claims in a timely manner. In 2009, then-President Barack Obama signed the Ledbetter Act, rejecting the Supreme Court’s interpretation and restoring the prior rule. Under the new law, workers have 180 days from the last discriminatory paycheck—rather than the original decision—to file their claims.29 While immensely important in returning to the status quo, the Ledbetter Act did not go beyond current law; neither did it address the ongoing need for stronger equal pay protections under the Equal Pay Act or implement comprehensive strategies to address the factors that fuel the wage gap. The next step is to build on the Ledbetter Act to enact concrete, affirmative reforms that can help strengthen equal pay protections for workers.

Myth 10: An anti-retaliation provision that prohibits employers from penalizing workers who discuss their pay is sufficient to address existing pay disparities and gaps in equal pay protections

Reality: One challenge that many workers face when trying to unearth pay discrimination is that they do not know how much their coworkers are being paid. This problem is exacerbated in situations where employers discourage employees from discussing their pay at work or have rules that prohibit employees from engaging in such discussions altogether. Therefore, it is important to prohibit pay secrecy and retaliation against workers who discuss their pay.30 Yet an anti-retaliation protection—standing alone—does not address the multiple factors that fuel pay discrimination; nor does it address the overall need for stronger enforcement tools and equal pay protections. Combating pay discrimination effectively requires improved access to pay data so that enforcement officials can scrutinize employer practices. Moreover, policymakers should work to close loopholes in the law so that workers can successfully challenge equal pay violations and should make targeted efforts to address stereotypes and biases about women that result in them being valued less than their male colleagues or excluded from higher-paying jobs. These strategies, coupled with strong work-family policies that help women and men deal with the dual demands of work and family, are critical to helping improve pay practices and ensuring equal pay.

Conclusion

Policymakers must do more than mouth equal pay rhetoric; they must back up their words with concrete action to strengthen equal pay protections and combat discriminatory pay practices. Such efforts should include promoting pay transparency, protecting workers from retaliation, disclosing disaggregated pay data to enforcement officials, prohibiting the use of salary history, and stepping up enforcement efforts where needed.

In addition, it is also essential that policymakers commit to family-friendly workplace protections, such as paid family and medical leave, access to sick days and flexible scheduling, affordable childcare, and other benefits that are essential to ensuring that working families can not only survive but thrive.

Women deserve to be paid fairly for their work. It is imperative that policymakers take immediate actions to strengthen equal pay protections—protections that are long overdue.

Jocelyn Frye is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Robin Bleiweis is a research assistant of women’s economic security for the Women’s Initiative at the Center.