Since the April 2012 military coup d’état that ended civilian rule in Guinea-Bissau, the international community has largely overlooked this small, Portuguese-speaking country in West Africa. In fact, Guinea-Bissau has quietly become what some experts have termed Africa’s first “narco-state,” as cocaine trafficking is now a widely accepted route to power and influence in Bissau-Guinean politics. This chaotic situation has allowed the military—Forças Armadas da Guiné-Bissau, or FAGB—to solidify its grip on political power, exploiting control of cocaine trafficking to play the role of kingmaker.

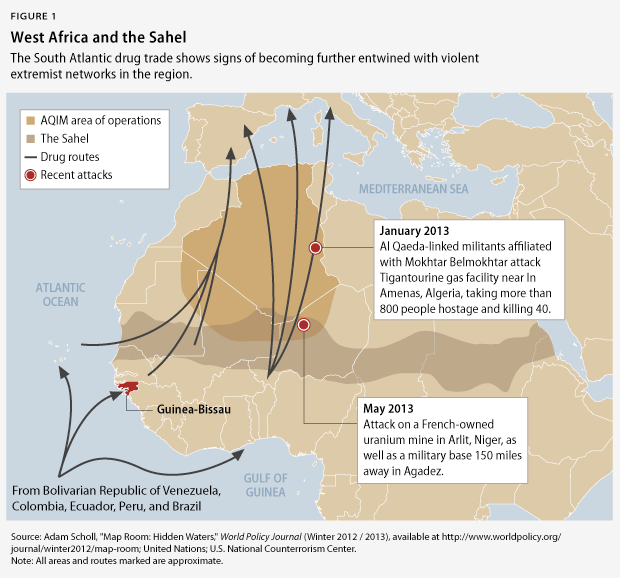

Guinea-Bissau’s governance gap has allowed the country to become an important hub of the global cocaine and arms trade, with destabilizing effects on U.S. and international interests in the region and beyond. What’s more, the burgeoning South Atlantic drug trade shows signs of becoming further entwined with violent extremist networks across West Africa and the Sahel—the belt of Africa between the Sahara Desert and the tropical savannahs—helping to finance groups and activities that undermine economic and political development.

This reality was demonstrated on April 18, 2013—a year after the coup—when it was revealed that key government officials had actively encouraged cocaine trafficking and arms trading within Guinea-Bissau. According to allegations by the U.S. Department of Justice:

Antonio Indjai [FAGB’s chief of staff] conspired to use his power and authority to be a middleman … for people he believed to be terrorists and narco-traffickers so they could store, and ultimately transport narcotics to the United States, and procure surface-to-air missiles and other military-grade hardware to be used against United States troops.

In May of this year, the United Nations reported that Indjai had conspired with individuals who he believed to be members of the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or FARC—a rebel group that the U.S. Department of State officially labels a “foreign terrorist organization” for its decades-long insurgency in Colombia. Over the preceding year Indjai had agreed to supply FARC with military-grade weapons for use against American-backed anti-narcotics programs in the Andes in exchange for a share of the profits from the Colombian group’s lucrative cocaine trade. Indjai and other Bissau-Guinean military officials also guaranteed safe passage through Guinea- Bissau for cocaine shipments en route to consumers in Europe and North America.

Unknown to Indjai, his would-be Colombian partners were actually undercover members of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, or DEA, who were sent to disrupt the emergent Latin American-West African cocaine trade. On April 4, after months of preparations, this special task force of DEA agents, disguised as FARC members, made several high-profile arrests of Bissau-Guinean military officials in international waters near Cape Verde.

These dramatic developments in Guinea-Bissau shed light on the spread of the cocaine trade across the Atlantic and illustrate how this trend threatens security efforts across two continents. The growth of this transatlantic cocaine trade has corroded governmental structures in fragile West African states already hampered by years of internal conflict and economic stagnation. This, in turn, undermines international efforts to restore constitutional order and build more transparent and representative democratic structures. Indjai’s attempt to establish drug and weapons links with FARC was also indicative of deepening connections between the illicit South Atlantic drug trade and wider networks of violent extremist groups and criminal gangs.

The range of these illicit nonstate actors is wide and varied in West Africa and across the Sahel, ranging from petty criminals and small-scale traffickers to kidnappers and violent extremists. As Vanda Felbab-Brown and James J. F. Forest pointed out in a Brookings Institution article, terrorist or extremist networks often form cooperative relationships with these wider criminal networks, depending upon them for financing and logistical support. For the international community, cooperation with Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, would be of greatest concern.

Many believe that AQIM is already playing a prominent role in the West African cocaine trade, levying taxes and protection charges on narcotics smuggled across the Sahara from coastal West Africa to Europe. The group’s co-founder, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who split with AQIM and then founded the Signers in Blood Battalion—a terrorist group active in Mali, Niger, and Algeria—even earned the nickname “le narco-Islamiste” for his involvement in regional cocaine trafficking. Moreover, the West Africa Commission on Drugs, or WACD, recently labeled the Gao region of northeastern Mali, where Belmokhtar and AQIM have been active, “a drug trafficking hub in West Africa.” In 2009 Malian officials found an abandoned Boeing 727—which was believed to have carried 5 to 10 tons of cocaine from Venezuela—in the desert near Tarkint, northeast of Gao. With an estimated 18 tons of cocaine—down from a 2007 peak of 47 tons—worth $1.25 billion passing through West Africa annually on the way to Europe, the trade presents a huge source of funding for the full range of illicit actors from Guinea-Bissau to Mali.

There is also evidence that AQIM has used this narcotics trade to help bankroll violent extremist activities. For one, Belmokhtar’s drug-financed Signers in Blood Battalion terrorized northern Mali during the Islamist takeover of the region in 2012. Elements of AQIM were also responsible for the January 13 attack on an Algerian oil facility that left dozens of western hostages dead. French troops reclaiming insurgent-controlled areas of Mali in 2013 uncovered huge caches of weapons stockpiled by AQIM-linked fighters in northern Mali and the Gao region, evidence of their well-financed operation.

Overall, Algerian intelligence officials estimate that AQIM earned more than $100 million from drug trafficking and kidnapping from 2003 to 2010, helping finance their militant operations. Taken together, a picture emerges of deep connections between cocaine trafficking and insurgent activities across West Africa, the Sahel, and the Sahara. To effectively curb terrorist activities in West and North Africa, the international community must target their sources of funding—largely the cocaine trade—which in turn requires a crackdown on the main ports of entry in Guinea-Bissau.

Addressing the narcotics trade in West Africa is complicated by its extensive links to undergoverned, peripheral regions in Latin America. As noted in the 2012 World Drug Report by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, or UNODC, the cocaine trade is supported by coca cultivation that is centered in isolated regions of Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. As depicted in “Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict in the Amazon and the Andes,” a recent report from the Center for American Progress, cocaine is processed in makeshift factories in rugged areas of the Andes and the Amazon before being transported to illicit markets in Brazil and the Southern Cone of South America. Cocaine is then frequently transported across the Atlantic from Brazil to Guinea-Bissau, a trade aided by linguistic affinity between the two Portuguese-speaking countries. From this waypoint on the West African coast, the drugs are then smuggled across the Sahara along well-established migratory routes and into Europe via Portugal or Spain.

The United Nations has sought to focus efforts on counteracting cocaine trafficking within the mandate of the U.N. Integrated Peace-Building Office in Guinea-Bissau, or UNIOGBIS, which is charged with strengthening “national capacity in order to maintain constitutional order, public security and full respect for the rule of law.” The UNODC and Interpol have helped Guinea-Bissau establish a Transnational Crime Unit to counter drug trafficking, but funding and political will for the efforts are both lacking, particularly in the wake of the coup.

Moreover, Guinea-Bissau has insufficient air and maritime surveillance assets to control its coastline, as well as insufficient drug-treatment facilities to treat the growing problem of indigenous consumption, as traffickers pay functionaries in product. But high-level corruption in the Bissau-Guinean military—the most likely partner in tackling narcotrafficking, as it is the only security structure present in Guinea-Bissau today— complicates international responses to the problem. As Indjai’s case demonstrates, elements within the FAGB are more than willing to work with extremist organizations that are hostile toward the United States and its allies when it proves lucrative. Given these connections and the paucity of surveillance assets, the United States should embrace UNIOGBIS and view an end to cocaine trafficking in Guinea-Bissau as central to its national-security interests in West Africa and beyond.

Given the lack of a reliable enforcement partner, however, the South Atlantic drug trade requires solutions that go beyond counternarcotics eradication or interdiction. Both Guinea-Bissau and the peripheral cocaine-producing regions of the Andes face deep economic stagnation, and few viable economic alternatives exist for impoverished rural communities in either region. Guinea-Bissau has languished in extreme poverty since its independence from Portugal in 1974 and was recently ranked 176th out of 184 countries in terms of health, education, and income indicators by the U.N. Development Programme’s 2013 Human Development Report. The drug trade therefore represents a lucrative option for many of the country’s poor residents, and poverty leaves them vulnerable to exploitation by well-financed crime syndicates. The United Nations reported on this vulnerability in 2006, indicating that “Guinea-Bissau’s gross domestic product (GDP) of $304 million equaled the wholesale value of six tons of cocaine in Europe.”

The profitability of cocaine trafficking and the lack of viable economic alternatives continue to attract Bissau-Guineans into the trade. As outlined in CAP’s aforementioned report, a similar situation exists in the peripheral areas of Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil, where the minimal state presence allows illicit economies to flourish. U.S.-backed anti-narcotics programs, however, focus almost solely on Colombia, where the vast majority of cocaine destined for the U.S. market is produced, and these dispositions have not adjusted to the spread of coca production into poor and indigenous communities in nearby regions.

The economic reality in Guinea-Bissau means that the international community must pair interdiction and eradication efforts with alternative development strategies to de-incentivize the production and trafficking of narcotics in peripheral areas of Latin America and in Guinea-Bissau. A June 2012 statement from Yury Fedotov, executive director of the UNODC, underlined this point. Fedotov outlined to the U.N. General Assembly that, “At present, only around one quarter of all farmers involved in illicit drug crop cultivation worldwide have access to development assistance. If we are to offer new opportunities and genuine alternatives, this needs to change.”

In Latin America the United States and Brazil should step up to this challenge and cooperate with governments to reinvest in peripheral regions of the Andes and the Amazon. Peruvian President Ollanta Humala, for example, expressed in a June 2013 speech at the Center for American Progress his administration’s desire to reinvigorate a U.S.-Peru partnership to expand economic opportunities in the peripheral Andean and Amazonian zones of his country, which have lagged behind Peru’s Pacific coastline in terms of development. The United States should reciprocate this show of goodwill by increasing and adjusting funding to USAID in Peru; in fiscal year 2012 the agency spent $26.4 million on counternarcotics programs and just $8.6 million on economic development in the country. The counternarcotics programs are valuable, helping authorities intercept drug traffickers associated with the Shining Path terrorist group—a Peruvian Maoist insurgency now deeply entangled in the cocaine trade—eradicate coca crops, and improve controls at ports and airports, but the Obama administration should also consider diverting more funds toward partnerships aimed at fostering sustainable development in the peripheral regions of Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia. Yet the United States cannot and should not tackle this problem alone; Brazil, in particular, must shoulder its share of the burden. Brazil is the world’s sixth-largest economy, has moved millions of its citizens out of poverty, is a crucial transit country, and has a huge domestic cocaine-consumption problem; it is now the second-largest consumer of cocaine and possibly the largest consumer of crack. These equities and capabilities demand greater involvement from Latin America’s regional leader.

In tandem with eradication and economic-development efforts at the Latin American points of origin, the United States and the international community should expand efforts to provide economic alternatives to cocaine trafficking in Guinea-Bissau. Guinea- Bissau, however, is no longer a direct recipient of U.S. aid, as economic assistance was cut off after the country’s 2012 coup. Given the legal restraints imposed on direct aid by the military coup, the United States should consider substantially increasing its support for UNIOGBIS, which maintains a major presence in the country, works to expand economic development, and oversees the political transition. Likewise, as in Latin America, Brazil can and should do more in West Africa. Brazil has pursued investment opportunities in the region—trade with Africa has increased from $4.2 billion to $27.6 billion in the last decade—and enjoys cultural and linguistic ties, and with these connections come responsibilities.

In spite of being the international community’s primary means to address the situation in Guinea-Bissau, UNIOGBIS recently reported that a lack of funding continues to undermine its ability to fulfill its mandate. The UNODC was even forced to downsize its office and activities in Guinea-Bissau in January 2013 due to the low funding. This dearth of funds should be unacceptable to the United States, Brazil, and the European Union—the destination for much of the cocaine transiting through West Africa.

The international community must also strengthen and incentivize existing regional initiatives to combat drug trafficking in the region, such as the Operational Plan on Illicit Drug Trafficking, which is coordinated by the Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, and is currently struggling with implementation and funding. Given the importance of a democratically elected government partner to development and security endeavors, ECOWAS should continue to work closely with relevant regional and subregional partners—including the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, and the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries— to oversee the peaceful transition to civilian rule in Guinea-Bissau through free, democratic, and transparent elections, which are currently planned for November 24. Implementation of the Defence and Security Sector Reform Program—to end impunity from prosecution for military officials, fully subordinate the armed forces to civilian rule, sort out conflicting areas of jurisdiction, and improve training—in accordance with the recommendations of the ECOWAS Committee of Chiefs of Defence Staff will be an important step toward this goal, helping improve security ahead of the national elections. Consistent with the recommendations of the African Union High-Level Consultation—designed to ensure adherence to the political road map and craft assistance packages for a newly elected government—the international community should also prepare options to support Guinea-Bissau politically and economically after its election, namely through a Governance and Economic Management Assistance Program.

Conclusion

The United States and the international community should view the creation of viable economic alternatives in Latin America and Guinea-Bissau as part of a sustainable solution to the proliferation of transatlantic cocaine trafficking. This trade has well-known social and health impacts in the United States, Latin America, Africa, and Europe, perpetuates economic underdevelopment in the producing and transit areas, and contributes to the strength of violent extremist groups on two continents. De-incentivizing coca farmers and cocaine traffickers through the creation of alternative economic opportunities can help the international community counter cocaine production, manufacturing, and sales.

By forging new partnerships with national governments and international organizations, the United States can ensure that its foreign assistance is used explicitly for the purpose of promoting economic development for the least privileged in the Andean and Amazonian regions of South America and at-risk regions of West Africa. Brazil should also help lead the efforts to foster alternative development in Guinea-Bissau and promote governmental stability, transparency, and accountability in Guinea-Bissau and the wider region.

West Africa continues to face a complex security crisis that demands a progressive and sustainable international response. The effects of economic and political insecurity across the region have grown more acute due to population growth, large-scale migration, and the burgeoning effects of climate change. In Guinea-Bissau, economic stagnation and a lack of viable economic alternatives have permitted narcotics traffickers to gain a foothold, undermining international efforts to promote political stability in the country. The emergent threat posed by the trafficking of cocaine, if left unaddressed, can further empower corrupt and potentially dangerous groups in West Africa and the Sahel that benefit from its profits.

The international community must therefore look not only to Guinea-Bissau but also to cocaine’s point of origin in peripheral regions of Latin America to sustainably address the problem. Indeed, thinking of the South Atlantic as a coherent geopolitical space for legal and illicit trade will improve our conceptual understanding of these new connections. The United States and the wider international community must resolve to partner with relevant national and regional representative bodies in the Western Hemisphere and West Africa to promote viable economic alternatives that de-incentivize coca cultivators and traffickers in both regions. The international community must also resolve to support the Guinea-Bissau government through its democratic transition, as the government’s current resource gap hinders the country’s ability to carry out the economic and political reforms that are necessary to effectively combat cocaine trafficking and promote sustainable economic growth during this critical phase.

Max Hoffman is a Research Associate at the Center for American Progress. Conor Lane is a researcher and Fulbright participant in Colombia.