See also: Investments Along China’s Belt and Road Initiative by Ariella Viehe, Aarthi Gunasekaran, Vivian Wang, and Stefanie Merchant

China is increasingly flexing its economic muscle in order to assert itself as a responsible global power. The United States’ reaction has been generally skeptical—even negative. In March 2015, the United States at first privately and then publicly opposed China’s establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, or AIIB, even as 53 other countries joined as founding members. In July, dramatic falls in the Chinese currency market sparked renewed U.S. concern regarding China’s assertive role in international finance and its potentially destabilizing effects on global commerce, as well as its influence on the U.S. dollar’s dominance as a global currency.

While these developments raise questions within the United States and other developed countries, many developing countries eagerly welcome China’s investment. Chinese investments in Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe—provided under the new Belt and Road initiative—are responding to the regions’ need for investment and development. Such development is certainly a boon to China, as well as the United States. New rail, roads, and ports provide access to previously excluded regions, such as the energy-rich states of Central Asia, while new energy and communications infrastructure can accelerate productivity for local economies in South and Southeast Asia. Yet, for the economies of these developing countries and the United States’ own economic interests in the region, how—and if—China will undertake these development initiatives in a cooperative and sustainable manner is crucial to understand.

The Belt and Road initiative concept

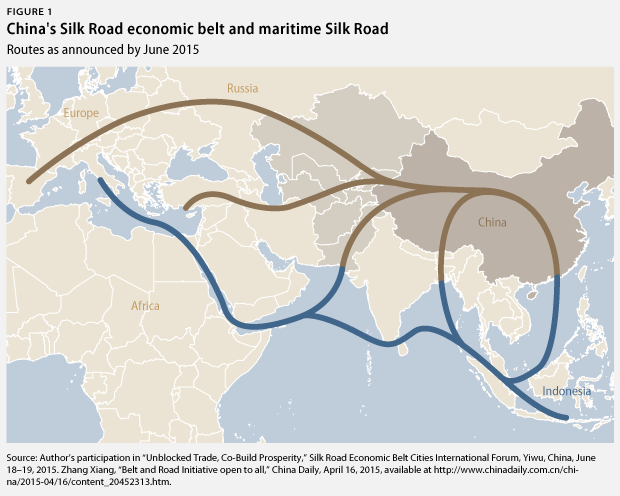

In September 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping formally announced the Silk Road Economic Belt in Kazakhstan and subsequently expanded the program to include the Maritime Silk Road in February 2014. Commonly referred to in English as the Belt and Road initiative, the program aims to unlock massive trade potential and bolster economic development to the so-called belt—the land route starting in western China that crosses through Central Asia to the Middle East—as well as to the so-called road: the maritime route around Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf, and the Horn of Africa.

Given its leading role in decades of global development, the United States should keep an eye on the Belt and Road initiative’s expansion but avoid instinctively reacting negatively to China’s global economic ambitions. The United States should instead assess specific projects in key regions and make smarter, nuanced assessments regarding China’s rising role in the world and its effect on the international system, as well as what it will mean for U.S. interests around Asia and beyond.

The Belt and Road initiative has become a defining strategy for economic outreach to China’s partners—a wide range of nations that include Spain, Indonesia, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, as well as others. The United States’ reaction has been fairly muted. In a March 2015 Washington, D.C., panel, Deputy Secretary of State Tony Blinken suggested that the Chinese effort was “consistent” with U.S. goals and could be “complimentary” with U.S. efforts but had few examples to offer.

The Belt and Road initiative in reality

Through open-source and field research, the Center for American Progress has tracked funded Belt and Road initiatives in order to see where and how these contracts and projects are developing—specifically focusing on which countries in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa are receiving heavy investment, as well as what types of projects are emerging. Current projects reflect China’s economic expertise, such as financing comparatively low-cost manufacturing or infrastructure initiatives, and China’s global economic needs, such as easier access to ports and new sources of energy. For example, President Xi’s state visits have consistently highlighted new projects under the Belt and Road initiative, including the Suez Canal in Egypt, energy production in Pakistan, and port development in Indonesia. Also, recent maps of the Belt and Road initiative have adopted existing trade corridors as additions, including the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor, and others.

Despite locking in more than 1,400 contracted projects and $7.06 billion worth of contracts with more than 60 countries, the Belt and Road initiative has faced political, social, and economic obstacles that are an inherent part of economic development and global partnerships. How China responds and adapts to these obstacles will remain important for U.S. interests across Belt and Road initiative countries.

Belt and Road initiative quick facts

• More than 60 countries have welcomed Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road investments.

• China has launched the $40 billion Silk Road Fund for Belt and Road initiative projects. Current projects are also funded by the Chinese Development Bank, the Agriculture Development Bank, and the Export-Import Bank of China.

• Belt and Road initiative projects accounted for more than 40 percent of China’s overseas construction projects in the first half of 2015, with returns to be realized over a period of 10 years or more.

