This issue brief is a product of CAP’s National Advisory Council on Eliminating the Black-White Wealth Gap.

Across the United States, small businesses are a significant source of employment and provide a variety of goods and services. For those who are fortunate enough to own a small business, they can also offer a pathway to wealth building and prosperity. Unfortunately, the ownership, profitability, and even presence of small businesses are grounded in differences in capital finance and unevenly distributed by race—especially when comparing Black and white communities.

While Black Americans make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they own less than 2 percent of small businesses with employees.1 By contrast, white Americans make up 60 percent of the U.S. population but own 82 percent of small employer firms.2 If financial capital were more evenly distributed and Black Americans enjoyed the same business ownership and success rates as their white counterparts, there would be approximately 860,000 additional Black-owned firms employing more than 10 million people.3

Small business disparities are caused by stark and persistent inequities in wealth and access to capital.4 While the federal government has largely perpetuated rather than mitigated these challenges, it nonetheless has an important role to play in creating a more equitable business environment.

A future presidential administration could meaningfully reduce small business disparities by revamping a long-neglected agency housed within the U.S. Department of Commerce: the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA). As the only federal agency created specifically to foster the establishment and growth of minority-owned businesses in the United States, the MBDA has a 50-year record of working in and for communities of color. While the MBDA’s effectiveness is currently limited by narrow authority and meager funding, its unique history and structure would allow a future administration that is dedicated to addressing racial inequality to expand the agency’s activities without new authorizing legislation. Under the current congressional appropriations, the president need only include language in his annual budget proposal asking for a significant increase in funding, which then could be used to:

- Initiate an economic equity grant program that would fund municipal projects that foster wealth creation, opportunity, and minority business development in Black communities.

- Launch a minority-serving institution (MSI) business center initiative within the MBDA, located in historically Black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, and other MSIs, that would provide substantial grants to operate business incubators and accelerators at every MSI in the country. These business centers would provide startup capital, technical and legal assistance, and other support for current students and community members interested in starting or expanding their own businesses.

- Create an office of research and evaluation charged with studying barriers to wealth and business development in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color and providing other MBDA offices and initiatives with technical assistance. Research activities would include conducting pilot and demonstration projects grounded with capital finance based on new and proven program concepts, such as baby bonds or debt-free college, to evaluate their effect on racial disparities in business development.

- Allow the MBDA to lend low-cost, government-backed capital to licensed minority business investment companies to invest in brown- and Black-owned businesses.

- Establish an office of advocacy and intergovernmental affairs to score the effects of proposed legislation and regulations on barriers to minority-owned small business creation and success; advance the economic concerns of Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color in front of various government bodies; and coordinate interagency efforts to support minority-owned businesses.

The effectiveness of these and other similar programs will ultimately depend on the amount and sustainability of federal funding. However, if crafted the right way—and if well-funded—revamping and reimagining the MBDA could help meaningfully reduce the racial wealth gap and increase the creation and success of Black-owned businesses over the coming years.

This issue brief provides an overview of the relationship between wealth, access to capital, and the Black-white business ownership gap; background on the MBDA; and a blueprint for reimagining and revamping the MBDA without the need of new authorizing legislation.

The business ownership gap is fueled by racial disparities in wealth and access to capital

The United States is home to inseparable racial disparities in wealth, access to capital, and business ownership. Wealth and capital are a prerequisite rather than just a product of entrepreneurship, and Black Americans have been systematically prevented from accumulating wealth and accessing capital for centuries. Despite this reality, lawmakers have consistently suggested that entrepreneurship seminars, technical assistance, and tax breaks for wealthy investors are all that are needed to produce wealth and opportunity in Black communities. It is more than clear that the United States cannot hope to close the business ownership gap without first addressing racial disparities in wealth and access to capital.

