The U.S. Department of Defense’s fiscal year 2015 budget request outlines a sound path to responsibly meet the risks and challenges of the current national security environment. The plan also proposes a number of smart, targeted reductions to defense spending that will maintain U.S. military capabilities and the All-Volunteer Force while helping return the country to a peacetime footing. Nonetheless, the Pentagon’s planning process indicates that it is still operating under the assumption that the near-record-high funding levels that characterized the decade after 9/11 will return—and if the U.S. Department of Defense, or DOD, can just weather this short-term budgetary storm, it can avoid adjusting its long-term plans to reflect existing fiscal realities.

Key points

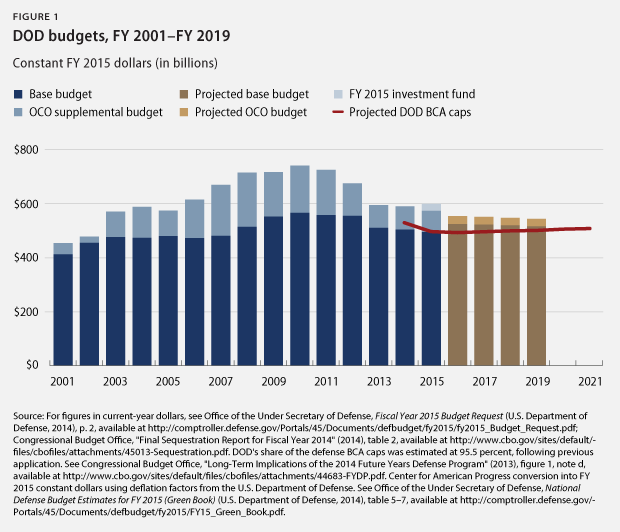

The U.S. Department of Defense is requesting $495.6 billion in authority for the base budget in FY 2015 in line with the Budget Control Act, or BCA, caps as revised by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. The department, however, envisions future base budgets that exceed the BCA caps from FY 2016 to FY 2019. Overall, the Pentagon is asking for $115 billion more than the BCA caps over the next five years in current dollars.

The request also includes an additional $26 billion in FY 2015 for the defense portion of President Barack Obama’s Opportunity, Growth and Security Initiative, or OGSI; the initiative is intended to fund readiness, investment, and installation spending not included in the base budget. If appropriated, however, this $26 billion would breach the BCA caps, triggering a sequester unless Congress revisits the caps.

The Pentagon’s FY 2015 request also includes a placeholder request of $79 billion in Overseas Contingency Operations, or OCO, funding. The department has said that it cannot provide a more accurate estimate of war-funding requirements until a bilateral security agreement is signed with Afghanistan, but experts believe it will total between $50 billion and $79 billion. OCO funding is effectively exempt from the BCA caps. In addition to future base budgets that exceed the BCA caps, DOD’s FY 2015 request includes placeholder OCO requests of $30 billion annually—in current dollars—for FY 2016 to FY 2019.

Congress also requested that DOD submit an unfunded priorities list that outlines programs it would like to fund that did not make the budget. These requests total about $36 billion. Again, any appropriations to this $36 billion list would be subject to the BCA caps and would trigger sequestration unless they were offset or the caps were revised, meaning that the unfunded priorities list is essentially a wish list for Congress to consider. The services’ unfunded priorities lists overlap with the defense portion of the OGSI list but request additional funding for aircraft and the Air National Guard.

DOD’s total budget request is therefore $601 billion: $496 billion for the base budget, $26 billion for the defense portion of the OGSI, and $79 billion for OCO. Including the portions of the congressionally requested unfunded priorities list that are distinct from the OGSI items would further increase the total request.

Understanding the Budget Control Act caps

The sequester, or BCA caps, are the product of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which put in place limits on discretionary spending. These caps are enforced by automatic cuts if appropriated funds exceed the year’s cap, a process known as a sequester. In FY 2013, the defense sequester was approximately $42.7 billion.

The BCA-mandated savings are split evenly between defense and non-defense spending. The defense category is comprised of the Office of Management and Budget’s Budget Function 50, which includes the U.S. Department of Defense, funding appropriated for military construction, and defense-related appropriations for the U.S. Department of Energy largely related to nuclear weapons and safety. The non-defense spending category comprises all other discretionary appropriations. In past years, DOD has accounted for approximately 96 percent of the BCA defense caps.

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, passed in December of that year, revised the BCA caps for fiscal years 2014 and 2015; analysts now refer to these “revised BCA caps” when discussing the spending limits. The Bipartisan Budget Act raised the FY 2014 cap for discretionary defense spending by about $22 billion for a revised cap of $520 billion; it raised the FY 2015 cap by about $9 billion for a revised cap of $521 billion. The caps for national defense discretionary spending extend through FY 2021, rising by approximately 2 percent annually to reach $590 billion in FY 2021.

