Introduction and summary

These days, foreign policy and national security publications are filled with stark warnings about the demise of the U.S.-led rules-based international order—the system of global alliances and institutions that helped advance peace and prosperity for America and its allies in the aftermath of World War II. The Brexit vote in the United Kingdom; the election of President Donald Trump in the United States; new protest movements against global capitalism; the increasing strength of right-wing, anti-immigrant parties in Europe; and the rising power of nondemocratic regimes in China, Russia, and elsewhere are all seen as clear evidence that the old system of international relations is collapsing and may be permanently broken.1 With the post-war order under assault from both the nationalist right and the anti-imperialist left, observers fear that it is devolving into a fractured system of uncooperative nations led by populist or anti-democratic forces pursuing parochial interests while stoking hostility toward outsiders and fostering distrust of collective global action.

But are voters in Western societies experiencing a genuine attitudinal break with the old democratic order, or rather, are they going through a corrective period based on years of pent-up frustrations about economic and social conditions that have yet to improve?

Scholars and analysts have put forth numerous explanations for the ongoing disruption of global politics, ranging from middle class concerns about economic inequality and diminished social mobility to rising political tribalism and declining trust in major institutions.2 Behind each of these theories lie assumptions about voter attitudes driving the chaos seen in international affairs: Voters are angry and fearful. Voters dislike politicians and government. Voters are worried about uncontrolled immigration and increasing diversity. Social solidarity across groups is less important to voters than personal economic security. Liberal values of tolerance, pluralism, and individual liberty have given way to in-group loyalty, mutual suspicion, and support for anti-democratic solutions among key voting blocs. Failed military interventions have driven widespread skepticism about the use of force. Intergenerational unity and consensus remain elusive, as younger voters hold far different social values and norms about democracy and the economy than their elder peers.

Many of these assumptions about attitudinal trends are certainly true, particularly those related to voter anger, distrust of institutions, and concerns about the global economy and recent military actions.3 But much remains unexplored in terms of what voters believe and what they want their leaders to focus on today, particularly in the United States.

In the U.S. context, some of the important questions without clear answers include: Do voters want the United States to be more or less involved in solving global challenges and, if more involved, on which issues and in what manner? How do domestic priorities connect to international and security ones, if at all? What is the desired balance between military and nonmilitary action? Are there significant partisan divisions on foreign policy, and if so, is there any room for consensus across party lines? Do younger voters hold different priorities and values on foreign policy and national security issues than do older voters?

To better understand what precisely is motivating American voters today, the Center for American Progress, along with partners at public opinion research and strategic consulting firm GBAO, devised a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative research program to get at these and other questions about the fundamental values, beliefs, and priorities undergirding U.S. voter opinion on foreign policy and national security issues. Our goal with this particular project is not to advocate specific policy solutions or ideas but rather to get a clear reading about voters’ views in a number of areas. We hope that this far-reaching examination of voter attitudes will be of use to other researchers, practitioners, and policymakers as they devise their approaches to important foreign policy and national security issues.

Methodology and findings

Phase one of the study began in January 2019 with focus groups among a cross section of voters in Atlanta, Georgia, and Detroit, Michigan, followed by an online discussion with middle-of-the-road voters from across the country over several days to explore these issues in more depth. (see text box for methodological overview)

Methodological overview

GBAO conducted qualitative and quantitative research to support CAP’s exploration of public opinion on foreign policy. The qualitative phase included two parts: focus groups in Atlanta and Detroit, followed by an online QualBoard, a multiday discussion of the issues with voters from across the country.

Atlanta focus groups, conducted January 7, 2019:

Group 1: College educated, Republican-leaning men who support free trade

Group 2: Younger voters ages 28–36 who identify as Independents or weak partisans

Group 3: College educated Democrats who closely follow foreign policy news

Detroit focus groups, conducted January 9, 2019:

Group 1: Noncollege educated, Republican-leaning women who express isolationist views

Group 2: Younger voters ages 19–27 who identify as Independents or weak partisans

Group 3: Noncollege educated Democrats

The Qualboard was conducted January 15–17, 2019, and consisted of 28 participants who engaged in two sessions of questions and online conversation per day over a three-day period. All participants were registered voters who identify as Independents (21 out of 28) or weak partisans (3 weak Democrats, 4 weak Republicans) and who indicated that they closely follow foreign policy news. All participants were recruited from an online panel of registered voters and represent a mix of geographic areas, gender, race, age, and educational attainment.

The quantitative phase consisted of a poll of 2,000 registered voters that took place from February 25 to March 3, 2019. The poll was conducted online, using multiple nonprobability-based, opt-in web panels to balance out biases in any one-sample source. Sample demographics were balanced and weighted to match population estimates of registered voters from the U.S. Census Bureau’s November 2016 Current Population Survey. Interviews were conducted in English with self-identified registered voters.

The qualitative research revealed important gaps in voters’ basic understanding of U.S. foreign policy objectives and widespread confusion about what the nation is trying to achieve in the world. Voters in focus groups did not see an overarching principle, rationale, or clear set of goals in U.S. foreign policy. Questions emerged along the lines of: Why are we in the Middle East and not dealing with Russia and China? What exactly did we gain from years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan? Why can’t we balance our economic dealings with other countries to better benefit U.S. workers and businesses? Several participants wondered why the United States does not have a plan for economic and political success in the world like they perceive China and other competitors do.

Likewise, traditional language from foreign policy experts about “fighting authoritarianism and dictatorship,” “promoting democracy,” or “working with allies and the international community” uniformly fell flat with voters in our groups. Some participants questioned the idea that an international community actually exists. Democracy promotion reminded others of the 2003 Iraq War and the failures of the George W. Bush administration. When asked what the phrase “maintaining the liberal international order” indicated to them, all but one of the participants in our focus groups drew a blank. Voters across educational lines simply did not understand what any of these phrases and ideas meant or implied.

Subsequently, voters across party lines in our groups tried to make sense of a confusing set of issues by deferring to known mental models and shorthands based on their own personal values and experiences, such as: We should look out for ourselves first, then help others; we should be stronger and stop being weak; or we can’t do everything on our own, and we need to work with others to get things done. Given basic confusion about foreign policy, numerous voters in the focus groups and the online discussion reacted favorably to core elements of “America First” nationalism, primarily notions that the United States should stop being the world’s policeman and that it should focus more on its own problems rather than worrying about what is happening in other countries.

These qualitative findings, along with new concepts and theories, were then tested in phase two of the study: a nationally representative online survey of 2,000 registered voters conducted in February and March 2019. The results of the national survey are presented in detail in later sections of this report.

The national survey provides overwhelming evidence that American voters want the United States to be “strong at home” first and foremost to help it compete in the world. Voters across demographic lines express a clear desire for more investment in U.S. infrastructure, health care, and education—and less of an exclusive focus on military and defense spending—as part of a revamped foreign policy approach that gets America ready to compete with other countries. Large percentages of voters want the government to focus on “our own problems” as a means for bolstering America’s position economically and politically, especially in the face of rising challenges from nations such as Russia and China.

The findings in this survey suggest that American voters are not isolationist. Rather, voters are more accurately described as supporting “restrained engagement” in international affairs—a strategy that favors diplomatic, political, and economic actions over military action when advancing U.S. interests in the world. American voters want their political leaders to make more public investments in the American people in order to compete in the world and to strike the right balance abroad after more than a decade of what they see as military overextension.

In contrast to much of the debate among political leaders and foreign policy experts today, voters in this survey express little interest in the processes and tactics of foreign policy or the workings of international alliances and institutions. They generally support cooperation and engagement with allies, but these are not top-tier objectives on their own.

At the most basic level, voters want U.S. foreign policy and national security policies to focus on two concrete goals: protecting the U.S. homeland and its people from external threats—particularly terrorist attacks—and protecting jobs for American workers. They also support efforts to protect U.S. democracy from foreign interference, advance common goals with allies, and promote equal rights in other countries. But these are second-order preferences. In the hierarchy of concerns about foreign policy, terrorism and a strong economy are more immediate issues for voters than are efforts to advance democratic values around the world.

In the political arena, President Trump receives poor marks from American voters for his foreign policy stewardship—worse than his overall job approval ratings—although he performs better on the economy. Despite Trump’s unpopularity, several of the nationalist ideas embedded in his “America First” vision—including placing U.S. problems above those in other countries and making allies pay their fair share for security—receive strong support from his most ardent backers and the Republican base and lower but noticeable support from Independent and Democratic voters. His restrictive views on immigration, however, produce major divisions between Republican and Democratic voters, who remain far apart in their prioritization of immigration as an issue and on the scope of what they see as the appropriate U.S. response.

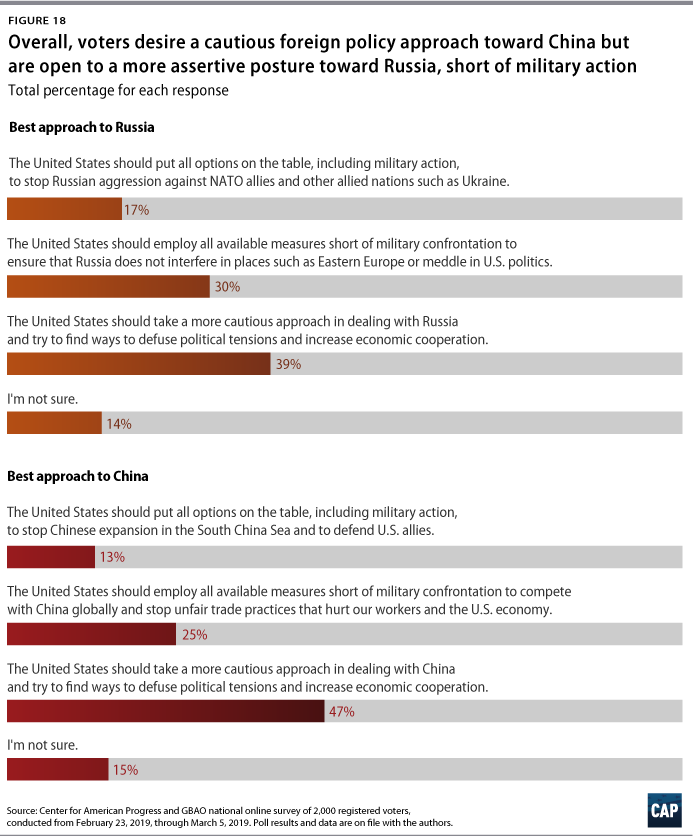

In terms of other countries, China is overwhelmingly viewed as America’s top competitor. Voters express a clear desire for a cautious approach to dealing with China, and pluralities of voters favor steps to defuse tensions and increase cooperation on political and economic grounds. Russia is viewed mostly as an enemy of the United States, but voters also prefer more caution than confrontation in dealing with Russia. Voters overwhelmingly reject putting military action on the table in dealing with both China and Russia. Although few participants in our focus groups said they were following the Mueller investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 elections, the survey shows that many voters believe protecting U.S. democracy from foreign interference should be a top foreign policy goal.

The study finds significant generational and partisan divides across multiple measures tested, including foreign policy goals, priorities, and beliefs about international engagement; the use of force; climate change and poverty; and “America First” attitudes.

Younger voters are much less committed to traditional international and military engagement than are their elder cohorts, and they are more in favor of global action on issues such as climate change, human rights, and basic living standards for all people. Younger voters are also far less committed than older voters to several “America First” sentiments, particularly those related to trade and immigration. At the same time, the survey finds that many Generation Z and Millennial voters hold no strong views whatsoever about any foreign policy or national security issue. Many of these youngest voters are entirely disengaged from foreign policy and national security news and debates and consequently hold few strong opinions on many issues.

In the partisan context, Democratic voter priorities lean more toward nonmilitary global action on issues such as combating climate change and reducing poverty, while Republican voter priorities are much more focused on stopping terrorist threats and reducing illegal immigration.

However, in perhaps the most important findings in the survey, voters across generational and partisan lines strongly desire more domestic investment in infrastructure, health care, and education to increase the United States’ global competitiveness rather than merely increasing military and defense spending. Voters across party lines also strongly agree that the United States faces new threats—including cyberattacks, chemical weapons, and drones—that require coordinated military and intelligence efforts with other countries.

None of these well-supported areas for action receive much public focus from foreign policy decision-makers and political leaders today, reflecting the divide between elite discourse and voter opinion on national security and global affairs issues.

The study also highlights how engagement with foreign policy news and developments, as well as measures of social trust—perceptions about the trustworthiness and reliability of other people—and media viewership, connect to a range of attitudes. Voters with low levels of foreign policy engagement and low social trust express much lower levels of strong agreement with statements about U.S. leadership in the world and multilateral actions to fight climate change and poverty and higher levels of strong agreement with actions focusing on home and domestic problems first. In addition, regular Fox News viewers express much higher levels of agreement than do non-Fox viewers on issues related to military engagement and prioritizing military spending, as well as on “America First” sentiments.

Another important observation from the project is that many of the categories and labels used in the past to describe different foreign policy camps no longer apply. Terms used to describe voters’ beliefs such as neoconservative, liberal interventionist, or isolationist do not adequately capture the complexity of attitudes and values that emerged in this project.

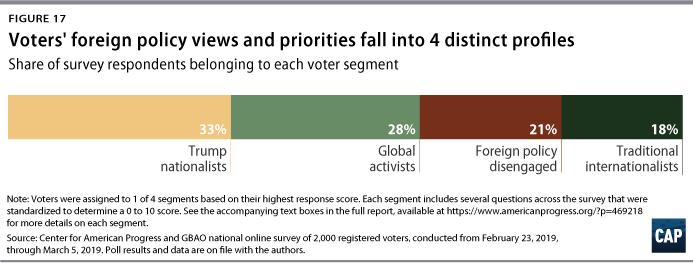

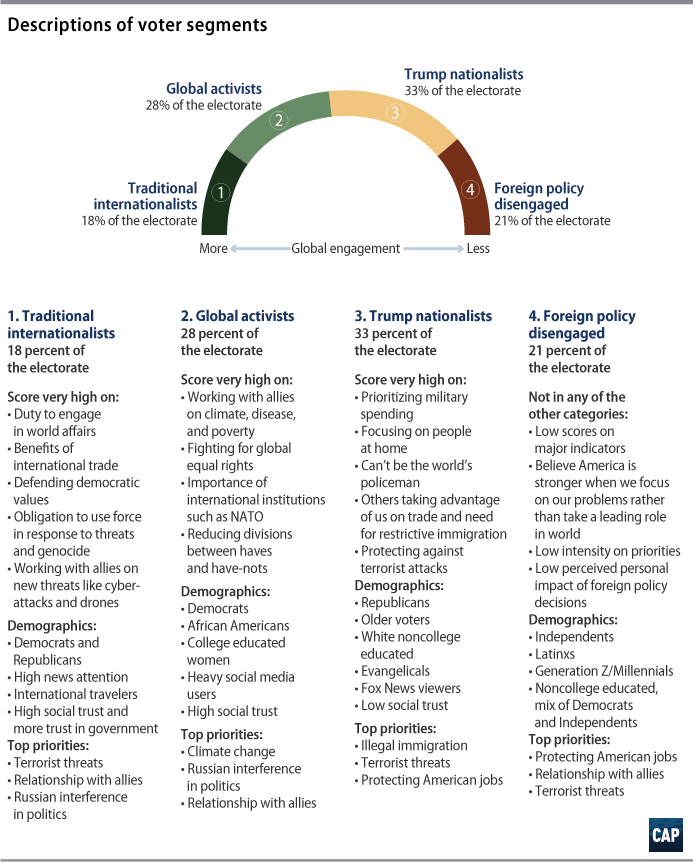

Based on responses to questions about goals, priorities, and attitudes tested throughout the survey, our project divided the electorate into four distinct groupings. One-third of American voters fall into what we label the “Trump nationalist” camp. Composed heavily but not exclusively of Republicans and regular Fox News viewers, this group is strongly in favor of prioritizing military spending and strongly against immigration and the United States acting as the world’s policeman.

Balancing this nationalist bloc are two kinds of voters more open to U.S. engagement in the world: “traditional internationalists” and “global activists.” A little less than one-fifth of the electorate, including a mix of Republican and Democratic, mostly older voters, may be described as “traditional internationalists.” These voters are the strongest believers in international engagement in a general sense and are the most committed to U.S. leadership in the world. Just less than 3 in 10 voters occupy what we call the “global activist” camp, a group that is heavily Democratic, very liberal, and well-educated. This group strongly favors diplomacy over military action and is very supportive of cooperative global actions on issues such as climate change, human rights, and poverty.

The final segment of the electorate—a little more than one-fifth—form the “foreign policy disengaged” bloc: Disproportionately younger, less educated, and less attentive to international developments, these voters lack strong opinions on most foreign policy issues and ideas.

These new categories described above should be just the start of a deeper and longer exploration of how U.S. public attitudes on foreign policy and national security have changed in the past decade. Given the dynamic and complicated geopolitical environment—and the shifting nature of American politics—it is likely that more major shifts in attitudes will be seen in the years to come.

But for now, American voters do not desire a full retreat from global affairs. They want to work with U.S. allies and international institutions to solve global challenges but only if the nation is also committed to putting its domestic house in order. They want to know that the United States is focused on its own economic and security needs first before tackling global problems it cannot control. Voters desire protection above other foreign policy goals—protection from harm and protection of U.S. jobs—and favor investment in domestic infrastructure and economic opportunities.

Put simply: American voters believe that America needs to be strong at home in order to be strong in the world.

This report is divided into several sections that can be read together or separately, including: the larger national and political landscape of voter views on foreign policy; voter goals and priorities for foreign policy; basic views about U.S. leadership and values; 20 attitudes defining voters’ foreign policy worldviews; social trust and Fox News effects on foreign policy views; profiles of the major groups in the electorate; and voter perceptions about which countries are America’s friends, enemies, and competitors. The full topline results, broken out by generation, are posted separately on the Center for American Progress website, and the full dataset is on file with the authors.

Summary of major findings

The Center for American Progress, in conjunction with GBAO, set out to better understand how voters today think about foreign policy and national security issues across a range of topics. Major findings from a nationally representative online poll of 2,000 registered voters that we conducted in February and March 2019 are discussed in the sections below.

Understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals and attention to news

- As indicated in focus groups, the survey finds high levels of uncertainty among voters about U.S. foreign policy goals. Decades after the end of the Cold War and 18 years after the terrorist attacks on the United States on 9/11, many voters want to know: What exactly are we trying to accomplish as a nation?

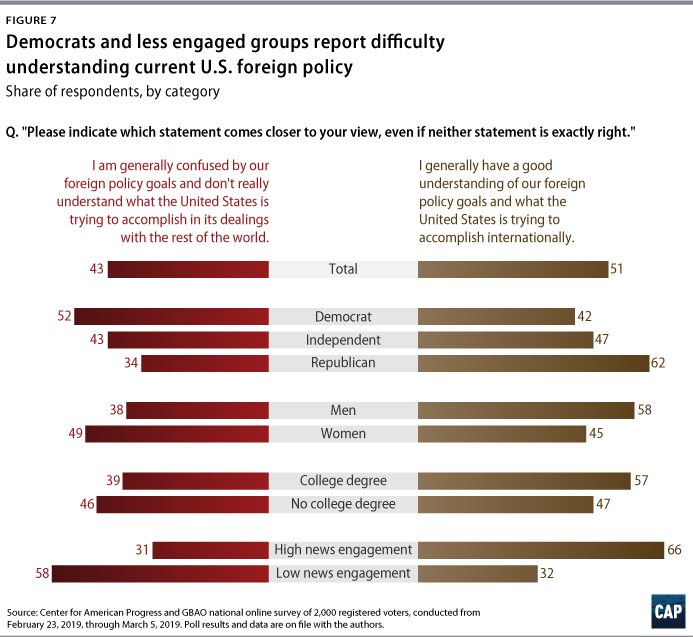

Asked to choose which of two statements comes closer to their own view, only a slight majority of voters, 51 percent, report, “I generally have a good understanding of our foreign policy goals and what the United States is trying to accomplish internationally,” while 43 percent say, “I am generally confused by our foreign policy goals and don’t really understand what the United States is trying to accomplish in its dealings with the rest of the world,” and another 6 percent are not sure.

Significant education differences emerge on this question. Nearly 6 in 10 college educated voters, those with a 4-year degree or higher, feel they generally have a good understanding of foreign policy goals, while 39 percent of these voters say they are generally confused. In comparison, only 47 percent of noncollege educated voters, those without a 4-year degree, say they have a good handle on what the United States is seeking to do with its foreign policy, with a nearly equal proportion, 46 percent, saying they are confused.

- In terms of foreign policy news, voters are somewhat split on how much attention they pay to international developments. Fifty-six percent of voters overall report that in a given week they either pay “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of attention to news and developments related to U.S. foreign policy and national security issues, while 44 percent say that their attention amounts to “some,” “not too much,” or “almost none” on these matters in a given week.

Democrats and Republicans report nearly identical levels of high attention (“a great deal” or “quite a bit”)—57 percent and 58 percent, respectively—with Independent voters well below at 43 percent.

A noticeable gender gap emerges on voter attention to news and developments on foreign policy and national security: 66 percent of men say they pay “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of attention to foreign policy news each week, compared with only 46 percent of women.

Top voter goals and priorities for foreign policy

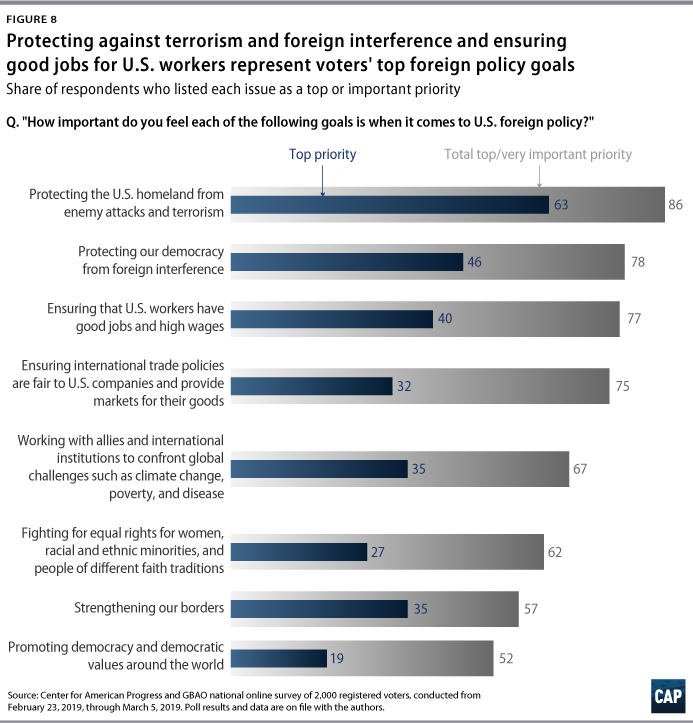

- Concerns about protecting the country from attacks and terrorism clearly dominate other important goals in voters’ minds. Nearly 90 percent of American voters say that “protecting the U.S. homeland from enemy attacks and terrorism” should be either a top or very important goal of U.S. foreign policy, with a full 63 percent of voters saying it should a top priority.

None of the other goals measured independently in the survey approaches this level of top priority in voters’ minds. Forty-six percent of voters say that “protecting our democracy from foreign interference” should be a top priority, and 40 percent feel similarly about a goal of “ensuring that U.S. workers have good jobs and high wages.”

At the bottom of the list of top priorities, 27 percent of voters overall believe that “fighting for equal rights for women, racial and ethnic minorities, and people of different faith traditions” should be a top priority goal, and only 19 percent feel similarly about “promoting democracy and democratic values around the globe.”

- Asked to choose the three most important foreign policy priorities over the next five years from a specific list, “protecting against terrorist threats from groups like ISIS or al-Qaeda” ranks at the top of the list, chosen by 40 percent of voters, followed closely by “protecting jobs for American workers” at 36 percent and “reducing illegal immigration” at 35 percent.

The study finds significant generational and partisan divides on issue priorities for the next five years, with younger voters and Democrats placing a much higher premium on combating global climate change and less of a priority on reducing illegal immigration than do older voters and Republicans.

Views of U.S. leadership in the world

- American voters have not rejected traditional internationalism, but they are clearly weary after decades of military intervention in the Middle East and desire more focus on domestic investments in infrastructure, education, and health care at home.

Voters are essentially divided, however, about the basic role of U.S. leadership in the world. Asked which statement comes closer to their view, a slight majority of voters, 51 percent, believe, “America is stronger when we take a leading role in the world to protect our national interests and advance common goals with other allies,” versus 44 percent who believe the opposite, that “America is stronger when we focus on our own problems instead of inserting ourselves in other countries’ problems,” with another 5 percent of voters not sure either way.

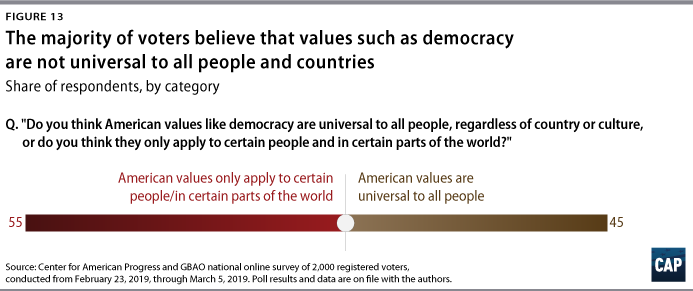

- In addition, voters express skepticism about claims that U.S. ideals and norms apply widely around the world. Asked, “Do you think American values like democracy are universal to all people, regardless of country, or do you think they only apply to certain people and in certain parts of the world?”, only 45 percent of voters believe these values are universal, while 55 percent say they are confined to certain parts of the world.

20 attitudes defining voters’ foreign policy views

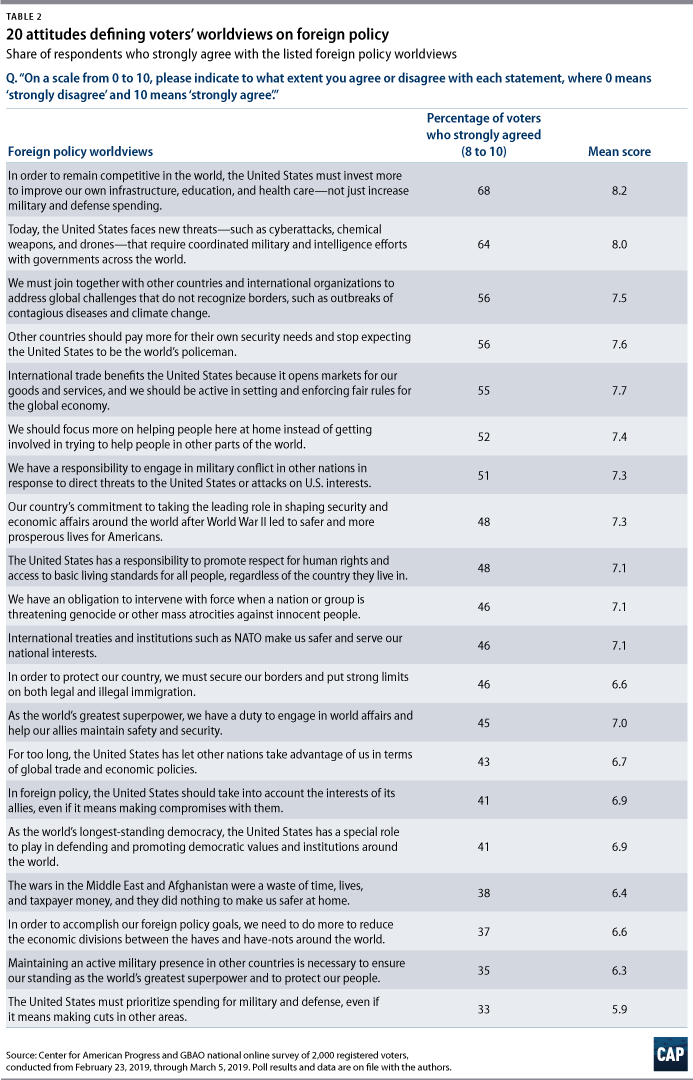

- The core of the survey comprises 20 attitudinal questions broken into four separate groupings related to: U.S. leadership in the world, the use of force, multilateral actions on global issues, and “America First” ideas. Voters were asked to rate each statement independently on a zero to 10 scale, with zero indicating that a respondent strongly disagrees with a statement and 10 meaning that a voter strongly agrees with a statement.

At the top of list—with 68 percent of voters strongly agreeing (a rating of 8–10) and a mean score of 8.2—is the idea: “In order to remain competitive in the world, the United States must invest more to improve our own infrastructure, education, and health care, not just increase military and defense spending.” At the very bottom of the list—with only 33 percent of voters strongly agreeing and a mean score of just 5.9—is the inverse notion: “The United States must prioritize spending for the military and defense, even if it means making cuts in other areas.”

Sixty-three percent of Generation Z/Millennial voters strongly agree with this top-rated statement about domestic investment, along with 65 percent of Generation X voters and 73 percent of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters. Likewise, 74 percent of Democrats; 64 percent of Independents; and 62 percent of Republicans express strong agreement with the idea of domestic investment to bolster America’s global competitiveness.

- As a complement to investing at home to make us more competitive globally, there is also broad agreement among voters about the importance of new threats in the world. Ranking second on the list, with 64 percent of voters strongly agreeing and a mean score of 8, is the statement: “Today, the United States faces new threats, such as cyberattacks, chemical weapons, and drones, that require coordinated military and intelligence efforts with governments across the world.” Sixty-two percent of Democrats, 52 percent of Independents, and 71 percent of Republicans strongly agree with a focus on emerging threats, as do majorities of Generation Z/Millennial voters at 53 percent, Generation X voters at 56 percent, and Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters at 78 percent.

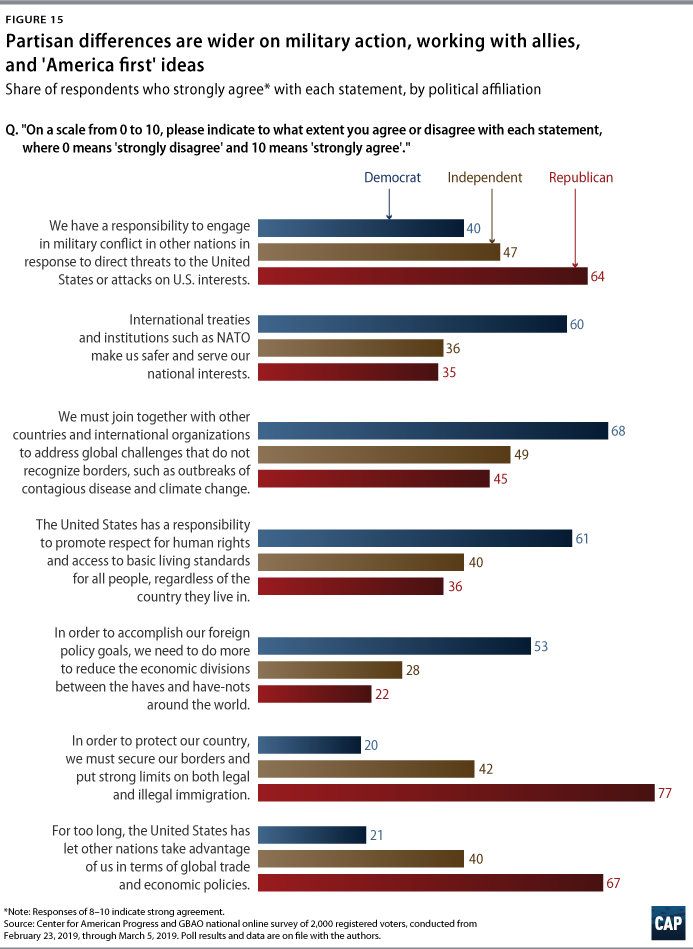

- Voters from the two major parties depart significantly from one another on statements related to prioritizing military spending, use of force, and international treaties and institutions. Some of the starkest partisan divides arise on core components of President Trump’s “America First” approach.

More than three-quarters of Republicans strongly agree with a very restrictive view on immigration—“In order to protect our country, we must secure our borders and put strong limits on both legal and illegal immigration”—compared with just one-fifth of Democrats. More than two-thirds of Republicans strongly believe, “For too long, the United States has let other nations take advantage of us in terms of global trade and economic policies,” versus around one-fifth of Democrats.

- Democrats and Independents do report more agreement with some aspects of Trump’s nationalism, though at lower levels than his most ardent backers. Forty-one percent of Democrats and 55 percent of Independents strongly agree that “we should focus more on helping people here at home instead of getting involved in trying to help people in other parts of the world,” along with 62 percent of Republicans. Forty-percent of Democrats also strongly agree that “other countries should pay more for their own security needs and stop expecting the United States to be the world’s policeman,” along with strong majorities of both Independents, at 55 percent, and Republicans, at 74 percent.

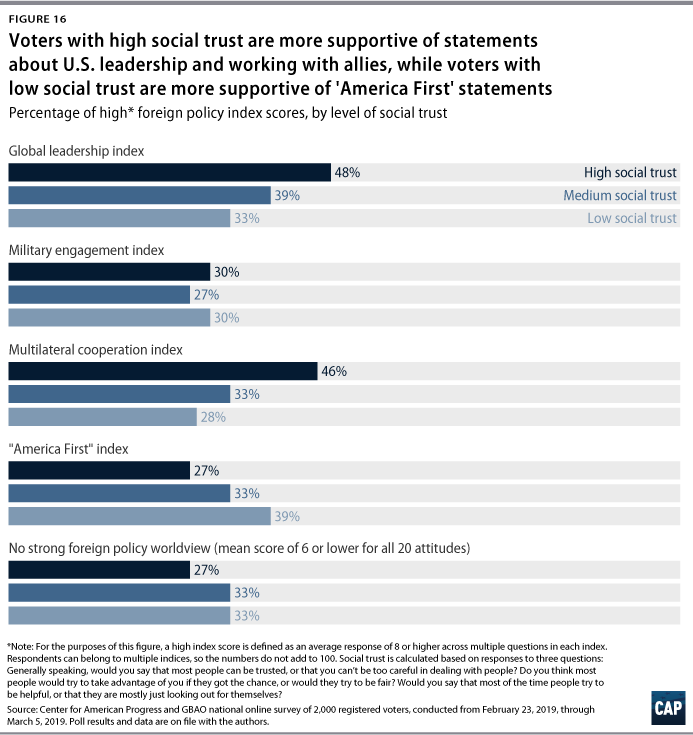

Social trust and Fox News effects

- Social trust indicators, first developed by the Pew Research Center, are also related to several dimensions of foreign policy engagement and attitudes in this survey.4 Voters with “high” social trust report higher levels of attention to foreign policy news and developments, higher levels of perceived personal impact and connections to people in other countries, and higher levels of agreement that U.S values are universal than do voters with “low” social trust. Voters with high social trust are also in much stronger agreement with ideas about U.S. leadership in the world and the need for international cooperation. Conversely, voters with low social trust are more likely to score highly on a number of “America First” sentiments.

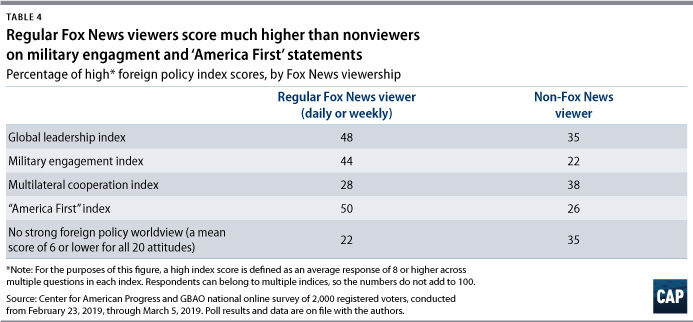

- Regular Fox News viewers are twice as likely as non-Fox viewers to score highly on our military engagement index—44 percent versus 22 percent, respectively—and nearly twice as likely to score highly on the “America First” index—50 percent versus 26 percent, respectively. (A high score on an index represents an 8 or greater average response across several statements in each category.)

The strongest relationship between Fox News viewership and foreign policy attitudes, however, is on the issue of immigration: 71 percent of regular Fox News viewers strongly agree that “in order to protect our country, we must secure our borders and put strong limits on both legal and illegal immigration,” compared with only 46 percent of voters overall.

Views of other countries

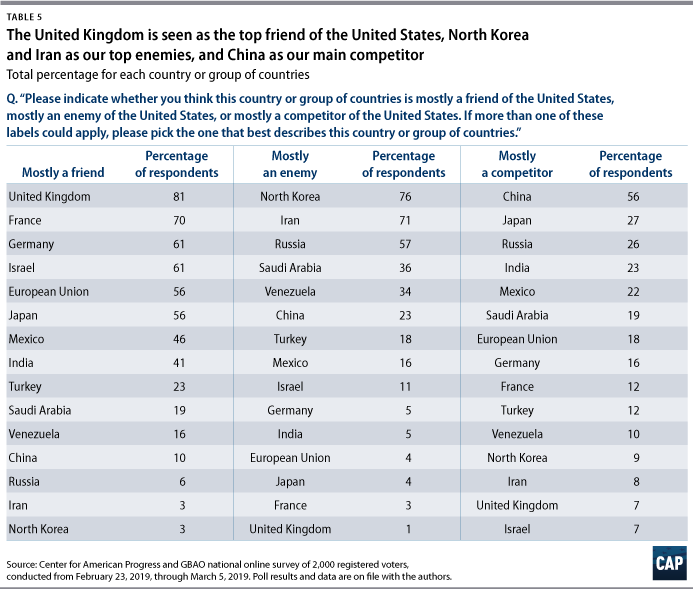

- The survey asked voters to rate a series of countries or group of countries as mostly a friend, mostly an enemy, or mostly a competitor of the United States. The “mostly a friend” list is topped by the United Kingdom at 81 percent, followed by France at 70 percent, Germany at 61 percent, Israel at 61 percent, the European Union at 56 percent, and Japan at 56 percent.

The “mostly an enemy” list is dominated by North Korea, at 76 percent, and Iran, at 71 percent, with Russia, at 57 percent, also being designated as mostly an enemy of the United States by a majority of voters. Thirty-six percent of voters describe Saudi Arabia as mostly an enemy of the United States as well.

China overwhelmingly emerges as America’s chief competitor in voters’ minds. Fifty-six percent of voters say China is mostly a competitor of the United States—the only nation labeled as “mostly a competitor” by a majority of voters.

- Despite Russia being viewed as mostly an enemy of the United States and China being seen as the United States’ chief global competitor, American voters strongly desire more caution in dealing with both of these countries and firmly reject a primarily military-based response.

National and political landscape of voter views on foreign policy

To examine the background for public discussions about foreign policy and national security policies, the study explored several dimensions of voter opinion on matters including job performance and assessment of President Trump’s leadership on these issues; voter engagement with foreign policy news and the primary sources for this information; and the perceived personal impact of foreign policy decisions made by the government.

These larger perceptions in turn shape a range of specific beliefs on international engagement, the use of force, global activism, and “America First” sentiments. In general, voters with higher levels of attention to foreign policy news and greater belief that foreign policy decisions affect their own lives express stronger support for U.S. leadership, measured use of force, and multilateral actions on key global issues. Conversely, voters who score low on both attention and perceived personal impact report greater ambivalence and lower levels of strong support on statements about international engagement, as well as higher levels of strong agreement with “America First” sentiments.

How is President Trump doing in terms of his leadership on foreign policy? Not well, according to most voters in the survey.

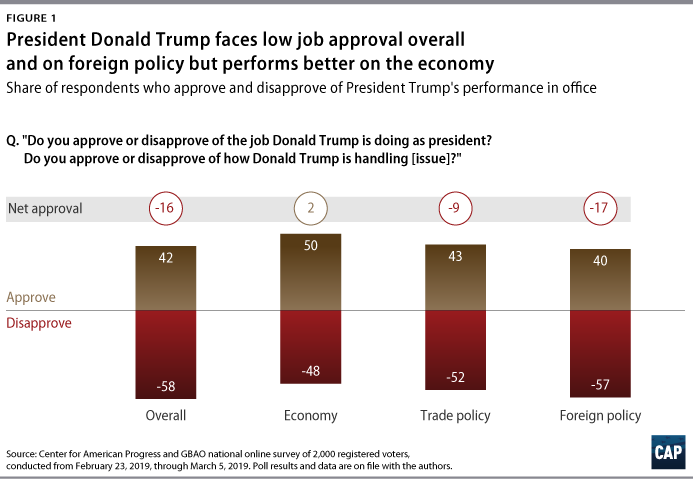

As Figure 1 shows, President Trump’s overall job approval rating remains negative, with 42 percent of voters approving of his job in office compared with 58 percent who disapprove of his performance. Trump’s approval specifically on foreign policy is even lower at 40 percent. There are sharp partisan divisions on the president’s job approval on foreign policy, however, with 90 percent of Democratic voters disapproving of his performance and 78 percent of Republicans approving of his efforts on foreign policy. Only 9 percent of Democrats approve of the president’s handling of foreign policy, while nearly one-fifth of Republicans disapprove of his efforts.

Voter intensity on this question breaks heavily against the president: 70 percent of Democrats strongly disapprove of President Trump’s handling of foreign policy, while only 43 percent of Republicans strongly approve of his actions in office. Independent voters clearly side with Democratic voter opinion on this front, with 62 percent of Independents disapproving of Trump’s handling of foreign policy and 34 percent approving.

President Trump receives slightly more positive ratings on trade policy and far more positive ratings for his handling of the economy. His approve-disapprove ratio on trade policy is 43 percent to 52 percent—a margin 7 percentage points stronger than his net overall job approval. Likewise, half of the national electorate approves of the president’s economic stewardship, while 48 percent disapproves. Republicans overwhelmingly approve of his handling of the economy at 88 percent, while nearly twice as many Democrats approve of his job on the economy as they do on foreign policy: 17 percent and 9 percent, respectively. Forty-five percent of Independents overall approve of President Trump’s performance on the economy, with a majority of Independent men, 51 percent, rating his economic stewardship favorably.

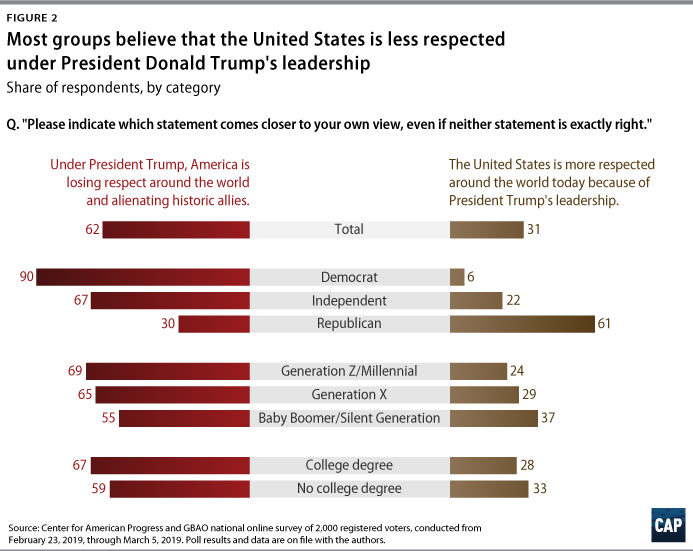

The survey also assessed whether voters believe America is more or less respected globally under President Trump. Voters were presented with two statements about the president’s leadership and asked to choose which one comes closer to their views even if neither statement is exactly right. Only 31 percent of voters overall believe, “The United States is more respected around the world because of President Trump’s leadership,” versus 62 percent who believe, “Under President Trump, America is losing respect around the world and alienating historic allies,” with 7 percent not sure.

As Figure 2 shows, noticeable partisan and generational differences emerge on the question of whether the United States is more or less respected around the world under President Trump. Ninety percent of Democrats and 67 percent of Independents say America is less respected, while 61 percent of Republicans say it is more respected. Majorities of all generational groups say that the United States is less respected under President Trump, with perceptions of more respect rising with age, from 24 percent among Generation Z/Millennial voters to 29 percent among Generation X voters to 37 percent among Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters. Noncollege educated voters are also slightly more likely than college educated voters to see America gaining more respect under President Trump’s leadership rather than less: 33 percent versus 28 percent, respectively.