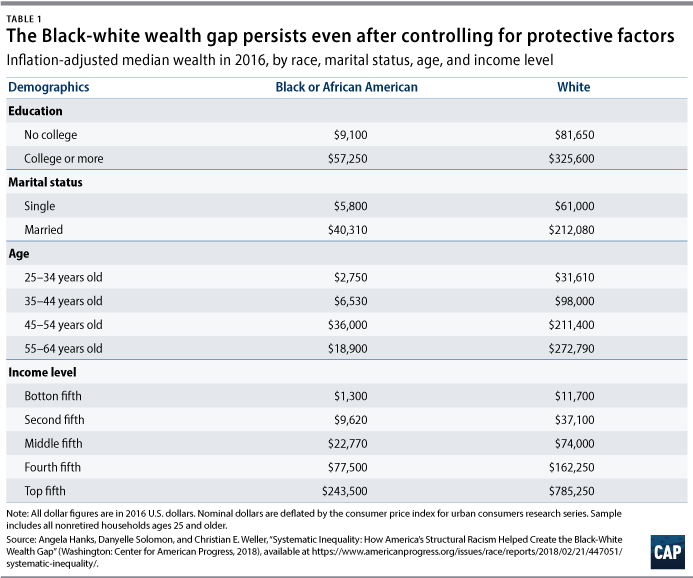

Starting, expanding, and sustaining a business almost always requires existing wealth. In fact, a business owner’s personal or family savings is the most commonly relied-upon source of startup capital.5 However, the typical Black household has just one-tenth of the wealth of their white counterparts—$17,600 compared with $171,000.6 (see Table 1) Without wealth, would-be Black entrepreneurs can neither invest directly in their companies nor secure collateralized business loans. Perhaps as a result, Black-owned firms are seven times less likely than white-owned firms to obtain business loans in their founding year.7 Even when Black-owned businesses do obtain loans, they are frequently much smaller in amount than those obtained by their white counterparts. The average Black-owned firm obtains just $35,205 in total startup capital during its first year compared with $106,720 for the average white-owned firm.8 While the Small Business Administration (SBA) is charged with helping all “Americans start, build, and grow businesses,” its efforts have fallen woefully short in Black communities.9 Black Americans make up approximately 13 percent of the U.S. population but receive just 3 percent of SBA loans.10 If these programs were equitably administered, Black firms would have received an additional $2.5 billion in loans in fiscal year 2019.11 Wealth disparities, combined with persistent racial discrimination in the credit system and neglect from federal agencies, play a critical role in maintaining the business ownership gap.12

Efforts to foster, promote, and develop Black-owned businesses must go beyond a focus on household wealth and access to capital for Black entrepreneurs. Without wealth at the community level, existing Black-owned businesses may also struggle to maintain their financial footing during sustained economic downturns. During such periods, regular clients and customers may have fewer resources to support their local veterinarian, mechanic, or contractor, even if their services are needed. For example, just 49 percent of Black-owned firms that existed in 2002 survived through the Great Recession compared with 60 percent of white-owned firms.13 The coronavirus crisis is producing similar results: The number of active Black-owned businesses plummeted by 41 percent between February 2020 and April 2020.14 Wealth at the community level is essential for the long-term success of Black-owned small businesses.

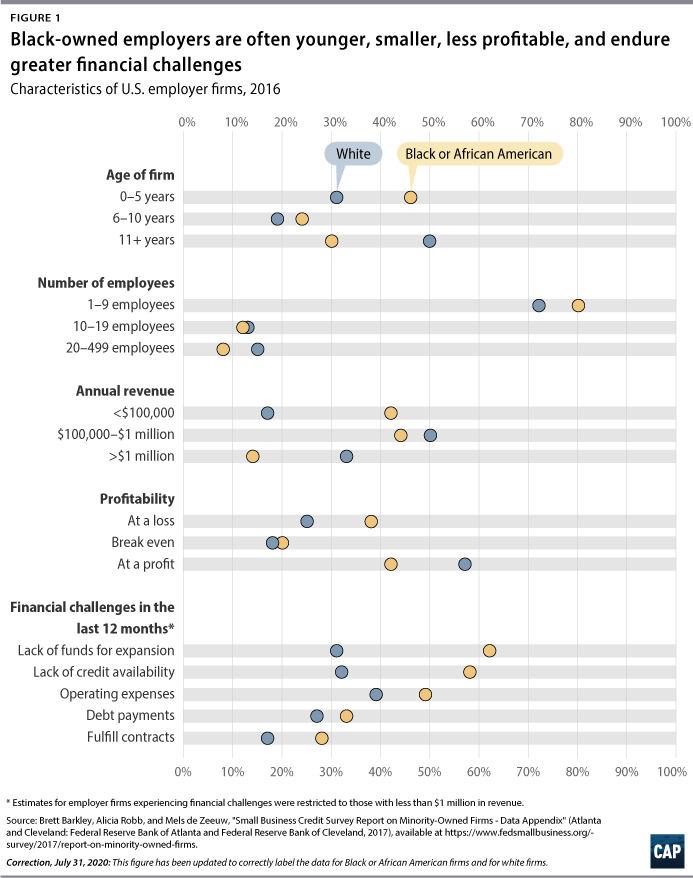

The current state of Black-owned businesses reflects persistent inequities in wealth and access to capital. Prior to the coronavirus crisis, the United States was home to just 2.5 million Black-owned businesses, less than 5 percent of which had employees.15 The 114,400 Black-owned employer firms constituted less than 2 percent of the more than 5.7 million American small businesses with employees.16 Research suggests that even when Black-owned firms do get off the ground, they are often smaller, younger, and less profitable. Even highly rated businesses in Black neighborhoods experience annual revenue losses as high as $3.9 billion when compared with similar businesses in non-Black neighborhoods.17

The American small business environment is even less equitable for Black women. Black women own just 41,250 small businesses with employees—less than 1 percent of all American employer firms.18 By contrast, white men own approximately 2,875,251 small businesses with employees.19 These disparities are not driven by individual deficiencies but by the compounded effects of structural racism and racial and gender discrimination that have severely limited access to wealth and capital. For example, 66 percent of Black women-owned employer firms reported that credit availability or funds for expansion were their greatest business financial challenges.20 In response to these challenges, 83 percent of Black women-owned businesses had to depend on personal funds, and 51 percent made late payments.21 Overall, in 2016, only 6 percent of Black women-owned employer firms obtained external financing, and 41 percent of those who did not apply for credit reported that they felt discouraged about credit opportunities.22 As a result, businesses owned by Black women are often smaller and start with no capital or with only personal or family savings.23

Fostering the development of Black-owned businesses will not solve racial inequality, yet it remains an admirable and just policy goal. Once established, these firms have potential to increase wealth, create jobs, and reduce persistent shortages of essential goods and services in Black neighborhoods, including health care, child care, and food. However, creating an environment where people of color—especially Black people—can start, grow, and expand their own businesses will require more than entrepreneurship seminars. The federal government must devote substantial resources toward increasing wealth and access to capital for all Black Americans. The MBDA is well positioned to lead the federal government’s efforts to eliminate racial disparities in business ownership.

