Download this brief (pdf)

Two recent stories in The New York Times highlight the problems single women can encounter with health insurance, and sometimes with tragic consequences. Nikki White suffered from lupus and lost her job—and also her employer-based health insurance coverage—when she became too sick to work. She could not obtain individual coverage because of her pre-existing condition of lupus and, as an unmarried woman, had no one who could cover her on their insurance plan. At the age of 32, she died from lack of treatment of a usually manageable chronic disease.

Melissa Whitaker, age 31, has had two kidney transplants, fortunately paid for by an obscure Medicare provision that covers her particular illness even for people under age 65. However, Medicare only covers three years of the expensive medicine she will need for a lifetime, and she must soon find a way to get private health insurance to help pay the exorbitant costs.

That may prove difficult. Melissa has already lost insurance a couple of times: First when she got divorced and later when she lost her job because of additional health concerns that prevented her from continuing work. She and her boyfriend are now considering getting married so that she can be added to his employer-sponsored plan.

Recent media coverage of health care reform has focused on the bias women face in the current system and what they stand to gain from the pending overhaul. Little attention, however, has been paid to the additional problems unmarried women face in obtaining and maintaining health insurance.

Unmarried women cannot rely on receiving coverage through a husband’s plan. And because they usually have only their own income, they may not be able to afford the premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket costs required by a plan that is willing to cover them. Furthermore, married women who have health insurance through their husbands are vulnerable to losing their coverage if the marriage ends.

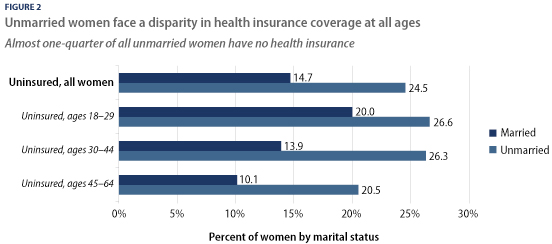

In fact, 25 percent of unmarried women ages 18 to 64 are uninsured, compared with only 15 percent of married women in the same age range. While 45 percent of women this age are unmarried, they represent 60 percent of all uninsured nonelderly women.

The current Great Recession—as it’s called—is adding to these numbers. Because the U.S. system ties access to health insurance so closely to employment, high and rising unemployment can be doubly devastating. There are currently 15.1 million unemployed workers, 6 million of them women, many of whom have lost not only their job but their health insurance as well.

This brief will outline why unmarried women are particularly vulnerable in our current health insurance system and how health reform legislation pending before Congress can help more of them receive and pay for coverage.

The health insurance system discriminates against women

Forty-six million Americans do not have health insurance because of large gaps in the patchwork health insurance system that includes employer-sponsored plans, government-provided coverage, and the individual market. However, women as a whole face unique problems in the health insurance system.

For instance, in a practice known as “gender rating,” insurance companies in the individual market routinely charge women higher premiums than men—in some cases up to 48 percent more—for the same plan. Women also have higher out-of-pocket costs and greater rates of being “underinsured” because they are more likely to suffer from a chronic condition and have more routine health care needs.

In addition, many individual market insurance plans do not even cover basic services such as maternity care and will deny coverage in whole or in part because of what they deem to be pre-existing conditions, such as domestic violence or having had a Caesarian section.

As a result, women are more likely to delay or go without needed medical care because they cannot afford it. And a recent study found that over half of all medical bankruptcies are filed by women, most of whom had some type of health insurance coverage when they filed.

Unmarried women face additional barriers to obtaining and maintaining health insurance

Women’s challenges with health insurance are even worse if they are unmarried. These women typically face the added burdens of relying on only themselves for insurance coverage and having fewer resources to purchase insurance.

Married women are much more likely than single women to have employer-sponsored insurance, in large part because they often can get insurance through their husband’s job. Three-quarters of married women have employment-based insurance, but only half of these women have their own insurance benefits, while the other half are covered as dependents (see Figure 1 below).

Unmarried women cannot turn to a husband’s plan, as many married women can, which puts them in a particularly tough spot if they become too sick to work or lose their job. As a result, only half of unmarried women have employer-sponsored insurance. And when unmarried women do have employer coverage, they are more likely than married women to have it through their own job—only 10 percent are covered as a dependent.

Many single women (nearly 90 percent) who receive dependent coverage are still young enough (ages 18 to 24) to be covered by a parent’s plan. And some unmarried women may be in a recognized same- or opposite-sex domestic partnership that qualifies them to receive dependent coverage. However, such benefits are still relatively uncommon, and most unmarried women do not have a domestic partner.

The numbers of unmarried, uninsured women are only likely to rise in the midst of the Great Recession, which has hit single mothers hard—over the last year, unemployment among this group has increased by 40 percent according to a congressional Joint Economic Committee report from Congress—and has ramifications for their families. The same study showed that approximately 276,000 children of unmarried women have lost their health insurance as a result of the labor market contraction.

Women on their own are thus typically under more pressure than married women to find a job with health insurance and they have less flexibility to reject a job that comes with insurance benefits. In contrast, married women who can be covered by their husband’s plan may be more willing to take jobs that don’t offer insurance or undertake entrepreneurial pursuits. In fact, data show that married women are more likely to have a job that does not offer insurance.

Affordability is another critical issue for single women. Unmarried women tend to be poorer (22 percent of nonelderly unmarried women are poor, compared with 6 percent of married women), and have much lower household incomes than married women—tens of thousands of dollars less in fact. The half of unmarried women who do not receive their health insurance through a job must seek insurance from the government—if they qualify—or in the private individual market, where it is much more expensive due to a lack of regulation and consumer bargaining power. Cost is likely a big reason why only 7 percent of unmarried women purchase private health insurance (Figure 1) and why so many unmarried women remain uninsured (Figure 2).

For women with the lowest incomes, government-sponsored Medicaid is sometimes a refuge, especially for women with children. Indeed, among poor women, unmarried women are more likely to have health insurance than married women—62 percent versus 58 percent—because they are slightly more likely to qualify for assistance. But poverty alone is not always sufficient to qualify a woman for Medicaid: 38.5 percent of poor unmarried women remain uninsured.

Because of these gaps in the U.S. health insurance system, almost one-quarter of all unmarried women do not have any health insurance at all. And the majority of uninsured women (60 percent) are single. This disparity exists in every age group, as Figure 2 below shows.

Indeed, the notion of “young invincibles” who can risk going without insurance is simply a myth. Young women have important reproductive health needs, such as cancer screenings, birth control, and annual well-woman care. Yet young women (ages 18 to 29) represent nearly half (45 percent) of all unmarried uninsured women and more than one-quarter of all uninsured women.

Married women who become single risk losing their insurance

Married women are not immune from the problems unmarried women face in our health care system. Dependence on a husband leaves many married women vulnerable to losing their health insurance should they become divorced, separated, or widowed. In 2008, almost 40 percent of married women received employer-sponsored insurance as a dependent (Figure 1), most of them through their spouse. One study found that divorcing or separating women were three times more likely to lose their health insurance than were women who remained married during a two-year survey period.

Women nearing retirement are also at risk of becoming and staying uninsured. The median age of widowhood is 58 years, but Medicare coverage does not begin until age 65. Thus, many widows who had been covered by their husband’s employer-based plan must wait several years for Medicare coverage. And because of age and health status discrimination, older women may have more difficulty finding a job with benefits or may face denial of private coverage or higher premiums.

The fear of losing insurance is so severe that some former couples have resorted to insurance fraud by not reporting a divorce in order to maintain spousal coverage. Other women choose to stay in a bad marriage simply for the sake of the health insurance. This is a particularly dangerous situation for women who are trapped in an abusive relationship—they may want to leave, but they cannot afford to go without health insurance, especially given that some insurance companies deny coverage under the guise that domestic violence is a preexisting condition.

Existing policies

A few policies help unmarried people obtain or maintain health insurance, including a law called the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Though most think of COBRA’s continuing health coverage provisions as a tool to help employees keep their health insurance after they lose their job, it is also available for people at risk of losing their health coverage due to a change in their marital status.

However, COBRA only applies to employers with at least 20 employees and only if the employer offered insurance in the first place. In addition, COBRA premiums are usually prohibitively expensive. To address the cost problem, the recent American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided laid-off workers and their families with subsidies in the form of a tax credit equivalent to 65 percent of the COBRA premium for up to nine months.

Another policy that has helped some single women keep their health insurance extends coverage under a parent’s health plan. In the past few years, some states have passed laws that require insurers to cover young adults through their parents’ health insurance beyond their school years. The laws usually require that the young adult not be married or a parent, and the age cut off varies by state from 21 to 31.

Anticipated policy changes that can help

The above policies are a start, but they do not go nearly far enough to address the health insurance needs of unmarried women. Only one-half of unmarried women have employer-sponsored health insurance; the other half must find insurance elsewhere. However, insurance in the individual market is often not an affordable or available option for unmarried women. These women have high rates of poverty and low household incomes and, like married women, are often excluded from private coverage for discriminatory reasons, while Medicaid’s tattered safety net simply fails to reach millions of poor and low-income women.

Several policies that would especially help unmarried women are included in health care reform legislation now pending in Congress.

Better coverage

The following policies in pending health reform legislation would help unmarried women by making it easier to purchase quality health insurance in the individual market and expanding the safety net to cover more low-income Americans. And they would require insurance plans to offer coverage to more applicants.

- The ability to purchase affordable, quality health insurance though a health insurance “exchange.” This proposal would create a marketplace where individuals who aren’t covered by an employer’s health plan could comparison shop and purchase coverage with benefits and rates similar to those negotiated by large employers.

- Expansion of Medicaid. The Medicaid program would be expanded to help lower-income individuals obtain health coverage. It would increase eligibility to anyone with an income up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line, regardless of whether they have children.

- Allowing young adults to stay on their parents’ plan longer. Both the House and Senate bills contain a provision that would require insurance companies to provide dependent health insurance coverage for children up to age 26 (in the Senate) or 27 (in the House).

- Better regulation of the health insurance market. These provisions would guarantee that everyone would be offered insurance regardless of their health status. All the bills being considered would make it illegal to deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions and would not allow insurance companies to charge higher premiums for women than men.

More affordable

Buying a health insurance plan on one’s own is currently very expensive and even with insurance, health care costs can add up to unaffordable levels. The following policies will help more Americans, especially single women, afford health insurance and will lower their out-of-pocket costs.

- Premium subsidies. The legislative proposals would provide subsidies on a sliding scale to enable more people to purchase health insurance within the health insurance exchange.

- Caps on out-of-pocket spending. Limits would be placed on the amount someone spends on health care—for example, co-pays, and deductibles—in a single year or over a lifetime, which would greatly reduce the incidence of medical bankruptcy.

Conclusion

In the current health insurance system, unmarried women are uniquely challenged in obtaining and maintaining health insurance. They rarely have the option to get insurance through another person and generally have less income to pay insurance and health care costs. What’s more, married women are vulnerable to changes in marital status that could affect their coverage.

The stories of Melissa Whitaker and Nikki White illustrate why our national health insurance system must be reformed. Through sensible policy changes that expand affordable, quality coverage to all Americans, millions of women on their own will no longer be excluded from our health insurance system.

Liz Weiss is a Policy Analyst at the Center for American Progress focusing on the economic security of unmarried women. Ellen-Marie Whelan is a Senior Health Policy Analyst and Associate Director of Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. Jessica Arons is Director of the Women’s Heath and Rights Program at the Center for American Progress. The authors wish to thank Heather Boushey for her assistance with this report.

Download this brief (pdf)