• As of July 2015, the Belt and Road initiative has announced more than 1,400 contracted projects related to high-speed rail, electricity upgrades, port development and enhancements, as well as coal power plants.

• Chinese enterprises have signed $7.06 billion worth of contracts with more than 60 countries involved in the Belt and Road initiative—a year-on-year increase of 17 percent.

• China has specified five types of Belt and Road initiative projects: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and strengthening people-to-people bonds.

• China’s gross domestic product, or GDP, growth is expected to fall below 7 percent as early as 2015, making Silk Road connections more important for private-sector growth outside of China, as well as for excess manufacturing capacity such as building new markets overseas.

Four key takeaways

Current Belt and Road initiative projects are linked by their proximity and utility to diversify and insulate China’s trade access. The Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor will allow China to circumvent India and the Straits of Malacca, and as a result, it is critical in shortening Chinese trade routes. Israel is an inland corridor that keeps China immune from the effects of Egypt’s political instability on the Suez Canal. Indonesia’s ports and strategic maritime location is a critical pillar in Southeast Asian trade, while Europe is another destination market for Chinese goods and finance. Recently, China and Spain have heralded an agreement for rail transportation from western China’s Xinjiang province to Madrid, Spain. The rail line is expected to cut the transit time between the two destinations by more than half, taking approximately 21 days rather than 45 days through shipping routes. Similarly, new energy development in Pakistan and Central Asia seeks to diversify energy access as China observes the volatility in the Middle East. Furthermore, China has sought to vary its financial markets, seeking linkages with Germany’s Börse stock exchange in order to increase trading in renminbi and accelerate its use as a global currency.

The Belt and Road initiative pursues development projects that enhance the domestic economic viability of potential trade partners. For example, investments with Southeast Asian countries include large infrastructure projects—ports, energy plants, and urban housing—that meet the host countries’ development demands. The theme of integration and connectivity inherent to the Belt and Road initiative is in sync with other similar regional initiatives, such as the still-developing Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity. Through Chinese government-backed financial institutions and the $40 billion Silk Road Fund, Chinese loans offer financing beyond what partner governments or other international institutions are offering. Many of these countries welcome Belt and Road initiative investments—particularly in expensive infrastructure—but some countries, such as Ukraine, are already struggling to repay the extensive loans that are required to finance such projects.

The Belt and Road initiative is heavily invested in countries that have both a strong government relationship with China and hold popular support for Chinese investment. China’s bilateral relationships with partner countries have been key—both in ensuring political support for Chinese-led development, as well as in providing domestic security and engagement with villages and workers affected by Chinese projects. This is a nuanced departure from China’s traditional noninterference approach to development and business relationships with partner countries. China’s strong political connections on the government level have been useful for its economic activity in partner countries. For example, Pakistan has promised to provide domestic security forces for its $46 billion Chinese-led Belt and Road initiative projects. However, in other countries, China’s bilateral relationships have weakened at the local level. Construction of the Myitsone Dam in Myanmar is at a standstill due to local protests regarding the environmental and cultural effects of damming the river. Sri Lanka has also halted Chinese-funded projects because of development and political concerns. As the Myanmar Institute of Strategic and International Studies has noted:

[T]he Belt and Road Initiative was generally welcomed by many countries, but there were also countries that had concerns and apprehensions … [success] would greatly depend on the successful implementation of the project.

Such projects in the region have not appeared as official projects of the Belt and Road initiative.

Finally, as the above trends imply, while Chinese firms and government entities are pursuing Belt and Road initiative projects independently of one another, their respective tracks are both parallel and coordinated. CAP’s analysis of press reports notes that the commercial efforts—such as those in the Special Economic Zone for Myanmar—are largely motivated by how investments will help China’s economy. Other contracts, such as handshake agreements between two governments, are worked out between Chinese government entities—embassies and ministries—and partner governments and then handed off to Chinese companies to implement. With its overarching goals, the broad Belt and Road initiative has allowed the Chinese government and Chinese companies to work in relative tandem.

The Belt and Road initiative is fulfilling a global demand for investment and development that can connect millions of people and spur increased economic growth for both China and many other nations stuck in their development paths. Yet, as one Chinese interlocutor noted, “We rely too much on money to solve our problems.” As its experience in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and elsewhere indicates, China will need to grapple with the additional political, social, and economic considerations inherent to successful investment and development. With the international development community prioritizing sustainability, it is in the interest of China, the United States, and partner countries to ensure that the Belt and Road initiative continues to evolve and adapt in the coming months and years. Such adaptation can not only achieve important economic development—it can also ensure China does so sustainably and in a manner that does not undermine that very development.

Ariella Viehe is a CFR Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Aarthi Gunasekaran is a Research Assistant at the Center. Hanna Downing is a former intern at the Center.

The views expressed in this article by Ariella Viehe are her own and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of State or the U.S. Government.

This issue brief is supported by research trips taken by the authors to China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Myanmar.