See also:

This column contains a correction.

Women working full-time, year-round, earn an average of 78 cents for every dollar earned by men working full-time, year-round. Equal Pay Day commemorates this: It would take women from January 1, 2014, until April 14, 2015, to earn what men earned from January 1 to December 31, 2014. While eminently useful, this top-line number hides nuances about the causes of the gender wage gap. Differences in occupation and industry—specifically, the types of jobs that men and women hold—help explain nearly half of the gender wage gap, while a look at occupational data from 2014 can help explain the top-line number.

First, it is important to note that there are causes of the gender wage gap beyond the differences in the types of jobs men and women tend to have. Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn completed their famous analysis of the causes of the gender wage gap in 2007 and were able to attribute nearly 60 percent of it to measurable factors, such as the facts that women tend to have shorter job tenures than men and that women tend to work in lower-paying jobs and industries. Still, around 40 percent of the gender wage gap remains unexplained and is likely due, at least in part, to conscious or subconscious discrimination.

There are those who are quick to suggest that the gender wage gap could be closed if women were to make different “choices” about their work and careers. Overall, for example, women are more likely to work fewer hours than men, often due to caregiving responsibilities: In 2013, in households with children younger than 6 years old, employed women spent 38.4 more minutes per day caring for children than employed men; they also spent 41.4 more minutes doing household activities, such as cleaning and cooking. Women are also more likely to leave the labor force to take care of children or other relatives, which affects their workforce experience; differences in experience explain 10.5 percent of the wage gap. While this is often a choice, it is influenced by family needs and by societal understandings of women’s responsibilities when it comes to housework and child care.

Moreover, women are also far more likely to work in service or caregiving occupations, and these jobs tend to pay less. Cultural socialization about what is considered to be “men’s and women’s work,” as well as the worth of that work—rather than innate female qualities—lead women to these jobs and away from higher-paying jobs in less traditional fields.

How do these occupational and industry differences shake out? Working women are concentrated in education and health services; this industry category alone accounts for 35.7 percent of female workers. In comparison, the most common industry for men is wholesale and retail trade, which accounts for just 14.3 percent of male workers. In other words, because of this concentration, the top five industries for women account for two-thirds of female workers, while the top five industries for men account for only half of male workers. As these numbers show, women remain highly clustered in industries related to care and service work, which are often associated with traditional understandings of “women’s work.” As occupational data show, this work includes jobs that pay less overall.

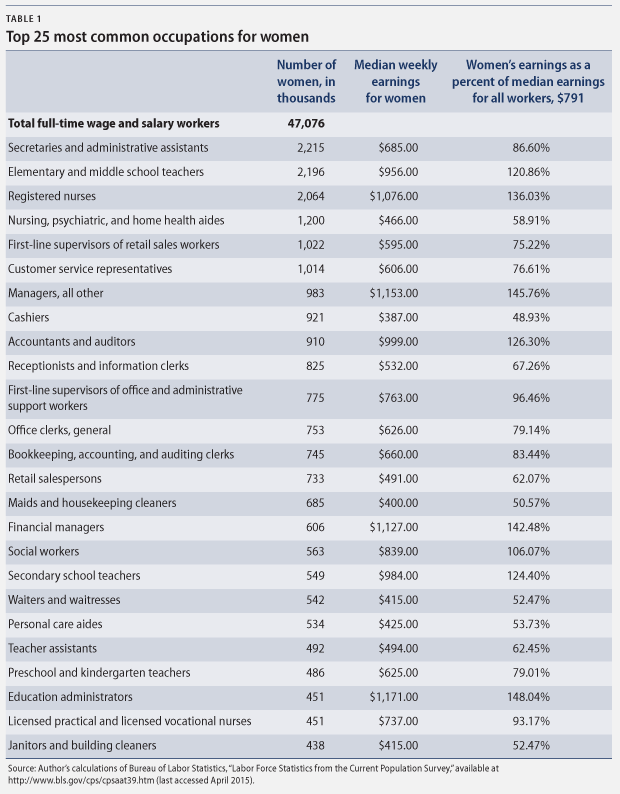

Looking at specific occupations illuminates these data in a different way: Women may be concentrated in the health and education fields, but are they high-earning surgeons or low-earning health care aides? Are they higher-earning university administrators or lower-earning preschool teachers? The table below shows that they are often on the lower end of the spectrum. The most common jobs held by women in 2014—accounting for 47.1 percent of all working women—are listed in Table 1.

Many of these jobs’ compensation falls far below the median weekly earnings—$719 per week—for women workers overall, as well as the median weekly earnings for all workers, $791 per week; a gap between men’s and women’s wages exists in every occupation listed.

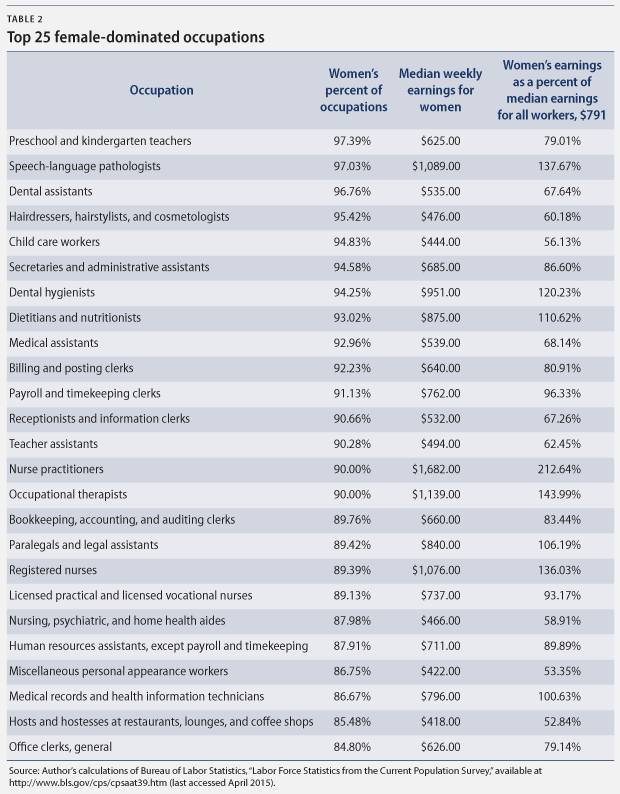

This gap persists even in occupations that employ more women than men. The occupations most dominated by women in 2014 are listed in Table 2.

Meanwhile, the occupations most dominated by men were in the construction and related trades, including brickmasonry, roofing, and plumbing. Furthermore, only 8 of the top 25 female-dominated occupations paid more than the median wage for all workers, compared with 15 of the top 25 male-dominated jobs. Likewise, six of the most-female-dominated jobs had median weekly earnings that were less than two-thirds of the overall weekly median earnings for all workers. None of the most common male jobs had median weekly earnings below 70 percent of the overall weekly median wage.

Gendered occupational segregation is an enduring issue. A recent study from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research found that although the level of occupational segregation has decreased over the past few decades, it has barely changed since the 2000s.

This analysis highlights that much can be done to improve women’s current work situations and to help shrink the gender wage gap, in additional to encouraging women to train for, enter, and stay in higher-paying jobs and nontraditional careers. While they would help all workers, policies such as raising the minimum wage, paid sick days, paid family leave, fair scheduling, and pay transparency protections would have an especially large impact on women. Women currently make up two-thirds of workers who earn $10.10 or less per hour, and while 82 percent of high-wage working women have access to earned paid sick days, only 14 percent of low-wage working women do.* Policies such as these protect women’s jobs while allowing them to remain and excel in the workforce, to care for their families, and to fight for more fair and equitable wages.

Emily Baxter is a Research Associate for the Economic Policy team at the Center.

Author’s note: Men’s and women’s earnings are not comparable for preschool and kindergarten teachers. Throughout this article, data points not presented in graph form are based on the author’s calculations from Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by detailed occupation and sex,” available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat39.htm (last accessed April 2015) and Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employed persons by industry, sex, race, and occupation,” available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat17.htm (last accessed April 2015).

*Correction, April 14, 2015: This column has been corrected to clarify the demographic of workers with access to earned paid sick days. The correct statistic is that only 14 percent of low-wage working women have access to earned paid sick days.