The money that Congress appropriates for Overseas Contingency Operations funding raises the BCA caps by the same amount. OCO funding, in effect, is not subject to the BCA caps.

Under the BCA caps, therefore, the DOD base budget—its portion of the overall defense share—is capped at $496 billion in FY 2015, before rising steadily to about $554 billion in FY 2021. For context, the FY 2015 base budget cap of $496 billion for the Pentagon is higher in real terms than the base budget in FY 2005 in inflation-adjusted terms; it is $20 billion above the department’s total budget in FY 2002, including OCO funding.

But DOD’s base budget only adheres to the caps for one year—FY 2015—and the department’s Future Years Defense Program, or FYDP, calls for a cumulative $115 billion above the caps in base budget funding for FY 2015 through FY 2019 in current dollars. Adjusted for inflation, this is cumulatively about $111 billion above the caps.

Additionally, DOD’s total budget will be well above the BCA caps due to OCO funding. The Pentagon has requested $79 billion in OCO funding for FY 2015 and plans to request an additional $30 billion annually through FY 2019. Because OCO funding is not subject to the BCA caps, it has the effect of allowing for a substantially larger defense budget.

Understanding Overseas Contingency Operations

The Pentagon’s budget request includes placeholder Overseas Contingency Operations requests of $79 billion in FY 2015 and $30 billion annually from FY 2016 to FY 2019. While these are only estimates, it means that the department is anticipating spending an additional $199 billion in OCO funding—nominally for the war in Afghanistan—over the next five years, over and above the base budget.

As stated above, OCO funding is not subject to the Budget Control Act caps. As such, many budget analysts have raised concerns that additional OCO funding may allow the Pentagon to get around the caps. Indeed, OCO funding actually increased from FY 2013 to FY 2014 despite decreases in the number of deployed troops in Afghanistan. A number of experts have concluded that the U.S Department of Defense is using the OCO funding accounts to pay for expenditures unrelated to the war in Afghanistan, most recently by shifting $9.3 billion in operations and maintenance funding originally included in the base budget. Even consistent advocates for higher defense spending such as Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) have condemned this practice.

OCO and other supplemental funding for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have ranged between a low of $17 billion in FY 2002—$24 billion in FY 2015 dollars—and a peak of $187 billion dollars in FY 2008—$201 billion in FY 2015 dollars—before declining to a $79 billion request this year. At the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in FY 2007 and FY 2008, OCO funding made up approximately 30 percent of the total defense budget. The FY 2015 placeholder request of $79 billion for OCO is equivalent to 13 percent of DOD’s total budget request. In other words, DOD is roughly halfway toward preparing for future budgets with lower or nonexistent OCO funding, which will become likely as the mission in Afghanistan winds down. For now, DOD remains dependent on the OCO funds; the $79 billion OCO placeholder is nearly 1.5 times the reductions in spending required by the sequester under the original BCA caps.

The defense budget in context

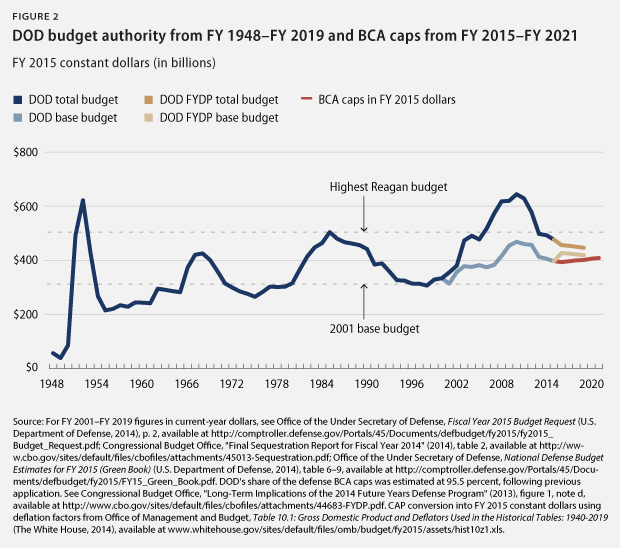

The United States continues to spend roughly three times more on defense than its nearest competitor and about as much as the next nine largest countries in the world combined, many of which are allies. This year’s base budget request of $496 billion is $15 billion more than the FY 2005 base budget request when adjusted for inflation. In FY 2005, the United States had 163,000 troops deployed to active war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Including the $79 billon Overseas Contingency Operations placeholder but excluding the $26 billion DOD share of the Opportunity, Growth and Security Initiative request, as well as the $36 billion unfunded priorities list requested by Congress, the department’s total budget request for FY 2015 is $575 billion. This is on par with total defense spending in FY 2005 in constant dollars, larger than the budget was at any point during the Vietnam War, and higher than all but two years of the defense budget during President Ronald Reagan’s military buildup.