An overview of the MBDA

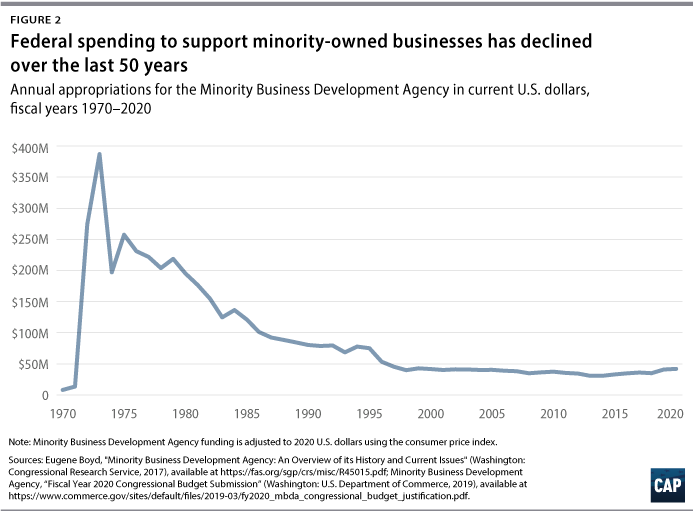

The Minority Business Development Agency began more than 50 years ago as the Nixon administration’s Office of Minority Business Enterprises (OMBE).24 President Richard Nixon created this office as part of his “Black Capitalism” political strategy, which promoted the idea that more entrepreneurial behavior among people of color would promote economic opportunity and equality.25 However, the OMBE was just that: a political strategy that was largely symbolic, with no real authority, dedicated budget, or power to expand access to wealth and capital. Over the following years, the OMBE was moved to the U.S. Department of Commerce, transformed into a federal agency charged with fostering the establishment and growth of minority-owned businesses, and renamed the Minority Business Development Agency.26 Today, the small agency pursues its mission through policy, research, and public and private sector programming.27 While the MBDA does not directly fund small businesses, its network of 44 business centers renders management and technical assistance and helps clients secure contracts and capital.28 Despite its largely symbolic origins, the MBDA remains the only federal agency that exists solely to improve the economic well-being of people of color.

While the MBDA has existed for more than 50 years, Congress has never passed authorizing legislation for this agency, and the agency’s meager funding limits its effectiveness. In FY 2020, the MBDA had just $42 million in total available funds, constituting approximately 0.003 percent of total discretionary spending.29 In other words, for every $1,000 the federal government spent in 2020, it allocated just three cents to foster, promote, and develop minority-owned businesses nationwide. As a result, the agency’s programs are largely limited to providing fee-for-service technical assistance, consultation, and other services to mostly medium- and large-sized firms as well as business workshops and networking services for aspiring entrepreneurs.30 The MBDA’s narrow activities do not include creating the conditions for economic growth and opportunity in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color, such as increased wealth at the household and community levels and greater access to capital. However, a significant expansion of MBDA resources would allow the agency to engage in a variety of activities to meaningfully reduce racial disparities in wealth, economic mobility, and business development over the coming years.

Pursuant to broad appropriations language, the MBDA’s authority derives from executive orders and is reflective of report language from congressional appropriations subcommittees as well.31 As authorizing legislation is not necessary if there is appropriations authority for a particular activity, a new administration could substantially restructure the agency’s mission, authority, and/or programming as long as it is consistent with the appropriations language and there is sufficient funding to support the proposed programs. In FY 2020, Congress passed the following language appropriating funds for the MBDA:

For necessary expenses of the Department of Commerce in fostering, promoting, and developing minority business enterprises, including expenses of grants, contracts, and other agreements with public or private organizations, $42,000,000, of which not more than $15,500,000 shall be available for overhead expenses, including salaries and expenses, rent, utilities, and information technology services.32

Based on this language, the next administration could conceivably authorize the MBDA to provide grants to municipalities for capital investments in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color or even guarantee loans (under “other agreements”) for companies to invest directly in minority-owned business. If Congress provided the appropriations in recognition that these new programs would help the MBDA fulfill its broader mission, there would not be any legal issues. Congress must pass an annual appropriations bill for Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies which often amounts to more than $70 billion. Including a significant increase in the MBDA’s funding in this bill should not make or break its passage.33

5 ideas for revamping the MBDA

The next administration should set forth a blueprint for a more robust and effective Minority Business Development Agency and also demand from Congress the necessary resources for adequate funding. While this could take multiple forms, this section outlines five ideas for revamping the MBDA. The ideas outlined below are based on an assumption that Congress would allocate $4 billion for the MBDA in FY 2022 as part of a comprehensive economic stimulus and recovery plan followed by an annual funding match with the SBA, which was appropriated $1.2 billion in FY 2020.34

1. Initiate an economic equity grant program to foster wealth, opportunity and minority business development in Black, Indigenous, and other communities

Direct capital infusion is one of the most efficient and effective means of building wealth. But Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color have largely been shut out of these programs for decades. As envisioned, a new economic equity grant (EEG) program would allow the MBDA to provide municipalities with up to $50 million per year for capital investments, provided that they not cover more than 50 percent of the total costs of the project(s) funded.

When applying for these competitive grants, municipalities would have to include concrete plans and robust estimates for how they would improve economic well-being in Black and other communities of color. For example, a proposal to renovate and redistribute vacant and abandoned homes—modeled after banking law professor Mehrsa Baradaran’s blueprint for a 21st Century Homestead Act—would have to focus its efforts in predominantly Brown and/or Black communities or communities experiencing high levels of poverty combined with a legacy of redlining.35 The proposals would also have to prioritize minority-owned contracting businesses to carry out renovations; redistribute these homes to long-standing residents of that community; and protect against predatory business practices and gentrification.

EEG program participants would also have to collect and publish racially disaggregated data on wealth and business development. Further, the proposed EEG program would involve strict and independent oversight of municipal projects and regular audits to ensure goals are met. Municipalities that meet or exceed agreed-upon goals could receive additional second-round funding while those that fall short of the agreed-upon goals would face increased scrutiny when applying for additional funding.

Anticipated FY 2022 budget: $1.8 billion

2. Launch an MSI business center initiative within the MBDA

The MBDA’s minority-serving institution business center initiative would make grants available for historically Black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, and other MSIs to operate business incubators and accelerators for minority-owned businesses. As insufficient startup capital is one of the largest barriers to entry for aspiring entrepreneurs of color—especially Black entrepreneurs—a substantial portion of the grant funding would be reserved for direct capital investment in new businesses. These business centers would also offer free legal, accounting, human resources, information technology, marketing, and other services.

While all of the almost 800 MSIs in the United States would be eligible for funding, the competitive process for obtaining grants would consider the demographics of the surrounding area, the institution’s mission, and the institution’s demonstrated interest and ability to support students of color and people of color from the broader community.36 Recipient institutions would receive a minimum of $750,000 per year, but the size of these grants would be based on the range of services provided and the anticipated number of entrepreneurs served. While firms would not have to cede a portion of their ownership stake to the MSI or pay for its services and capital, they would be required to base their operations in or near the census tract in which they received these services for a predetermined period of time.

The MBDA’s MSI business center initiative would complement rather than duplicate the MBDA’s existing business center activities. For years, the MBDA has issued grants to nonprofit organizations, for-profit firms, state and local governments, colleges and universities, and tribal entities to operate a small network of business centers.37 However, these centers, which receive an annual award of at least $250,000 per year and require a 33 percent operator match, focus their services primarily on medium- to large-sized firms seeking to expand to new markets.38 These services, which firms must pay for, include business consulting, private equity and venture capital opportunities, and facilitating joint ventures and strategic partnerships.39 While there are almost 400 majority-minority counties in the United States, the MBDA currently funds just 35 business centers and nine specialty centers across 38 localities.40 Several states with large Black populations, such as Mississippi, Arkansas, and Virginia, do not have any MBDA business centers. A fully funded MBDA could preserve or even expand this existing program while also launching a complimentary MSI business center initiative.

Anticipated FY 2022 budget: $1.2 billion

3. Create an office of research and evaluation

Modeled after similar offices in other federal agencies, the office of research and evaluation (ORE) would examine barriers to wealth and business development in Black and other communities of color; document federal, state, and local agencies as well as nonprofit and corporate communities engaged in erecting these barriers; and provide technical assistance to other MBDA offices and project participants.41

The ORE’s research activities would include publishing statistics and reports, synthesizing existing analyses, and conducting pilot and demonstration projects that seek to reduce racial disparities in wealth and business development. For example, the ORE could award grants to majority-minority municipalities to fund a debt-free college pilot program and conduct a longitudinal study to determine how such a program affects racial disparities in household wealth and business development. This research would likely include the ability to contract out aspects of the research and evaluation process through partnerships with academics and research organizations. All findings would be disaggregated by race, gender, and geography, among other things wherever possible. The ORE’s research priorities would be guided, in part, by a new national task force on economic inequities housed within the MBDA and consisting of civil rights and labor leaders, policy experts, scholars, and representatives from other federal agencies.

The ORE’s ancillary services for other MBDA offices and projects would include technical assistance and guidance on research methods and data analysis, program evaluation, and the synthesis and dissemination of research findings. This could include the creation of learning communities or communities of practice comprised of cities; organizations; or even actual businesses to share best practices, navigate implementation of promising proposals, or communicate while undertaking an evaluation. Through these activities, the ORE would help build the evidence needed to improve overall economic well-being in Black and other communities of color across the United States.

Anticipated FY 2022 budget: $900 million

4. Institute a minority business investment company program

Modeled after the SBA’s popular Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) program—which provided early-stage capital for companies such as Apple, Intel, FedEx, Costco, and Staples—a minority business investment company (MBIC) program would allow the MBDA to lend to investment funds that it licenses and regulates.42 Under this program, a licensed MBIC would use its own capital, in addition to funds borrowed with an MBDA guarantee, to make equity and debt investments in brown- and Black-owned businesses. For every $1 the fund raises from investors, the MBDA would be able to commit up to $4 of debt, subject to a cap of $250 million. MBICs would have to pay the MBDA a licensing fee and invest 100 percent of total capital in certified minority-owned businesses. MBICs would be restricted to investments in U.S. small businesses, with a portion of funding reserved exclusively for early-stage small businesses, which are small businesses that have never achieved positive cash flow from operations in any fiscal year.

An MBIC program would complement rather than duplicate the SBA’s SBIC program, which has repeatedly failed to secure adequate funding for minority-owned businesses. Housed within the SBA’s Office of Investment and Innovation, the SBIC program made just 52 financings—1.9 percent of all financings—amounting to just $34 million—0.6 percent of the total amount of financings—to Black-owned and -controlled small businesses in FY 2018.43 If SBIC financings had been equitably distributed by race, Black firms would have received an additional $681 million in financings in FY 2018.44 Unlike the SBA, the MBDA has a mission and track record that exhibits an unrivaled understanding of and commitment to the success of minority business enterprises. Permitting the MBDA to license and lend to MBICs would create a dedicated stream of capital and expert guidance for entrepreneurs of color who have long been excluded from mainstream investment systems.

Anticipated FY 2022 budget: $70 million

5. Establish an office of advocacy and intergovernmental affairs

The federal government currently operates a variety of programs designed to support minority businesses. For example, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program aims to remedy discrimination in federally assisted transportation contracting markets, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Minority Programs seeks to increase knowledge of and access to energy-sector business opportunities for underrepresented communities.45 But these programs are decentralized and often operate in silos.46

Housed within the MBDA, the office of advocacy and intergovernmental affairs (OAIA) would serve as the federal government’s coordinating body and independent voice for improving economic well-being and minority business development in Black and other communities of color, with a special emphasis on wealth, access to education and capital, and infrastructure. Specifically, the OAIA would:

- Score the effects of proposed legislation and regulations on racial disparities in wealth and business development

- Advance the economic concerns of Black and other communities of color before Congress, the White House, federal agencies, and state policymakers

- Coordinate all interagency efforts to support minority-owned businesses

The OAIA would have strict personnel requirements designed to prevent industry capture and ensure that all research, educational, and advocacy activities serve the economic interests of people of color.

Anticipated FY 2022 budget: $30 million

Conclusion

The Minority Business Development Agency has tremendous potential to lead the federal government’s efforts to create the conditions for economic growth and opportunity—especially in Black communities. The policy ideas outlined above offer just a sampling of what is possible under a fully revamped MBDA. While these policies on their own would not eliminate racial disparities in wealth or business ownership—or close the racial wealth gap—they have great potential to meaningfully reduce inequality over the coming years. These common-sense proposals would promote economic justice and increase economic returns to many more Black-owned businesses. The time is now to revamp the MBDA. The nation cannot afford to wait.

Connor Maxwell is a former senior policy analyst for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center for American Progress. Darrick Hamilton is the executive director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University and an incoming Henry Cohen professor of economics and urban policy and university professor at The New School. Andre M. Perry is a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution. Danyelle Solomon is the vice president for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Kilolo Kijakazi, Christian Weller, Michael Madowitz, Lily Roberts, Olugbenga Ajilore, Richard Figueroa, and Sam Berger for their thoughtful input and contribution to this issue brief.