This column is part of a series of commentaries from scholars of Turkey reflecting on polling data provided by the Center for American Progress. The poll’s findings are summarized here; further analysis with reference to the focus groups is available here; and you can find further commentaries from a range of experts here.

In Turkey today, CAP’s nationwide polling shows, citizens’ political views largely define their understanding of reality and the world around them, rather than vice versa. The parameters of many Turks’ worldviews are shaped by membership in political identity groups familiar to observers of Turkish politics, such as “religious conservative” or “Kemalist.” Membership in these political identity groups is not interest-based or functional. Instead, it is attributed to supposedly old or inherent identity characteristics.

Overwhelmingly, the dominant identity group is Turkish nationalist. While the dominance of this political identity is not new, the degree to which it has overwhelmed previous divides between religiosity and secularism is noteworthy: Turkish nationalism is now the sole reference point for most Turks. The attribution of political positions to inherent, long-standing identity characteristics—rather than a particular political interest—substantially limits room for political maneuver or realignment for both voters and leaders. As a result of these broader trends, in part, the only real “swing votes” are between nationalist alternatives—the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). These parties are the likely beneficiaries of any voter movement and will compete for nationalist votes. This, in turn, means that anti-Western and anti-Kurdish policies and rhetoric—the cornerstones of modern Turkish nationalism—are likely to be durable features of Turkish politics in the near future. This does not bode well for Turkey’s place in the Western architecture.

Political worldviews shape voters’ perceptions

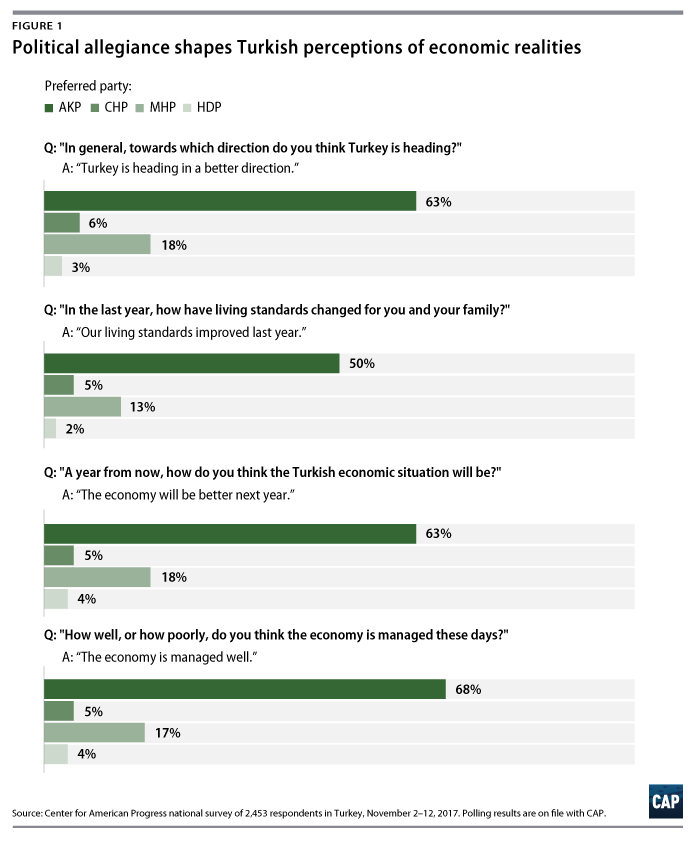

In a sign of Turkey’s extremely ideological and polarized society, political worldviews and positioning shape voters’ perceptions of economic and political affairs. This trend can be seen in poll respondents’ evaluation of their country’s overall course, the government’s management of the economy, their own economic situation, and their expectations regarding their own material well-being.

Political ideology clearly shapes voters’ perceptions. AKP voters differ dramatically in their assessment of the political and economic situations compared with voters of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Indeed, this political affiliation can verge on blind faith—roughly 18 percent of AKP supporters say the economy is managed effectively despite reporting that their own economic situation has worsened. Further evidence of the highly partisan atmosphere in Turkey lies in the fact that income and age have little effect on people’s response to these questions—partisan orientation was the only meaningful indicator shaping voters’ perceptions of external reality.

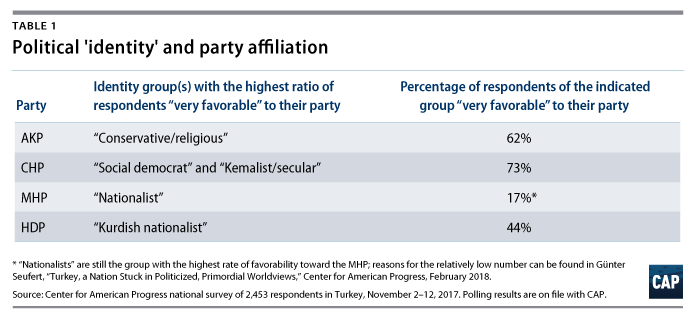

In Turkey, political orientation closely follows politicized conceptions of primordial attachment—affiliations that purport to constitute some sense of genuine or inherent belonging. These kinds of political identities are the main uniting adhesive for each party’s constituency. Neither ethnicity—be it Turkish, Kurdish, or Arab—nor income or education works as a meaningful societal base for political parties. Likewise, functional memberships—those acquired by one’s own decision, action, or performance—define Turks’ political orientation only to a very limited degree. For example, most Turks do not identify as being part of the working class, and similar functional political identities do not shape most people’s political views. Quite to the contrary, workers’ unions of different ideological camps compete with one another, as do conservative and secular women’s rights organizations or business groups. Table 2 shows the identity groups that the polling identified as the main supporters of single political parties.

Parties that try to establish their social base through identifications such as working-class consciousness or bourgeois attitudes struggle in today’s Turkey—as do parties built around specific political concerns or interest groups, such as individual freedoms or the environment. Thus, while in Germany the Green party grew out of interest groups and specific political concerns, such a movement would not resonate in present-day Turkish society. For example, ideological cleavages between religious conservatives and secularists, as well as between Kurdish and Turkish nationalists, prevented the nationwide demonstrations triggered by the attempted redevelopment of Istanbul’s Gezi Park in 2013 from giving birth to issue-based environmental or civil rights movements of any political significance.

What does it mean to be a Turk?

A large majority of Turkish citizens perceive the nation as homogeneous in ethnic (Turkish language) and religious (Muslim) terms. To be a true member of the nation, one also has to share conservative mores, or family values, and identify strongly with the nation state—embodied, for many, by the military. For those remaining outside this clearly defined in-group, life can be difficult. Therefore, the rhetoric of the current government—intended to differentiate between “true” members of the nation, steadfastly committed to Turkishness, Islam, and the state, and to denigrate all others as not belonging to the nation—falls on fertile ground.

Asked how important it is for them “to be a Turk,” only 11 percent of the respondents regarded this national identity as “not too important” or “not important at all.” The fact that a great portion of this 11 percent is made up by the almost completely Kurdish electorate of the HDP underlines the central role that national identity plays for the self-understanding of the average Turk. Regional, occupational, or class- or gender-based identities are, by comparison, much less significant.

The well-known division of Turkish society between the modernist and secular elite, on the one hand, and the conservative lower and lower middle class, on the other, still informs perceptions, rhetoric, and political developments. Today, however, Turkish nationalism has become the overarching distinction, and, without taking reference to Turkish nationalism, neither political Islam nor secularism provides a legitimate base for opposition.

These realities can be seen in the responses to the question “What does it mean to be a Turk?” Offered a number of possible attitudes and orientations and asked to indicate how significant these attitudes are for their understanding of what it means to be a Turk, respondents particularly favored four approaches. More than 65 percent pointed to “speaking Turkish,” “being Muslim,” “holding conservative familial values,” and “supporting the Turkish military” as being very important to them—these answers exceeded all other given options. When one includes respondents who held these orientations as “somewhat important” for them, scores reach 90 percent and more. Respondents accorded much less significance to other alternatives such as “holding a Turkish passport,” “being tolerant of different religious and ethnic groups,” “supporting democratic values,” or “being born in Turkey.” In other words, indicators of loyalty tied to supposedly inherent identity were more powerful than indicators of civic membership or political ideology.

This is in some respects a new phenomenon—ethnic Turkishness and respect for the military have not always cohabited so easily with conservative family values and religious devotion. Quite to the contrary, since the founding of the republic in 1923, political struggle in Turkey often showed traces of a culture war pitting these two forces in opposition to one another. The secularist elite—with the military at its center—propagated Turkishness as an alternative to religious belonging, while religious conservatives drew support from the lower classes and strove to keep conservative values and Islamic identity at the heart of the new nation. During the 1950s and 1960s, the right-wing conservative Democratic Party (DP), later followed by the Justice Party (AP), opposed the secular, modernizing CHP. In the 1970s, the conservative camp diversified and gave birth to both an explicit Islamic religious-conservative party tradition—the predecessors of the AKP—and an extremist Turkish party, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).* It was only then that ethnic definitions of Turkishness found a popular base among religious-conservative segments of the population, at least in the institutional form of a political party.

These two versions of nationalism have since been in competition. The MHP tradition underlined ethnic Turkishness, progress, and Europeanization while relegating religious feelings to the back seat. The AKP tradition focused on Muslim identity as well as on conservative social mores and worked for the resurrection of an imagined Islamic civilization. In the 2000s, the AKP saw its advocacy for democracy as part of a struggle to free Turkey’s conservative Muslim population from the oppressive rule of the secularist elite that had kept devout Muslims from political and economic power. In the 2010s, the AKP has likewise sought to grant cultural rights to Turkey’s Kurdish population, using the common Muslim tradition of Turks and Kurds as a reference point to eschew older, exclusionary notions of Turkishness.

The politicization of identity groups limits political repositioning

One effect of this politicization of identity groups—groups laying claim to allegedly deep-rooted historical traditions—is to limit substantially the space for political repositioning and changes of party allegiance among Turkish voters. This makes it very unlikely that Turkey will see changes in voting behavior on a scale that would shift the balance of power between the existing parties.

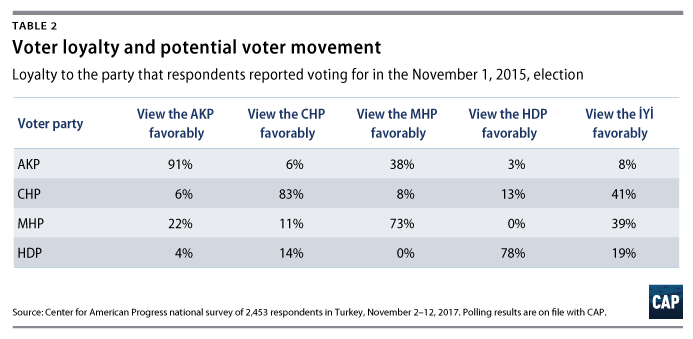

But how many swing votes are there in Turkey today, and in which direction could they move? Table 3 shows voter loyalty to the party voted for in the last election, casting light on how many voters could imagine casting a vote for another party. This loyalty is established by the percentage who still regard the party they previously voted for in a “very favorable” or “somewhat favorable” light in CAP’s poll. The results show that very few voters would consider voting for other parties, indicating the parties’ deep ideological divisions.

The AKP turns out to have the highest voter loyalty—91 percent of those who voted for the AKP in November 2015 are ready to stick with the party, compared with 83 percent for the CHP, 73 percent for the MHP, and 78 percent for the HDP.

Among the established Turkish parties, the largest swing-vote potential exists between the AKP and the MHP, to the advantage of latter. Only limited voter exchange seems possible between the CHP and the MHP, mostly benefiting the CHP. Possible voter movement between the AKP and the HDP is extremely small, and there is virtually no swing-vote potential between the HDP and the MHP.

The newly formed İYİ Party, or Good Party, founded by former MHP member Meral Akşener as a protest party against MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli’s alliance with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AKP, is something of an outlier. Although the İYİ Party appears insignificant in terms of political power, its high ratio of potential voter movement from the CHP and the MHP shows that there is a place for a party that opposes Erdoğan’s single rule, the AKP-driven erosion of secularism, and the possibility of granting more rights to the Kurds. However, the İYİ Party attracts most of its votes from the CHP and only a small portion from the AKP, meaning that major change is still unlikely. Even if the İYİ passes the 10 percent threshold for entering Parliament—which today looks unlikely, given the CAP polling results—it may do little to change the power relations between the pro-Erdoğan and the anti-Erdoğan blocs in Parliament. The low ratios of AKP voters that would consider supporting the CHP or the HDP likewise point to the opposition’s inability to extend its voter base.

Therefore, there is no need for the ruling party to change its policy toward the Kurds for electoral reasons. Aside from the MHP, which is dealing with a newly established competitor—the İYİ—coming from its own nationalist tradition, no established party risks losing as many voters as the pro-Kurdish HDP. The main reason for this is undoubtedly the efforts of Erdoğan and the AKP, as well as of Bahçeli and the MHP, to associate the HDP with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), as well as the inability of the HDP to distance itself convincingly from the PKK’s violence. The PKK has not managed to convince the electorate that the Turkish government bears the blame for the failure of its peace negotiations with the Turkish state from 2013 to 2015. The ensuing insurgency was a military disaster and ended with the destruction of many Kurdish towns. It remains to be seen if the Turkish offensive into Kurdish-controlled Afrin in northern Syria will lead to a new wave of transborder Kurdish activism. If so, the HDP may benefit politically.

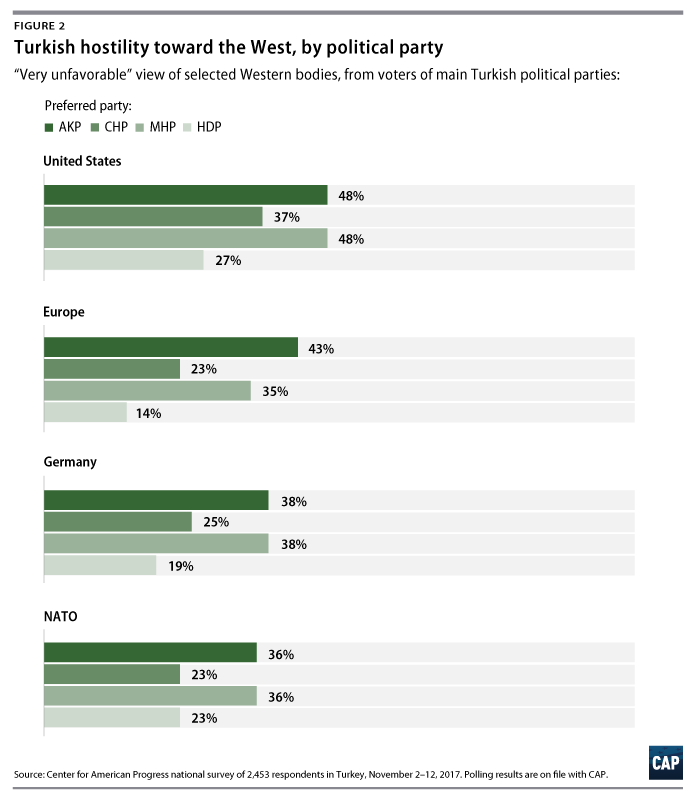

In short, Turkish politics is defined by the balance of power on the Turkish right—the AKP, the MHP, and the İYİ. Each of these conservative-religious and nationalist camps share anti-Western orientations. Indeed, anti-Westernism is today the main common ground between these groups and provides the most meaningful framework for nationalist orientations. The following table shows only the “very unfavorable” assessments of Western states and institutions—or radical rejection. The rates for moderate rejection are much higher.

In sum, CAP’s polling results do not bode well for the future of Turkey’s democracy or the country’s relations with the West. Domestically, ideological struggle completely overshadows and even distorts efforts to deal with economic and social issues and matters such as education, the environment and the judiciary. Political parties build their constituencies along the lines of politicized identities that mutually reinforce one another. The AKP has given up on its earlier efforts to bring the conservative electorate along the path of democratization, rule of law, cultural pluralism, and European accession. Turkish society does, however, share deep suspicion toward the West and its intentions toward Turkey. The United States is regarded as a threat, and Europe has lost its former significance as both an economic and a normative model. Neither Turkey nor Europe seems ready to complete the ongoing political transformation of Turkey.

Günter Seufert is a senior fellow with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin, where he focuses on political developments in Turkey and Europe.

* For more information, see Nuray Mert, “The Political History of Centre Right Parties: Discourses on Islam.” In Stefanos Yerasimos, Günter Seufert, and Karin Vorhoff, eds., Civil Society in the Grip of Nationalism: Studies on Political Culture in Contemporary Turkey (Istanbul: Ergon, 2000), pp. 49–97.