The base budget remains far above pre-war levels: The request of $496 billion is $83 billion more than the FY 2001 base budget in real terms, meaning it is 20 percent higher than its baseline before the recent wars. If OCO funding is included, this year’s total request of $575 billion is $120 billion above the total FY 2001 pre-war budget, a 26 percent increase.

But defense has drawn down somewhat from the record highs at the end of the Bush administration and the beginning of the Obama administration. The total FY 2015 budget request is 22 percent lower than the Pentagon’s all-time budget highs of $716 billion in FY 2008, $718 billion in FY 2009, and $742 billion in FY 2010 in real terms during the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. On a year-to-year basis, the FY 2015 total budget request is $22 billion, or 3.7 percent, less than the enacted FY 2014 budget. Essentially, DOD is halfway through a postwar drawdown, if pre-war levels are used as a baseline.

While the FY 2015 budget request and the department’s plans for FY 2016 to FY 2019 represent a decrease in defense spending after the conclusion of the Iraq War and the drawdown in Afghanistan, the budget remains very high in historic terms. As stated above, the FY 2015 budget request—including OCO funding—is larger than the budget was at any point during the Vietnam War and higher than all but two years of the defense budget during the Reagan buildup. And despite the drawdowns in Iraq and Afghanistan, the $601 billion total defense budget request is still 39 percent larger than the Pentagon’s FY 2000 budget in real terms.

The FY 2015 base budget request

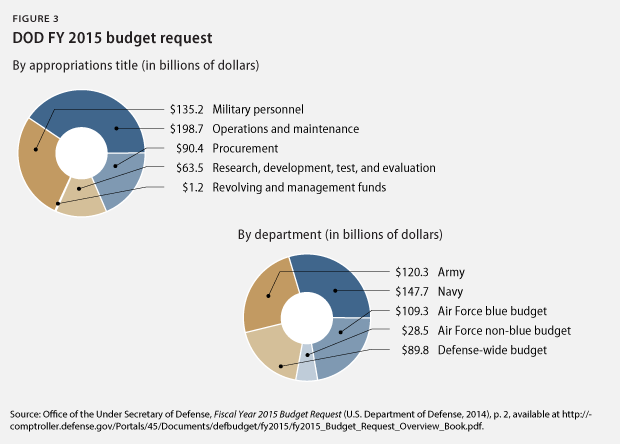

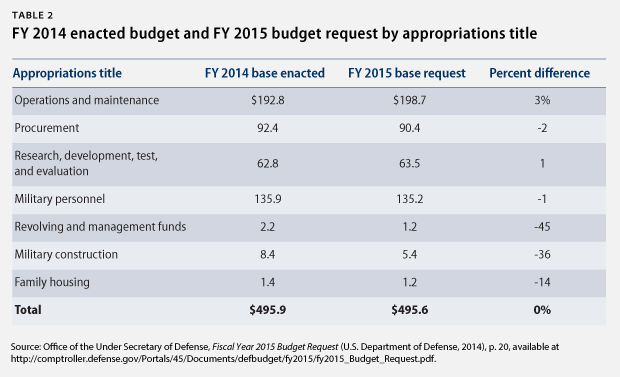

The fiscal year 2015 base budget request is $495.6 billion, $0.4 billion less than the FY 2014 enacted base budget of $496 billion, or a decline of 0.08 percent. It is about $15 billion dollars more than the FY 2005 base budget of $481 billion after adjusting for inflation.

With the exception of the small Revolving and Management Funds title, each appropriations title sees only minor fluctuations from the final FY 2014 enacted figures.

Smart choices in the FY 2015 defense budget

The FY 2015 defense budget request would put the U.S. Department of Defense on a path to responsibly meet the risks and challenges of the current national security environment in a fiscally responsible manner. As part of this plan, the request proposes a number of smart, targeted reductions to certain areas of defense spending to free up the funds needed for investments to maintain the United States’ technological and qualitative military advantages and the All-Volunteer Force. These smart choices focus on five areas:

- Reductions in ground forces following more than a decade of large-scale ground interventions that necessitated a large increase in the size of the force.

- Targeted investments in research, testing, and procurement needed to improve mobility, intelligence and surveillance, communications, and power-projection capability through air and sea power.

- Shifting of procurement funds away from programs unsuitable to contested operational environments, as well as the slowing of programs that face hurdles in development and testing.

- Provisions to slow the growth of military compensation costs.

- Efforts to reduce DOD’s overhead costs and get rid of excess infrastructure.

Maintaining a smaller, adaptable force

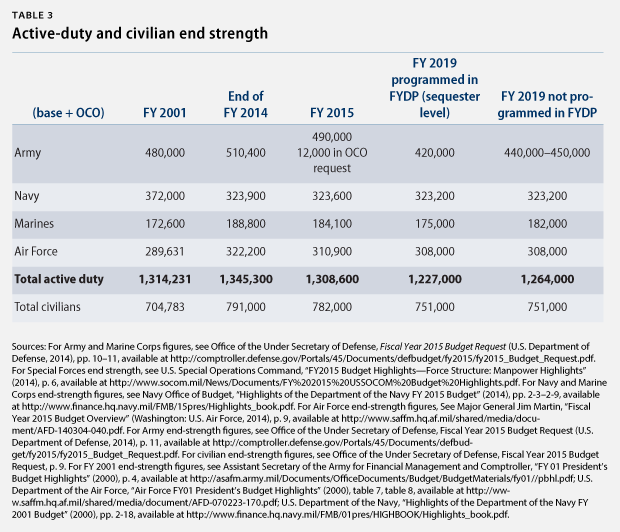

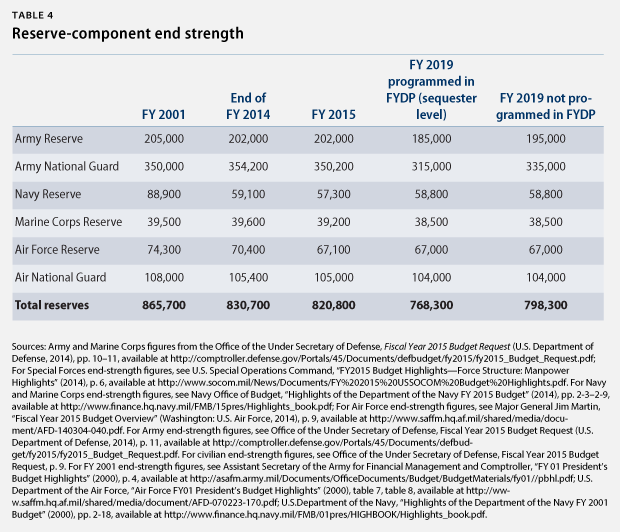

The U.S. Department of Defense has publicly stated its intention to reduce the size of the active-duty Army to between 440,000 and 450,000 troops and reduce the Marine Corps to 182,000 troops, acknowledging the shift away from large-scale stabilization operations. The plan calls for smaller, more-deployable ground forces, increasing Special Forces’ end-strength levels to 69,700. To hedge against the possibility of an unforeseen, large-scale ground contingency, the department has said it intends to maintain a robust Army National Guard and Reserve capability of 335,000 and 205,000 soldiers, respectively. These Guard and Reserve units have acquitted themselves excellently in Iraq and Afghanistan and will allow the country to surge ground forces if major, long-term contingencies arise.

But there are discrepancies in DOD’s stated end-strength goals and its budget planning. Despite public statements and briefings outlining an active-duty Army of between 440,000 and 450,000 troops and an active-duty Marine Corps of 182,000 troops, the department’s budget plan does not include funding to maintain these levels. In fact, its FY 2015 Future Years Defense Program, which extends through 2019, plans for lower end-strength levels of 420,000 active-duty Army troops and 175,000 active-duty Marines. Likewise, the Future Years Defense Program plans for an Army National Guard of 315,000 troops, rather than the publicly stated level of 335,000, and an Army Reserve of 185,000, rather than the publicly stated level of 195,000.

Essentially, DOD is planning for the worst and hoping for the best. It elected to set its budget to the amended Budget Control Act caps—which remain in force and represent current law—in the FY 2015 FYDP. This choice is prudent and should be applauded. The confusion stems from the Obama administration’s goal of securing more funding for defense from FY 2016 to FY 2019—the higher end-strength levels are basically aspirational. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and Pentagon Comptroller Robert F. Hale have told Congress that DOD will change its future plans and ensure higher end-strength levels if given the $115 billion above the BCA caps that it asked for in the FY 2015 FYDP. DOD has been unable to answer congressional questions about why the higher-force levels were not included in the 2015 FYDP despite the nominal inclusion of the extra $115 billion.

Focusing on modernization

The FY 2015 defense budget request includes $90.7 billion in procurement funding and $63.5 billion in funding for research, development, testing, and evaluation. In line with the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review and the 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance, the plan prioritizes procurement programs designed to enhance U.S. military mobility, intelligence and surveillance, communications and interoperability, and power projection.

In line with these priorities, airlift and refueling assets receive significant investments—both in FY 2015 and over the course of the Future Years Defense Program—to protect and enhance the military’s ability to move forces quickly and support remote deployments and disaster-relief efforts. Likewise, airborne early warning and control aircraft and long-range surveillance drones are prioritized, along with efforts to upgrade communications and networking equipment and insulate these systems from electronic and cyber threats.

The Pentagon’s procurement plan also calls for large investments in systems designed to improve the United States’ ability to project power around the globe and in contested environments. At sea, this power projection is bolstered by the purchase of two Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers per year through 2019, continued work on the nuclear-powered super-carrier USS John F. Kennedy, and funds to buy two Virginia-class submarines per year through 2019. To maintain airborne strike capabilities, the U.S. Department of Defense plans to continue the purchase of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, although the department will slow purchases in light of budget uncertainty and continuing challenges in the development and testing of the three variants of the fifth-generation stealth fighter. Finally, the plan begins to allocate funds for the development of a next-generation long-range strike bomber to maintain the Air Force’s global strike capabilities.

Major modernization investments include:

- $0.9 billion for the early stages of development of the next-generation Long-Range Strike Bomber

- $2.4 billion for 7 KC-46 tankers in FY 2015 and $16.5 billion for 69 tankers over the course of the FYDP to ensure a modern tanker fleet

- $1.4 billion for 16 C-130-J and 1 KC-130J tactical airlift aircraft in FY 2015

- $1 billion over the FYDP to develop a next-generation, fuel-efficient jet engine

- $775 million to remanufacture 25 Apache attack helicopters, $1 billion for 6 new and 26 remanufactured heavy-lift CH-47 Chinook helicopters, $0.4 billion for 55 Lakota light utility helicopters, and $1.4 billion for 79 Black Hawk utility helicopters

- $6.3 billion for 2 Virginia-class attack submarines in FY 2015 and $28 billion over the FYDP to acquire 2 more per year, for a total of 10 submarines through FY 2019

- $2.9 billion to buy 2 DDG-51 Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers in FY 2015 and $16 billion for a total of 10 ships through FY 2019

- $2.1 billion for the third year of construction on the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy

- $1.2 billion for 4 E-2D Advanced Hawkeye airborne early warning aircraft in FY 2015 and a total of 25 aircraft through FY 2019

- $2.4 billion for 8 P-8A Poseidon aircraft in 2015, as well as 56 planes through FY 2019

- $1 billion for 29 MH-60R Seahawk multimission helicopters

- $0.9 billion for 26 AH-1Z Viper/UH-1Y Venom Marine Corps helicopters

- $1.1 billion for RQ-4 Global Hawk/MQ-4C Triton high-altitude surveillance drones to replace the manned U-2 spy plane

- $5.1 billion for cyber operations

- $11.5 billion for science and technology programs

- $7.2 billion for space systems, including $1.4 billion for the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle, $1 billion for GPS satellites, $0.6 billion for military communications satellites, and $0.7 billion for infrared detection satellites

- $0.5 billion for the Tactical Networking Radio System and $0.9 billion for the Army’s Warfighter Information Network-Tactical, or WIN-T

- $6.8 billion for Ballistic Missile Defense System

These procurement decisions are, on the whole, smart and well suited to the current national security and budgetary environment. They will allow the U.S. military to deploy more quickly and project power in the face of anti-access and area-denial capabilities currently being developed by potential adversaries. Many of the choices reflect a welcome focus on versatile systems that can carry a wide range of payloads, which is in line with what Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert has described as the need to “move from ‘luxury-car’ platforms—with their built-in capabilities—toward dependable ‘trucks’ that can handle a changing payload selection.” The Navy’s decision to continue buying Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and curtail procurement of the expensive Zumwalt-class reflects this concept.

The Pentagon is also making investments that will help develop next-generation systems while maintaining expertise and human capital in the industrial base. The next-generation jet engine and the early stages of the next-generation long-range strike bomber fall into this category. Likewise, the Navy has begun to study the potential procurement of a small and lethal frigate in light of concerns about the survivability of the littoral combat ship, or LCS. Provided that requirements for these new systems remain reasonable and the focus is kept on payloads, versatility, and affordability, these could be promising programs.

Smart reductions and cuts

The proposed budget reduces, slows, or ends procurement of several platforms that are either ill-suited to the increasingly nonpermissive security environment or that have become unaffordable and are squeezing out more important investments. These steps include cutting the number of littoral combat ships that the Navy plans to buy, buying fewer of several more vulnerable drone classes, and terminating the Army Ground Combat Vehicle, or GCV, program.

The LCS has long been a source of controversy, attracting harsh criticism from analysts, watchdog groups, and members of Congress due to its cost and questions about its capabilities and survivability. Critics claim that the ship is slower than required, ill-suited for the long distances of the Pacific Ocean, and lacking the firepower necessary to engage enemy surface combatants of any size. The Government Accountability Office, or GAO, concluded last year that the program’s “cost and its anticipated capabilities … have degraded over time.” The assessment describes the LCS as “under-performing” and offering “little chance of survival in a combat scenario,” concluding that it is “not to be employed outside a benign, low-threat environment unless escorted.” For a program that has cost $12 billion over the past 10 years, this is wholly unacceptable.

Given these concerns, DOD decided to reduce its planned purchase to 32 ships, down from the original planned buy of 52, and consider alternate solutions, including frigates. The department should consider further reducing the size of the LCS buy—potentially by eliminating the less effective of the two entirely separate ship classes currently being developed—and move to find a more affordable and survivable small-surface combatant.

The Pentagon also elected to cancel the GCV program, saving $3.4 billion over the course of the FYDP and as much as $34 billion over the life of the program. The GCV was the successor to the problem-plagued and poorly managed Future Combat System, or FCS, which was cancelled in 2009 after about $14 billion in spending. In an April 2013 Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, report, Army officials concluded that increasing weight and size would limit the GCV’s utility in likely future combat scenarios, while CBO expressed concerns about the ambitious schedule, technological hurdles, and anticipated cost. The Pentagon also decided to forego expensive modernization of the Army’s ageing Kiowa helicopter. The Kiowa’s armed reconnaissance role can be effectively performed by existing unmanned systems at a lower cost, helping free up funds to modernize the Apache, Chinook, Blackhawk, and Lakota helicopters. The decision also streamlines the Army’s helicopter training, maintenance, and supply chain.

DOD elected to slow and slightly reduce procurement of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter in its FY 2015 request. The F-35 is the costliest weapons system in history—the GAO’s most recent cost estimate for operating and supporting the fleet is more than $1 trillion over its lifespan—and the largest and most controversial major acquisition program underway today. In an effort to save money and speed the development of the system, DOD has executed the program with a high level of concurrency, seeking to buy significant numbers of airframes while testing and development are still underway. While some level of concurrency is necessary in any program—airframes are needed for testing and development of other airframes—numerous studies by the GAO and other watchdogs have recommended slowing procurement to allow developmental challenges to be addressed. Unfortunately, all three variants of the aircraft have faced many such difficulties in development, with the carrier-based F-35C carrier variant and the Marine Corps’ F-35B short takeoff and vertical landing variants encountering particular challenges. The latest setback came this year, when Michael Gilmore, the Pentagon’s director of Operational Test and Evaluation, said that the delivery of combat-ready aircraft could be delayed by more than a year, due largely to software problems with all variants and structural issues with the Marine Corps and Navy variants.

DOD’s FY 2015 plan acknowledges these realities in part by slowing procurement of the Navy variant to two airframes per year for the next two years and slightly reducing the Air Force’s buy this year. The decision on the Navy variant essentially keeps the program at the level required to continue work developing the aircraft. While DOD is presenting this decision as a choice driven by budgetary circumstances—and while the decision will save money—it is also smart and long overdue. The delay should give the development teams and testers time to work through the existing problems and develop the software needed to operationalize the F-35. It will also ensure that the United States is not buying large numbers of airframes that are not ready and will need extensive, expensive upgrading and alterations later. The slight reduction in the Air Force’s buy to 26 airframes from the planned 30 is an acknowledgement of the software challenges that the program still faces and the lack of an existential threat requiring such rapid procurement.

Despite reducing the planned buy, the United States will still buy 34 F-35’s in FY 2015 and 343 aircraft over the Future Years Defense Program under the Pentagon’s plan at a cost of $8.3 billion this year and close to $50 billion over the next five years. The department could go further by examining the Marine Corps variant, which has encountered serious problems in development but has not been slowed down under the new plan. We have also previously argued that the Navy should not be forced to buy the F-35C—which some Navy leaders privately hold deep reservations about—and could instead continue procurement of the F-18 E/F/G variants at a much lower cost without sacrificing much in terms of capability.

Reducing procurement of unstealthy drones is also a prudent step. Due to years of procurement and use in Iraq and Afghanistan, the services have large fleets of unstealthy drones, such as the MQ-1B Predator and the MQ-1C Reaper, which have performed well in permissive environments. But with the operational tempo of drone strikes declining, the department is wise to focus future drone procurement on systems better suited to operate in contested airspace.

In summary, smart reductions in the FY 2015 budget request include:

- Reducing the number of LCSs that the DOD plans to buy to 32 ships and considering alternate solutions, including frigates.

- Terminating the GCV, which would save $3.4 billion.

- Foregoing expensive modernization of the Army’s aging Kiowa helicopters to save $12 billion over the FYDP.

- Slowing procurement of the Joint Strike Fighter F-35; purchasing 34 planes in FY 2015 at a cost of $8.3 billion, instead of 42 as planned; and planning to buy a total of 343 aircraft over the FYDP at a cost of close to $50 billion.

- Reducing funding for unstealthy drones such as the MQ-1B Predator, MQ-1C Reaper, and other drones ill-suited for contested airspace.

Slowing the growth of military compensation costs

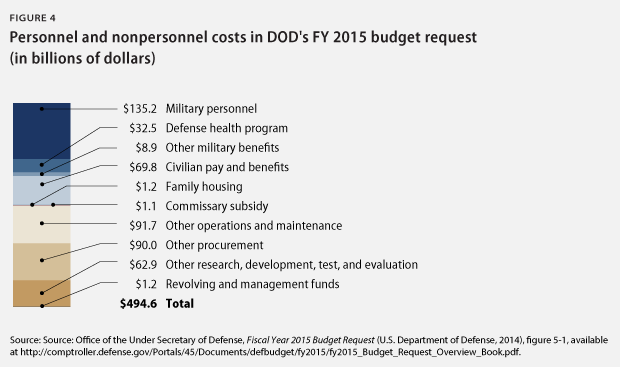

Service members’ pay and benefits currently make up more than one-third of DOD’s budget. Including civilian employees, DOD’s people account for roughly 50 percent of the FY 2015 budget request. Reforms are necessary to ensure that the services meet their responsibilities to our troops while investing in crucial modernization and readiness accounts to make sure that they have the equipment and training they need to safely execute their missions.

In addition to the military personnel appropriations, a significant portion of the Operation and Maintenance, or O&M, appropriations pays for personnel costs, including the Defense Health Program, the DOD Education Activity, and other benefits. In FY 2015, the request for the military personnel appropriations title is $135 billion, with an additional $47.6 billion and $70 billion—principally in the O&M request—for military benefits and civilian pay and benefits, respectively. Overall, the Pentagon’s compensation costs in the FY 2015 request amount to $246 billion, or about 50 percent of its total base budget.

DOD has proposed several appropriate and modest reforms to slow the growth of compensation costs. Incorporating these reforms, the military personnel title will be $144 billion by FY 2019; this reflects both slower growth in compensation costs and a reduction in total end-strength. These reforms include:

- Smaller pay increases of 1 percent in FY 2015 and FY 2016, 1.5 percent in FY 2017, and 2.8 percent in both FY 2018 and FY 2019. These steps would save $3.8 billion over the FYDP.

- Slower increases to the Basic Allowance for Housing, or BAH, to bring its coverage to 95 percent of housing and utility costs, down from the current 100 percent coverage but well above the 80 percent coverage of the 1990s. This adjustment would save $5 billion over the FYDP.

- Less-generous subsidies for military commissaries, which currently receive $1.4 billion annually to cover overhead and employee wages. This would save $3.9 billion over the FYDP.

- Simplifying the TRICARE system and incorporating slightly higher deductibles and co-pays, which have increased only slightly since the system was inaugurated in 1996. This would save $9.3 billion over the FYDP.

Reducing Pentagon overhead

The U.S. Department of Defense’s FY 2015 budget request asks Congress to authorize the creation of a new Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, or BRAC, to formulate a plan to reduce excess military infrastructure. The Pentagon itself estimates that it has roughly 20 percent excess infrastructure, or facilities that do not reflect current force structure and defense priorities. While the U.S. Government Accountability Office has noted problems with the department’s methods for estimating this excess infrastructure, both the GAO and the Pentagon agree that only a new round of BRAC can determine how many facilities are no longer needed and which facilities should be shuttered. While members of Congress have previously been reluctant to authorize a new BRAC to protect installations in their districts, the time has come to allow DOD to rationalize its infrastructure to reflect the new force structure. The proposed BRAC, planned for FY 2017, would initially cost $1.7 billion dollars but would save millions of dollars annually in perpetuity. As part of the FY 2015 request, the department also announced plans for a number of efficiency measures, including reducing headquarters staffing, greater contracting efficiencies, more effective use of resources, and savings due to slower growth of health care costs. Collectively, these savings are estimated to total $73.5 billion.

Budget problems ahead

While the fiscal year 2015 defense budget request complies with the amended Budget Control Act caps, the U.S. Department of Defense faces significant problems in adhering to the caps in the remaining years of the Future Years Defense Program from FY 2016 to FY 2019. These problems are partly of DOD’s own making as the Pentagon has repeatedly failed to plan to the BCA-cap levels even though they have been the law of the land for nearly three years. The department’s assumption that near-record-high funding levels will return has underpinned its attempts to weather what it views as a short-term budgetary storm rather than fundamentally reworking its long-term plans to reflect existing fiscal realities.

Indeed, as recently as April 15, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Frank Kendall publicly said that “the way we’ve been handling [the uncertainty] in the department is to act as if the uncertainty will go away.” This is imprudent and has contributed to the confused budget presented to Congress this year, which laid out a program that complied with the BCA caps for one year before exceeding them for the remainder of the five-year plan. To compound the confusion, defense officials have shown little transparency about what a five-year budget that fully adheres to the BCA caps would fund or cut. In addition, although the base budget request for FY 2015 meets the BCA levels, the 2015 total budget request also included two additional and overlapping requests that would each exceed the BCA caps—the Opportunity, Growth and Security Initiative and the unfunded priorities list.

For the remainder of the FYDP—from FY 2016 through FY 2019—the Pentagon’s budget plans would exceed the BCA caps by a total of $115 billion in current dollars, about $111 billion in inflation-adjusted terms. Defense officials have said that if DOD is required to comply with the BCA caps, it would have to reduce the force to sequester levels of ground forces end-strength and shipbuilding. This would mean 420,000 active-duty Army soldiers, 175,000 Marines, 185,000 Army Reservists, and 315,000 Army National Guard members—60,000 to 70,000 troops fewer than the non-sequester level. Defense leaders have also claimed that the sequester level of funding will force the early retirement of one aircraft carrier, bringing the fleet to 10. However, the FY 2019 BCA cap for DOD will be about $500 billion in FY 2015 dollars, essentially holding the Pentagon’s budget flat in real terms over the next five years. These are hardly the dramatic cuts some commentators have described.

Even including the extra $115 billion above the BCA caps, the Pentagon’s current budget request reflects the sequester level of ground forces end-strength and shipbuilding. This is reportedly due to a very late decision to add the extra $115 billion over the FYDP, leaving the extra funds to be applied to the more fungible readiness and modernization accounts. If the administration decides to count on receiving funding over the BCA caps, it would need to reprogram the defense budget for FY 2016 onward—if Congress does not raise the BCA caps. Since congressional leaders have shown no indication that they will raise the BCA caps for defense, DOD would be better served by acknowledging and planning for the reality of them. By budgeting to the BCA caps for FY 2016 through FY 2019, the Pentagon could avoid another budget-planning scramble in advance of the FY 2016 budget process.

Congressional reluctance to implement the cuts and reforms that DOD is requesting as part of the FY 2015 budget could compound the Pentagon’s budget woes. Congressional leaders have pronounced the proposed compensation reforms, the retirements of the A-10 Warthog and the U-2 spy plane, the delayed Ticonderoga-class cruiser modifications, the Army’s rotorcraft realignment, and end-strength reductions all “dead on arrival.” While these statements may be political posturing, any cuts or reforms Congress decides to overturn will have to be offset elsewhere in the budget, since the proposals are already written into DOD’s budget plans for FY 2016 to FY 2019. Congressional decisions to reject DOD plans will mean having to find other savings in the defense budget. The department has outlined savings totaling $39.5 billion over the next five years; if Congress rejects the proposed cuts or reforms detailed below, DOD will need to find equivalent savings over the five-year plan. Its major choices are:

- Slowing the rate of military pay raises—saving $3.8 billion

- Slowing the growth of housing allowances—saving $5 billion

- Reducing commissary subsidies—saving $3.9 billion

- Consolidating TRICARE—saving $9.3 billion

- Divesting the A-10 fleet—saving $3.7 billion

- Delaying modernization of the Ticonderoga-class cruisers—saving $4 billion

- Divesting the Kiowa helicopters—saving $12 billion

- Reducing headquarters staff—saving $5.3 billion

- Canceling the Ground Combat Vehicle—saving $3.4 billion

Ultimately, the root causes of the Pentagon’s budget problem are cost pressures from rising personnel and procurement costs, which are squeezing out other budget priorities. Using the department’s FY 2014 FYDP, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the real cost of the Pentagon’s plan would be $35 billion, or 7 percent, higher than the Pentagon’s own plans estimated in FY 2018 in constant FY 2014 dollars and well over the BCA caps. In an earlier report, CBO estimated that the costs of executing the Department’s 2013 FYDP would grow by 7 percent, or $88 billion in FY 2013 dollars, between FY 2013 and FY 2018; this is more than double the Pentagon’s projected cost growth of 4 percent, or $39 billion in FY 2013 dollars. CBO projected that 87 percent of the cost increase in the Pentagon’s plans would come from two major areas: major weapons systems costs, which would account for 41 percent of the increase, and personnel pay, benefits, and health care costs, which would make up 46 percent of the increase.

The Pentagon will be unable to maintain the country’s current national defense posture if these sources of cost growth are not addressed or if the overall defense budget is not significantly increased. Since a significant increase in defense spending is neither politically palatable nor desirable, Congress and the Pentagon must work together to pass and implement the reforms needed to put defense on a sustainable financial path. DOD has outlined a prudent course for FY 2015 and Congress should support it. For the FY 2016–2019 period, the department will have to make more hard choices to prioritize the investments needed to craft a force for the coming decades—one that is rapidly deployable, able to project power in contested environments, insulated from electronic and cyber attacks, and provided with the best intelligence and surveillance assets in the world.

Lawrence J. Korb is a Senior Fellow on the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Max Hoffman is a Policy Analyst at the Center. Katherine Blakeley is a Research Assistant at the Center.