All workers will at some point need time away from work to care for themselves, a sick child, or an ailing loved one. Having access to paid sick days means that workers do not have to sacrifice a paycheck to maintain their own health or the health of their family. Unlike most other highly developed countries, the United States has no federal law that guarantees workers access to paid sick days—a reality that means millions of workers have no support if they or a family member fall ill.

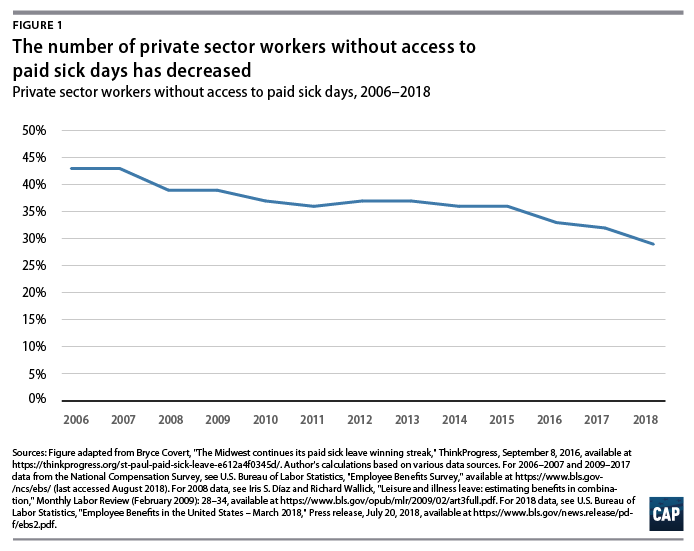

In 2018, 34.2 million, or 29 percent of, private-sector workers did not have access to paid sick days. The disparity in access is worse for some types of private-sector workers: 61 percent of part-time workers, 69 percent of workers in the lowest-wage jobs, and 48 percent of service workers do not have access to paid sick days. While the overall number of private-sector workers without access has decreased from previous years due to the growing number of state and local paid sick days laws, far too many workers are left without the economic security or health benefits that paid sick days provide.

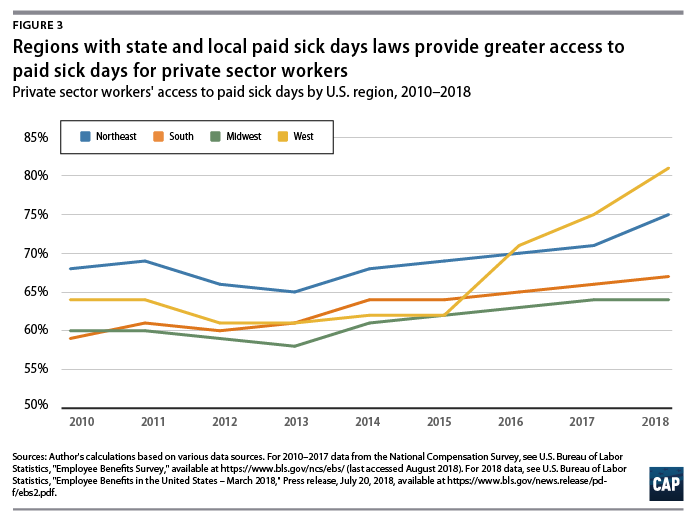

Access to paid sick days is especially uneven by U.S. region. While the unevenness illustrates the success of state and local laws in establishing this important workplace protection for private-sector employees and their families, there are still too many workers—particularly in the Midwest and South—without access to paid sick days. In 2018, for example, more than 1 in 3 private-sector workers in the Midwest did not have access to paid sick days, compared with about 1 in 5 of their counterparts in the West. Workers’ ability to maintain their income in the face of their own or a family member’s illness should not be dependent on where they live and work.

This column first looks at how paid sick days benefit workers, families, and employers in the private sector. It then details the disparities in access to the protection and discusses what is needed to provide a comprehensive federal solution.

Paid sick days laws are good for workers, families, and employers

While paid sick days laws can vary between states and localities on the length of protection and amount of wage replacement, having a basic protection is nonetheless critical for workers and their families, as well as valuable to employers. The guarantee of paid sick days is crucial for workers and ensures that they can recover from short-term illnesses without losing their paychecks. Importantly, some laws even cover workers’ chosen families, allowing them to care for individuals with whom they have formed a close, family-like relationship, such as long-term partners, friends who are as close as siblings, and neighbors. All families need paid sick days, and laws that are inclusive of chosen family can be especially beneficial for LGBTQ people and people with disabilities.

Workers with access to paid sick days tend to have less severe and shortened periods of illness, reducing the amount of time they are too sick to work. And when workers stay home to recover instead of going to work when they are potentially contagious, they lessen the odds of spreading their illness to coworkers and the public. Paid sick days also help reduce presenteeism, when workers are at work but are less productive due to sickness, and worker turnover, both of which can provide significant cost savings to employers.

Some critics of paid sick days legislation have claimed that passing these laws will lead to negative economic effects and create cost burdens for employers. However, in states and localities with laws that require qualifying employers to provide workers with paid sick days, the laws have not been shown to lead to increased unemployment. Most businesses in states and localities with paid sick days laws have reported that the policies have no negative effects on cost impacts and require no changes to hiring and hours practices. Research on paid sick days laws shows that they do not harm employers or the economy—but do provide significant benefits to workers and their families by helping them maintain their economic security and health.