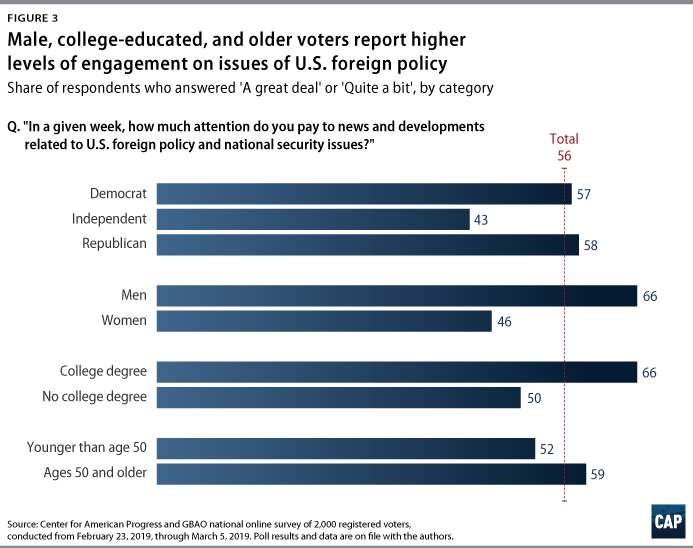

Turning to voters’ attention to foreign policy news, the study finds voters somewhat split on their self-reported attention to international developments. As Figure 3 highlights, 56 percent of voters report that in a given week they either pay “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of attention to news and developments related to U.S. foreign policy and national security issues, while 44 percent say that their attention amounts to “some,” “not too much,” or “almost none” on these matters in a given week.

Democrats and Republicans report nearly identical levels of high attention—57 percent and 58 percent, respectively—with Independent voters well below at 43 percent. A noticeable gender gap emerges on voter attention to news about and developments in foreign policy and national security: 66 percent of men say they pay “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of attention to foreign policy news each week, compared with only 46 percent of women. Likewise, the oldest bloc in the electorate, Baby Boomers and Silent Generation voters, report higher levels of weekly attention to news about foreign policy and national security than do their younger Generation Z, Millennial, and Generation X cohorts: 61 percent of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters pay a great deal or quite a bit of attention to foreign policy news, compared with just more than half of voters in younger generations.

Education divides on attention to foreign policy and national security news are stark. Two-thirds of college educated voters report paying “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of attention to news of world events, with a full 42 percent of post-graduates paying “a great deal” of attention. In comparison, noncollege educated voters are split 50-50 on attention to news on international developments, with white noncollege educated women reporting the lowest level of engagement on foreign policy news of all racial and education groups examined at 45 percent.

As mentioned above, voters with higher levels of attention to foreign policy news agree more strongly with a range of attitudinal statements related to U.S. leadership, military engagement, and multilateral actions than do those with lower levels of attention.

So where do voters get their information about international developments, foreign policy, and national security?

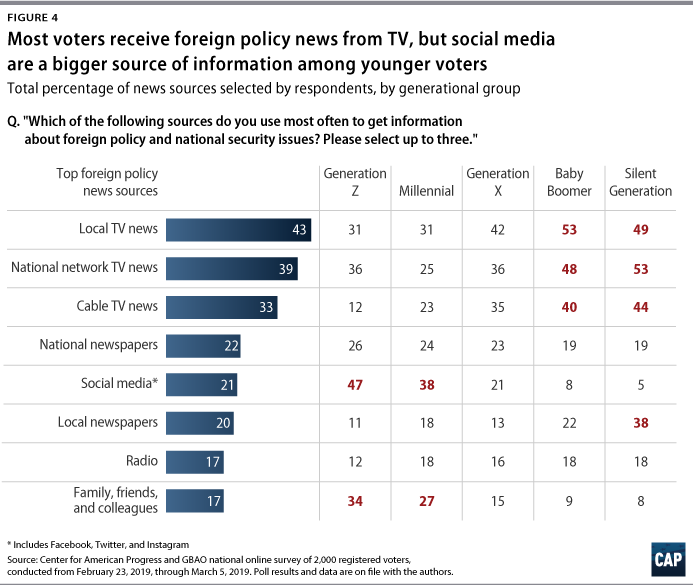

Interestingly, television news emerges as the primary source of information for voters overall, with “local television news” most used by voters, at 43 percent, as a source of foreign policy information, followed closely by “national network news” at 39 percent and cable television news at 33 percent. “Social media like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram” and “national newspapers online or in print” are basically on par among voters at 21 percent and 22 percent, respectively, with 17 percent of voters citing either “radio news or talk radio” or “family, friends, or colleagues” as sources of foreign policy news.

As highlighted in Figure 4, generational differences are pronounced in terms of where younger and older voters get their information about foreign policy and national security. For example, 53 percent of Baby Boomers cite local television news and an equal percentage of Silent Generation voters cite national network television news as their top source for information on these topics, while social media dominates among younger voters: 47 percent of Generation Z and 38 percent of Millennials use social media options as their top sources for foreign policy news. Younger generations also rely on local and network news for foreign policy information but at lower levels than older voters. In contrast, older voters report very low levels of social media use for foreign policy news and information.

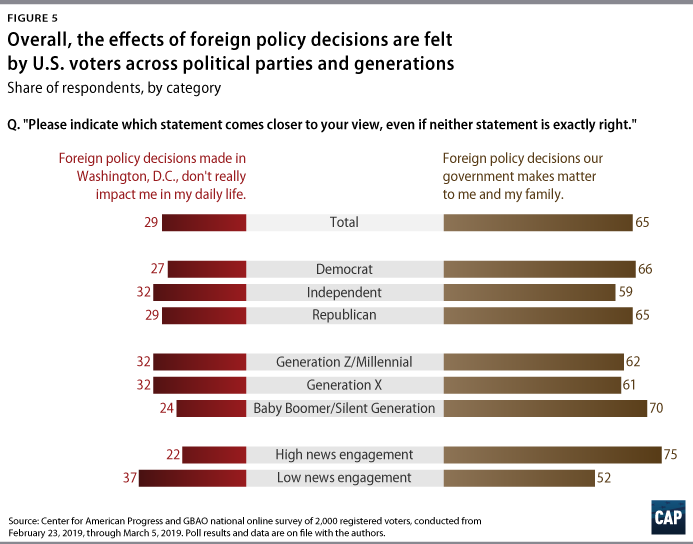

In terms of the perceived personal impact of U.S. foreign policy on people, nearly two-thirds of American voters believe that “foreign policy decisions our government makes matter to me and my family,” compared with less than 3 in 10 voters who believe that “foreign policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., don’t really impact me in my daily life” and another 6 percent who say they are not sure.

As Figure 5 shows, there are no significant demographic or partisan divides on perceived personal and family impact of foreign policy decisions, although perceived impact is slightly higher among older and more educated voters than among younger and less educated ones. However, perceived personal impact of foreign policy decisions is greatly shaped by a voter’s engagement with foreign policy news on a regular basis. By a 23-point margin, voters with higher levels of self-reported attention to foreign policy news issues are much more likely to say U.S. foreign policy decisions affect them and their families, at 75 percent, than are those voters with lower levels of foreign policy engagement, at 52 percent.

As with engagement on foreign policy news, perceptions of personal impact shape voters’ views on a range of foreign policy questions, particularly those related to U.S. leadership and multilateralism: Lower perceived personal impact of U.S. foreign policy decisions correlates to lower agreement with statements about international engagement and cooperative global efforts on things like climate change, poverty, disease, and the protection of human rights.

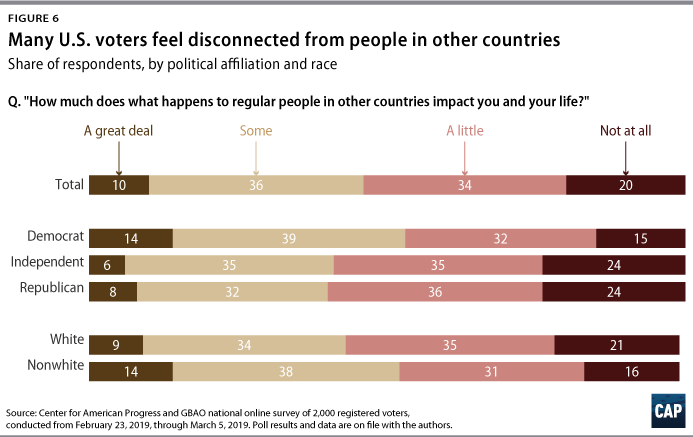

Although a majority of American voters believe that foreign policy decisions made by the government have an impact on their own lives, voters do not feel particularly affected by what is happening to people in others parts of the world.

Asked, “How much does what happens to regular people in other countries impact you and your life?”, only 10 percent of voters say “a great deal,” with another 36 percent saying “some.” A majority of voters believe that what happens to people in other countries impacts them just “a little” or “not at all.” As highlighted in Figure 6, African American and Hispanic voters are much more likely than white voters to say that what happens to regular people in other countries impacts their own lives. Likewise, a majority of Democrats believe that what happens to those in other countries has “a great deal” or “some” influence in their own lives, compared with nearly 6 in 10 Independents and a similar percentage of Republicans who say it impacts them only “a little” or “not at all.”

As with perceptions of the personal impact of U.S. foreign policy decisions on people’s lives, views about the connections between American voters and those in other countries are heavily shaped by ones’ overall attention to foreign policy news: Voters with high levels of attention to foreign policy news are much more likely than those with lower levels of attention, at 52 percent and 39 percent, respectively, to believe that what happens to regular people in other countries impacts them at least somewhat.

Foreign policy goals and priorities

As we learned in the qualitative phase of this project, American voters across demographic and partisan lines express confusion about the specific goals and purposes of U.S. foreign policy and national security policies. Decades after the end of the Cold War and 18 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, many voters are still asking: What exactly are we trying to accomplish as a nation?

The survey confirms high levels of uncertainty about U.S. goals abroad among an array of voters. Asked to choose which of two statements comes closer to their own view, only a slight majority of voters, 51 percent, report, “I generally have a good understanding of our foreign policy goals and what the United States is trying to accomplish internationally,” while 43 percent say, “I am generally confused by our foreign policy goals and don’t really understand what the United States is trying to accomplish in its dealings with the rest of the world,” and another 6 percent are not sure.

As seen in Figure 7, there is some partisan dimension to these responses, most likely reflecting divergent views of President Trump’s leadership: 62 percent of Republicans say they have a good understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals, while 52 percent of Democrats say they are generally confused by U.S. foreign policy goals. However, these divisions are nowhere near as stark as opinions about President Trump overall and his foreign policy specifically. This suggests that voters across political lines are genuinely confused about what the United States is trying to accomplish internationally and are not just aligning with party labels.

For example, we find significant education and gender differences on responses to this question. Nearly 6 in 10 college educated voters feel they generally have a good understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals, while 39 percent of college educated voters say they are generally confused. In comparison, only 47 percent of noncollege educated voters say they have a good handle on what the United States is seeking to do with its foreign policy, while a nearly equal proportion say they are confused. Additionally, men are much more likely than women to say that they have a good understanding of foreign policy goals. By a 20 percent margin, more men say they generally have a good understanding of U.S. goals than are confused about them; by a 4 percent margin, more women say they are generally confused by what the country is trying to accomplish in the world than have a good understanding of foreign policy goals.

Levels of engagement with foreign policy news and developments and foreign travel also shape perceptions about U.S goals among voters. By a 35 percent margin, voters who pay a great deal or quite a bit of attention to foreign policy news more often feel they generally have a good understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals, while voters with low levels of attention to foreign policy news feel more confused about U.S. goals internationally, by a 26 percent margin. Understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals is also higher among those who have traveled internationally in recent years: Roughly 6 in 10 voters, or 57 percent, who say they have traveled overseas in the past five years feel they have a good understanding of foreign policy goals, compared with only 43 percent of voters who have never traveled outside of the country.

As with the patterns on attention to news and the perceived personal impact of foreign policy decisions, voters with more confusion about U.S. foreign policy goals in turn express lower levels of agreement with a range of international and military engagement concepts.

What are voters’ desired goals for U.S. foreign policy and national security? The study explored this question using two different measures, including an independent ranking of specific goals and a separate test of major priorities for the next five years.

Asked, “How important do you feel each of the following goals is when it comes to U.S. foreign policy?”, concerns about protecting the country from attacks and terrorism clearly dominate other important goals in voters’ minds. Figure 8 presents the cumulative ratings of these different goals based on the percentage of voters rating each item as a “top priority” in the darker shade and the total percentage of voters rating each one as a combined “top priority” or “very important priority” in the lighter shade. As seen, nearly 90 percent of American voters say that “protecting the U.S. homeland from enemy attacks and terrorism” should be either a top or very important goal of U.S. foreign policy, with a full 63 percent of voters saying it should be a top priority.

This finding demonstrates that the shadow of the 9/11 attacks and its aftermath still looms large in the minds of many Americans, and terrorism remains an enduring issue for a large majority of voters.

None of the other goals measured in the survey approaches this level of top priority in voters’ minds. Forty-six percent of voters say that “protecting our democracy from foreign interference” should be a top priority, and 40 percent feel similarly about a goal of “ensuring that U.S. workers have good jobs and high wages.” Roughly one-third of voters give top priority ratings to goals around trade, working with allies, and strengthening U.S. borders. At the bottom of the list of top priorities, 27 percent of voters overall believe “fighting for equal rights for women, racial and ethnic minorities, and people of different faith traditions” should be a top priority goal; only 19 percent feel similarly about “promoting democracy and democratic values around the globe.”

Interestingly, we find more partisan agreement about major foreign policy goals than might be expected given the large political divides in the country. These findings suggest that there is a decent foundation for building a new foreign policy consensus that reaches across partisan and generational divides.

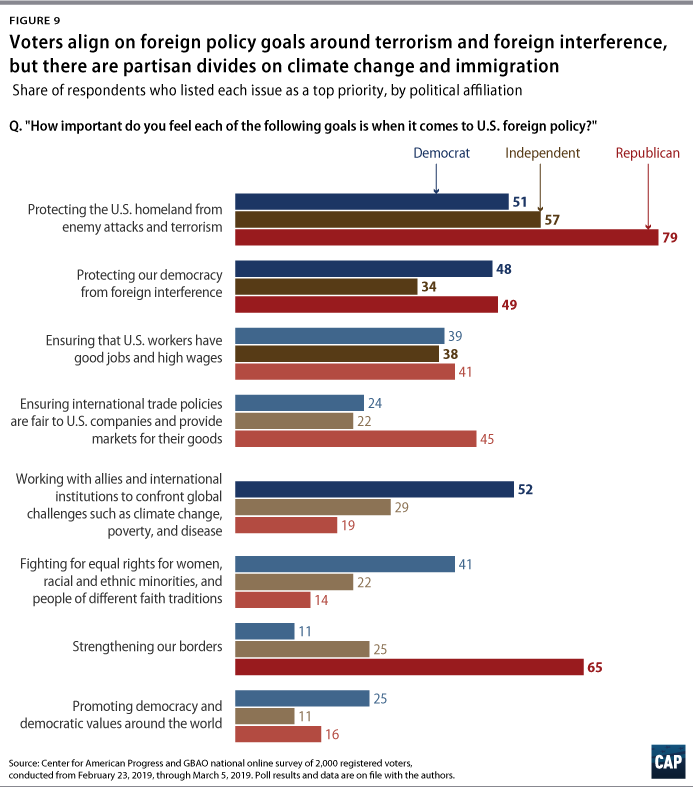

Although there are some differences in the degree of perceived priority on some items—particularly on terrorism—Republicans, Independents, and Democrats mainly agree about the importance of “protecting the U.S. homeland from enemy attacks and terrorism,” “protecting our democracy from foreign interference,” and “ensuring that U.S. workers have good jobs and high wages.” (see Figure 9)

Beyond these areas of general consensus, however, significant partisan differences arise on other dimensions of U.S. foreign policy. For example, Democrats place a much higher priority than do Republicans on specific global issues such as climate change and equal rights and a much lower priority on border protection. Fifty-two percent of Democrats say that “working with allies and international institutions to confront global challenges like climate change, poverty, and disease” should be a top priority for the country compared with only 19 percent of Republicans. Forty-one percent of Democrats say that fighting for equal rights globally should be a top priority versus 14 percent of Republicans. In contrast, only 11 percent of Democrats feel that “strengthening our borders” should be a top national priority compared with nearly two-thirds of Republicans. (see Figure 9)

In a separate exercise in the survey, we presented voters with a list of 12 specific items and asked them, “Which three of the following issues should be the top priorities for U.S. foreign policy in the next five years?”

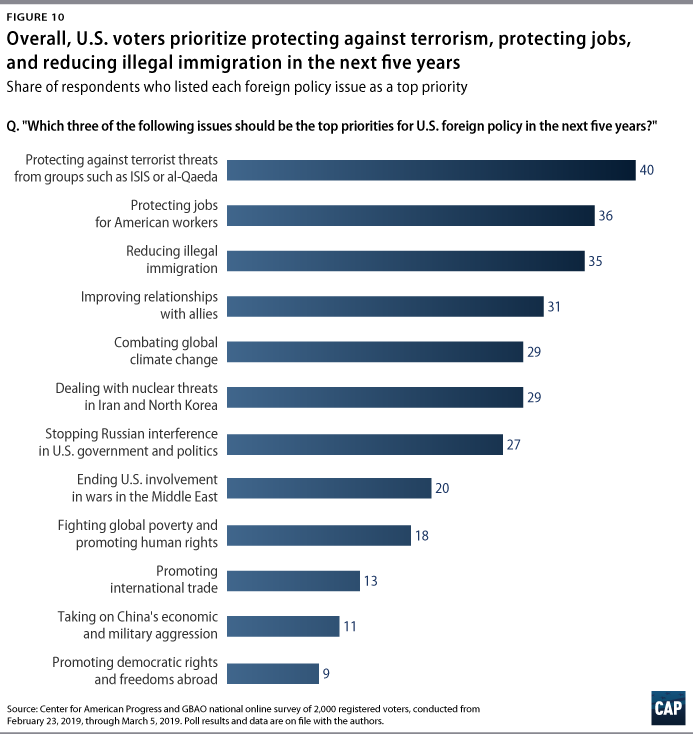

As Figure 10 highlights, voters are concerned with a number of emerging issues in the foreign policy arena, with “protecting against terrorist threats from groups like ISIS or al-Qaeda” at the top of the list of priorities, chosen by 40 percent of voters, followed closely by “protecting jobs for American workers” at 36 percent and “reducing illegal immigration” at 35 percent. Roughly 3 in 10 voters also choose as top priorities issues such as “improving relationships with allies,” “combating global climate change,” “dealing with nuclear threats in Iran and North Korea,” and “stopping Russian interference in U.S. government and politics.”

Other issues such as “fighting global poverty and promoting human rights” and “promoting democratic rights and freedoms abroad” fall further down the list of voter priorities for the next five years. Although these other issues are clearly important foreign policy objectives, in voters’ minds they do not rise to the level of ideas centered on protection: protecting the homeland from attack, protecting people against terrorism, and protecting American jobs.

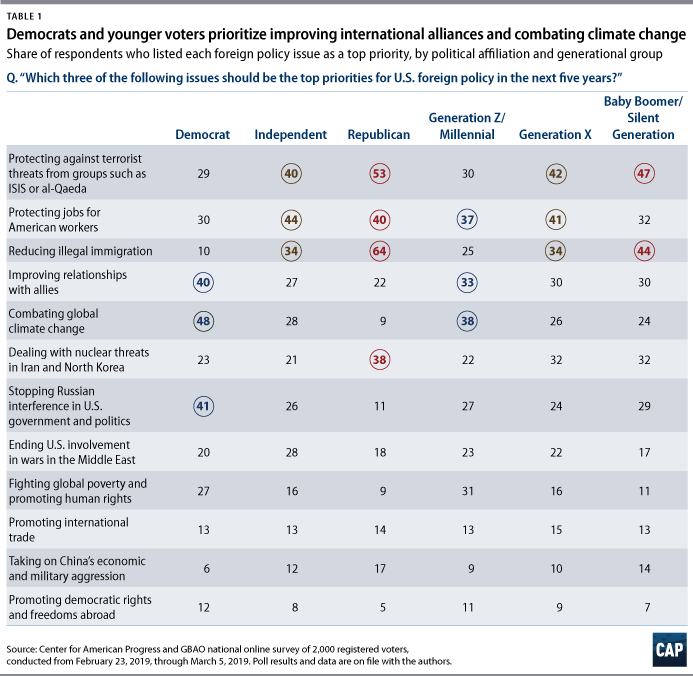

The survey reveals significant generational and partisan divides on issue priorities for the next five years, with younger voters and Democrats placing a much higher premium on combating global climate change—and less of a priority on reducing illegal immigration—than do older voters and Republicans. As seen in Figure 1, which breaks out the top three issue priorities for each designated group, 48 percent of Democrats choose “combating global climate change” as their top issue priority, while 64 percent of Republicans place “reducing illegal immigration” at the top of their list. “Stopping Russian interference in U.S. government and politics” and “improving relationships with allies” round out Democrats’ top three issue priorities, but these are priorities for only around one-tenth and one-fifth of Republicans, respectively.

Looking at generational differences on priorities for the next five years, combating climate change rises to the top of the issue list for Generation Z/Millennial voters, chosen by 38 percent, followed by protecting jobs for Americans and improving relationships with allies. In comparison, protecting the U.S. from terrorist threats and reducing illegal immigration are much more important issues for both Generation X and Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters.

Basic views on U.S. leadership and values

Getting to the heart of the debate about whether American voters favor retrenchment in global affairs or still desire a leading role for the United States in the world, this study returns a mixed verdict. Voters overall have not become isolationists nor are they unified in support of robust U.S. leadership in the world.

Based on the results of this survey, the bulk of American voters today are adherents of “restrained engagement”—an approach that favors domestic investments that help America remain competitive in the world and prioritizes diplomatic, political, and economic solutions over a military-first approach to global security challenges. American voters have not rejected traditional internationalism, but they are clearly weary after decades of military intervention in the Middle East and elsewhere and desire a focus on investment priorities geared more toward domestic infrastructure and the economic opportunities of Americans.

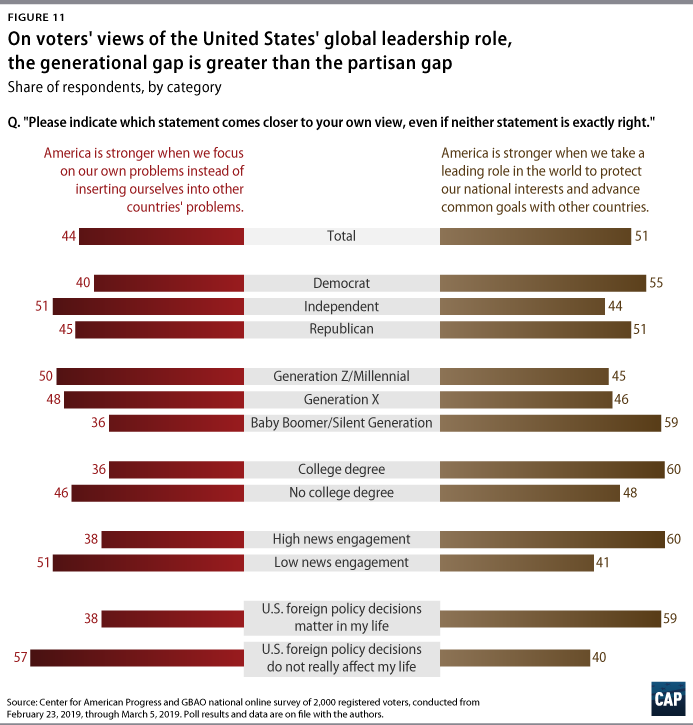

In one of the most important measures in the survey, voters are essentially divided about the basic role of U.S. leadership in the world. Asked which statement comes closer to their view, a slight majority of voters believe that “America is stronger when we take a leading role in the world to protect our national interests and advance common goals with other allies,” versus 44 percent who believe the opposite, that “America is stronger when we focus on our own problems instead of inserting ourselves in other countries’ problems,” with another 5 percent of voters not sure either way.

As seen in Figure 11, there are big generational and educational splits on this core question about whether America is stronger by taking a leading role in the world or by focusing on its own problems. Pluralities of Generation Z/Millennial and Generation X voters prefer a focus on domestic problems—50 percent and 48 percent, respectively—while a clear majority of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters, 59 percent, want to see America take a leading role in the world. Noncollege educated voters are basically split on the question, with many leaning toward a focus on domestic problems, while college educated voters break strongly in the direction of global leadership, 60 percent to 36 percent.

Interestingly, we find no real partisan differences on this basic measure of U.S. leadership: 55 percent of Democrats and 51 percent of Republicans believe that America should take a leading role in the world. Independents are the real outliers here, with 51 percent saying America is stronger when it focuses on its own problems.

Attention to foreign policy and perceived impact of foreign policy decisions also shape responses to this question: Strong majorities of those with high levels of attention to foreign policy news and agreement that foreign policy decisions impact their lives believe that America is stronger when it is taking a leading role in the world. Conversely, majorities of those with low levels of attention and little perceived personal impact believe the country is stronger when it focuses on its own problems first.

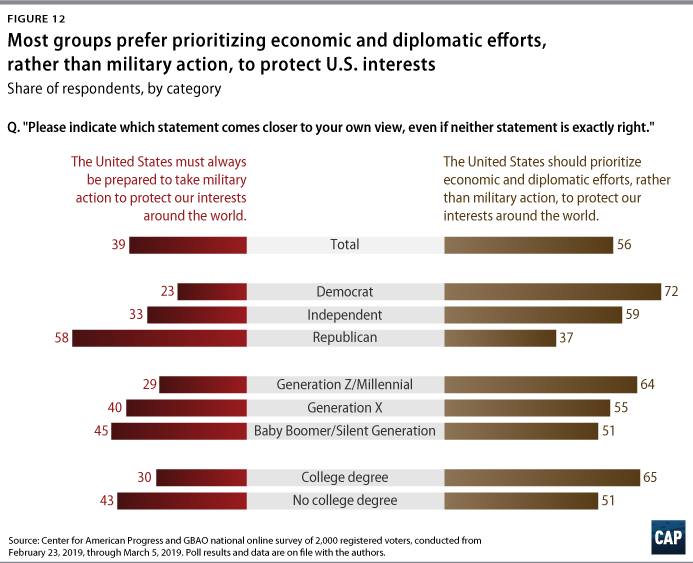

In a separate paired statement test, 56 percent of voters prefer the idea that “the United States should prioritize economic and diplomatic efforts, rather than military action, to protect our interests around the world,” versus 39 percent who believe that “the United States must always be prepared to take military action to protect our interests around the world,” with 5 percent unsure.

Looking at trends in Figure 12, majorities of voters across all generational groups favor prioritizing economic and diplomatic efforts over military action, with support for always being prepared for military action 16 percentage points higher among the oldest voters than among the youngest ones. Large majorities of Democrats, at 72 percent, and Independents, at 59 percent, choose economic and diplomatic efforts over military action, while nearly 6 in 10 Republicans prefer to always keep military action on the table. College educated voters also favor diplomacy over military action by a wide margin, 65 percent to 30 percent, while noncollege educated voters favor diplomacy by a smaller margin, 51 percent to 43 percent.

In terms of values, voters express skepticism about claims that U.S. ideals and norms apply widely around the world. Asked, “Do you think American values like democracy are universal to all people, regardless of country, or do you think they only apply to certain people and in certain parts of the world?”, only 45 percent of voters believe these values are universal, while 55 percent say they are confined to certain parts of the world. No real partisan differences emerge on this question, but older voters lean more heavily toward the idea that democratic values are not universal, perhaps reflecting their formative experiences with World War II and the Cold War.

20 attitudes defining voters’ foreign policy worldviews

The core of the survey comprises 20 attitudinal questions broken into four separate groupings: U.S. leadership in the world, the use of force, multilateral actions on global issues, and “America First” ideas. Voters were asked to rate each statement independently on a zero to 10 scale, with zero indicating that a respondent strongly disagrees with a statement and 10 meaning that a respondent strongly agrees with a statement.

Table 2, on the next page, lays out the total responses to the 20 attitudes, ranked by the total percentage of voters agreeing with each idea in the 8–10 range—the strongest level of agreement—along with the overall mean level of agreement for each item based on the zero to 10 scale. In general, we find relatively low levels of strong disagreement with these ideas, so this rank ordering allows us to differentiate those foreign policy and national security concepts with higher levels of strong agreement from those with lower levels of strong agreement.

At the top of the list, with 68 percent of voters strongly agreeing and a mean score of 8.2, is the idea: “In order to remain competitive in the world, the United States must invest more to improve our own infrastructure, education, and health care, not just increase military and defense spending.” And at the very bottom of the list—with only 33 percent of voters strongly agreeing and a mean score of just 5.9—is the inverse notion: “The United States must prioritize spending for the military and defense, even if it means making cuts in other areas.”

There is broad agreement with the statement about making American stronger at home to be more competitive abroad. Voters across party and generational lines clearly believe that to be strong in the world, the United States should do more to take care of key domestic needs and not just increase military and defense spending. Sixty-three percent of Generation Z/Millennial voters strongly agree with this top-rated statement, along with 65 percent of Generation X voters and 73 percent of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters. Likewise, 74 percent of Democrats, 64 percent of Independents, and 62 percent of Republicans express strong agreement with the idea of domestic investment to bolster America’s global competitiveness.

In contrast, the concept of prioritizing military and defense spending above other domestic programs receives much lower levels of strong agreement, with massive partisan and generational differences emerging on this indicator. Only 20 percent of Democrats and 25 percent of Independents strongly agree with the idea of prioritizing military and defense spending above other domestic considerations compared with a full 50 percent of Republicans. Similarly, strong support for prioritizing defense spending increases with age, from a low of 24 percent among Generation Z/Millennial voters to 30 percent among Generation X voters to nearly half of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters, at 49 percent.

As a complement to investing at home to make the nation more competitive globally, a broad section of American voters also want U.S. foreign policy decision-makers to focus on emerging threats in the world. Ranking second on the list, with 64 percent of voters strongly agreeing, is the statement: “Today, the United States faces new threats—such as cyberattacks, chemical weapons, and drones—that require coordinated military and intelligence efforts with governments across the world.” Sixty-two percent of Democrats, 52 percent of Independents, and 71 percent of Republicans strongly agree with a focus on emerging threats, as do majorities of Gen Z/Millennial voters, at 53 percent; Gen X voters, at 56 percent; and Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters, at 78 percent.

Beyond domestic investment and new threats, the study finds several ideas with broad partisan agreement—mainly related to U.S. leadership in the world—and others with more substantial partisan divides, particularly on indicators related to military engagement, multilateral action on global issues, and “America First” ideas and immigration.

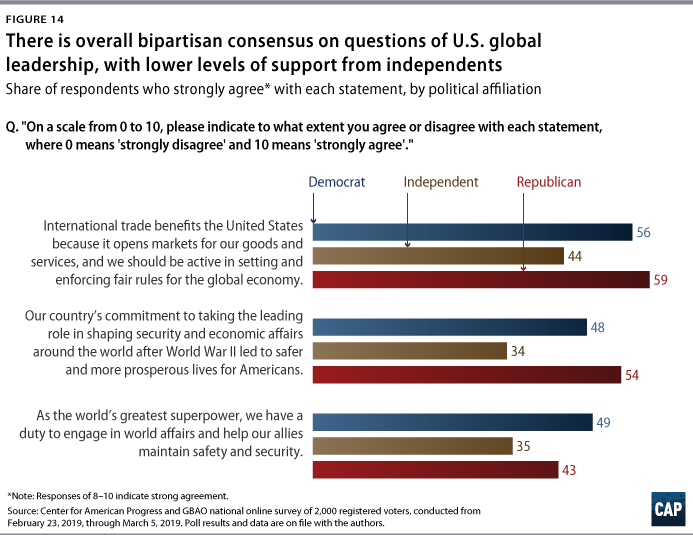

On the bipartisan consensus side, majorities of both Democrats, at 56 percent, and Republicans, at 59 percent, strongly agree with this statement on shaping trade and the economy: “International trade benefits the United States because it opens markets for our goods and services, and we should be active in setting and enforcing fair rules for the global economy.” Nearly half of Democrats, at 48 percent, and a majority of Republicans, at 54 percent, also strongly agree with a defense of the post-war order described at the outset of the report: “Our country’s commitment to taking the leading role in shaping security and economic affairs around the world after World War II led to safer and more prosperous lives for Americans.” And more than 4 in 10 Republicans and almost half of Democrats express strong agreement that “as the world’s greatest superpower, we have a duty to engage in world affairs and help our allies maintain safety and security.” (see Figure 14)

It should be noted that on each of these items, fewer Independent voters express strong agreement with statements about U.S. leadership in the world than do Democrats and Republicans, who are more aligned on these questions.

On other measures listed in Table 2, voters from the two major parties depart significantly from one another. In addition to the partisan divide on prioritizing military spending, nearly two-thirds of Republicans strongly agree that, “We have a responsibility to engage in military conflict in other nations in response to direct threats to the United States or attacks on U.S. interests,” compared with 40 percent of Democrats. (see Figure 15) Interestingly, 47 percent of voters from both parties express alignment on the country’s obligation to intervene with force to stop genocide or other mass atrocities, but the divide on the wisdom of military engagement in a larger sense remains apparent.

Partisan gaps are even wider on statements focused on multilateral action on global issues. In the year of the 70th anniversary of the creation of NATO, the study finds 60 percent of Democrats strongly agreeing with the statement, “International treaties and institutions like NATO make us safer and serve our national interests,” compared with only 35 percent of Republicans and 36 percent of Independents who think similarly.

Likewise, more than two-thirds of Democrats strongly agree that, “We must join together with other countries and international organizations to address global challenges that don’t recognize borders, like outbreaks of contagious disease and climate change,” compared with less than half of Republicans and Independents.

Issues involving human rights and fighting economic inequality produce equally large partisan divides in terms of strength of voter agreement. More than 6 in 10 Democrats strongly agree with the statement: “The United States has a responsibility to promote respect for human rights and access to basic living standards for all people, regardless of the country they live in.” In comparison, only 36 percent of Republicans and 40 percent of Independents strongly agree with that sentiment. And although a majority of Democrats, 53 percent, strongly agree that “in order to accomplish our foreign policy goals, we need to do more to reduce the economic divisions between the haves and have-nots around the world,” only 22 percent of Republicans and 28 percent of Independents express similar strong agreement. (see Figure 15)

Some of the starkest partisan divides arise on core components of President Trump’s “America First” approach. For example, more than three-quarters of Republicans strongly agree with a very restrictive view on immigration—“In order to protect our country, we must secure our borders and put strong limits on both legal and illegal immigration”—compared with just one-fifth of Democrats. Similarly, more than two-thirds of Republicans strongly believe that “for too long, the United States has let other nations take advantage of us in terms of global trade and economic policies,” versus around one-fifth of Democrats.

On other, less combative aspects of the president’s nationalist agenda—particularly ideas related to being strong at home and making allies pick up their share of security—Democrats and Independents show more agreement, although at lower levels than his most ardent backers. Forty-one percent of Democrats and 55 percent of Independents strongly agree that “we should focus more on helping people here at home instead of getting involved in trying to help people in other parts of the world,” along with 62 percent of Republicans. Forty percent of Democrats also strongly agree that “other countries should pay more for their own security needs and stop expecting the United States to be the world’s policeman,” with strong majorities of both Independents, at 55 percent, and Republicans, at 74 percent, aligned on this idea.

Additionally, both Democratic and Independent voters express greater concern about interventions in the Middle East than do Republicans. Forty-four percent of Democrats and 41 percent of Independents strongly agree with a sharply worded criticism: “The wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan were a waste of time, lives, and taxpayer money, and they did nothing to make us safer at home,” compared with less than one-third of Republicans.

On the age front, we find clear evidence of generational differences on numerous ideas undergirding U.S. foreign policy, as well as some continuity of opinions across generations.

Table 3 presents several indices designed to measure aggregate levels of strong agreement across the 20 attitudes, which are combined into four categories: global leadership, military engagement, multilateral cooperation, and “America First.” The numbers reported in the table represent the proportion of each age group registering a high score, defined as an average of 8 or higher on the zero to 10 scale across multiple questions included in each area. These groupings are not exclusive, meaning that people can be categorized in multiple groups depending on their attitudes. The table also designates a fifth category labeled “no strong foreign policy worldview,” which shows the proportion of each age group reporting an average of 6 or lower across all of the statements, indicating no strong opinions about any of the foreign policy questions assessed.

As seen in Table 3, by double-digit margins, Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters express stronger agreement than Generation Z/Millennial voters on both the global leadership and military engagement indices, as well as on the “America First” index. Twenty-nine percent of Generation Z/Millennial voters rate a high score on the global leadership index, compared with 35 percent of Generation X voters and half of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters. Similarly, only one-fifth of Generation Z/Millennial voters and one-quarter of Generation X voters rate a high score on military engagement, versus nearly 4 in 10 of the oldest voting bloc.

The largest gap between the youngest and oldest voters is seen on the “America First” index: Only 22 percent of Generation Z/Millennial voters rate a high score on the composite “America First” index, compared with 32 percent of Generation X voters and 44 percent of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters.

There is more alignment between generations on issues involving multilateral action to solve global problems, with 34 percent of Generation Z/Millennial voters, 32 percent of Generation X voters, and 37 percent of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters rating a high score on this index.

Equally important to note, many younger voters tend to withhold strong agreement on all 20 of the issues and values assessed, consistent with findings on other measures in the survey showing lower levels of attention and greater confusion about U.S. foreign policy among the youngest voters. More than 4 in 10 Generation Z/Millennial voters report no strong opinions at all on any of the 20 foreign policy questions, along with 36 percent of Generation X voters; in contrast, only one-fifth of Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters fall into the “no strong foreign policy worldview” category.

Social trust and Fox News effects on foreign policy views

The survey also included a three-part test of social trust, initially designed by the Pew Research Center, to help us examine whether, if at all, measures of interpersonal trust and perceptions of self-interest in other people influence foreign policy attitudes. The individual questions in the test, and their responses, include:

- “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” Thirty-eight percent of voters said most are trustworthy; 62 percent said you can’t be too careful.

- “Do you think most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would they try to be fair?” Forty-seven percent said most would try to be fair; 53 percent said most would take advantage.

- “Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful or that they are mostly just looking out for themselves?” Fifty-one percent said most of the time people try to be helpful; 49 percent said people mostly look out for themselves.

The three questions were then combined into an index with designations for high social trust, comprising 27 percent of the electorate; medium social trust, with 38 percent of the electorate; and low social trust, with 35 percent of the electorate, that allow us to examine the demographic composition of each group and to explore any potential differences on foreign policy views across the groups.

Social trust clearly increases with age and education levels, as Pew initially discovered in 2007. Baby Boomer/Silent Generation voters make up more than half of the high social trust group, with 52 percent—twice the share represented by either the Generation Z/Millennial or Generation X cohorts, with 25 percent and 23 percent, respectively. Likewise, college educated voters comprise more than half of the high social trust group, with 51 percent, while noncollege educated voters make up 69 percent of the low social trust category. In terms of the gender breakdown, men comprise a majority of the high social trust group with 53 percent, while women make up the majority of the low social trust group, with 54 percent.

Looking at Figure 16, social trust in turn corresponds with several important trends on foreign policy and national security issues. Voters in the high social trust category report higher levels of attention to foreign policy news and developments, higher levels of perceived personal impact and connections to others, and higher levels of agreement that U.S values are universal than do voters in the low social trust category. Voters with high social trust are also in much stronger agreement with ideas about U.S. leadership in the world and the need for international cooperation. Forty-eight percent of high social trust voters rate a high score on the global leadership index, described in the previous section, and 46 percent rate a high score on the multilateral cooperation index, compared with 33 percent and 28 percent of voters with low social trust, respectively. Conversely, voters with low social trust are more likely to rate a high score on the “America First” index, at 39 percent, than are voters with high social trust, at 27 percent.

Although these findings require more examination, it is interesting and important to see how views about interpersonal trust and self-interest help shape overall opinions about the United States’ role in the world. Given lower levels of social trust among the youngest generations, it remains to be seen if American voters will desire an even greater retreat from global engagement in the future, as Generation Z/Millennial voters come to make up a larger share of the electorate. Apathy may be more at work with these voters than outright opposition to robust engagement, but this area requires more research.

Turning to the impact of partisan media on foreign policy views, the study finds strong relationships between regular Fox News viewership—those who watch the cable network daily or weekly—and a range of foreign policy attitudes, particularly those related to “America First” nationalism. Some of this relationship between viewership and views is surely interactive, as Republicans and people who hold nationalist or pro-Trump views are more likely to gravitate toward Fox News coverage.

But the independent effect of Fox News on foreign policy views should be considered—37 percent of regular Fox News viewers in this survey self-identify as either Democrats or Independents, and 34 percent voted for President Barack Obama in the 2012 election. As a leading source of information for many of Trump’s most ardent backers, as well as others not aligned with the Republican Party, Fox News has become a virtual megaphone for much of Trump’s nationalist pitch and his desired support for increased military spending and cuts to domestic programs. Subsequently, this study finds that regular Fox News viewers of all backgrounds score much higher than those who never watch Fox News on both the military engagement and “America First” indices.

As Table 4 highlights, regular Fox News viewers are twice as likely as non-Fox viewers to rate a high score on the military engagement index—44 percent versus 22 percent—and nearly twice as likely to rate a high score on the “America First” index—50 percent versus 26 percent. The strongest interaction of Fox News with foreign policy views is on the issue of immigration: 71 percent of regular Fox News viewers strongly agree that “in order to protect our country, we must secure our borders and put strong limits on both legal and illegal immigration,” compared with only 46 percent of voters overall.

Looking at other media effects, we find that regular viewers of both MSNBC and CNN score much higher than voters overall—and than regular Fox News viewers in particular—on the multilateral cooperation index: 57 percent of regular MSNBC viewers and 51 percent of regular CNN viewers score high on this index, compared with 35 percent of voters overall and 28 percent of regular Fox News watchers.

Profiles of the major electorate groups based on foreign policy views

Given the massive amount of information in this survey, we tried to condense the results into more manageable categories of voters based on their responses to multiple questions across multiple aspects of the survey. Based on exploratory factor analysis, a statistical method that examines the underlying structure of large numbers of variables, we find that there are three independent dimensions to voters’ views related, first, to U.S. leadership and military engagement; second, to nationalism and anti-immigration concerns; and third, to diplomacy and domestic investment over military action and to cooperation with allies on key global issues. Building off of this factor analysis, we assigned scores to each survey respondent based on their answers to the questions with statistically valid correlations to these three independent factors, which, in turn, become three major voter segments described below.

This process produced three independent and quite interesting voter segments labeled as follows: “traditional internationalists,” comprising 18 percent of the electorate, “Trump nationalists,” comprising 33 percent of the electorate, and “global activists,” comprising 28 percent of the electorate. A fourth category of “foreign policy-disengaged” voters, 21 percent of the electorate, was created to fully break down the entire voting population. Descriptions of each voter segment, plus important demographic and partisan breakdowns for each segment, are described in the text boxes below.

Views of other countries

Although prior surveys have explored Americans’ opinions about other countries or regions, our qualitative phase suggested that voters hold some competing ideas about these relationships.5 In the survey, we therefore presented a range of countries and requested of respondents, “Please indicate whether you think this country or group of countries is mostly a friend of the United States, mostly an enemy of the United States, or mostly a competitor of the United States,” and directed them to pick the one label that best describes the country or region in their mind if more than one applies.

Examining Table 5, the list of countries or group of countries described as mostly a friend of the United States by majorities of American voters is topped by the United Kingdom at 81 percent, followed by France at 70 percent, Germany at 61 percent, Israel at 61 percent, the European Union at 56 percent, and Japan at 56 percent.