*Author’s note, May 23, 2013: This report has been updated to reflect the new anti-foreign law bill that recently passed the North Carolina House.

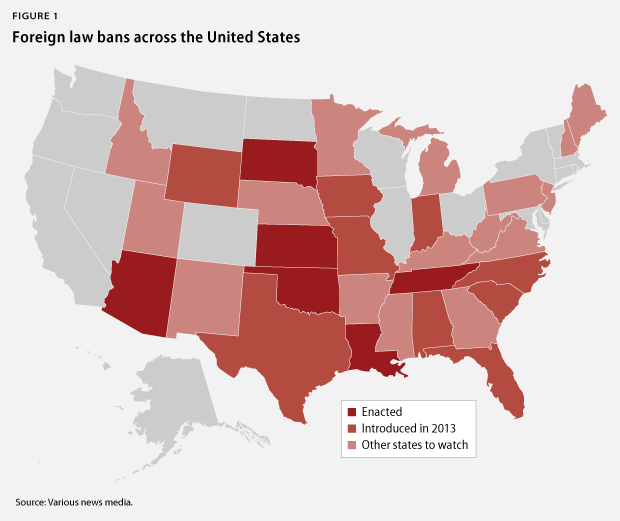

Over the past two years, a number of state legislatures have moved to ban the use of foreign or international law in legal disputes. As of the date of this report, lawmakers in 32 states have introduced and debated these types of bills. Foreign law bans have already been enacted in Oklahoma, Kansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arizona, while a related ban on the enforcement of “any religious code” has been enacted in South Dakota. Most recently, intensive campaigning by the Anti-Defamation League and religious freedom groups resulted in the defeat of a proposed foreign law ban in Florida. But at least six states are poised to pass similar measures in 2013 and 2014: Missouri, North Carolina, Texas, Alabama, South Carolina, and Iowa. Table 1 below illustrates the anti-foreign law movement across the country.

Although packaged as an effort to protect American values and democracy, the bans spring from a movement whose goal is the demonization of the Islamic faith. Beyond that, however, many foreign law bans are so broadly phrased as to cast doubt on the validity of a whole host of personal and business arrangements. Their enactment could result in years of litigation as state courts struggle to construe what these laws actually mean and how they interact with well-established legal doctrines. The legal uncertainties created by foreign law bans are the reason why a range of business and corporate interests as well as representatives of faith communities have mobilized against them. The American Bar Association, the country’s largest and most respected association of legal professionals, has also passed a resolution opposing the bans.

The most vociferous proponents of foreign law bans are a small network of activists who cast Muslim norms and culture, which they collectively and inaccurately labeled as Sharia law, as one of the greatest threats to American freedom since the Cold War. Ground zero for this effort was Oklahoma, and the lessons learned there provided a template for anti-Sharia efforts in other states. On Election Day 2010 Oklahoma voters overwhelmingly approved the Save Our State referendum, a ballot initiative that banned the use of Sharia in the state’s courts. While the Oklahoma measure was immediately challenged in court, and ultimately struck down as unconstitutionally discriminatory toward American Muslims, its proponents launched a nationwide movement to recast anti-Sharia measures as bans on foreign and international law. This involved removing specific references to Islam in order to help the measures pass legal muster and successfully tapping into deep-rooted suspicions about the influence of foreign laws over the American legal system. While the intent of foreign law bans is clear, proponents of these bans hope that the foreign law veneer will save the measures from being invalidated on constitutional grounds.

Most foreign law bans are crafted so that they seem to track the rules normally followed by courts when considering whether to apply foreign law. State courts consider drawing upon foreign law in situations ranging from contract disputes where the parties have selected the law of another nation as controlling, to cases where the validity of a marriage or custody arrangement concluded in another country are questioned. And state courts routinely apply foreign law provided it does not violate U.S. public policy. State courts, for example, will not recognize polygamous marriages, which are permitted in some Muslim countries, and most of them will not recognize marriages between same-sex couples, which are permitted in many European countries. While cases involving foreign law occasionally impinge upon American public policy concerns, most are quite uncontroversial. A typical case involving foreign law—described by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in a recent speech—would be one where the Court, for example, was called on to decide whether a corporation organized in the British Virgin Islands was a citizen or subject of a foreign state. The answer to the question depended on English law, and so the Court naturally looked to that body of law, said Justice Scalia.

The very premise of foreign law bans, however, is that law that comes from outside the United States is something to be feared. The bans depart sufficiently from current practice and jeopardize well-established rules regulating the application of foreign law in American courts. Several of the bans suggest that the use of foreign law is prohibited not only when the law at issue in a particular case is at variance with constitutional values, but also when the legal system of the country from which the law emerges is itself not in conformity with these values. That is to say laws from countries that do not protect rights in the same way that the United States does should be prohibited in U.S. courts. Kansas, for example, prohibits state courts from relying on foreign laws from any system that does not grant the same measure of rights provided under the U.S. and Kansas constitutions. The anti-foreign law bill that was recently signed into law in Oklahoma, as well as bills under consideration in Missouri and Iowa, are similar in scope. By essentially engaging state courts in wholesale evaluations of foreign legal systems, these bans open up the type of broad inquiry that is inimical to the case-by-case approach typically applied by American courts.

Through a detailed examination of the anti-Sharia movement and a look at how U.S. courts have traditionally approached foreign and religious law, this report shows that the foreign law bans are both anti-Muslim in intent and throw into question the status of a range of contractual arrangements involving foreign and religious law. The report begins by explaining how the anti-Sharia movement evolved into an anti-foreign law campaign in order to avoid the patently unconstitutional practice of explicitly targeting Muslims.

It next explains the role of foreign and international law in American courts and the difference between the two. The international law to which the United States subscribes—for example, treaties ratified by the Senate—is part of the law of the land by virtue of the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. Foreign law, on the other hand, is the domestic law of other countries and is used by American courts only where its application does not violate public policy. This section explains that while the use of foreign sources in constitutional interpretation is hotly contested, the consideration of foreign law in everyday disputes—such as those involving contracts—is largely uncontroversial and that courts have long used carefully calibrated tools to ensure that application of foreign laws does not violate U.S. policy.

We then turn to the specifics of the foreign law bans and demonstrate that some bans are inconsistent with the practice of U.S. courts and that all bans create uncertainty about how non-U.S. legal sources will be treated. The foreign law bans also raise serious questions under separation of powers principles, as well as the Full Faith and Credit and Contract clauses of the Constitution. The report next details the possible disruptive consequences of foreign law bans, particularly for American families and businesses, and then uncovers the true purpose of foreign law bans. Simply put, it is to target Muslims. Based on this context, we argue that the bans are vulnerable to challenge under the First Amendment and several state constitutions as unduly burdening the free exercise of religion.

The report concludes by recommending that state legislatures considering such bills should reject them, and those that have passed foreign law bans should repeal them. The bans set out to cure an illusory problem but could create a myriad of unintended real ones. These bans, moreover, send a message that a state is unreceptive to foreign businesses and minority groups, particularly Muslims. And, as this report details, these bans sow confusion about a variety of personal and business arrangements. The issues raised by foreign law bans may lead to decades of litigation as state courts examine their consequences and struggle to interpret them in ways that avoid constitutional concerns and discrimination against all minority faiths.

Fazia Patel is the co-director of the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program. Matthew Duss is a Policy Analyst at American Progress. Amos Toh serves as a legal fellow at the Brennan Center.