Workers’ access to paid sick days has increased yet remains uneven

New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show a continued gap among different categories of workers in access to paid sick days. Although more than half of service workers now have access to paid sick days, this is significantly lower than the 90 percent of private-sector managers and professional workers with access. Full-time workers are twice as likely to have access to paid sick days as part-time workers. And the disparities are worse when access is compared across wage earners. Ninety-two percent of private-sector workers in the highest-wage decile have access to paid sick days, while only 31 percent of workers in the lowest-wage decile have access. This gap continues to narrow as additional states and localities enact paid sick days laws, but it is still too wide for the low-income workers who can least afford to lose out on pay or a job to deal with their own or a family member’s illness.

Access is even lower for many workers of color, especially Hispanic and American Indian or Alaskan Native workers and women. In 2014, Hispanic workers were 27 percent less likely than white workers to have access to paid sick days. American Indian or Alaskan Native workers were 16 percent less likely than white workers to have access. Also in 2014, Hispanic women—at 49 percent—were the least likely among women to have access to paid sick days. Lack of access can disproportionately affect women, as they are more likely than men to provide care to sick loved ones. Overall, Hispanic and American Indian or Alaskan Native workers and women face greater vulnerability to negative health outcomes or financial strain because of their lack of access to paid sick days.

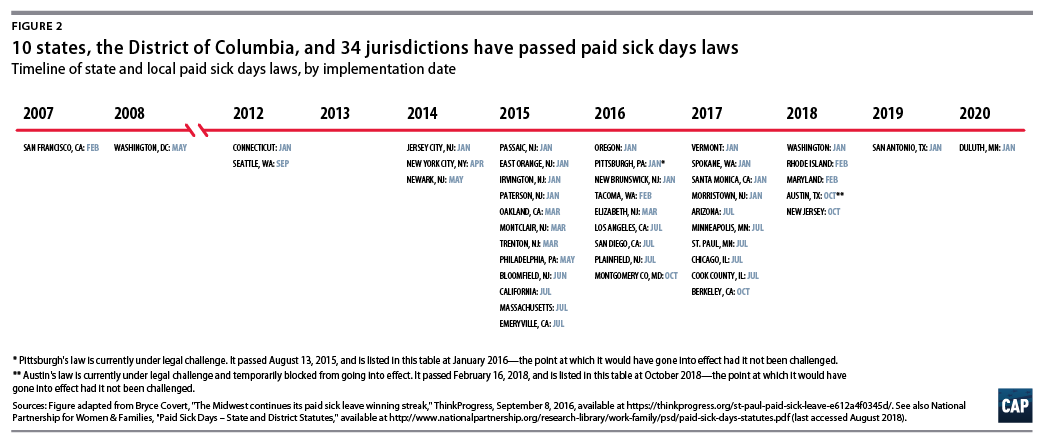

Furthermore, over time, the passage of state and local laws has expanded access to paid sick days. Currently, 10 states, the District of Columbia, and 34 jurisdictions have passed paid sick days laws, providing access to more and more workers.

Most of these paid sick days laws, especially the statewide laws, are concentrated in the West and Northeast regions. Private-sector workers in these regions—particularly low-income and part-time workers—formerly without access to paid sick days through their employer gained protections under these laws. Simply due to where they live and work, workers in these regions have greater access to paid sick days. Since 2015, when most of the statewide laws started going into effect, gaps in access to paid sick days among regions have grown wider. (see Figure 3) In 2018, for example, 36 percent of private-sector workers in the Midwest and 33 percent of private-sector workers in the South did not have access to paid sick days, compared with only 19 percent and 25 percent of these workers in the West and Northeast, respectively. Although paid sick days laws have proven effective at expanding access, the patchwork of laws across the country leaves too many workers behind.

Federal legislation should expand access to paid sick days

The Workflex in the 21st Century Act currently in the House of Representatives threatens state and local paid sick days laws and could lead to a reduction in workers’ access to these critical workplace standards. The bill creates a loophole that allows businesses to circumvent state and local laws that expand access to paid sick days and fair scheduling by opting into a federally qualified flexible workplace arrangement plan with minimal requirements. If the bill passes, employers could offer a minimum number of compensatory days based on the employer’s size and the employee’s tenure—toward which they could choose to count up to six federal and state holidays. Employers with a qualified plan would have the discretion to deny workers’ requests for leave if the employer asserts that it would unduly disrupt their business. For example, a coffee shop owner with a qualified plan could potentially deny an employee’s request for leave to care for a sick child if the request falls during the morning rush. The Workflex bill would undermine the success of state and local paid sick days laws and could actually make matters worse for the 71 percent of private-sector workers who currently have access to paid sick days.

To truly improve the existing patchwork of state and local laws, policymakers should reject harmful proposals such as the Workflex bill and prioritize a comprehensive national paid sick days law such as the Healthy Families Act. This bill would set a national standard for private-sector workers at businesses with at least 15 employees to earn up to seven paid sick days a year and would help close the access gap across all incomes, occupations, and regions. By passing the Healthy Families Act, Congress would enable workers to care for themselves and their families without sacrificing a paycheck, as well as ensure positive outcomes for employers and the U.S. economy.

Diana Boesch is a research assistant of women’s economic security for the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress.