This article has been updated.

As the United States considers various responses to Russia’s military occupation in Ukraine and annexation of the Crimea, including ways to sanction Russia and support Ukraine, reform of the International Monetary Fund, or IMF, has emerged as part of a possible response. In choosing to drop a sensible IMF provision from legislation signed into law last week in response to Russia’s actions, Congress missed an important opportunity to ratify these needed reforms. But there is still time to act.

Why does the IMF matter?

The International Monetary Fund is a U.S.-led international institution founded just after World War II to promote international economic cooperation, foster financial stability, facilitate trade, reduce poverty, and promote sustainable economic growth.

The IMF has 188 member nations, which contribute to the organization and receive corresponding voting shares. The United States is the largest contributor to the IMF and the only country with unilateral veto power over IMF decisions. One role of the IMF is to provide loans to countries struggling to finance their international payments, such as imports or external debt, as they work to restore conditions for sound and stable growth. These loans are less risky and provide a more effective way of lending to countries in need because the risk is spread across all members. The United States has never lost money lending to the IMF.

Part of the IMF’s mission is to help struggling nations—such as Ukraine—weather economic turmoil and political upheaval. Helping to strengthen these economies is not only good for loan recipients; a strong global economy is of course good for America as well. Stronger economies are able to purchase more American goods, invest more in the United States, and prevent instability that can threaten growth, living standards, and our national security.

As a distinguished bipartisan group of former Cabinet members have stated, in the late 1990s, the IMF “helped restore growth to Asian economies and create robust export markets for U.S. businesses, which supports American jobs.” When the Global Recession hit in 2008, the IMF assumed a central leadership role in mitigating its worst effects. It is an efficient force multiplier, bringing the U.S. taxpayer greater impact for less cost; every dollar financed by the United States is matched by four or more dollars from the other members of the IMF. Without the IMF, the global effects of the Great Recession would have been far more severe, and the United States would have needed to take on a much greater burden to manage the crisis.

Reforms would make the IMF more effective

Although the IMF responded admirably to the global recession, it became clear that reforms are sorely needed to modernize the institution. Governance of the IMF is outdated, with outsized voting shares allocated to small European economies such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands, while minimal votes are allocated for large emerging market economies such as China, Brazil, and India.

When countries get more votes, their financial obligations increase too. Countries such as China, Brazil, and India are willing to take on more financial responsibility in international institutions, and the United States should actively encourage this burden sharing. As emerging markets continue to grow in size and influence, they can and should take on increased roles and responsibilities commensurate with their economic power. This strengthens the international system and the ability of the United States to engage constructively with rising powers.

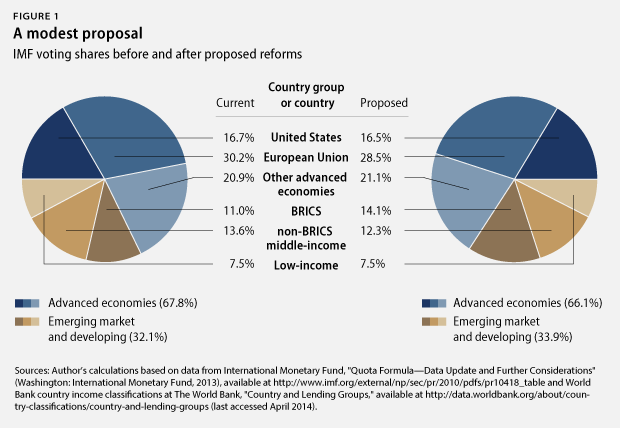

The proposed reforms build upon a series of reforms from the George W. Bush administration to align IMF resources and governance with changes in the global economy. These reforms would increase the voting power—called quotas in the IMF—of developing and emerging market countries and reduce European voting power and representation. At the same time, financial commitments and potential borrowing limits would change to correspond with the changes in voting shares. This would boost the IMF’s overall lending capacity.

The reforms would not increase U.S. financial commitments to the IMF. Current commitments are valued at about $170 billion, and that amount would not change, although the composition of the commitments would. The reforms would take $63 billion in available funds from our existing contribution to the IMF’s supplemental New Arrangements to Borrow and shift it to its core source of funding, improving the IMF’s flexibility and crisis-response capabilities. The Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, Congress’ official budget scorekeeper, estimates that shifting the $63 billion that the United States has already committed comes with a technical price tag of $239 million in new appropriations over the next 11 years. But the CBO estimates that shifting the funds from the New Arrangements to Borrow, or NAB, account would save $693 million over the same time frame—making this change an incredibly cost efficient way to boost IMF lending capacity and improve IMF governance.*

A chance for U.S. leadership

The proposed reforms leave U.S. influence in the institution undiminished: U.S. voting shares will change from 16.7 percent to 16.5 percent, preserving the highest number of voting shares among IMF member countries, as well as a longstanding U.S. veto over institutional changes.

More importantly, delaying reform weakens American credibility. The reforms were agreed upon internationally in 2010, including by the United States, and all other major economies have subsequently endorsed them. Currently, 144 countries have already ratified the reforms, including major U.S. allies—such as the United Kingdom, France, Korea, and Japan. Together, these nations represent more than 76 percent of the voting shares in the IMF. To enter into force, however, the reforms require approval of 85 percent of IMF membership. Because the United States holds 16.7 percent of the vote on the IMF Board, the rest of the world is waiting for Congress to approve these reforms. There is growing concern internationally that the United States lacks the ability and willingness to assume leadership of the modern global financial system.

The crisis in Ukraine

The crisis in Ukraine—and the need for a response from the United States and countries around the world—illustrates why IMF reforms are needed. Ukraine faces imminent economic collapse and a possible default on its debts. Its government has pledged to undertake serious reforms to stabilize its economy. Over the next several years, Ukraine will need help from the international community to reform its economy and stimulate growth.

The IMF will assume leadership in this task, and countries will look to the United States to play a major role in building consensus for the financial and political support that Ukraine needs desperately. Yet when the IMF and the G20 finance ministers meet this week in Washington, the United States will instead be on the defensive, explaining why it has failed to follow through on its pledge to ratify reforms already ratified in 144 other capitals. The United States’ reluctance to give emerging economies a seat at the table in existing international institutions impedes our ability to build political consensus and isolate Russia.

Congress should seize the opportunity for IMF reform

As the United States continues to advocate for a strong, international response to Russia’s military occupation and annexation of Crimea, IMF reforms should be considered as a part of that package. IMF reforms are important in and of themselves. But they also bolster a unified global response to help Ukraine counter political and military pressure from Russia and avoid economic collapse.

Ukraine is only one example of why IMF reforms matter. The reforms are a sensible and low-cost way to improve the effectiveness and influence of the United States on the global stage, maintain our veto power over IMF decisions, improve the distribution of financial burdens in international institutions, and bolster the ability to respond to global economic crises—all without increasing the cost to taxpayers.

Congress still has an opportunity to strengthen America’s standing on the global stage through IMF reform. It should take it.

Molly Elgin-Cossart is a Senior Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress.

*Correction, April 10, 2014: This article incorrectly stated the budget period for new appropriations. The correct number is 11 years. This article was updated to better describe the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates.